"It may have been on a smaller scale, but for people of a certain age JJ72 were their very own My Chemical Romance." – Designer magazine, July 2005

"People don’t believe me," says a cheerful, amiable Mark Greaney, ex-singer and guitarist of JJ72, former childhood hero. We’ve got him on the phone. I am Christian Bale in Velvet Goldmine. "Always getting in a taxi in Dublin, especially if I have a guitar with me, the driver will go, "Oh, you play the music do yer?" and he’ll ask, "Do you know U2 do yer?" And I’ll go, "Yeah, I actually toured with them once." "My arse you did. My fucking arse you did." And he’ll ask, you know, "What was the name of the band?" and it’s always the same response. I go, "Oh, years ago, a band called JJ72–" "JJ what? Never heard of yous. Never heard of yous." You know the way the international kind of speak for a taxi man is. "I never heard of yous – you don’t exist – you’re not important."

We are quizzing Mark about events recalled from his old band’s dalliance with eminence around the turn of the Century, and congratulating him on the tenth anniversary of the release of the eponymous debut album (re-reviewed below). "I’m glad someone remembered," he chuckles as we introduce ourselves.

You come to imagine, via anecdotes like Greaney’s, that the experience of the vast majority of bands who make the initial ascent to ‘importance’ can’t be far removed from that of the Brave Volunteer plucked by a stage magician onto the boards. They’re flattered, befuddled, congratulated magnanimously on their bafflement, then tossed back tracelessly into the oblivion of the auditorium.

As a pair of staunch JJ72 fans, we have come over the main part of the last two decades to feel a little like stooges ourselves – beguiled, though, less by the capriciousness of the industry, than by the mass disappearing act that’s enveloped fellow admirers of the material. There must be others somewhere? Greaney informs us that some still do get in touch with him. Although it turns out a fair contingent of them are apparently teenagers (likely younger siblings of initial devotees) – some from as far afield as Mexico. But where have their older brothers and sisters – that first wave – receded to? Algeria?

We recall a band that inspired a palpable devotion, were tipped for greatness across the music press, and left as a memento of their stay a Gold-selling album that shifted half a million copies and spawned 3 UK top 30 singles.

"We don’t make any more money than our friends with proper jobs at the moment," they told Rob Fitzpatrick, then of Melody Maker, in an interview in 2000. "But they don’t get flown first class, get put up in fancy hotels and have people buying them drinks every night!" This, clearly, was attainable – if they had done it, well then so could we. Then, tragedy – the second album bombed. The pretty bass player [Hilary Woods] left the band. They disappeared for two years. The band almost made a comeback, poised with a third LP…Then they split up for good.

What happened?

"The drummer was great, the bass player was quite nice too, but the singer was a total arse, really up himself," says Rob, now. Remember though, these kids were only just 20 – if our band had had a gold record at that age, we could be forgiven for thinking that the sun shined out of our behinds, too.

But where did all the other JJ fans go? Are the authors the only two left in Britain? And what became of the band members themselves?

How does it feel now that it’s been 10 years since the first record came out?

Mark Grearney: I’m glad someone remembered! It’s a bit freaky, considering I don’t feel like I’m a 30-year-old man. Time’s gone so quickly.

Has it been spent wisely?

MG: Part of the time, yeah. A lot of time spent unwisely in-between. I’m glad that people still get in contact with me, like yourselves. From all over the place, from places that, twenty years ago, when the JJs existed, when we were touring the first record, places that I never knew the music would get to. If someone had said to me then, "In ten years time, 16-year-old kids from Mexico are going to be e-mailing you," I’d be like, "Yeah, right." It’s a good feeling, I think the first record is one of those records that has been passed on to little brothers and sisters, that sort of thing. A lot of people e-mail me who are a lot younger, you know, "Oh, yeah, yeah, I know of you, from way back, you old man you…"

The record was quite the success when it was released. Did that initial success surprise you? You were a young boy when you started doing this, was it a shock to suddenly sell half a million copies?

MG: Yeah it was. I think it’s more with hindsight, as with most things, that you realise what a big deal it was. Because I think, like most people, when you’re that age, when you’re young, kind of late-teens, you want to take on the world, and you expect the world to listen to you a lot. I suppose it’s a real exuberance, when you’re in your teens you can have that kind of naivety. And that’s why, at the time it was just like, this is meant to happen, you know?

Are you still in the business? Still making music?

MG: Yeah, still making music. In so far as, I suppose, a little bit more in solitude. So it’s a different kind of method. I think the band that we were in, we went through, obviously, that success with the first record. Then through the kind of cliched mill of what the music industry is. I was always very cynical of it anyway, from day one. Unfortunately nothing from my experience of the music industry disproved my suspicions. I think what being part of that business really freed me up to do, I suppose, is understand what I was trying to do more artistically. When I say I’m still making music, I’m still making music but I’ve got so many songs that I’m happy to write or record and not give them to anyone. That might sound like that defeats the purpose of making music.

Is that what you mean when you say solitude?

MG: Yeah. I think I’ve only reached that kind of happy type of solitude regarding making music now because of the big deal that was made out of JJ72’s first record, and because I was so young at the time, you know.

In many interviews we used to read with you it seemed that there was a certain band mentioned a lot, and that band was Joy Division. But in 1999 and 2000 no-one was listening to Joy Division, not until the movies and the explosion of Joy Division nostalgia. You guys were a bit ahead of the current curve there.

MG: I suppose so. I think, the thing was, we, I suppose I in particular, had such an obsession with the band, because I always used to go on in interviews and I still use the same language because it rings true, is that Joy Division always struck me as being like a separate entity. It wasn’t like they were part of any gang… Especially the people I was hanging around with, they didn’t know who Joy Division were, and that added to the allure of it, that you feel you’ve got personal connection with a certain type of music. Then obviously subsequently this, it didn’t ‘kick off’, but a load of these bands were aping Joy Division…guys pretending to sing in Ian Curtis’ voice…

Yeah, Interpol drive me up the fucking wall.

MG: It’s the kind of thing where, like any music fan, when one of your loves becomes popular again, and all of a sudden there’s high street shops selling Joy Division t-shirts… It is a bit unnerving, because, it’s not so much to do with the music, it’s more to do with the cycle of things.

That it has become fashionable again, that you’ve seen the decline and then the rising waves. 20 years too late and five years too early.

Yeah. It’ll always go that way. I suppose that’s just the way it is, so it doesn’t really matter; I think a band like Joy Division, when it just clicks with you for the right reasons you know yourself, ‘cos you can’t be dishonest with yourself, when you love something, you just love it. I’m sure there are lots of people who like bands that maybe their friends don’t like, but won’t own up to it, but they know themselves, whether it’s a bit of Kylie on the side… I remember, I had a heated discussion with a friend of mine afterwards who became one of the nouveau-Joy Division fans and she was telling me all about what Joy Division stood for, from watching the movie. And I just thought, that defeats the purpose! A movie can get you into a band, to a certain degree, but it shouldn’t be the be-all and end-all. It should be your own reasons that you can’t articulate. That’s why it’s just hilarious when the whole idea of a band now is, your way to make money now is to sell loads of T-shirts. It kind of, in some ways defeats the purpose of what artists should be trying to do.

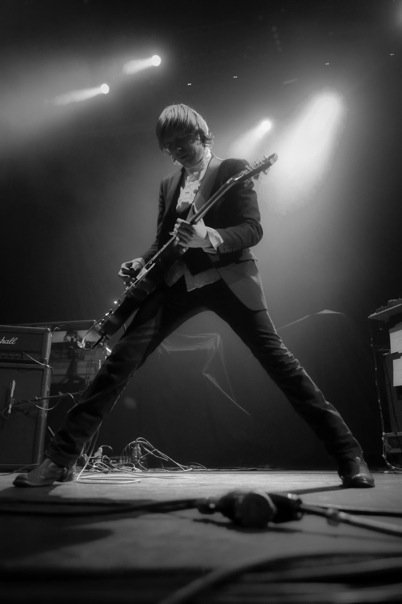

It worked for Ned’s Atomic Dustbin. You describe Joy Division as a separate entity. JJ72 struck us as, when you first started, you were all dressed in black, proper bands should be all dressed in black…

MG: Oh of course.

You didn’t really seem like part of any clique, whether that be representative of Irish indie rock music at the turn of the century, or any kind of lingering Britpop bands… Was it the case that you were trying to distance yourselves from everyone else?

MG: Yes, because – I’m not just saying this for the sake of it, but at the time when I formed JJs, I definitely was on a mission. I suppose the only thing I wanted to pinch from a band like Joy Division was the sentiment, and I wanted to make something, shape something sonically that instilled that sentiment. That was all that was important to me. It still is really, and that’s why it affects the solitude of making music now, I don’t really give a shit about music, generally, as a cultural movement.

I might be wrong about this, I might be making it up – it was some years ago. Did you tour with Coldplay and Muse? JJs, Coldplay and Muse – were you three on a bill together at some point?

MG: On two different tours. We did a tour of the States with Coldplay, and then we did a tour of Europe with Muse.

Not as part of a clique or an emerging scene necessarily, but your three bands were tipped by the music press back then to kind of be successors to Radiohead if the record that became Kid A had been a flop. Was there a great deal of pressure put on you then, recording your first album?

MG: No, not the first record at all, because when we recorded the first record, any attention we’d got up until that point we thought that every band gets that. We didn’t know that it was exceptional, you know. So making the record was no pressure. But I think it had an impact on our second record, in a big way. Because it had all built up, and we missed the point, a little bit. Sorry, heh, we didn’t miss the point, I think people around us missed the point.

Yeah, I dunno, the thing is – how do I describe it? Looking back on it, there are a lot of ways I was my own worst enemy regarding what I wanted to achieve creatively. I don’t know if I had the armoury at the time to achieve what was in my head. When we went to make the second record I was determined that we did it with Flood, and I don’t think he would have been the producer of choice for the label. Myself and Flood used to have very long discussions about what we wanted to create in the studio, so instead of just going in with a song and going, ‘Ah, here it is! Here’s the verse, chorus, verse,’ blah blah blah, there was a lot of discussion about what I wanted to articulate through music that I make. Which sounds like a really obvious thing, as if all bands do it. But as I learned to my surprise, a lot of bands who come out with hit after hit don’t do that. Their producers: they sit down, they make another hit… I was averse to doing that. That’s why I was my own worst enemy. If we had really wanted to end up being a really big band, then that was the crossroads. The decision to make the second record the way we made it, or make it in a different way.

Some bands survive the departing of a member; Mark E. Smith has built his career on it. Did things start to unravel around the time of Hilary leaving? Wasn’t that during the tour of I To Sky?

MG: It was after, we’d released one single, and it was coming up to the release of the second single, so it was at the end of a really long European tour. It had a big impact, but I think there was a point before that where the band… Something went wrong, I think it was when we made the second record. We went on a huge tour, which we shouldn’t have gone on, in retrospect. I just stopped writing songs. Creatively, the band stopped moving forward. Which was exactly what we needed to do, at that time.

Yeah, take a break, regroup.

MG: Yeah, exactly. Even though we had management, these people all around us and all this, no-one, my only gripe you know, my only problem I have with the history of the band, and this is genuinely the only one, was I wish someone had come along to us and gone, "Maybe just take a month, month-and-a-half, at home, in Dublin, back with your family, and think about things, and just chill-out." Really, it was a horrible time because at the start of that tour, when we released the album, someone really close to me died as well. It was only with hindsight, again, that I realised, I should have gone, "I don’t want to release the album if possible, ’cause it’s not a good thing to do right now." But that’s just part of the history of the band. I think Hilary leaving was I suppose – yeah, of course it was a big deal. The band was based on this synergy between the three of us, when we played live in particular.

Are you still in touch with Hilary or Fergal?

MG: I haven’t talked to Fergal for a while now. We’ve stayed in touch, but, kinda… sporadically. I think Hilary’s getting back into music, last time I talked to her.

Oh yeah?

MG: I’d formed a band called Concerto For Constantine, we’re more a live band, we just played live. And she came to a couple of those gigs. It was nice to see her down, you know. So, yeah. We’re still in contact. But lives go off in different directions I suppose.

Concerto For Constantine supported the Pumpkins, which must have blown your mind. [It is on record that Mark is a massive, massive Pumpkins fan]

MG: It was brilliant. We’d only just formed the band, myself and my mate Gavin. We’d formed the band really to just be extremely loud live. The same kind of thought hadn’t gone into it which made the output in the JJs, like songwriting-wise. A more immediate, more visceral kind of thing. We knew we wanted it to be like that. So we’d only just formed when the Pumpkins asked us to support them, so I was just… yeah. I was jumping around the house just going nuts, you know.

Did you get to meet Billy?

MG: Er… Briefly yeah, but I do remember someone from his label came into our dressing room and said, "Don’t talk to Billy today ‘cos he’s in a bad mood." Ah all right, yeah. But I’d heard these stories before, and I’d met him a couple of times when JJs toured America, he’d come down to our shows in Chicago, so I knew he was a fan. It was kind of disappointing I suppose, to see them on the way down, even though they’d reformed.

You didn’t like the last record then?

MG: Erm. I liked some of it. I still think – the word genius is bandied about too readily nowadays, but I do still think Billy Corgan is a genius. I think he’s a bit of a mental case, but I still think he’s brilliant. There are moments in the record, even guitar-part-wise, that are just like, "Woah." You can feel it comes so easily to him, you know.

Have you seen that TV advert for the American wrestling show, it’s Billy Corgan in a wrestling ring, reciting the entire lyric of Bullet With Butterfly Wings? It’s bizarre.

MG: He’s a big huge sports fan isn’t he, and he sings the national anthem before, what’s the Chicago baseball team, is it the Red Sox or the Cubs? But he’s a regular, singing the national anthem before the games there. That’s what I kind of like about the whole idea of him as an artist, is that he is a big kind of scatter-gun regarding what he thinks is important to say, at a particular moment. Even having the audacity to call the record Zeitgeist. When the irony of that was it was kind of, it was actually a bit passe in some ways. Sonically, you know. He convinced himself that it was the zeitgeist.

Did you get to tour with or play with any other childhood musical heroes of yours?

MG: I do remember, we did some touring with U2. That was the Big Deal. I’d always obviously been aware of U2, like everyone is, but I’d never been an über-fan. When we first supported them it was an emotional moment, they were just so powerful live, ’cause we’d never seen them live before. So little things really stuck out. It was the one where they had the hearts, kind of runway thing where you’d walk out and it’s one of his ego-ramps… The Elevation tour. Myself, Hilary and Fergal were standing inside the little sealed-off section, so we were in the middle of Bono’s ‘ego area’, and I remember him leaning down to us, and in the middle of a song thanking us, and the whole stadium cheered, and we were like, "Fuck, this is brilliant." They don’t dissipate, moments like that. They just stay there forever. So, stuff like that, you know, people don’t believe me! Always getting in a taxi on the way to the airport in Dublin, you know, the taxi driver will kind of – especially if I have a guitar with me, he goes, [Dublin accent] "Oh, you play the music do yer?" and he’ll ask, "Do you know U2 do yer?" And I’ll go, "Yeah, I actually toured with them once." "My arse you did. My fucking arse you did." And he’ll ask, you know, "What was the name of the band?" and it’s always the same response. I go, "Oh, years ago, a band called JJ72–" "JJ what? Never heard of yous. Never heard of yous." You know the way the international kind of speak for a taxi man is. "I never heard of yous – you don’t exist – you’re not important."

Do you ever listen to JJ72 these days?

MG: Funny enough, I would the odd time listen to ‘Sinking’, which is on the second record. I would have bought that song, if someone else had written it. I don’t mean that in any sort of arrogant way. I just mean it’s like something about that song that I like to listen back to, ‘cos it doesn’t feel like it’s me.

There’s nothing wrong with taking pride in your work.

MG: But it’s not even that. I wouldn’t listen to, say, the first record, or most of the second record. I haven’t heard the first record for a long time, and that’s the truth. I think I’d be scared to listen back to it in full because I don’t know if it would stand up sonically, because I know that parts of it – even, I remember at the time when it was released, I remember songs coming on the radio, and it was just really quiet. And also I remember feeling it was a very slow record. But I don’t know, I haven’t listened to it, I probably should.

Anyone can be loud, it takes balls to be quiet. And it’s really, really good! Everybody is always hyper-critical of their own work. Even Butch Vig says that when he listens to Nevermind, that he can hear all the ‘mistakes’ in it, you know.

MG: Yeah I ‘spose so.

What became of the third record? Was it all put together and ready to go?

MG: Yeah, it was all mixed and mastered and everything. And it was made – pretty boring, this, but it was made around the time Sony/BMG merged properly. The guy in Sony who more or less championed us moved on, shall we say, to a different job. So the whole line-up of people changed in there, and we were put to the back of the queue, a very, very long queue. "Oh if your next single doesn’t go Top 30, then we don’t know if we’ll release the record," all this sort of stuff. So that went on for a while, so instead of that just perpetuating we decided to call it a day. But it’s weird, because going back to what I was saying, creatively I’d almost hit a wall, or decided not to do anything after the second record. So even though I wrote the third record and we went through recording and everything – it’s a good record, a pop kind of record, but I don’t think it had the emotional punch of some of the songs on the first or second record. I don’t think it was any bad thing that it was never released. Most of the songs I think one can get on the Internet in some way or the other. I’ve got a website going up in a couple of weeks. I’m gonna put up hopefully most of the third record on there anyway, so people can have a listen to it.

It will make for very interesting listening. Outside of us, do you have any weird fans? You mentioned Mexican teenagers.

MG: I think a lot of JJs fans were always very… passionate. To say the least. And I really appreciate that you know! Because I think one of the worst things would be if I was looking back on the ten year anniversary release of the first record, and if all the fans just faded off into the distance after six months or something, it’d be quite disappointing. But I do get people come up to me still quite a bit. Most people who do come up to me absolutely feel that the first record, or the second record, was written for them, as an individual, and they can put together some verses, and bars of choruses that they can mirror against certain encounters from their life, which I think is great, and I think it’s a similar thing with a lot of Manics fans, you know. We just had that, accidentally – we had that appeal to people who were, I just think really passionate about something. And maybe a little bit kind of romantic, in a weird way. Not in a kind of ‘I’m going to propose to my bird in Paris’ kind of way.

We have a memory of an I To Sky gig at The Forum in Kentish Town, our view of the stage was blocked by some bloke in his mid-40s who was basically mouthing all the lyrics, he knew the whole thing off by heart, and the album wasn’t even out yet.

MG: It’s funny, because I was talking about this, I did some recording in, erm, the Manics have a studio in Cardiff–

The Holy Bible studio?

MG: Yeah, yeah. The Faster studio. I did a bit of recording with their producer Dave Eringa in there last month, and James from the Manics was in, and we were having a chat, and we were recalling old days, we did some gigs with the Manics…

You shared management didn’t you?

MG: Yeah, we shared management, so that’s how I know them still. Not particularly well, like, they’re not mates, you know, but I know them to say, "Can I use your studio for a bit." James remembers watching us from the side of the stage, and seeing people up front, he said they were almost, almost singing, as intensely as Manics fans. I was like, "Great!" I dunno, I just took it as a compliment, because, you know I’m still a big fan of the Manics, and what they kind of inspire in people.

Looking forward to it. I’ve got one last really dumb question. Did anyone ever come close to finding out what the name of the band meant?

MG: Yeah I’m sure people have got it before. I’m sure I probably said it before, I dunno. Yeah, it’s pretty simple you know, it’s err…

I don’t think I want to know, I just wanted to know if anyone had guessed it.

MG: Someone had guessed it, and said it to me recently, and I didn’t say anything, whether they were right or wrong. But they were right.

JJ72 revisited, 20 years on…

October Swimmer

"It’s amusing how the UK is churning out Buckley-ish bands these days", went a Drowned in Sound article in October 2000. Cited as evidence, the trio of Muse, Coldplay and JJ72 – collectively the trident spear being wielded at the then-vulnerable neck of Radiohead. Of course, it’s a geographical error to claim that Dublin (this is where JJ72 are from) is part of the UK. But you hear the faded-in acoustic strumming – Mark Greaney quivering earnestly about "the dreams of dying mothers" – and why pick bones about geography? This might as well be a souped up version of the demo CD by that guy who runs the open-mic night at your local pub. Verse 2, an electric guitar bathed in reverb solemnly intones chord changes – as it would. Guess some sort of string section will stir into being next, then…

Ah. Here’s a pleasant surprise. 40-odd seconds in, drummer Fergal Matthews turns up and syncopates the entire thing by stamping over Greaney’s line about "barbed bones of futility" with what becomes the song’s defining, repeated hook – an impatient, militaristic stomp that for the rest of your life you’ll unconsciously pat out on your lap whilst attempting to solve logistical problems. Greaney, all bludgeoning epic power chords from hereon, barks a choral demand about wanting to be "a happy boy".

An unashamed, un-ironic, unsubtle, watertight, quiet-then-loud anthem. Not a note of virtuosity in it – yet more brashness and posturing than The Darkness. Ladies and gentlemen, JJ72.

Undercover Angel

A song that wouldn’t be miles out of place on a Smashing Pumpkins album creeps softly in from under the dissipating feedback of the opener. Lyrics evoke a beloved angel discovered in a river amidst lovely Arcadian things like stardust and golden spray. The logic of the previous track suggests this is a kind of wooing-in. Suspicions are confirmed as the line "but this shining flower knows it can sting" carries the song from bucolic strumalong to surging stormfront, and Greaney’s vocal soars near-seamlessly from admiring croon to a scorched lament. He was trumpeted much for his falsetto range, but his real vocal talent was in making his often awkward metaphors ("being sentenced by a pilot / to my dreamland cross") sound irreplaceable and his earnest melodramas come across as compellingly archetypal.

Oxygen

JJ72’s second-biggest hitter. Mark Greaney once hypothesized in a Drowned in Sound interview that had he filled his second album with ‘Oxygen’, he would be playing the arenas that Muse later claimed. JJ72 show that they’ve got this anthem thing down a trick – to the extent that each verse here ends by grinding the song to a pause in anticipation of the singalong chorus ("you and I / we’re going so high…") The whole thing’s smothered in strings, though, and ends with a 40-second violin coda. The sense of ambition and gravitas that wove through the previous two tracks is here flanked by late-’90s indulgence – ironic for a song that seems primarily to be about lack of need. First part of the album where it begins to feel repetitive.

Willow

Repetitive, you say? What, then, about a gentle ballad of acoustic guitars, swooning strings, flourishes of piano? "By the old wood / burning / in the garden. / As the moths fly / through the flames like / our little Holland." If the word ‘earnest’ could aptly describe the album’s sound at large, ‘sincere’ captures this breathy piece. It is what it is – basically a testament song to the fact that the album was devoted to Greaney’s girlfriend at the time. The chorus brings to the fore his knack for internally simplistic, insistent melodies – which re-emerges in later tracks.

Surrender

An internally simplistic, insistent melody gives this uneventful song a hypnotic, spiralling quality. Two moody verses – melodically the same; one gentle, one harsh – argue with each other from either side of a chorus nicked off Nevermind. There is filler on this album and Surrender is it. The ricocheting feedback that carries it out says ‘latest Radiohead clone’ (circa August 2000) like nothing else can.

Long Way South

High aspirations were declared via the opening tracks. Here – halfway into the album – is where they triumphantly pull themselves over the top. Any missteps or temporary distractions en route are redeemed by this two minutes and fifty-one seconds. Sparse, serrated guitar claws its way round an impellent drum-machine pattern – an interplay that seeks to channel Joy Division via the Pumpkins’ 1979.

Matthews joins in around the choruses to render them cataclysmic. Greaney shrieks a load of incandescent nonsense until his voice begins to break, and then a gothic, synth-organ delivers a full and frank response. To accomplish this sort of thing, you think – exhilarated – one would require a guitar, a bass, a drum machine, an organ. And that’s the genius of this band. It all sounds irreducibly simple. Why haven’t their competitors (who have had two decades to work something out) formulated any kind of half-convincing answer to Long Way South?

Snow

Speaking of the bleeding obvious, why hasn’t anyone penned a song about how unsatisfying it is to discover that a predicted snowfall hasn’t crippled the local infrastructure – or simply hasn’t occurred at all? Well, the JJ’s have, and it was their highest ever UK charting at 21. It’s probably the most satisfying lyric of the set, capitalising on their quiet-loud formula to the extent of dramatising it. An observer, whose health is in an unexplained state of decline – watches from the subdued verses as "children go cursing at their only cause" in the choruses – that ’cause’, of course, rousingly bellowed at the heavens with the assistance of a couple of Marshall stacks. Depending on your sympathies (verse or chorus, essentially), this could be anything from a concise summation of teenage angst to (so I’ve been unreliably informed) having ‘something to do with the potato famine.’

Broken Down

Back in the days when it were all on CD you’d sometimes be surprised by the emergence of a hidden track whilst peeling onions or cleaning shoes or something. Similar feeling when the drone note of this song rattles out of a silence. We’re in the midst of some kind of interlude – where the ‘big’ songs take a break. So, otherwise unaccompanied, Greaney picks out a simmering, sparse melody on his electric and goes all Book of Revelations on your ass. Actually, there’s little coherent indication as to what the ‘meaning’ is but all the key phrases are there to paint a grim picture. "Saints cannot flee the strength of the call!" he roars with the bilious conviction of…well, someone intoning a heavenly war. "Crimson handed fiend / of hate strokes the soul of all!" he accuses, attacking his guitar with the same intensity he does his larynx. There’s a stunning audacity to it. James Dean Bradfield – back in earlier days – could probably have got away with declaring his antagonist a "crimson handed fiend". Few others. If this weren’t as transfixing as it is, it’d just make you laugh. It was very rarely performed live. You get the impression that if he’d attempted it live he’d’ve broken his leg or something.

Improv

Another single-hander, perhaps a kind of rebuttal to what we’ve just heard. A warm, melancholy, acoustic number where Greaney flits despondently between registers and octaves. The album would be no worse lacking this ‘yang’ to Broken Down‘s ‘yin’. Having said that, it would be no better either. And it does contain the funniest line – "They will never fool me / and in-te-grate me as a clown!"

Not Like You

The album hits its first dud this side of Long Way South. A waltzing, Andrex-sponsored blub-fest with little bells that chime in every bar. The choruses gently nudge a lover to "please love me / sincerely". Greaney’s all fragile and delicate. Perhaps this is an attempt to breach the fundamental conventionality of the album’s song structures by inversion – i.e. loud(ish) then quiet. Fortunately, the collective inertia of previous tracks make this one fairly easy to overlook.

Algeria

The album rises once more to its feet for this triumphant stomper. If you know your seasons, you’ve got the song’s chant memorised: "Springtime, summer arrives, / summer dies, autumn arrives, / autumn dies, winter arrives / forever and ever…" Its simplicity allows it to be the kind of song that can go on indefinitely, and so has to be ceremoniously dissolved by deafening feedback and cacophonous cymbal crashes. These tools aren’t on hand, however, to assuage the insomnia derived from having it looped in your head.

Bumble Bee

The song feels perfectly adequate – even necessary – at the end of the album but has an anonymity about it which makes it pale in comparison to the hook-laden examples of the band’s better work. It’s a set and album closer; designed seemingly for that purpose. Ultra subdued, drifting, whispery verses are counterposed against ambushing choruses of noisy guitars and screamed lyrics.

"I sing my sad songs / and I hope forever", wails Greaney – almost incomprehensible in the racket. A throwaway line, really – some sort of Billy Corgan offcut – probably with little more than a minute’s thought behind it. But time makes it the highly appropriate parting shot for an album that serves as both debut and epitaph for this deceased band. There was a subsequent album – 2002’s I to Sky. Grand designs had been half hatched with Flood in production. The result came off as an unhappy welding of Placebo and New Order which is best – as it is – forgotten. A third album went unreleased – due to unencouraging sales of its initial (frankly mediocre) release She’s Gone. The band disintegrated soon after.