"I think I know a good deal about physical suffering. But this is worst of all, to feel your soul dying. I wonder if it is because tonight my soul has really died that I feel at the moment something like peace."

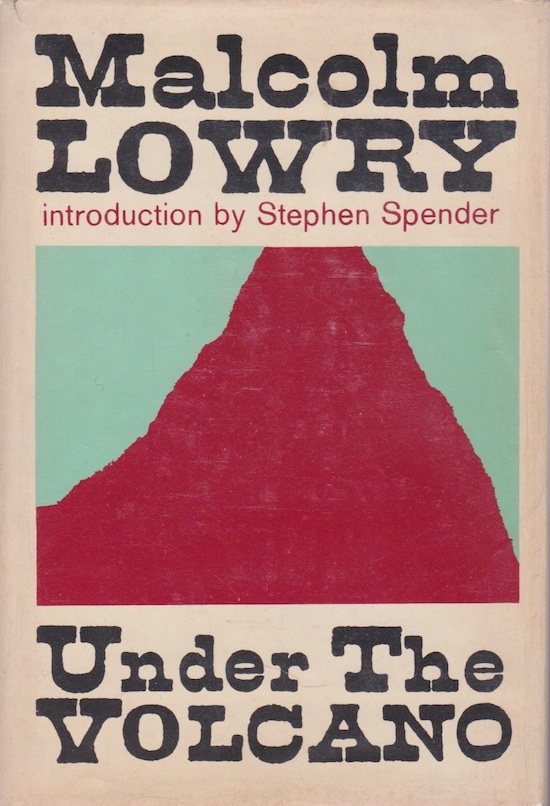

Under The Volcano, Malcolm Lowry’s bible for drunks, pivots on the Day Of The Dead festival in Quauhnahuac, Mexico in 1938. It was during that same year that the pseudonymous Bill W started writing the "Big Book" of Alcoholics Anonymous in Akron, Ohio. Addiction memoirs are a genre in themselves these days, but in 1938 little had been written about substance abuse, and where revelations had been shared in, say, Thomas de Quincey’s Confessions Of An English Opium Eater from 1821, there was never any prospect, or even concept of, "recovery" in its modern sense.

While Lowry started earlier, Charles R Jackson rather beat him to the punch when The Lost Weekend was published in 1944. Lowry was terrified the book had stolen his thunder. It was made into an Oscar-winning film by Billy Wilder the following year, and the title has passed into modern parlance, but perhaps it was the figurative John The Baptist leading the way for the Messiah Of Drunkards. (Incidentally like Jesus and John, Jackson’s and Lowry’s ends were both tragic and came too soon, though unlike the former pair, they were self-inflicted).

The Jackson novel was a bestseller in its day and then ran out of steam, whereas Under The Volcano continues to shift copies, often makes those 100 Greatest Novels Ever lists, and towers over the John Huston movie version like the volcanoes Popocatepetl and Iztaccihuatl in the book (and that’s despite a mighty performance from its lead, Albert Finney).

The novel’s density and its vision are truly something to behold and to get lost in, a big fatalistic forest of fear and confusion and belligerence, full of flashbacks and misadventures and copious bottles of mescal drunk down to the worm. It’s notoriously slow to get going, with a first chapter so vast and detailed that many fall at the first hurdle. A second or third reading are recommended, and Christ knows how difficult it must be to navigate while drunk.

Written as a roman à clef with Lowry as former British consul Geoffrey Firmin – and some more characters besides, including a younger version of himself in Geoffrey’s half brother, Hugh – it’s the first truly great modern addiction memoir. It differs from most recovery memoirs nowadays, however, in that there’s no recovery. From David Carr’s examination of memory and the unreliable narrator in 2008’s The Night Of The Gun, to Amy Liptrot’s wonderful 2016 nature memoir The Outrun, there is usually a message that addiction can be, if not beaten, then tied up in a room somewhere and monitored. In the foreword to the Penguin Modern Classics edition of Under The Volcano, Michael Schmidt notes that "the whole book is a denouement".

In the 1930s there was little hope of respite from then affliction of addiction, and Lowry regarded alcoholic tragedy as his destiny. Had he stayed in New York – where he went for a while ahead of his misadventure in Mexico – then he might have been lucky enough to catch some of the very first meetings for abstinence-based 12 step recovery. Lowry would have understood the first step – "We admitted we were powerless over alcohol – that our lives had become unmanageable" – because he clearly wasn’t in denial about his alcoholism. Rather he embraced it. (Though had he stayed in New York then we wouldn’t have had Under The Volcano).

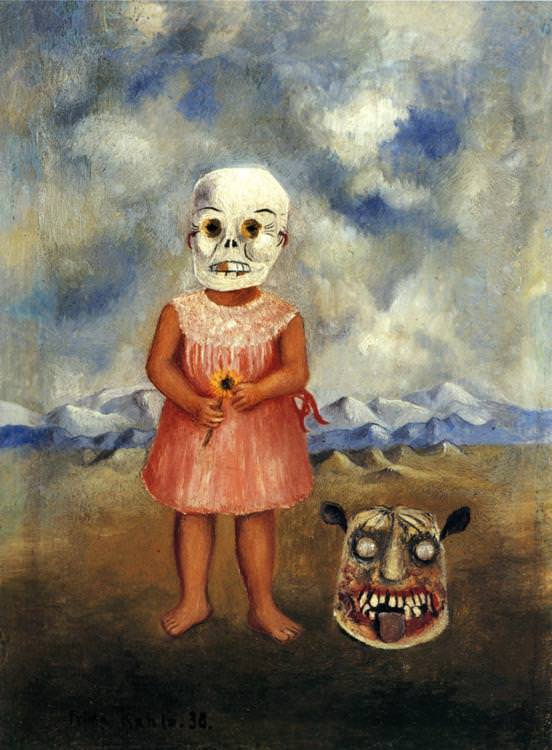

Frida Kahlo’s Girls With Death Mask

Alcoholics Anonymous: The Story of How Many Thousands of Men and Women Have Recovered from Alcoholism, was published in 1939, and as the titular byline suggests, it collects the testimonies of numerous drunks and elaborates on how they maintained sobriety, mostly with the help of a "higher power". With the decline in Christianity and slow acceptance of other faiths, this higher power usually manifests in the conceptual design of the alcoholic’s own choosing these days, though it’s regarded as a spiritual programme whatever your belief system.

Pointedly Lowry has the Consul say, as he drops his stricanine to the ground, "the will of man is unconquerable. Even God cannot conquer it"” Perhaps Lowry, the Petrarchan lover, only believes in "No se puede vivir sin amar" ("you can not live without love").

There’s a chapter called We Agnostics in the Big Book, dedicated to trying to convince non-believers that they are essentially wrong, and true apostates will find little comfort there. If religious adherence is a thorny issue, what the Big Book gets so right is the conviction that only a recovering alcoholic can help another recovering alcoholic. It also insightfully, and almost systematically, identifies the myriad behaviours of problem drinkers to reveal that none of us are quite as special as we might think we are (it’s difficult to imagine Lowry would have countenanced this idea).

The violent, the self-pitying, the functional, the intermediate familial, the chronic severe; Bill W and his friend Dr Bob had them all pegged (even if many of these terms came later). Behavioural patterns that had no name are also identified – and unhelpfully referred to as "defects of character" – though the recognition that alcoholic conduct can wildly vary was massively important to the burgeoning recovery process in the 1930s, and has continued as a cornerstone of recovery ever since.

Go to any AA meeting and you’ll hear strange shibboleths that will become familiar after a time. People talk of "the rooms", the "steps and traditions" and someone called "John Barleycorn". And then there are "dry drunks" and "bellybutton birthdays" and something called "geographicals". The Australian AA website defines a geographical as: "Trying to solve our problems by moving to a new location, an attempt to cure our alcoholism by getting a ‘fresh start’ in a new city. It doesn’t work. There is a saying around AA, ‘Wherever you go, there you are.’ Also known as ‘changing deckchairs on the Titanic.’"

Lowry himself was a drunk prone to upping sticks and attempting to make a life for himself elsewhere. Born in New Brighton in Cheshire to an affluent family in 1909, he was educated at Cambridge, and his early peripatetic adventures included working as a deckhand on a tramp steamer to the Far East. Before all that, as a youth, he was decorated with sporting accolades, including winning a junior golf tournament at the Royal Liverpool Golf Club at 15. As an upper middle class son of a cotton broker he had a maid, a cook and a nanny, but he spent his life feeling neglected by his mother and was apparently tormented at school because of the size of his hands. Lowry was also said to be haunted by the guilt he felt when his roommate at Cambridge committed suicide, after Lowry spurned his advances, and an ill-advised trip to the Syphilis Museum on Paradise Street in Liverpool at the age of five disturbed him for life.

By the age of 25 he’d cut his family off to the extent that he never saw any of them again, though he did still receive money from his father. By this time he was gadding about in London, Paris and parts of Spain, devoting his time to his two obsessions: literature and alcohol. He identified with the poets of the New Apocalyptics movement, especially the more bibulous ones like Dylan Thomas. Recognisable influences on Under The Volcano included Joyce, Melville, Faulkner, Conrad and Eliot.

When he ran into marriage problems with first wife, Jan Gabrial, he went to New York – a city he loved for its "existential fury" – and he eventually checked himself into the Bellevue Psychiatric Hospital in 1936; those experiences are recounted in the novella Lunar Caustic, published in 1968, 11 years after his death. Malcolm and Jan travelled to Mexico in an attempt to give their marriage one more go, and that’s where he started writing Under The Volcano. Jan Gabriel could apparently no longer cope with marriage to an alcoholic manchild who needed a mother more than a lover, and took off with somebody else.

Lowry was apparently locked up three times, once over Christmas, and was deported in 1938 under mysterious circumstances. He then spent some time in another clinic in Los Angeles, paid for by his father. He met his second wife, Margerie Bonner, and they went to Vancouver soon after. It was supposed to be a short trip, but Lowry ended up staying for 14 years. Volcano was submitted to publishers and was rejected by all of them. He continued to rewrite and redraft with the help of Bonner, and the novel was finally published in 1947 to some acclaim. Problems with classification no doubt put many publishers off, though one imagines endless redrafts only rendered it more labyrinthine and strewn with arcane symbolism.

"It can be regarded as a kind of symphony," said Lowry of his own work, "or in another way as a kind of opera – or even a horse opera. It is hot music, a poem, a song, a tragedy, a comedy, a farce and so forth."

Few books capture the melancholy and excitement and the regret that the drunk experiences. It’s full of prose too that plays to the gallery of inveterate drinkers. The beautiful absurdity of a line like: "How, unless you drink as I do, could you hope to understand the beauty of an old Indian woman playing dominoes with a chicken?"

He conjures the lumpen despondency and hopefulness with the unforgettable simile: "He felt rather like someone lying in a bath after all the water has run out, witless, almost dead."

And then there’s the preposterously poetic and maddeningly meandering: "The day before him stretched out like an illimitable rolling wonderful desert in which one was going, though in a delightful way, to be lost: lost, but not so completely he would be unable to find the few necessary water-holes, or the scattered tequila oases where witty legionnaires of damnation who couldn’t understand a word he said, would wave him on, replenished, into that glorious Parián wilderness where man never went thirsty, and where now he was drawn on beautifully by the dissolving mirages past the skeletons like frozen wire and the wandering dreaming lions towards ineluctable personal disaster, always in a delightful way of course, the disaster might even be found at the end to contain a certain element of triumph."

It wasn’t until after Lowry’s death n 1957 that Under The Volcano’s reputation started to gain momentum. He was buried in the churchyard of St John the Baptist in Ripe with seven mourners at his graveside. His epitaph (which he wrote for himself) read: "Here lies Malcolm Lowry, late of the Bowery, whose prose was flowery, and often glowery. He lived nightly, and drank daily, and died playing the ukulele."

The writer had imbibed some 30 amobarbital tablets with copious amounts of gin. Many believe it was suicide, although the coroner recorded death by misadventure. His premature death at 47 could be regarded as a waste, but few – if any – drunks leave behind a work as towering as Under The Volcano. Lowry tackled the manuscript with the tenacity and bloody-minded dedication the chronic daily drinker tackles cans of Special Brew at 7am, and given the mountain he gave himself to climb, it’s not only a work of flawed genius but also something of a miracle.