Masta Ace may be hip hop’s greatest ‘what if’ story. Despite being widely recognised as one of the most creative and versatile MCs, his career has been repeatedly derailed by label politics, fickle trends, and cruel timing.

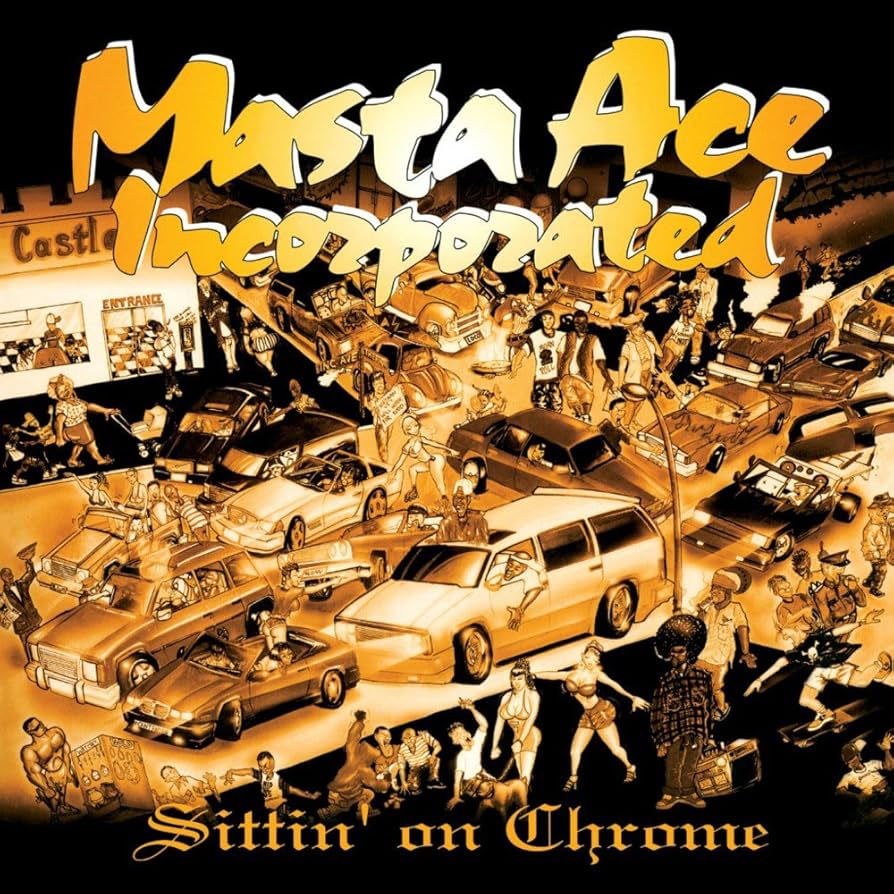

On the release of 1995’s Sittin’ On Chrome, his third LP, he found himself at a critical juncture, as it clearly represented the rapper’s straightest path to mainstream recognition. Ace’s label had pressed him to create an album-length extension of his surprise hit ‘Born To Roll’. What he delivered instead was something far more nuanced: a concept album that bridged East and West Coast sounds just as the rivalry between them intensified. Its mix of bass-heavy bangers and radio-friendly singles captured Ace at his most accessible… but it would also be the last people heard from him for years.

Like much of Ace’s career, Sittin’ On Chrome almost never happened. The Brooklyn MC’s journey began at a roller rink in Queens called United Skates of America. As a broke marketing student in the mid-80s, Ace entered a rap contest with his eye on the $500 runner-up prize. Instead, he won first place and six hours of studio time with Marley Marl – who would soon become one of hip hop’s most important producers. But it took a year of Ace calling his family home before Marley’s sister felt sorry for the novice rapper and gave him the right number. Even when he got to the studio, it felt like he was being brushed off.

He was shunted off into a side room with MC Shan to practice drum programming – a ploy, he suspected, to eat up the allotted time. Yet as the clock ran down, Marley Marl overheard enough of Ace’s rapping to earn him repeated callbacks. Two of his early demos were included on Marl’s debut album, 1988’s In Control Vol. 1, a Cold Chillin’ release that served as a showcase for the legendary Juice Crew: Biz Markie, Big Daddy Kane, Kool G Rap, Roxanne Shante, and Craig G, all rising stars in rap’s golden era. But Ace’s big chance came on the album’s final track, ‘The Symphony’ – a landmark recording that, again, nearly didn’t happen.

After a photoshoot for the cover of In Control Vol. 1, Marley convened Kane, G Rap and Craig G at his studio to record a posse cut. He introduced Ace – complete with nerdy glasses – as his new artist, proposing that he go first. Sceptical looks were exchanged. Kane pulled Marley aside and whispered, “Look, I ain’t fuckin’ with ‘Glasses’. I’m goin’ to the pizza shop and I’m out.” Yet something (no one can quite remember what) kept them there long enough to hear Ace drop his verse. The rest is hip hop history. Decades later, Big Daddy Kane would unequivocally name Ace “one of the dopest MCs ever.”

The release of ‘The Symphony’ marked Ace’s arrival. Cold Chillin’ released his own debut album Take A Look Around in 1990. On the surface, he’d landed in an ideal scenario: part of an electrifying roster on a label pumping out hits with the backing of Warner Bros. The reality was messier. Cold Chillin’ was rife with dysfunction, its artists struggling to get by while their creative primes were wasted in label limbo.

One particular point of contention would have lasting repercussions for Ace. Label executives issued an ultimatum: accept their choice for the lead single or risk having no singles at all. The track in question was ‘Me And The Biz’, an ill-fated collaboration with Biz Markie. Ace had laid down Biz’s parts himself as a placeholder, but the strained relationship between Biz and producer Marley Marl got in the way. Marley convinced Ace to retain his Biz impersonation, and a music video was filmed featuring a puppet in Biz’s place. The label’s blatant attempt to capitalise on Biz’s popularity clashed with Ace’s intuition. The song didn’t reflect the album – a stylistic bridge between the bragadocio of 80s hip hop and the burgeoning social awareness of the 90s – and Ace feared it would make him look like a novelty act. The puppet didn’t go down well in places like Brownsville, where Ace was from, and his credibility took a hit.

As Ace finished his second album, Warner Bros. sent Cold Chillin’ a list that split its roster into two groups. Those above the line could be kept; those below were expendable. No negotiations, no second chances. Masta Ace’s name led the bottom half, followed by the Genius (years before his rise with Wu-Tang Clan). Ace couldn’t believe that he’d bent to the label’s will only to be discarded. They offered to release his second album on Prism, a singles imprint, but Ace had had enough. It was time for reinvention instead.

By 1993, hip hop was transforming. A new wave of artists embraced flows that floated around the beat, threatening to cast rap’s pioneers as relics belonging to an old school. Determined to distance himself from the Cold Chillin’ era, Ace rebranded as Masta Ace Incorporated, expanding to a group comprising Paula Perry, Lord Digga, Eyce, and Uneek – a calculated move to broaden his appeal. If a listener didn’t connect with him, maybe they’d gravitate to another member of the crew instead.

At the same time, he resolved to make the hardest, darkest, grittiest record possible – the antithesis of what Warner Bros. would ever want. The prevailing industry trend, however, was to sign up N.W.A. copycats. Ace didn’t smoke, drink, or wield weapons – and he certainly wouldn’t pretend to. It disgusted him that “hardcore” had become synonymous with gangster posturing, making him somehow less viable as an artist. His response was characteristically subversive: SlaughtaHouse, a 1993 parody album released on Delicious Vinyl. It juxtaposed biting caricature – the title track opens with the fictitious MC Negro and The Ignorant MC touting their platinum-selling LP Shit’s Real Killin’ Motherfuckers Dead – with pointed social commentary on the senselessness of violence.

SlaughtaHouse is now considered a cult classic, but few grasped the satire at the time. Nothing illustrates this disconnect better than when Ace attended a car show in St. Louis and witnessed a wet T-shirt contest soundtracked by the title track; the crowd throwing their hands in the air to the refrain, “Murda murda murda, kill kill kill!”

What no one could have predicted was how a B-side from that album would yield the biggest hit of Ace’s career. Browsing a record store’s bargain bin, he found a Def Jam 12-inch from 1986 by Original Concept featuring ‘Knowledge Me’. Ace used its distorted bassline to forge production alchemy: he re-did the vocals from ‘Jeep Ass Niguh’ on SlaughtaHouse, layering them over thumping 808 beats, the synth line from Madonna’s ‘Justify My Love’, cascading keys from ‘Strollin’ by funk group Mass Production, and the chirping Granny character from The Ohio Players’ ‘Funky Worm’. Finally, he crafted a new hook by repurposing a line from Jungle Brothers’ ‘Done by the Forces of Nature’: “I was born to roll.”

This was more than a remix – Ace had created something timeless. When he told the label, “I think we’ve got something here,” they didn’t get it. ‘Jeep Ass Niguh’ was in the rearview mirror. He fought to include it as the B-side to ‘SlaughtaHouse’ and the track immediately blew up in the Bay Area, spreading through California, Texas, and across the South and Midwest. Demand surged, but record store staff were often oblivious to its existence as a B-side. The label scrambled to catch up, and despite a six-month delay between the grassroots explosion and its official release, ‘Born To Roll’ still reached #23 on the Billboard Hot 100.

Sensing an opportunity, Delicious Vinyl urged Ace to turn ‘Born To Roll’ into an album targeting the same audience. Ace had collected countless books and magazines on car culture, making him a true aficionado. ‘Jeep Ass Niguh’ had been inspired by a love of driving through Brooklyn in his Chevy Blazer, making heads turn with his custom speakers at every red light. Given the label’s commercial track record with Tone Loc and Young MC, Ace agreed to the idea – but only on his terms.

The concept? A fictional cousin from L.A. would visit him in Brooklyn for the summer, creating a cultural exchange that paired the East Coast’s boom-bap beats and jazzy double-bass sound with the sun-dappled bounce of West Coast G-funk – a fusion Ace called “Brooklyn Bass Music”.

Hip hop’s fluid state made directional choices like this inherently risky. SlaughtaHouse was already finished when Dr. Dre’s The Chronic appeared in December 1992, making Ace feel like his grimy satire sounded instantly outdated. The Chronic redefined hip hop’s sonic possibilities. Loud, smooth and meticulously EQ’d, it also recalibrated the benchmark for mainstream success. Analysing what made it so effective, Ace was struck by seemingly effortless flows like: “One, two, three and to the four / Snoop Doggy Dogg and Dr. Dre is at the door.”

Ace is a natural storyteller with unique phrasing – ‘Born To Roll’ is the only hip hop hit you’ll find with “centrifugal” in the lyrics. He’s also consistently motivated by being overlooked, by feeling he has something to prove. Sittin’ On Chrome, then, presented an opportunity to both give Delicious Vinyl the hit album they wanted and to challenge himself creatively.

Right from the start, with the sound of a car door slamming on ‘Intro’, Sittin’ On Chrome has the feel of a movie. Ace quickly sets up the story: two wildly different cousins spend three and a half months together, chasing a good time despite their differences. A split-second snippet from ‘Gimme Some More’ by The J.B.’s gets stretched until it sounds like a gospel choir sustaining one long note, while a muted trumpet and gentle piano help build the atmosphere. At a time when rap albums were notorious for frivolous skits, this epitomises what writer Mark Slutsky calls “good-handedness” – an immediate sense that the creator knows what they’re doing.

‘The I.N.C. Ride’ is Masta Ace Incorporated at its catchiest, even including a Snoop-like flourish: “R, I, D to the E / check out how we, the I.N.C.” The original version was a jazzy, downbeat track produced by Louie Vega, but when the label recognised its commercial potential, it was bumped to a bonus track. Ace remixed it by combining the groove of Leon Haywood’s ‘I Want’a Do Something Freaky To You’ with the Isley Brothers’ ‘For The Love Of You’, adding a heavy hit of synths for extra swing.

Sittin’ On Chrome saw the I.N.C. solidify into two men and two women, each with a distinct style. Lord Digga and Paula Perry provided distinct shades of hardcore: one blending bravado with flecks of off-beat humour, the other raw and confrontational. R&B singer Leschea added a gentle touch with melodic hooks and warm harmonies, earning her own track with ‘Turn It Up’. All played off Ace’s narrative precision. It’s easy to overlook the intricate layers of slant rhymes, internal rhymes, and compound rhymes that weave through his verses, showcasing a playful yet technically masterful approach in lines like: “I’m Zsa Zsa Gabor-er/ Hit the floor-er, Aurora Borealis, I’m rockin’ Dallas/ And Houston I’m boostin’, like I was turbo/ I smoke MCs but pass on the herbal/ So do it one time for the Ms in the trunk/ We got the answer, it’s that B bass-drum.”

Even though Ace holds his storytelling prowess back, Sittin’ On Chrome feels perfectly designed for cruising. The music puts listeners in the backseat as the crew explores the city, chasing fleeting encounters with the aimless freedom of summertime drives. Bluez Brothers – a production team of Lord Digga and Norm ‘Witchdoc’ Glover – were fresh off contributing three tracks to Notorious B.I.G.’s Ready To Die. Ace himself had furthered his own production skills with the help of DJ Premier, buying the same setup (an Akai MPC60 and S950 sampler) to study directly from the master. The first track he created with his new tools was the slinking ‘4 Da Mind’. Combined with the grinding basslines behind ‘Eastbound’, ‘The B-Side’ and ‘Da Answer’ (a masterclass in sampling wizardry), there is undeniable magic here despite the need for a tighter edit.

Sittin’ On Chrome came painfully close to achieving its goal. ‘The I.N.C. Ride’ earned the most radio play of Ace’s career when the label had to renegotiate its distribution, forcing units to be pulled from shelves and killing momentum. Ace had fulfilled his end of the bargain by making a more accessible album, but he felt the label failed to hold up its side.

What made things worse was that people didn’t understand Sittin’ On Chrome’s underlying theme. Rather than easing tensions, the coastal rivalry only deepened. Many mistook Ace as taking a side – the side he wasn’t from. Since his label was in L.A. and the videos for ‘Born To Roll’ and ‘The I.N.C. Ride’ were shot there, that was enough for some to brand him a West Coast sellout. Back home in New York, people would stop him on the street and ask, “What are you doing here?” – as if to say, “You’re one of them.”

This feeling of his hometown turning its back on him played a part in Ace’s decision to sign with Atlantic’s Big Beat label. He spent two years making a new album when, in 1998, they asked him to chase the R&B-leaning, chart-dominating sound of Bad Boy Records instead. Ace refused; the project was cancelled.

In the meantime, the I.N.C. crew dissolved amid solo ambitions and tension over production deals. Paula Perry’s debut album Tales From Fort Knox got trapped in record label turmoil: signed to Polygram’s Loose Cannon Records, it then shifted to Mercury before finally landing at Motown’s hip hop subsidiary Mad Sounds – only to be shelved until its release 26 years later, in 2022. Leschea signed with Warner Bros. and released Rhythm & Beats in 1997, but it fell through the promotional cracks and remains her only album. Finally, Lord Digga’s own deal with Big Beat also didn’t lead to an album release; his first real full-length (Snapped) only emerged in 2024.

Ace went through a dark time after being dropped. He began shopping beats around, submitting his CV to record labels, convinced that nobody cared about his music. He was done with it all. In 2000, he hesitantly agreed to a European tour only to be blown away by packed venues where audiences knew every word to his songs. Hip hop politics didn’t seem to matter. People just loved the music.

Around this time, Ace was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis – something he kept secret until 2013. Rather than ending his career, it fuelled him to make a definitive artistic statement while he still could. Witnessing Eminem’s rise – and hearing him acknowledge Masta Ace as a key influence – inspired him to be himself without compromise. There would be no regrets this time.

After a six-year hiatus, Ace returned with Disposable Arts in 2001. It offers a scathing critique of the music industry through a fictional ‘institute’ for hip hop riddled with fake personas, shallow fame, and artistic surrender. The cover art is a wry callback to Sittin’ On Chrome, depicting Masta Ace on a solitary car seat in the street. It came out a month after 9/11 on indie label JCOR Records, which promptly collapsed. Undeterred, Ace pushed forward with a creative resurgence that has produced a series of thematic albums – whether it’s Son of Yvonne, a tribute to his mother set to MF DOOM beats, or The Falling Season, which tells the story of his school years – that honour rap as art, not a product.

Would all of that have happened without Sittin’ On Chrome? The album’s ultimate significance may lie not in the stardom it narrowly missed but in the lessons it taught and the resilience it fostered. What Masta Ace calls his “compromise album” undoubtedly paved the way for his later creative freedom. It’s a reminder that sometimes the most compelling artists aren’t those with the smoothest trajectories, but those who navigate obstacles without losing their way.