"I was born like this, I had no choice. I was born with the gift of a golden voice."

He was funny. Who knew?

Everyone who’d been paying attention knew, granted. But they were the minority, and a diminishing one. By 1988, it seemed most of the people one encountered who’d heard of Leonard Cohen hadn’t really heard him. They invoked him as a default punchline for gags about bohemian bedsit misery and slitting your wrists at four in the morning and so on. If they knew any song of his, it wasn’t ‘Hallelujah’, which was then an obscurity buried on an album – Various Positions [1984] – not so much released as furtively abandoned upon the doorstep of oblivion. It was more liable to be ‘Suzanne’; one of those corny, portentous, inane aberrations (see also ‘Imagine’, ‘Blowin’ In The Wind’) which loom disproportionately over the careers of great artists.

Everybody knew Cohen was a great artist. That, as Cohen himself recalled it, is what the boss of his record label told him, when presented with Various Positions. "We know you’re great," said Columbia president Walter Yetnikoff, "but we don’t know if you’re any good." That’s how it goes. Everybody knows.

Cohen is a raconteur, of course, after his own spare fashion; and raconteurs embellish. He is also a poet, and a wit, so one can easily imagine him devising a poetic and witty kiss-off for himself to endure. Even if Yetnikoff used those words, what counted were the ones that followed: Columbia had no use for Various Positions, because it wasn’t "contemporary".

Which is odd, because it did at least have tinges of what was then contemporary – the synthesisers, the production, the vocal treatments – all of which were new to Cohen’s work. So Cohen did what any great artist would do in the face of such rejection. He carried on in the same vein, only more so. For the next four years. If parts of I’m Your Man sound as if they were conceived and executed solo upon a cheap, tinny keyboard by a songwriter better accustomed to six nylon strings, that’s because they were.

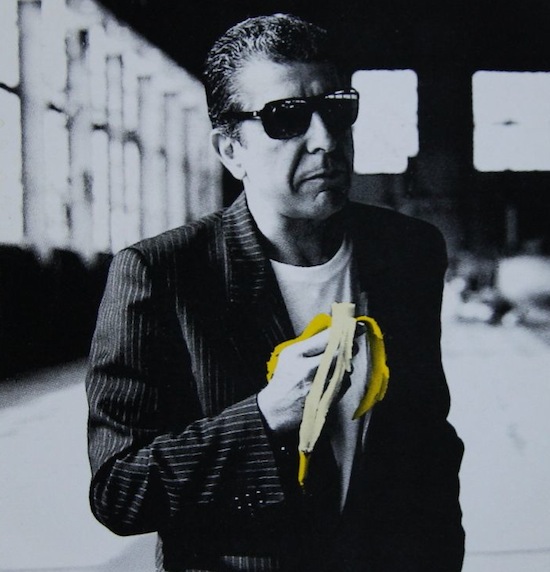

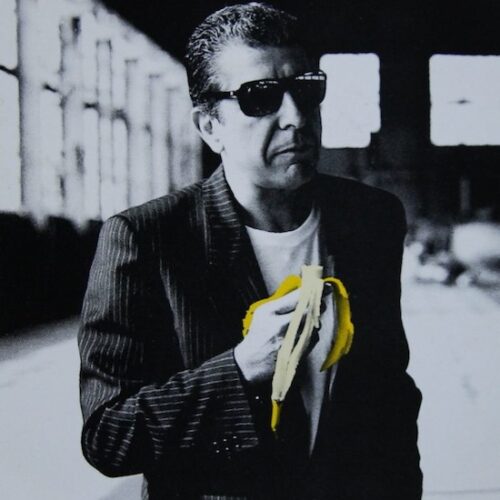

You could hear it as a kind of fuck-you – "You want contemporary? How’s this?" – if that didn’t seem altogether unlike a gesture Cohen would trouble to make. The days of ‘A Singer Must Die’, a sarcastic, petulant rebuke to critics, were far behind him. Cohen pushing forty still felt the stings keenly. Cohen in his fifties was a much more seasoned and amused creature; the Cohen we’re familiar with now. I’m Your Man unveiled him: the roué whose suit and songs were the only sober thing about him replaced by the wry, pinstriped boulevardier – at that instant, less Montparnasse than Sunset. There he stood, double-breasted and sunglassed; bearing a half-unpeeled banana the way a similar-looking figure might (as Cohen biographer Sylvie Simmons observed) have wielded a microphone or a gun. At last, he was tipping the wink. He’d been droll all along, in a mordant way, but now he was a conjuror revealing the hidden gimmick: one need not be comical to be humorous. It is possible – essential, sometimes – to be deeply and deliberately serious in order to be deeply and deliberately funny.

I’m Your Man is both those things, in spades, and through layer upon layer. It wasn’t one of those albums, nor specifically one of those Cohen albums, whose qualities go unrecognised for years. No bushel hid its light. It was greeted with widespread and wholly merited critical joy, outsold any of its predecessors, forced Columbia’s hand in the States (success is always the best revenge), and brought a new generation of fans to a Laughing Len now living up to his ironic nickname.

It was impossible to tell if I’m Your Man was so good despite the toy town production, or because of it. Inevitably, the answer was, "both". It mocked the meat it fed on. It lampooned the glossy, synthetic style of its moment – not the barbed inventiveness of electropop itself, but the airless, formica-coated studio sound of big-time artists struggling to keep up with it – by taking it seriously and using it sincerely. By (in all likelihood inadvertently) exaggerating its superficiality, all the while applying it to a songbook of wondrous depths. Then adorning it with the habitual touches of a lifelong Europhile folkie.

Not until the continuous tour on which Cohen currently remains engaged would we hear those songs as a large and artful band renders them. They were superb then; they are superb now. Like Cohen himself, they are the same characters inhabiting different lives. New skin for the old ceremony, you might justly say. It would be an affectation too far to reproduce them on stage today in their original one-man-and-his-Bontempi-cabaret form. (They were written on a Casio and recorded with an only slightly higher-end Technics; but that was, at times, the effect.) Yet that form is forever inscribed upon them and woven into them. Much as the twin-note solo on Buzzcocks’ ‘Boredom’ stuck up two fingers to the very notion of guitar heroism, so the ungainly plink-plunk instrumental passage on ‘Tower Of Song’ slyly waved at the keyboard wizards of the day the single digit required to perform it.

‘Tower Of Song’… if there’s a keener commentary by any songwriter on his own art, and his own place in it, point me at it. It plods deceptively, a Samurai swordsman disguised as a nondescript tramp. And there’s that "golden voice": no longer a reedy, needy tenor, but a grainy baritone. Was (Not Was), seeking an Isaac Hayes/Barry White vocal turn, would soon ask Cohen to guest on ‘Elvis’s Rolls Royce’. We’d heard that voice before, here and there, but on I’m Your Man it resonates with the accumulated knowledge of Cohen’s middle years – which may fairly be reckoned more knowledgeable than most. He grasps, for instance, the distinction betweens jejune cynicism and weary acknowledgement of the world’s cruelties, which is why ‘Everybody Knows’ pulses with finely tempered disgust: "Everybody knows the deal is rotten/ Old Black Joe’s still pickin’ cotton/For your ribbons and bows/ And everybody knows."

Cohen can sing you to redemption and salvation, the urbane gospel revivalist of ‘Ain’t No Cure For Love’. He can peel back the covers of the heart and deliver it naked and longing, eager to shape itself to the desires of the one it desires itself. If you ever want to know why he’s Leonard Cohen and you’re not, why he has had fascinating and fascinated women throwing themselves under his ever courtly wheels for the better part of eighty years, just listen to the title track. Don’t bother trying to be that man, the one who has answered every other man’s eternal, plaintive question, "What do women want?" by turning it back upon itself and saying to every woman, as if she is the only woman on Earth, "Tell me what you want. I’ll give it to you – whatever the answer, however it changes from one moment to the next." If you knew how to be that man, you would be already. It is, remember, still a song. The man who devised it is Leonard Cohen; the persona who performs it is "Leonard Cohen", the James Bond of suffering artistry. I’m Your Man is packed with truths about life, but this does not require it to be true to life. It is art, all along.

Cohen can do electro-sinister: the cold, ominous throb of ‘First We Take Manhattan’, with its premonitions of the terrorist enemy within, and those Holocaust ghosts intermittently glimpsed, hollow-eyed and skeletal, in the corners of Cohen’s work: "You see that line there, moving through the station? I told you… I was one of those." (Such imagery is never thrown cheaply into a Cohen song. He understands its cost.)

And he can fuck up royally. I believe it was my friend and colleague Andrew Mueller who coined the phrase, "That’s a real ‘Jazz Police’," to describe an inexplicably awful number on an otherwise commendable album. The charitable approach would be to liken Cohen to the maker of a magnificent Persian carpet, who incorporates a flaw, because only God is perfect. The more probable explanation is that he didn’t realise it sucks golf balls through a hosepipe. How profound, how dense, how good is I’m Your Man? So good that ‘Jazz Police’, having smashed into it like a lopsided meteorite, is swallowed up and leaves nary a ripple on the surface after it’s gone. We’re straight into ‘I Can’t Forget’, which is both a pastiche of Johnny Cash doing Kris Kristofferson’s ‘Sunday Morning Coming Down’, and a masterpiece of faux-C&W all the more emotionally honest for its obvious and intentional artificiality.

That makes it one small masterpiece in a larger masterpiece almost entirely composed of them. Given Cohen’s oeuvre, it would be a nonsense to proclaim of any one album that it’s his best. But if you obliged me to choose one and only one to hear again, and again, and again, this would be it. It’s been a companion to me these twenty-five years now and I’ve never so much as begun to tire of its generosity. Many of one’s favourite records come to be friends. This one is more by way of a mentor. Or would be, had I taken on board a fraction of the wisdom it dispenses. (About art in life, remember; not life itself. You can’t live life the "Leonard Cohen" way. Surely not even Leonard Cohen does that.) I’ll give it another twenty-five, if I have them, and see what happens.