As his post Cleaners From Venus duo The Brotherhood Of Lizards had ended the previous year, 1991 found eternal bridesmaid Martin Newell once again up against the indifference of the music industry. "I’d done all the right things only to find myself a few months down the line with nobody wanting to know me. All my friends were doing alright – Giles Smith (who had played with Newell in The Cleaners From Venus) interviewing Lou Reed in New York, Captain Sensible out in Ibiza, and Nelson (Newell’s partner in The Brotherhood of Lizards) doing stadium gigs with New Model Army – and I’m just digging a ditch for a doctor in the rain thinking, ‘Well, that’s it, if nobody’s interested, I’m just gonna do this.’ So I became a gardener for six months. Which sorted my head out. There was something very pure about it and it created that Zen Gurdjieff/Ouspensky thing, which happens when you humble yourself so much that you’re high on it. You empty all the rubbish out and suddenly you’re pure again and then the songs start coming and then the phone rings."

And the phone did just that. Early one morning in 1992, Martin picked up the receiver to hear Andy Partridge introducing himself and offering to swap XTC’s latest offering, Nonsuch, for Martin’s second book of poetry, Under Milk Float. Today England’s most published living poet was then in the early stages of carving himself out a poetry career. Partridge had read Martin’s first book, I Hank Marvinned, which according to Newell was "just a little sixteen-page glossy pamphlet, but it had all the early rock resonances with poems about Hank Marvin, Deep Purple, and Status Quo’s fourth chord". XTC’s Dave Gregory recalls the title poem as "double-entendre about playing air guitar as a child in front of a mirror but he couched it in a way that it made it seem like he was doing something else, highly personal, in the privacy of his bedroom. Very clever and very funny. And Hank Marvin had inspired all of us to play guitar when we were kids."

Partridge had been vaguely aware of Newell before this. While XTC was making The Big Express in 1984 at Crescent Studios in Bath, Cleaners From Venus drummer Lol Elliott starting hanging around the studio, eventually giving Partridge one of the Cleaners’ homemade cassettes. "In terms of fidelity," Partridge winces, "it couldn’t have been worse if it was recorded on a cylinder through a toilet roll. But the songs were pretty decent." Years later, Partridge would recognise Martin’s name on I Hank Marvinned as "the fella from The Cleaners From Venus".

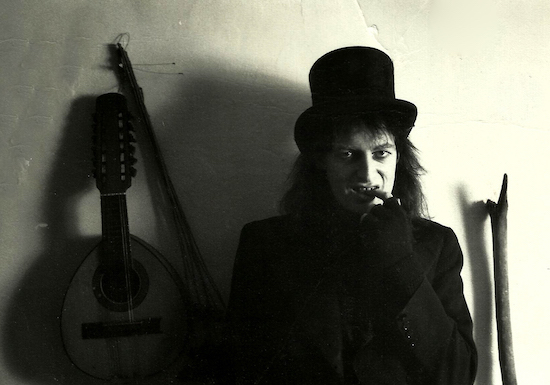

In the summer of 1992, Martin was doing the poetry support slot for a Johnny Moped reunion gig at the old Marquee club on Charing Cross Road in London. Captain Sensible, Kirsty MacColl and Steve Lillywhite were all in attendance. At some point in the evening Martin met Humbug label boss, Kevin Crace, as this group moved from the gig on to the rock & roll Columbia Hotel in Bayswater. At the end of the night Crace, a big fan of The Brotherhood Of Lizards, would say to Martin "come see me Monday morning and there’s a record contract for you". Crace had just left Pinnacle Records to set up his own label and between 1993-1995 would release records by Captain Sensible, Colin Lloyd Tucker, TV Smith, él Records alumni Louis Philippe and Simon Turner, as well as David Devant & His Spirit Wife’s ‘Pimlico’ 7". Crace fondly recalls, "Humbug was a really lovely label, it was like a big family. A beautiful family of real eccentrics that would never be signed to any other label at that time. I wanted this Andy Warhol Factory notion of the right people being around the label at the right time. All the artists regularly worked on each other’s albums. I signed each artist because I had total faith in them. It was also much more about how brilliant you’d look in a top hat than anything else. If you turned up at Humbug in a top hat, you were getting signed on the spot."

"Obviously Martin’s songs were just superbly brilliant. So I suggested to him, ‘If we’re gonna make this work, we should really go straight to the top, and see if we can get Andy Partridge to produce it.’ It just seemed such a natural equation to bring those two people together. I constantly listened to XTC and I thought that Andy Partridge would be the perfect soulmate to Martin for this release. And to me, The Greatest Living Englishman almost sounds like it could be the follow-up to Skylarking."

A phone call was made and Partridge’s interest was piqued. Time was not a problem as XTC had just gone on strike to their record label, Virgin Records. Partridge explains, "The strike was Dave Gregory’s suggestion and initially I thought he was insane but after a couple of days I realised this was a fantastic idea. We had put out Nonsuch, it had been ignored to death, and we weren’t seeing any royalties." Having sent in a team of auditors to Virgin, the accountants discovered missing money and claims were then disputed. The company refused to settle the major ones, which added up to a lot of money, leading XTC to inform their label that until they settled, Virgin wouldn’t be getting any more records from the band. As Newell puts it, "Like all good British workmen, they went on strike. The expression Andy used in his usual elegant way was they were ‘a ship trapped in ice’." (See the later song of this name on Partridge’s Fuzzy Warbles Volume II.)

The first issue, and major component in the sound of The Greatest Living Englishman, was the budget. At the time, Partridge was earning £3000 per song as a producer. A twelve-song album would therefore fetch him £36,000. The money available was less than a third of that, with no room for studio bills or musicians’ fees. Partridge was concerned that if anyone were to hear of his working below his normal pay rate, it would be the end of his production career. But the project intrigued him. "I thought about it and thought if I do this in my garden shed studio – I say studio, it’s twelve by eight, minuscule – but if I did it in there, I could engineer it, I could play what Martin can’t play and he can play what I can’t play. I was sure we could get through somehow. So I thought, ‘Yeah, why not? It’ll be an interesting little exercise to see what quality I could get out of the shed.’ I called Kevin Crace back and said, ‘I’ll do it, but you give me the whole budget and I’ll handle everything – production, engineering, mastering.’ And it was agreed. So I asked Martin to send me some demos of what material he’d like to do."

Wherein came the second hurdle. Newell sent twenty of what he considered to be his best songs, and Partridge replied, "Some of these are really good. I reckon we’ve got half an album here." Newell was aghast. "I was like, ‘Half an album?! This is my best work. Obviously [this is] someone who is not as impressed with my genius as I am.’ [laughs] He said, ‘Can you write some more?’ And I went, ‘Right. I’ll show him.’"

Partridge stands by his original assessment. "Seriously, if I’m going to produce somebody, I can’t do the bullshit thing because it reflects on me. If I don’t think the songs are quite there, I have to say so. And it’s the same template that I follow for myself. I think Martin was a bit shocked at me telling him this. But I started the way I intended to go on which was to be honest with him. What happens is people get fired up when they can hear that you are serious straight off the bat. He wrote some great stuff after that." Martin then dashed off another twelve or thirteen songs, the two chose the best of the lot, and they were ready to roll.

Work began mid-January 1993, with Newell traveling from his home in Essex to record in Swindon, staying with Lol Elliott of Cleaners From Venus in Bath. Outsiders thought a clash of egos would arise between the two maverick musicians but neither man can remember ever once arguing. "I never found him difficult going", Newell recalls. "I thought you’re the producer, I’m the artist, let’s just do this. And I trusted him. He has the hearing of a bat. Things I would’ve just left, he had me go back and do seven, eight, nine times. He was exacting, but he wasn’t cruel. He was fabulous to work with. We got on like a house on fire." Partridge remembers the experience as being "funny and intense. A lot of laughs were had. Which we needed because I was in the early stages of a divorce at the time and Martin was going through something similar. There was a lot of bonding on that front. Every few days we’d go over the pub and commiserate. So we needed lightness and thankfully we both had a similar daft sense of humour. It was a great distraction from real life."

After a break in February/ March for a poetry residency in Middlesborough for Newell, come April the two got on with the album full-time. While revealing that he wrote Wasp Star’s ‘Church Of Women’ as well as songs for Terry Hall during this time, Partridge’s diaries for 1993 are full of him taking his broken ADAT recorder in for repairs and then picking it up again, a cycle that had occurred four times before summer even began. But Friday 18 June is the date that stands out as being when Captain Sensible, hungover from a gig in Bristol the night before, arrived to play the Hendrix-esque, acid-kicking-in solo at the climactic end of ‘The Green-Gold Girl Of The Summer’. Partridge recalls, "He turned my little 30 watt combo [amp] up full and it was so painful, Martin and I had to stand outside the studio, and it was deafening outside. But what he played was exactly what we wanted."

‘The Green-Gold Girl Of The Summer’ was one of the new compositions from Newell’s second batch of songs, as was ‘We’ll Build A House’ which dealt with the homeless situation. Although not often political, there was much happening in the early 90s that got Newell riled up enough to write. The Poll Tax Riots inspired ‘The Jangling Man’. Composed at the time when it seemed like he would be trading his guitar in for gardening gloves, Newell remembers, "The government said, ‘Well we’ve taxed everybody so why don’t we tax the working poor as well?’ I’d never signed on in my life but I was that poor that I was just about making enough money to pay for my own revolution if I brewed my own beer, cycled everywhere, and didn’t eat too much. But if they took another £30 a month off me, which was a substantial amount then, I didn’t know what was gonna happen. It could’ve been like the Edwardian crisis again." ‘A Street Called Prospect’ also dealt with the changing times. "I was looking around at the rundown streets and thinking, ‘It’s not all modern.’ I sang it in a voice like someone giving bad news down the phone. ‘What’s the old neighborhood like?’ ‘Oh it’s really rundown and the pub’s all mired in old men in nostalgia.’"

Newell thought the descending nature of ‘A Street Called Prospect’s chords might bring on comparisons to Ray Davies, but the song "couldn’t not be written". He’s quick to point out his music is less Kinks-y than people think. "Everyone expects that Ray Davies was my biggest influence and he wasn’t. Pete Townsend was much more so, especially around the time of The Who Sell Out. And actually, although I was pretty familiar with the Beach Boys, at the time we were making the record, I’d never heard Pet Sounds. Andy was incredulous when I told him and he immediately made me a cassette copy of it. John Shuttleworth, The Left Banke, and Pet Sounds were my soundtrack while I was making The Greatest Living Englishman. They were too late to influence it, the songs were already written, but that was my recreational music."

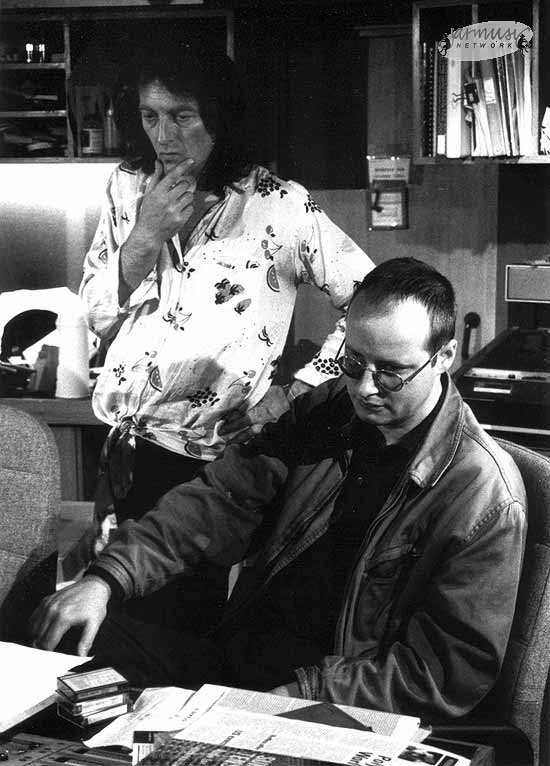

Photograph by Geoff Lawrence

‘She Rings The Changes’ is the album’s big pop number. Newell comments, "It’s just one of those joyous, happy pop songs. I was thinking this is what it would be like if I met someone new. It metamorphosed into this pop beast." When I mention to Dave Gregory that ‘She Rings The Changes’ is ‘a fantastic pop song’, he is quick to reply, "They’re all fantastic pop songs. They were all instantly likeable. This is the great thing, they all had great instant hooks. Martin has a real great gift for melody, along with his poetry and his great lyrics, he always has the brilliant knack of marrying the right melody to a particular turn of phrase. That’s why straight away I thought this is a real discovery." Gregory met Newell during the recording when he would often stop round to see how things were progressing. Newell has an abiding memory of Gregory always arriving with his dripping umbrella and sensible raincoat and the three men then discussing their love of 60s pop over a cup of tea. Gregory’s knowledge of musical minutiae led to a credit of ‘Pop Mastermind’ on The Greatest Living Englishman‘s sleeve.

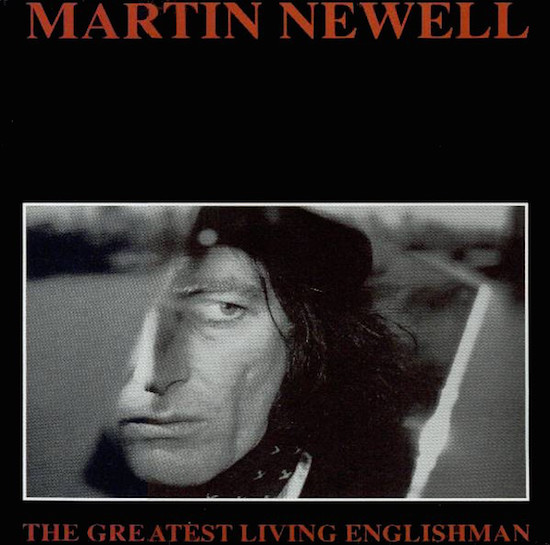

Another credit would be quite contentious. On all initial pressings, the record was billed as ‘Martin Newell Featuring The New & Improved Andy Partridge’. Kevin Crace explains that "by the time we’d finished, it had become obvious that Andy had done so much on this album that he should have some other credit besides ‘producer’". Partridge remembers, "That was a real fuck-up actually. Originally the album was not called The Greatest Living Englishman, it was going to be something like Martin Newell’s Great New Product and we were going to make it like a soap packet. And we thought it’d be fun rather than to say ‘produced by Andy Partridge’, it would contain ‘new & improved Andy Partridge’, like an ingredient. And then suddenly, without me knowing it, the album title changed but for some reason they kept that credit. It made sense when the whole concept was like a soap packet, but then the title changed and it all went out the window."

The song that would eventually give its name to the album title was another from Partridge’s request for more tunes, and one the producer thought "excellent". Despite Martin being concerned that he might be seen as self-aggrandising, ‘The Greatest Living Englishman’ is actually "a tale about one of these 60s whizz kids when the class barriers broke down in the wake of the Beatles and the Profumo scandal. Suddenly it seemed possible that a Lord could be a barrow boy and a barrow boy could be a Lord. Then in the 70s and 80s some of these guys started to come a cropper, they went bankrupt or got sued. The whole thread going through The Greatest Living Englishman is this guy had done something terribly wrong from which he personally suffered but also a load of people lost money, some nuclear subs had been sold off, and somewhere you hear some burnt-out old rock star saying, ‘Oh yeah, and then Steve went mad and Dave died.’ It’s a terrible series of disasters." On album closer, ‘An Englishman’s Home’, Lol Elliott impersonated an old Englishman down on his luck to finish off the story over a quasi-classical, "Essex kitchen table Handel" (Newell), piece.

Elliott would also play drums on ‘A Street Called Prospect’ and ‘The Green-Gold Girl of the Summer’. Due to the confined space in Partridge’s studio, the producer remembers "every time he went for a cymbal I’d have to duck. And I couldn’t lean backwards because I’d slice my skull off." More practical than risking death by percussion was for Partridge to play a Yamaha drum pad on most of the record. Though he still thought real drums sounded better. "Like on ‘Home Counties Boy’, those are small play drums, one of them is a tambourine with all the jingles taped up so they don’t ring. We fancied some English Civil War-style drumming on that track." Newell recalls Partridge making a couple of shakers out of Fairy Liquid bottles and using this, what Partridge called ‘scout hut drum kit’, on ‘Straight To You, Boy’ as well.

‘Straight To You, Boy’ was the last song written for the record with Newell finishing writing it in Partridge’s kitchen while the producer mixed down drums outside in the studio. Another late addition was ‘Goodbye Dreaming Fields’, a song Partridge was very fond of and remembers as "great fun to do". To Martin the song at first seemed like typical Brotherhood of Lizards/Cleaners From Venus-type fare. "I hadn’t realised what I got there. But Andy heard something in it that I didn’t hear and it came out very well."

Speaking of things Andy’s heard that others might not have, second track ‘Before The Hurricane’, with its lovely string samples, contains a secret. "I don’t know if I’ve ever told anyone this before, not even Martin. But ‘Before The Hurricane’ was done as an homage to ‘Secret Love’ by Doris Day. About halfway through ‘Secret Love’, it goes into these horse-trotting, pizzicato strings and I wanted to do something that sounded like that. And I did." The song dates from the year after the 1987 UK hurricane when Newell was writing lyrics for Captain Sensible. "I was at Captain’s house and he had to go give the kids a bath. So I started mucking around on this keyboard and these chords came out. He was gone for a while so I got this idea knocked out, recorded it, and wrote the rest at home. It reminds me of a very breezy early English autumn day, walking down a narrow lane. That romantic timelessness of an English village in autumn."

The album was mastered in August at Porky’s in London over an 18 hour session and released in November bearing the Humbug catalogue number BAH10. Rolling Stone gave it four stars and compared it to The Flamin’ Groovies’ Shake Some Action. US label Pipeline Records got ‘Christmas In Suburbia’ played on some big alternative rock radio stations during the holiday season and the album was well-received in America. It was critically acclaimed in France, and did well in Germany and Japan. Martin would tour these last three countries the following year with an all-star backing band of Dave Gregory, Captain Sensible, Nelson, and Garrie Dreadful (The Damned).

Looking back on the record 25 years later, all involved realise it was something special. For Kevin Crace it is one of the great records of all time as well as the classic Humbug release. "It’s such a positive album when you listen to it. Martin was the real deal. He lived the country life which meant that he would be working in the cold putting up fences and things. It’s a very genuine album." Martin himself is on the fence about it being his best work. "I do listen to the album with a great deal of fondness but I compare it to how a lot of people say that Sgt. Pepper’s is The Beatles best album but many people would say that it isn’t. And getting right close to home, many people would say that Skylarking is XTC’s Sgt. Pepper’s, but it’s certainly not my desert island XTC album. That’d probably be by Dukes of Stratosphear. [laughs] The Greatest Living Englishman is not necessarily my best album but it’s got some good kit on it." Andy Partridge does himself a disservice by agonising over his engineering and mixing, done at the time on an eight-track ADAT and old Mac computer in his shed. But The Greatest Living Englishman producer reflects, "It’s a lovely album. The songs are excellent. I’m proud of it. I just wish that I had all the tracks and the obscure equipment it was recorded on and I could remix it. I could almost get it up to Beatles ’66 level these days." The nature of the virtual instruments used make this impossible, but the nature of the record is what makes it so special to most listeners. Partridge sums this up best, "It is lo-fi, but dammit, it is lo-fi glorious."

The Captured Tracks vinyl reissue of The Greatest Living Englishman is out now