For a short but glorious moment, Levitation looked like they could conquer the world. You may or may not be acquainted with their debut album – it will depend upon whether your interest in early 1990s indie rock borders on the fanatical, or you at least lived through it – but, upon its Spring, 1992 release, Need For Not went straight to the top of the Independent Charts in the UK.

The album earned them a deal with Capitol Records in the US – offered by Alison Donald, the woman who went on to pick up The Strokes, Gnarls Barkley and The Gossip – and helped add to a fanbase that already included soon-to-be influential figures like Damon Albarn and Radiohead, who opened for them at London’s Astoria exactly a month after the album’s release.

For Terry Bickers – unceremoniously dumped two and a half years earlier from a tour bus on the side of the road outside a remote Welsh train station after being evicted from The House Of Love, one of the most hotly tipped acts to have emerged in the late 1980s – it was retribution or, at the very least, affirmation that he’d made the right move leaving behind a band that had been increasingly stifling his creativity in favour of tracking his own muse. Twenty years later, however, Need For Not remains little more than a footnote in the history books. Life is sometimes more than a little unfair.

Bickers – a dead ringer for Carl Barat, and blessed with a similar charm and charisma – had pursued a musical journey since that ignominious departure that was as unfashionable as it was unlikely, gathering around him four likeminded souls eager to venture beyond the prevailing musical trends and willing to work as hard as necessary to achieve their goals.

A number one indie album was a sweet reward, but it was to prove a Pyrrhic victory – the attention devoted to some of Bickers’ more eccentric pronouncements wore a man down who was already given to self-medication, and the relentless schedule endured by the band left them exhausted and fragile. In the end – and the end was already not far off – the musical differences that had at first inspired them contributed to further friction, and they combusted publicly on stage in London a year after Need For Not‘s release.

Their second album – Meanwhile Gardens – was in the can, but only ever saw the light of day in Australia, partially re-recorded, Bickers’ vocals replaced by someone described to me recently by drummer David Francolini as "a vapid, careerist fool of a man and a complete waste of time". The magic of Levitation vanished as swiftly as it had materialised, but what they left behind proved it was no illusion.

What Need For Not did – and it did it with style, conviction and confidence – was to combine Bickers’ remarkable guitar skills with a ferocious rhythm section driven by the deranged but taut playing of drummer David Francolini and former Jazz Butcher bassist Laurence O’Keefe. They were joined by keyboardist Bob White and his friend, the cherubic former Cardiacs guitarist Bic Hayes.

It was in Hayes, whose guitar playing would have stolen the limelight in almost any other band, that Bickers found the perfect foil for his own talent, one often compared to Kevin Shields’, and the record paired a wild, audacious, even romantic desire to create a music that existed in another dimension, well beyond the humdrum, conventional modern world, with the more vulnerable tones of Bicker’s vocals, the eye at the heart of a savage storm. It also exploited five men’s exceptional musical skills, deployed through extended, frequently drug-fuelled improvisational sessions, to deliver nine ambitious yet devastatingly focussed tracks that drew upon a diverse range of influences, from Can to Killing Joke, from The Cardiacs to Julian Cope, from Television to Talk Talk.

Need For Not didn’t by any means represent their first recordings. The band had already released enough material to fill Coterie, a compilation album for their first label, Ultimate Records, and had also spent months on the road, quite apart from in their lock-up, refining and enlarging upon songs until they were satisfied. All members of the band took part in an unusually democratic writing process, contributing both music and lyrics, and their live shows left plenty of room for them to explore new avenues. Demos recorded between 1989 and 1991 – made available on cassette to their fan club members in late 1992 – revealed the manner in which songs had developed between conception and final recordings. Most had muscled up considerably, but Levitation’s approach was nothing if not carefully considered: any added weight was there for the sake of the songs rather than to illustrate muso tendencies.

"Music by Heads for Heads" was how Francolini recently described it – perhaps riffing on Spacemen 3’s 1990 album title, Taking Drugs To Make Music To Take Drugs To – but it was undoubtedly music for the mind. It challenged its audience, bending songs in unexpected directions without leaving time for their twists and turns to be questioned. While rarely too ‘busy’, these tracks still offered numerous ornamental flourishes that sounded both inspired and entirely distinctive. The baroque harpsichord that introduces ‘Hangnail’; the cheeky two note riff, treated differently each time, at the end of every line in introductory single ‘World Around”s verses; the shattering of ‘Pieces Of Mary”s pastoral, acoustic opening phrases with a guitar chord that trembles over blacksmith’s drums.

The House Of Love had looked set to be huge when they released their debut for Creation Records in 1988, and their career path seemed to have crashed under the weight of both subsequent expectations and Bickers’ departure. There were high hopes for Need For Not, therefore, and not just because the prevailing opinion was that Bickers must have been the true genius in his last band. Melody Maker’s Steve Sutherland had already declared that Levitation were "fucking great, the greatest we have right now". But, as the group’s de facto focus, Bickers had also gained a significant profile in the music press – more significant than he ever wanted or knew how to deal with – for behaviour as maverick as his guitar playing, beginning with apocryphal tales of his setting a light to bundles of money in the back of the House Of Love’s tourbus, moving on to advising BBC2’s Rapido TV show that the band would be upping sticks to join a commune in Holland (or perhaps Czechoslovakia), and furthered by rumours of his arrest after defacing billboard posters with political slogans. ‘Bonkers Bickers’, the press called him, and this growing circus not only threatened to overshadow the band’s music, which genuinely seemed to be the prime motivation for their existence – something emphasised by Bickers’ comment to Volume magazine that the band should "remain faceless for as long as possible; maybe we’ll take to wearing masks" – but also affected the manner in which people perceived it. Alongside grand, spiritually inclined statements to journalists like, "I think we need to find somewhere where we can go and get in touch with nature and hug a few trees", the complexity of their songwriting provoked frequent use of the word ‘prog’ in their vicinity. "Are Levitation too far out?" Melody Maker was moved to wonder. "While other bands take it one step at a time, have they leapt into space and severed the umbilical cord?"

So when the record was released by Rough Trade on May 4, 1992 – accompanied by press ads announcing "May The Fourth Be With You" – it was subjected to rigorous scrutiny that perhaps placed the emphasis on the wrong features, NME’s Stephen Dalton dismissing it as "a cramped hippy pad draped in Moroccan rugs and reeking of incense but still failing to conjure anything up beyond superficial mystery." It wasn’t, of course. It was an intense, intricate collage, much like the album’s cover. Epic, consciously overblown but never pretentious, it seemed a towering statement: it showed a mastery of dynamics and drama that adopted the escapist aesthetic of the contemporary shoegaze scene and then stripped it down, bloodily, to a lean, sinuous frame that owed as much to Big Black as it did to Hawkwind, whose 1980 album had given the band their name. But it was also released only a month after Blur’s ‘Popscene’ (and a week before Suede’s ‘The Drowners’) emitted the first screams of the nascent Britpop scene. With the coincident bankruptcy of Rough Trade, Need For Not seemed to have been born out of time.

Listening now, in the light of the twenty years that have passed, it sounds passionate and vital, as indebted to rock’s past as it is predictive of the future. Led Zeppelin and Rush are present in much the same way as they were on Jane’s Addiction’s Ritual De Lo Habitual 18 months earlier, but there are also hints of the textural intricacy of instrumental rock acts like Mogwai, the post-hardcore energy of At The Drive-In and, in Francolini’s drumming, the blueprint for Battle’s precision-tooled battery assault. At the time, there were few acts doing what they were doing: The God Machine, or perhaps Swervedriver, were amongst the only other bands successfully trying to harness the power of metal and pull it in more universal directions. Of course, neither provoked discussion of ‘progressive’ tendencies in the same way, but this should be considered in the light of Bickers’ defence to Melody Maker that, "We’re Progressive. We’re into ideas." Levitation were, after all, no more ‘prog’ than Radiohead were to become: they didn’t want to limit themselves to the orthodox. In fact, it’s hard not to hear similarities in Radiohead’s work released since The Bends. The Oxford band may be less savage in their approach, but there’s a comparable intellectualism in their arrangements and song structures and, in Jonny Greenwood, a guitarist who – like Bickers – seeks to coax unexpected, even outlandish sounds from his instrument.

There was psychedelia buried within the grooves too, a mystical desire to explore the subconscious, the outer realms, the places where other music often feared to tread. Furthermore, the band’s connection with the prevalent counter-culture meant that they were aligned with less obvious contemporaries like The Orb: Bic Hayes, for instance, was associated – via his links with The Cardiacs – to the free festival scene and the new age traveller movement, which had been the victim of heavy crackdowns in the late 1980s thanks to the Conservative Party government. As Mike Smith, the man who signed their publishing – and who was coincidentally recently replaced as head of Sony Columbia Records UK by Alison Donald – said recently, "They had enormous sympathy with the rave scene, and yet you had two incredibly powerful guitar guys up front, so they weren’t a beats driven band. They all were completely in step with everything that was going on with rave, and the whole psychedelic side of acid house, yet none of them really knew how to make that kind of music."

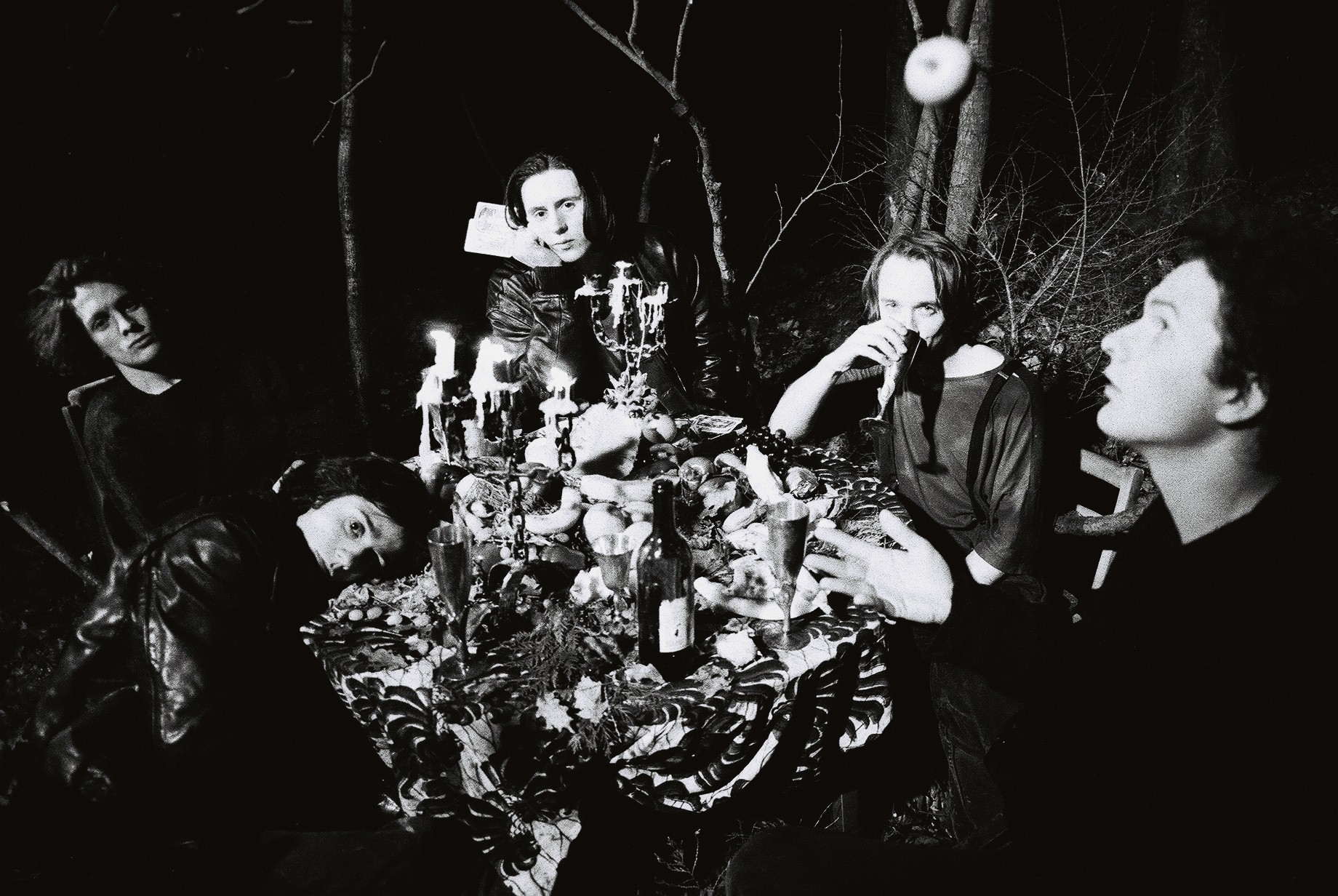

Pinning down Levitation is therefore tough. Each individual brought plenty to the feast and was given freedom to scatter ingredients as they saw fit, so what emerged was often as unpredictable as it was thrilling. Certain qualities ran through it all, though, especially the camaraderie that lay at its heart and the music’s sheer immensity. From the first thunderous chord of ‘Against Nature’ to ‘Coterie”s desperate, exhilarating close, it was committed to translating the grand ambitions of the band into something indestructible, and the sense that they were a gang is evident in the manner in which each member gets his turn in the spotlight without ever hogging it.

The opening salvo of ‘Against Nature’ and ‘World Around’ offer a merciless offensive with Francolini’s drums like ceaseless artillery. ‘Hangnail’ is a sprint into dark, almost gothic territory, Bickers sounding breathless and disorientated as he asks, "What do I feel?" ‘Pieces Of Mary’ detonates its peaceful introductory passage within thirty seconds, the resulting bedlam full of menace, with layer upon layer of guitar effects and keyboards occasionally punctuated by brief, doomed spells of comparative harmony. ‘Resist’ is a little calmer, Francolini’s drums less belligerent, the song’s stabbing piano chords blunted by a dreamier, more anthemic atmosphere. A re-recorded version of ‘Smile’ (originally from their debut EP, Coppelia) maintains a more optimistic composure, a hint at the more commercial direction that their final release and first single for Chrysalis ‘Even When Your Eyes Are Open’, would take. It too, though, heads off into the stratosphere at its climax on the coat tails of guitar squalls, even if the intensity at last gives way to ‘Embedded’, whose slower place – combined with keyboard player Bob White’s simple, repeated melody – makes for a much more morose experience, despite an uplifting, almost blissful conclusion.

Arguably its two most memorable moments are its two longest songs, the sprawling ‘Arcs Of Light And Dew’, which glitters threateningly as though mercury runs through its blood, building towards a stunning, sparkling but terrifying peak, and ‘Coterie’, which finds Bickers at his most free-spirited, emerging from a soundscape that – though he may not wish to admit it – briefly owes a debt to U2’s The Edge. "There are islands and there are children," he sings, never more placid, his voice floating through the ether, and for a while it seems that the maelstrom has finally passed. But, as with the band itself, the final pandemonium is yet to come, signalled by an increasingly frenetic rhythm section and Bickers’ prophetic lines, "Only the human condition could be so out of touch / In the last chaotic way."

And then they were gone. In all honesty, it was intense stuff – probably too intense for the times – but therein lies Need For Not‘s longevity: its dedication, its extremism, and its stubborn refusal to compromise. Compared to what was going on around them – shoegazing, Madchester, grunge and, though still in its infancy, Britpop – this was music that was trying to dig deep into the mind rather than live in denial or simply get out of its head. It was part of an amazing adventure, albeit one destined to end in bitter disappointment, and – even if these days Need For Not lies patiently waiting to be rediscovered by those who have since failed to recall the band’s brief but blinding ascent into largely uncharted space – it was a triumph. The world may not have paid attention, but Levitation were far beyond its reach anyway.

Next week… Bust-ups, breakdowns and bankruptcies, a drive-by shooting and lots and lots of drugs: an oral history of Levitation and the early ’90s indie rock scene…