Last summer, M.I.A. debuted a fashion line of sorts on Infowars, the platform of far-right conspiracy theorist Alex Jones. The centrepiece was a high-end tinfoil hat which purports to protect wearers from harmful electromagnetic waves like 5G. She demonstrated the hat with a matching “full-protection poncho”. Fans watched, begging for some layer of irony or misunderstanding to explain how she’d ended up there.

This wasn’t the artist’s first run-in with conspiracy, or with Alex Jones. In 2022, she defended Jones when he was ordered to pay damages to the families of Sandy Hook victims after he repeatedly claimed that the 2012 massacre was staged by actors. “If Alex Jones pays for lying shouldn’t every celebrity pushing vaccines pay too?”, she wrote on Twitter/X.

M.I.A. has never been afraid of controversy. She uses provocation in her music, videos, and within any allotted media time. It’s frequently backfired, like in 2016, when she asked “would Beyoncé or Kendrick Lamar say Muslim Lives Matter or Syrian Lives Matter?” in an interview with the Standard. Sometimes, the backlash is overblown, like when she was fined $1.5 million by the NFL for briefly showing her middle finger to 167 million people during Madonna’s Superbowl Halftime show. But with previous controversy, M.I.A. at least felt like a skilled provocateur on the side of a worthy cause, albeit clumsily.

Perhaps more than that, she’s stood as a cultural predictor. To review her career is to map the course of digital culture across the span of twenty years, from DIY idealism and deterritorialisation, through to growing surveillance and paranoia. The maximalist industrial hip hop and cacophony of her 2010 release MAYA was initially met with confusion by swathes of the music press, but it’s become a prescient touchstone for 2010s “internet music” and an example of digital overload explored through art. Now, stood up there donning tinfoil, she typifies the tired internet of today – overstimulated by corrupted information, knowing too much and nothing at all.

The paranoia is perhaps understandable. Growing up as a Sri Lankan refugee and daughter of an activist father in the Tamil resistance movement, her early childhood was one of distrust and upheaval, and her life post-fame has been dogged by near-constant scrutiny. The political thrust of her art led to two visa denials to the United States in 2006 and 2016. And as the barrier between listener and artist shrank throughout the decades, we soon knew far too much about M.I.A. Anyone could freely comment on every thought she shared online and in her music, and that’s led to her becoming more troll than artist at points.

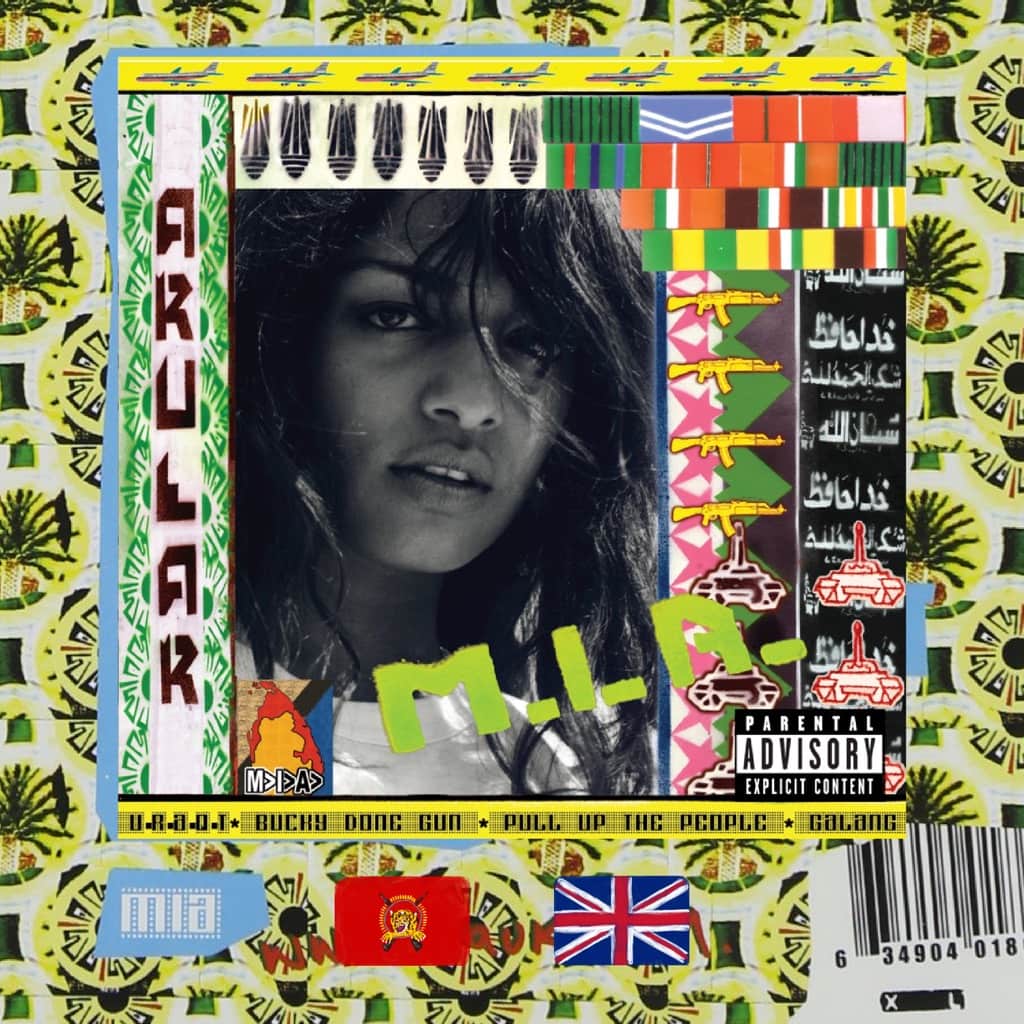

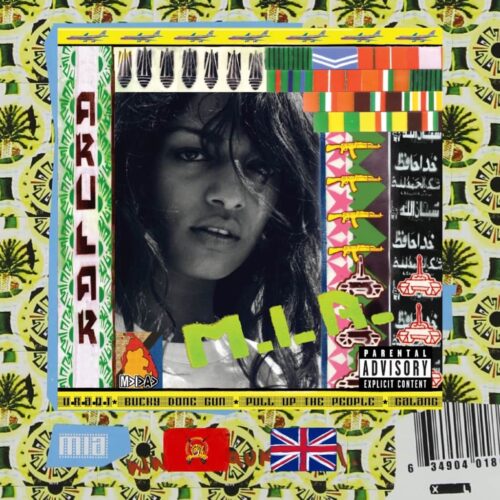

The M.I.A. of 2005 could be mysterious in a way the M.I.A. of today can’t. Hearing ‘Sunshowers’ for the first time or seeing the cover of Arular with its spray-painted tanks and bombs, free of the digital commentary of 2025, brought with it newness and optimism. She gleefully fused disparate cross-continental club sounds, crate-digging to show connections between cultures. The record presents immigrant status as an empowered sense of borderlessness, an unstoppable force, and an international community connected through beats. Arular is scattered in influence but unified by theme.

Her lyrics are just as strong in their collage approach. Freedom fighter chants are spliced with street slang, cryptic jokes and parts gathered from her trips back to Jaffna when filming a student project while at Central Saint Martins. With those films, she wanted to create art that favoured social realism above conceptual gravitas. Her music does the same with its candid, confrontational edge and a scrappy digital-age approach.

The rawness stood out in 2005, as did her layered social commentary, which worked more with attitude than with nuance. This is untouched with 20 years of distance. Songs like ‘Pull Up The People’ and ‘Sunshowers’ hit with the same heft they always have. But as with any iconic release, no matter how forward-looking, there’s a hint of nostalgia for a time when we didn’t know the full picture of her past or our future, when possibilities hadn’t yet crystallised into one point.

Before knowing the backstory, it felt as though M.I.A. herself arrived fully formed with ‘Galang’, Arular’s first single. As Nick Hugget of XL Recordings tells it in the 2018 documentary film MATANGI / MAYA / M.I.A., she “just sort of turned up at the office one day” with four songs from the record, ready to rap. In truth, M.I.A. had been a known entity for a couple of years, having been nominated for the Alternative Turner Prize in 2002 for her visual art. A few years before, she became friends with Elastica frontwoman Justine Frischmann after meeting at an Air concert through a mutual friend. Frischmann loved her art, with its stencilled graffiti of civil unrest, and took her on to film her tour, design single art and direct music videos. Though not a massive lover of Elastica’s music, the tour and their friendship embedded M.I.A. within an influential circle, and introduced her to electroclash hero Peaches, who loaned her a Roland MC-505.

Still, none of this background could have given M.I.A. the self-taught command she has on record. In the video for ‘Galang’, she raps against a greenscreen, with those colourful pops of her graffiti behind her. Even in that short clip, you can see the danger and freshness she could bring to the pop world while working from the inside.

Despite the near-instant buzz it afforded her, it wasn’t long before M.I.A. became frustrated with labels, industry and management. Delays to the release of Arular gave her the motivation to release Piracy Funds Terrorism a semi-improvised mixtape made alongside her production partner Diplo, who she had met at a Fabric night where he was DJing. The tape features pieces of M.I.A.’s vocals from Arular mashed up with bootleg samples of pop songs, baile funk instrumentals, and Jay-Z, Clipse and Salt-N-Pepa tunes.

Though pressed with the blessing of the label to be passed out at clubs and shows, the tape still embodies the exciting lawlessness and anything-goes spirit of the mixtape era. It revelled in the access to new sounds afforded by a flourishing social internet, and it was file-sharing sites and blogs where it would flourish. Even though the mashups are as fresh as they were when released, the tape has fittingly become an obscure internet relic, hard to track down outside of dodgy YouTube rips like many classic mixes of the time. The mixtape format would become one M.I.A. excelled at. 2010’s Vicki Leekx might be as essential as any of her records, even after it head-scratchingly became an NFT in 2021.

Diplo and M.I.A. would become firm collaborators for a large part of their rise to collective fame, and his brash brand of retooled dancehall and baile funk are all over ‘Bucky Done Gun’, where he found ways to make grating resampled horn flips work far before Hudson Mohawke would make it his signature. They’d go on to make ‘Paper Planes’ together, and date on and off until their relationship turned sour. Diplo later claimed to have discovered M.I.A. in an interview, to which she responded, “It’s important you don’t see me as a lil’ thing Diplo discovered because I’m a brown woman… this is the first story of a brown female musician who smashed it for the first time. That didn’t happen because I accidentally walked past Diplo.”

Diplo’s career has been dogged by darker controversies than M.I.A. and her hat, with allegations of revenge porn and abuse alongside criticisms of cultural appropriation for his approach to borrowing from the global club underground. (“What kind of music am I supposed to make?”, he told the Guardian in 2018. Being a white American, you have zero cultural capital, unless you’re doing Appalachian fiddle music or something. I’m just a product of my environment.”)

Through the Diplo lens, ‘Bucky Done Gun’ could be viewed in retrospect as a hard-hitting albeit frivolous party tune. M.I.A. shouts out London, New York, Kingston and Brazil, and raps in a Missy Elliott flow. She’s acknowledged that the chorus doesn’t really mean anything. Both its creators are having fun grabbing pieces of other cultures that sound cool to them and trying them on.

But that lens denies that the song and its central creator do have a point of view. M.I.A.’s early music is carried by its simultaneously hostile and utopian immigrant perspective. It’s there in ‘Pull Up The People’, where she makes fun of how white people might view her based on appearance and family name (“I’ve got the bombs to make you blow / I’ve got the beats to make you bang”). It’s there too in Arular’s skits, like ‘Banana’, where she riffs on how immigrant children are taught English in Britain with a playful scoff. An immigrant woman, a Tamil and a Londoner, no rapper looked or sounded like her. She made each characteristic a source of pride and tension.

Of course, M.I.A.’s intentions were often misunderstood, and she has had to restate her aims in increasingly bold and occasionally obvious ways to hammer home the point. In the years after Arular, the Tamil genocide in Sri Lanka grew deadlier, and M.I.A. became a target of the Sri Lankan government for speaking out against it. In an excruciating Bill Maher interview from 2009, she struggles to outline why genocide was taking place as Maher belittles the issue by pointing out her British accent. Here, the reason for her growing bitterness and distrust becomes obvious: “It’s interesting that with recent events, it hasn’t found a headline slot in the American media”, she says. “Most of it has been sourced on the internet, and the American public has to go on the internet to source out the truth.”

M.I.A. was a cultural predictor for most of her career not through clairvoyance, but through experience and necessity. What first began as a sensible search for truth became an addictive habit. Now that we’ve all become paranoid and overstimulated, she’s right there with us, not predicting mass culture, but drowning in it.

In the late-80s and early-90s when M.I.A. still lived in Brixton, she first discovered hip hop not through digging for information online, but through hearing beats through her neighbour’s walls. That newness likely hit her as Arular did for many. More than a fresh sound, what these discoveries do is make global mass culture personal, one voice speaking to you through a sea of many. Twenty years on, you can listen to her voice through the noise as clear as ever, no matter the chaos that’s come since.