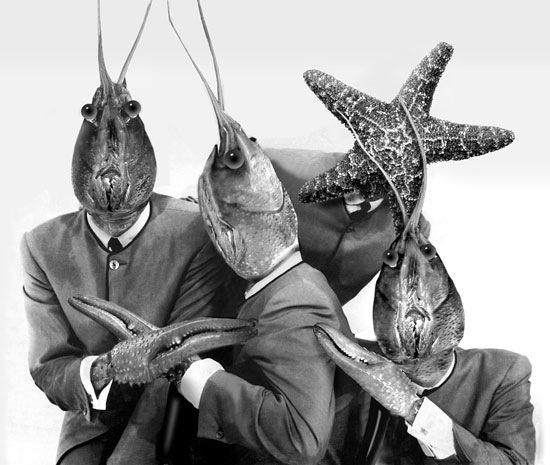

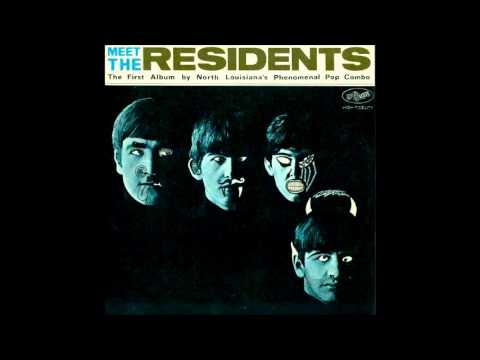

Like many descriptive terms that can be applied to music, ‘weirdness’ is surely a matter of individual relativity, to be discovered in the ear of the beholder so-to-speak. I was probably 19 or 20 and in-between record players, when I asked a friend of mine if he’d mind copying my vinyl copy of Meet The Residents onto a cassette for me so I could listen to it at home. As the opening strains of ‘Boots’ leaked slowly into the room, tinny and remote as if being sung down a length of rusted pipe and accompanied by cacophonous blurts of brass and the plinking of what sounded like toy thumb-pianos, he wrinkled his nose at me as if he’d just sucked on a lime and said: ‘Man, you listen to some seriously weird music.’ Who knew what Nancy Sinatra would have thought of their cover of the Lee Hazelwood penned track, or for that matter, what the Beatles would have made of their unceremonious defacement on the original cover, or their being turned into crawfish on the 1977 reissue? Come to think of it, who were the band behind this monstrous music? It was, to borrow an overused phrase from Winston Churchill: ‘a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.’ As this was still some time before I had heard any of Sun Ra’s music, or even heard the name of Harry Partch, I wasn’t exactly sure what to make of it myself, but I was nevertheless drawn to its uniqueness. It seemed like the original motherlode of otherness to me then and despite hearing many other unusual recordings over the 25 years since that moment, it’s oddness has remained entirely intact.

The story of how The Residents began has long since passed into the realm of legend. According to the myth (perpetuated at various times by the likes of Simpsons creator Matt Groening and British science-fiction author John Shirley), the band met whilst at high-school in Shreveport, Louisiana. They came together as outsiders, sharing an appreciation for J.D. Salinger’s Catcher In The Rye, James Brown’s Live At The Apollo, and the type of dark humour typified by E.C. Comics’ Tales From The Crypt and low-budget horror movies. The five friends split for a time after school but soon found their common interests calling them to regroup. In 1966, they decided to make a break for San Francisco but only made it as far as San Mateo, where their truck broke down. There they stayed for the next few years, working at day jobs and spending their money on crude recording equipment. By 1970, one of the five had left (though there are some who would argue that the fifth Resident was but a playful allusion to the fifth Beatle), and two tapes of proto-Residential material had been completed. When a third tape, which later became entitled The Warner Bros. Album, was returned by Hal Haverstadt, who had been instrumental in signing Captain Beefheart, it was addressed simply: ‘For the attention of residents.’ The friends graciously accepted the name and an identity was born.

It was around this time that The Residents met two individuals who were to have a profound effect on their developing sound. Phillip ‘Snakefinger’ Lithman was a talented, unorthodox British musician who contributed his highly original guitar, violin and piano playing to many of The Residents’ early works. His nickname derived from a photograph taken during a particularly difficult violin solo, during which his little finger appeared to be poised, snakelike and ready to strike. Given the era during which they met in San Francisco, there is also the strong likelihood of LSD being part of the mix. The other figure, N (supposedly Nigel) Senada, was a kind of guru-figure to the group. It has been speculated that his name is most likely a play on the Spanish ‘en se nada,’ which translates as ‘is nothing in’. Most likely he did not exist outside of the imaginations of the band and in retrospect seems to represent the kind of musical philosophising undertaken by Harry Partch. Senada’s ‘Theory of Obscurity’ stated that pure art can only be made without consideration of the outside world. Whilst his ‘Theory of Phonetic Organisation’ involved a decontextualisation of meaning so that the individual sounds of words could regain their primal, magical quality.

In 1972, the band moved to San Francisco and formed Ralph Records, when it became apparent that if they wanted release records they would have to do it themselves. The name came from the slang term for vomiting (‘calling up Ralph on the big white telephone’) and the band named their studio El Ralpho in tribute to Sun Ra, who had called his El Saturn. Most of 1973 was spent recording their first ‘proper’ album Meet The Residents, which was released on April Fool’s Day in 1974 to an utterly indifferent public. Despite giving away free promotional flexi-discs, a mere 40 or so people bought the album in the first year of its release. Given the musical climate of the time, this was hardly surprising. The album defied categorisation and was, in all likelihood, more extreme and experimental than anything the general public would have been exposed to at the time. Given the benefit of hindsight, however, it is possible to identify a number of recordings released some years prior to the album which in all likelihood exerted a strong influence upon its makers. Harry Partch’s stage play, Delusion Of The Fury, premiered at the UCLA Playhouse on January 9 1969, where it was recorded for release on Columbia Records. Inspired by Japanese Noh theatre and featuring a large number of Partch’s custom-made instruments, Delusion Of The Fury fuses tragedy and farce into a unified work in a way that recalls the ancient Greek tradition of following a tragedy with a satyr play and it has been suggested that Partch, who experienced injustice and rejection from society, may have viewed it as a way of expressing and confronting his own anger towards the world. Harry Partch (born June 24 1901) was an American composer, theorist and designer and builder of musical instruments who spent his early years as a transient worker and sometime hobo who rode the railways during the Great Depression, following the fruit harvests across the country. Partch enrolled in the University of Southern California’s School of Music in 1920 but left by the summer of 1922, disenchanted with his teachers and eventually rejecting the validity of the standard twelve-tone equal temperament of Western concert music in favour of a system of just intonation derived from the natural Harmonic series. In order to play his music, Partch devised a number of unique instruments with remarkable names such as the Quadrangularis Reversum (a kind of oversized marimba), Cloud Chamber Bowls, the Chromelodeon and the Zymo-Xyl – an oak-block xylophone augmented by tuned liquor bottles, Ford hubcaps and an aluminum ketchup bottle. Whether Nigel Senada was in fact a cryptic reference to Harry Partch or not, there can be little doubt that he was a strong early influence on the band. The stylistic similarity between The Residents’ ‘Six Things To A Cycle’ (which featured on their 1977 album, Fingerprince), and Partch’s Delusion Of The Fury, is simply too strong to discount. Similarly, a direct reference to Partch’s passing is made in the song ‘Death in Barstow,’ also from that album.

Two other records that are likely to have been an influence on the early Residents’ sound are The Heliocentric Worlds (1965) and Atlantis (1969) by Sun Ra. Already so far ahead of his time as to appear as though he were manifesting from another universe, Sun Ra really pulled out the stops for these two records, which made radical departures from any previous ideas of melody and harmony to produce an otherworldly sound seemingly without reference to anything outside of themselves. Whilst Heliocentric Worlds relies on a heavily percussive sound not dissimilar to Partch’s Delusion Of The Fury, Atlantis is particularly reliant on the unusual sound of the Hohner Clavinet for its evocation of alien textures and tonalities. In John F. Szwed’s excellent book on Sun Ra, Space Is The Place, Ra expresses his interest in music that has unusual tunings, explaining that whilst any group of talented musicians can play a tune together, if they are willing to explore being ‘out of tune’ together, then that is a truly fertile ground for creativity. In this aspect, Ra resembles Partch’s experimentation with microtonal music. Whilst these records existed under most people’s radar, the genius of Meet The Residents lay in its repackaging of some of those ideas as ‘pop’ music. Announcing itself as ‘The first album by North Louisiana’s phenomenal pop combo,’ the album juxtaposes avant-garde elements alongside snippets of pop culture from sources such as vaudeville, early rock and roll and world music.

The album’s tracks run together like the outcome of a game of exquisite corpse, the terrifying opening interpretation of Lee Hazlewood’s ‘These Boots Are Made For Walking’ segueing swiftly into ‘Numb Erone’, a simple piano melody hammered out like an obsessive’s mantra. An eerie horn joins the repetitious tinkle of keys as it in turn becomes ‘Guylum Bardot’ – its creepy melody augmented by nasally intoned lyrics: ‘The love that we’ve been through/Was splintered and sent to/The end of/The rainbow today/Now that its over/The grass and the clover/Grow over/The ground where I lay.’ ‘Breath and Length’ takes the deeply resonating residue left over from the previous track and transforms it into a near industrial cacophony of wild electronic oscillation, dog barks, bell chimes and female voices repeating its insistent refrain. ‘Consuelo’s Departure’ hints at the skeletal ‘melody’ to follow in the next track, with lurching, misfiring swathes of industrial noise, some kind of unidentifiable muted horn sound and tinkling of perhaps a glockenspiel, or keyboard equivalent, before dissolving into the scrabbling and trilling oscillations and screeching guitar of ‘Smelly Tongues’ itself. The nonsensical lyric of ‘smelly tongues looked just as they felt’ takes up unwanted residence in the listeners’ head like the kind of neurolinguistic misfire of some unspecified state of mental aberration. Following that, ‘Rest Aria’ opts for a moment of beauteous respite, a lovely piano melody, punctuated by glockenspiel and abetted by a glorious chorus of otherworldly horns. It is like a minimalist work in miniature, undoubtedly one of the album’s strongest tracks and was apparently used in a Levi’s jeans advertisement that featured a herd of running buffalo. ‘Skratz’ returns to more disturbing territory, a slow mangling of a melody being stretched and chewed up in between gears, accompanied by the unsettling lament: ‘Scratz, scratz, scratz, scratz/(Dirty fingernails)/The sheets still showed the yellow spot.’ ‘Spotted Pinto Bean’ continues the mangling of popular musical forms, nonsensical verbal juxtapositions, operatic singing, a snatch of 1920s big band stylings and the sound of a crowd roaring or perhaps even a train pulling out of a station. ‘Infant Tango’ goes for a kind of cubist, cave-man funk, more squalling horns and a totally infectious piano reprise at its end. ‘Seasoned Greetings’ evokes some nostalgic era long since past, its middle section turning into a kind of krautrock-style piano and guitar jam overlaid with disconcertingly spiky horns, before returning to the evocation of heartfelt family remembrance: ‘merry Christmas ma, merry Christmas dad, merry Christmas sis… I love you.’ As if to refute that sentiment, the final track takes up, with its absurdly nasal vocal: ‘Well, it’s Christmas, but there ain’t nobody raising much of a fuss…’ Then the whole thing disintegrates into utter chaos before becoming caught up in a loop from the Human Beinz’ ‘Nobody But Me,’ which itself soon falls apart, transversing through Harry Partch-esque percussive madness and finally, what sounds like some fading hymn singing: ‘Go home America/Fifty-five’ll do.’

Mummies photograph copyright The Residents

Although it was rumoured that at least one of the Beatles bought a copy of the album after being intrigued by its cover, due to complaints from their record label the 1977 reissue chose to reference the fab four in a slightly less direct manner, this time depicting them as crawfish, as well as one ‘Ringo Starfish.’ Two versions of the album exist – the unedited, mono original 1974 version and the stereo 1977 pressing, which runs around seven minutes shorter. Undeterred by the lack of public or critical response, The Residents continued to work on their film Whatever Happened To Vileness Fats and recorded the ultimate extension of the ‘Theory Of Obscurity’, an album which was not intended for release, entitled Not Available. 1976 saw the abandonment of the Vileness Fats project due to the unsatisfactory nature of the black-and-white videotape they had chosen as a medium, but it also saw the creation of the Cryptic Corporation. A larger premises was acquired at 444 Grove Street and the first Ralph Records mail order catalogue was produced. Over the next few years, The Residents released a number of seminal recordings and finally began to receive positive critical attention as the new-wave scene took off. In 1976, an apocalyptic version of the Rolling Stones’ ‘Satisfaction’ was released as a limited edition of 200. A powerful and disturbing distillation of the music of ‘The Third Reich ‘N Roll’, the single pre-empted punk and sold extremely well when it was rereleased two years later. It became the best selling Residents record of its time, supposedly bringing in a revenue of some $20,000. The English music press began to take notice. John Peel became a convert, as did music critics Jon Savage and Andy Gill. 1978 saw the release of Duck Stab to critical acclaim and the formation of the first Residents fan club, W.E.I.R.D. Snakefinger recorded his first single for Ralph, an ode to paranoia entitled ‘The Spot’, which was released on attractive, translucent blue vinyl and officially became the company’s first non-Residential release. In September 1978, The Residents embarked upon their greatest publicity stunt to date. Having been hard at work on a concept album about ‘Eskimo’ life, the band were suddenly reported missing by the Cryptic Corporation. Feeling pressurised by the Cryptics for the finished product, the band supposedly fled to London with the master tapes. Ralph records responded by releasing Not Available, and the rift was eventually repaired by the mediation of Chris Cutler, drummer with English avant-rock group Henry Cow. The publicity scam worked. After three years of demanding studio work, Eskimo was eventually released in October 1979 and went on to sell 100,000 copies. Fuelled by this success, Ralph records went on to sign a number of other artists, including Tuxedomoon, Chrome and Yello. By 1980, the promotional video was beginning to come into its own and a number of highly inventive videos were directed by Graeme Whifler, who had worked on Vileness Fats. The best of these, the four One Minute Movies, were shot to promote the Commercial Album and were originally aired on MTV when the channel first began broadcasting.

Throughout all of this, the band have strived to keep their identities a secret, employing all manner of conceptual subterfuge and sleight of hand to misdirect attention away from any singular version of the truth. When discussing conceptual art in the realm of pop music, people always talk about the KLF, but it’s worth pointing out that Bill Drummond would have been a young man of 21 when Meet The Residents was released. They were also much further ahead of the curve than conceptual artists such as Jamie Shovlin, who in 2006 staged an exhibition based on the non-existent German glam rock band ‘Lustfaust’. The most famous image that the band produced was undoubtedly the eyeball heads worn with top hats and walking canes that first appeared on the cover of 1979s Eskimo. It’s an enduring image that still tends to crop up from time to time. Only last year, the American singer-songwriter Kesha drew some angry comments from the band’s representatives for using the image without permission when she was joined during her live show by back up dancers bedecked in eyeball masks, top hats and tails. Many people still believe that core nexus of The Residents is comprised of their so-called management company, the Cryptic Corporation, who were established by Homer Flynn, Hardy Fox, Jay Clem and John Kennedy in 1976 when Kennedy came into an inheritance. Homer Flynn has since come clean as the artistic director behind the band but continues to deny any direct musical involvement. I was lucky enough to meet Hardy Fox in San Francisco in 2002 when The Residents played a special Halloween show of their album Demons Dance Alone. It felt particularly odd because I was wearing a mask and he wasn’t. I said to him: ‘Hi, I’ve come over from London to see the show with my girlfriend, which one are you?’ He looked at me a little suspiciously until I explained that I meant which one, as in Hardy or Homer? When the show began and all the band members were on the stage, I recall he was still watching from the wings. Since then, the band have supposedly let their masks drop again, coming out as ‘Randy, Chuck and Bob,’ but it seems clear that this is just another layer in their conceptual strata, similar to the way in which they hired actors to appear ‘unmasked’ on the cover of 1985s The Big Bubble. Whatever their true identities, The Residents have continued to carve out their own peculiar niche at the periphery of popular culture for the past 45 odd years. It is likely that a forthcoming documentary about the band, entitled Theory Of Obscurity will raise many more questions than it answers.