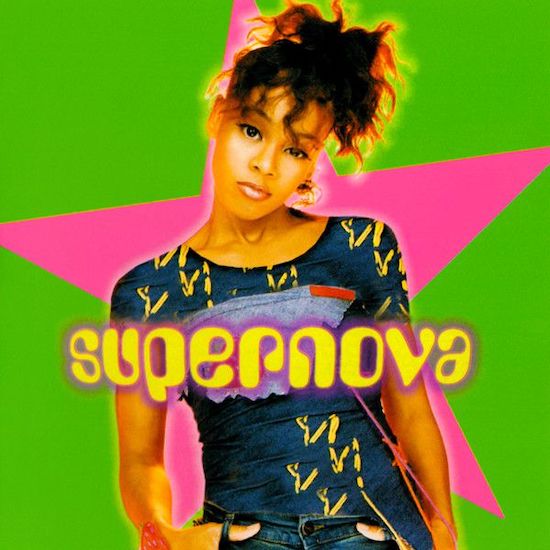

August 16, 2001, was supposed to be a big day for Lisa "Left Eye" Lopes. She’d settled upon it as the release date for her first solo LP for reasons that went beyond the commercial and scheduling considerations most artists have to juggle. It was the anniversary of her grandfather’s death, and would have been her father’s birthday, had he not been killed ten years earlier. To say the 30-year-old Atlanta-based artist had a complex relationship with her drill-sergeant dad would be putting it mildly, but she chose to close the LP with a song constructed as an open letter to him, and which found her clearly articulating her belief – apparently fused from equal parts science, tradition and wishful thinking – that energy is never lost to the universe, and that when someone dies, a new star is born.

If all you knew about Lopes was what was contained on Supernova, you’d be staggered at the breadth of her talent, the scale of her ambition, the depth of her apparently boundless empathy. But there was no way you’d have lit upon the record without knowing anything about her, which was at once the biggest advantage she should have had, and a burden no collection of songs could reasonably be expected to bear. A string of huge hits as part of the pioneering hip hop/soul band TLC – at the time, the biggest-selling all-women band in music history – had built significant and strictly defined expectations for her musically, while a near decade of front-page headlines provided plenty of fuel for lyrics as self-aware and soul-baring as anything pop had seen to that point, but also meant she was as contentious and as widely misunderstood as it was possible for a pop star to be in those early days of the 21st century.

Presumably it was somewhere in the middle of all that – perhaps in anticipation of a record that would dovetail more neatly into TLC’s storied discography; possibly with concerns over how some of the passages of explanation and self-justification might come across as unsympathetic – where executives at her career-long label, Arista, got cold feet. August 16 came and went; Supernova failed to appear in US record shops. The LP was released in Europe, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia – testimony to TLC’s global reach and acknowledgement that Lisa was a singular, powerful presence in popular culture worldwide: but back at home, the record was shelved.

Confused, hurt, and understandably angry to find that she’d poured herself into a project that those who had profited from her career failed to feel was important enough to even be given a chance in her own marketplace, Lopes retreated. She spent the next few months on reinvention, and signed to Suge Knight’s resuscitated Tha Row label as N.I.N.A. – a name Knight apparently coined in reference to a handgun but which Lopes said stood for New Identity Non Applicable, an apparently Prince/symbol-like device to create new music outside the contracts she was still signatory to as part of TLC.

The following April, Lopes and entourage, including the group Ejypt who she was mentoring, decamped for a month to Honduras, where she was in the process of establishing two children’s charities. The country had become a home-from-home: well-documented struggles with alcohol had been put behind her, in part thanks to frequent visits to the Usha Herbal Wellness Center, where she practiced meditation, communed with nature, and followed a plant-based detox diet. A few days before the party was due to return to the US, Lopes was at the wheel when her rented Mitsubishi SUV left the road, struck trees, and rolled over twice. Six of the seven people in the vehicle at the time sustained cuts, bruises and a few broken bones: Lopes was killed. It would be facile and sensationalist to suggest that her label’s failure to release the solo LP caused Lopes’s death: but the decision to shelve Supernova certainly set in train a series of events that culminated in that fatal accident. What is unarguable is that we’ll never know what might have been had this exceptional record been given the chance it and its maker so richly deserved.

At 20 years’ distance – and from what one always hopes is the present’s more enlightened perspective – Arista’s reluctance to release Supernova seems inexplicable. Nothing on the record tarnishes TLC’s legacy; everything on it speaks to the vast and still largely untapped potential of Lopes’ talent. If you’re being cynical you can consider it an institutional failure to understand and know how best to channel a determined, headstrong and singular woman – that the system was too readily willing to diagnose her as a diva and paint her idiosyncracies as defects or difficulties. Surely, today, a woman with a story to tell and a singular way of telling it would have been supported and empowered by the corporation she worked with – though of course, as Raye and her fans would point out, such marginalisation can still happen, despite all our claims and expectations to have learned from the mistakes of the past. It is perhaps instructive, if not at all heartening, to note that, in a week that’s seen the announcement that most of the back catalogue of her near contemporary in sudden and unexpected death, Aaliyah, will be released onto streaming services worldwide, Supernova remains available only as a secondhand, non-US CD.

On the other hand, if you’re willing to cut Arista some slack, you could point to a scattering of less-than-enraptured reviews from global media and argue that they called it right. Maybe Lisa was just too far ahead. As much as it’s a relic of a different era – an album from a time when the tabloid media held sway, when public figures didn’t have the option to broadcast their developing responses to the dramas they were living through directly to fans via their smartphones –

Supernova still feels like it’s doing something new. On it, Lopes spends far more time predicting the future of the several genres her music inhabits than she did worrying about the then-current state of the art in any of them. If those critics were disappointed that she wasn’t following Missy Elliott or Aaliyah or the Neptunes down what seemed at that point to be the road ahead for rap from the American South, they weren’t necessarily wrong: just perhaps lacking a little vision.

Perhaps because she didn’t have the kind of instant outlets for commentary that are available today, those non-musical channels for communicating with her audience, Lisa poured herself and her worldview into this hour of songs, knowing this was her best chance of speaking her truth and being heard. (More reason, too, for her to be hurt when that opportunity to speak to fans was denied her.) Certainly, from the very first written lyric onwards, Supernova has a resonance and a relevance that feels timely and contemporary. "Young woman confused, young woman abused," she begins on the summery, borderline euphoric ‘Life Is Like A Park’, addressing the lyric – perhaps the whole album – to both a specific and significant subset of her audience, and, surely, to herself as well: "You must understand it’s never too late to lose who you are/and choose who you are supposed to be/supposed to become." This was the lesson, you sense, she felt as though she was put on Earth to teach, and from that first verse onwards the record always retains a focus on empowerment and uplift that continues to engage and inspire.

Another key theme, subtly expressed but inextricably woven into the album’s construction, is what seems to be a prizing of the retention of a child-like gaze – an encouragement to try to pare back the cynicism and world-weariness that adulthood brings and to remember, at least occasionally, to see the world and its wonders in a less guarded, more innocent way. Lopes had adopted two children, and, according to her long-term partner Andre Rison, speaking in a TV documentary broadcast last year (part of the Lifetime channel’s mini-series, Hopelessly In Love), the pair had suffered two miscarriages. Again, we have to suspend the tendency to cynicism: the charities in Honduras were not projects of a superannuated star looking for an image-burnishing way of reducing the tax bill. ‘Life Is Like A Park’ sets out the stall, Lopes using the term not to refer to an area of land but as a playground, in the way a child, still building a functioning vocabulary, might conflate one with the other. The chorus speaks about seesaws and merry-go-rounds, not boating lakes or woodland walks, and the lyric lasers in on the basics: "Sometimes you may even fall down/and though you may get stuck/you must get back up".

The wide-eyed innocence and open-hearted love for life shines through most powerfully on ‘The Block Party’, a song that has few equals (perhaps only Lauryn Hill’s ‘Every Ghetto, Every City’ matches it for its ability to capture the power of music to unite a community while hymning the songs that the artist grew up with; though Missy Elliot’s ‘Back In The Day’ and 2Pac’s ‘Old School’ come close) and which still sounds otherworldly and futuristic today. Brilliantly underpinned by a Salaam Remi production based around a daringly minimal, zephyr-light mbira sample from Earth, Wind & Fire’s ‘Drum Song’ and given an unconventional, iconoclastic structure (the chorus is divided into three pieces which never repeat in the same pattern), the song hangs around two verses which paint two related portraits of childhood, friendship, community and music, seen through the eyes of a young woman at either end of her teens. In the first verse, the song’s protagonist is excited to play skipping games and drink soda pop while the favourite tunes of the day get an airing at the impromptu party that’s just broken out on a neighbourhood corner; in the second, an older teen is just as excited about the block party but this time it’s beers, boys and Run DMC that send her giddy.

A chanting children’s chorus gives the song a you’re-either-with-me-or-against-me defining/dividing quality, but the two most powerful statements arrive alongside that. Each verse reaches the hook via a conversational bridge, two different characters interrogating Lisa each time. After the first verse some children ask what her name is ("Lisa!") and where she’s from ("Ninth Street"), before asking "Where you going?" Lopes answers, "To the party", and then the kids ask if they can come along too. After the second, the same conversation takes place between a young man and a now grown-up Lisa, giving the same words a completely different atmosphere. Yet Lopes ends each section with the same wordless "ah-hah" of inclusion, affirmation and shared joy. If the listener can approach the song with the same kind of open-mindedness and spirit of adventure as the characters it portrays, the emotional punch these moments carry can manifest physically. And then, twice in the aftermath – placed different distances from the conversations and the chants – comes Lopes’ personal credo; a kind of mic-drop moment in terms of outlining who she is after having pithily summed up where she comes from emotionally and temperamentally. "I’m a big city girl from all over the world/And I do what I wanna do – right foot, left shoe". Universal, experimental, individual – inclusive, warm, joyful. In three minutes, the song does everything anyone could ever want from a piece of pop music, and any artist would surely be proud to have made it.

For the most part, Supernova is content to be a fine turn-of-the-century hip hop LP, Lopes revealing herself as a far more versatile rap stylist and a more nuanced and self-critical lyricist than she was given credit for in the few reviews that the record garnered. The posthumous (though uncredited, at least on the back cover) duet with her close confidante 2Pac, ‘Untouchable’, underlines certain similarities between elements of each of their approaches: but those who have dismissed her as largely in thrall to his style are surely mistaken.

She worked with other lyricists, and arguably the most personal of all the songs here, ‘I Believe In Me’, doesn’t see her credited as a writer at all. The song is apparently the work of Tracey Horton who, under the name Pudgee Tha Fat Bastard, released an album on the Giant label in 1993, and collaborated with Notorious BIG on the sample-clearance-denied underground anthem ‘Think Big’. In 2013, Pudgee told journalist Robbie Ettelson that Lisa had asked him to write her verse for ‘Untouchable’ almost as a kind of gift: he and Pac had been friends, and she felt this would give him one last chance to spend time with 2Pac in the studio. You sense the absence of her name from the credits to ‘I Believe In Me’ must similarly have been, at least partially, further evidence of her creative generosity: if he wrote all the lyrics, he can only have done so after extensive conversations with Lopes to figure out exactly what was going on in her head, making this a collaboration no matter who came up with the precise phrasing and who wrote down the final choice of words.

However the workload was divided up, her five collaborations with Pudgee are superb. On ‘Untouchable’ she matches Pac’s tone and flow syllable for syllable while never letting the listener forget who it is who’s rapping; ‘I Believe In Me’ is even better, the writing channelling Lopes’s anger and rage but leavening them with knowing self-reflection as she discusses the private truth behind the public image of fissures within the TLC ranks, this time the delivery recalling DMX’s bark and bounce. ‘Hot!’, the second track, is a garrulous battle-rap that finds Lisa calling on the gossip-hounds to quit baying with a piece of wordplay that underlines an implied kinship with Lauryn Hill and, by extension, Aretha Franklin ("drama comes in dozens and I know you love it/but a rose is still a rose so I rose above it"). And Pudgee also gets a credit for ‘The Block Party’, so may be who we have to thank for passages that showcase Lopes’s dextrous double-time flow ("grown folks gettin’ busy with the gigolos/drinkin’ Michelob/it was 6am before they hit the road").

In the heartbreaking documentary, The Last Days Of Left Eye, first broadcast by VH1 in 2007, you don’t just see the pain and confusion that overtook Lopes after this LP was left on the shelf, but you come to appreciate how, mere weeks later, she’d already moved herself forward, emotionally and philosophically. That closing message to her late father, ‘A New Star Is Born’, helped her find some kind of closure in the relationship she seemed to stop short of describing as abusive, but which most others – including even family members – consider to have been. "Tumultuous" is the word most frequently deployed to describe her relationship with Rison – two fires in bathtubs, one ending with a gutted Atlanta mansion, being the headline-grabbing incidents – yet Lisa famously turned the court-mandated halfway house stay into spun gold when, on the way to the studio during that period she saw the rainbow that she wrote into her timeless verse in TLC’s ‘Waterfalls’. She always found the strength to overcome. So we shouldn’t be surprised, when we check in on those last weeks, to see her emboldened, phlegmatic, optimistic. That’s who she was when she was making Supernova, too. You can hear it in every bar of this overlooked masterpiece.