Be wary of the curators, including me, and the path they choose for you in ‘building a collection’. Always revealing, those artifacts a dominant culture deems representative of marginal cultures. Reggae music, as an expression of black Jamaican consciousness, as the music that most uniquely summates the imaginative and spiritual desires, and brute reality of Jamaican life, is now usually critically reduced to a half-handful of album-length transmissions.

Noticeable also, among even the ‘collector’ mindset and in the tiny worlds of avant-garde rock-crit and even dance-crit, that increasingly the emphasis on dub’s studio-sorcery or dancehall’s digi-manipulation is paramount. The righteous, the political, the reggae that comes from JA’s vocal and rocksteady traditions is ignored, no-one wanting to sound like they ‘identify’, no-one wanting to be the worse kind of white dread. Understandable as writers increasingly come from a class & time at some far remove from this music’s creation – dub has a universality, a lack of specificity by dint of its instrumental basis and it’s lyric-less suggestiveness, that makes it, in its novelty, curiosity and indeterminacy of focus, way more digestible to ex-colonial nations than albums where the ex-slaves actually stop smoking and speak.

The longer time goes on the more history gets forgotten, and the more things get reduced to a couple of names, interest waning the further we get away from those names’ most emblematic moments. 1976 was undoubtedly an incredible year for dub, the year of Super Ape, King Tubby Meets Rockers Uptown, Joe Gibbs & The Professionals’ State Of Emergency , Burning Spear’s Garvey’s Ghost, Tappa Zukie’s In Dub, Yabby U’s Prophesy Of Dub. But to pluck one album, Super Ape, as most hip curators and critics do, out of that list and make out it’s all you need… it’s criminal oversight for 76 in dub, let alone the rest of Jamaican music. (An awful lot of folk write as if Super Ape & Rockers Uptown are the ONLY dub albums you need full stop).

Perry, as genius, shaman, lunatic, was always going to be as much a star for the music press as Bob Marley, albeit Robert Nesta loomed large as a spirit of organisation and crossover where Perry was the reverse. In 76, one Perry-produced masterpiece made it into the music-press end-of-year-lists, Max Romeo’s fantastic War Inna Babylon (of which more anon): by 1993, NME’s writers could only find space for Augustus Pablo & Burning Spear in their list of the greatest 70s albums.

By 2013, when NME published their list of the 500 greatest albums of all time, two of them were reggae albums and they were both by Bob Marley. This is the way forgetting, driven by class and race, becomes cumulative, drives out the detail, the shades and shadow. Pitchfork’s 70s list has only the Congos’ Heart Of The Congos as the sole representative of Jamaican music. Again and again, what you find is that because white critique is wary, timid and uncomfortable with attempting to understand or interrogate Jamaican music what is clung to as a value is a kind of otherness and oddity, a vanishing into the pure pleasure of sonics to avert any apprehension of the politics or meaning of what black Jamaican people were making. It’s akin to the avoidance of complexity and the reduction to western precepts and expectations (esp. that which is amenable to Western ‘experiment’), in most appraisal of Bollywood music, as I talked about in Eastern Spring.

When I read about 70s Jamaican music, between the lines you sense the further implication is that dub is where heads should be at because the rest of 70s reggae is rather predictable, just as ‘trip hop’ gave the supposed ‘predictability’ of hip hop a ‘spin’ that white-crit could love, without any of that dangerous illiberality of content that made so much 90s hip hop so discomforting. And so, just as if you were listening to trip hop in the 90s and not listening to Wu, Mobb Deep, Black Moon, Show & AG etc you were actually missing out on the trippiest music, so the critical consensus’ desire to reduce reggae to a few figureheads leaves so much out, leaves so much wonder and joy in danger of being forgotten. Whereas hip hop (now it can properly wear the accoutrements of economic power as well as being blessed by dint of coming from the cultural-imperialist stronghold of the US) can reasonably expect to be ‘reflected’ (albeit in a massively withered, reductively mainstream way) in western cultural curatorship, reggae, as the music of poor black people from a tiny island, is mainly ignored completely, its variety distilled into just a handful of ‘things you need’ if you want to render your collection ‘correct’, ticking all equality and diversity boxes. Drives me spare.

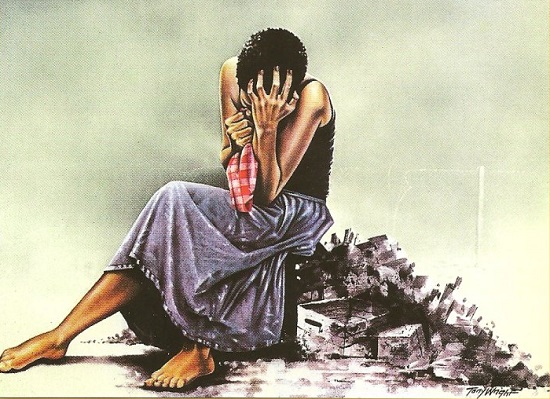

Don’t get me wrong, I fucking love dub, just wish that beyond the Tubby/Perry/Pablo/Scientist lineage usually mentioned, records by Blackbeard, Prince Far I, Mikey Dread, Prince Jammy, Ossie Hibbert, Glen Brown, The Aggrovators would get as much attention as the usual suspects that tick-off dub in the idea of building a canonical collection. Such oversight I can partly put down to constraints of space but I also detect a desire, whenever confronted with a foreign music culture, for western critique to seek that which can be understood in a purely musical, aural context. On one level, dub is stoner music, music made by people experimenting with sound while high as fuck on drugs. Spiritual if you want it to be, and people like Kevin Martin I think truly apprehend dub as a different way of seeing the world. But to sum up Jamaican music, particularly from the year 1976, into Super Ape criminally overlooks the truly important artefacts of that year, three albums with no dubs, deeply lyrical, sweetly recorded, absolutely drenched in harmony and melody and pop, that together form a triumvirate of roots reggae classics and a snapshot of the Island’s turmoil in 76 better than most studio-spun dub confections could manage. The Mighty Diamonds’ Right Time, Max Romeo’s War Inna Babylon and perhaps the greatest masterpiece of all three, The Gladiators’ Trenchtown Mix Up. All three are timeless masterpieces, and like most timeless masterpieces, deeply deeply touched by the times they emerged from.

1976 was a year of blood and fire for Jamaica, a year of civil war, tension, violence, fear and division. The two party system, split between the Jamaican Labour Party and the People’s National Party, had done nothing for Jamaica’s majority black population in the post-independence 60s and was still perceived as tied heavily to old British elites. Both parties operated as multiclass alliances, whose adherents cut across class and racial lines. In their attempt to appeal to all sectors of the population for votes and funds, both parties adopted similar domestic policies (although differences in foreign policy started emerging as soon as the British pulled out). Jamaica’s elites, from which the island’s leaders emerged, were closely knit groups; four of the nation’s first five prime ministers were related. Crucially, party identification, not race or class, was the primary political frame of reference. Each party had a fiercely loyal, almost tribal, inner core defined by family ties and neighbourhood. Antagonism to the other party was passionate and frequently violent.

Between 1972 and 1980 Jamaica’s history of political stability was threatened by a massive increase in political violence. After Norman Manley’s death in 1969, the JLP and PNP evolved along increasingly divergent lines. The JLP started batting for domestic and foreign business interests. Manley’s son Michael, an LSE-educated Third World-oriented social democrat, succeeded him as PNP leader and began to revive the party’s socialist heritage. In 1972 the PNP won 56 percent of the popular vote, thanks in large part to support from the lower classes, including the Rastafarians. Manley had tried to change his party’s image by evoking the memory of Marcus Garvey, using symbols appealing to the Rastafarians, and associating with their leader, Claudius Henry. Manley also had appeared in public with an ornamental "rod of correction" reputedly given him by Haile Selassie I.

Manley’s informal dress and the PNP’s imaginative use of two features of Rastafarian culture – creole dialect and reggae music – in the 1972 campaign were crucial in securing victory. During Manley’s two terms as prime minister up until the bloody mess of the 1980 election, the PNP aligned itself with socialist and "anti-imperialist" forces throughout the world. Manley’s intent was to build a mass party, with the emphasis on political mobilization. He was a populist, keen to engage with the street. Prior to independence, most top leaders had Anglo-European lifestyles and loftily disdained many aspects of Jamaican and West Indian culture. By the 1970s, most Jamaican leaders preferred life-styles that identified them more closely with local culture.

In 1974 Edward Seaga (Boston-born in 1930 to Jamaican parents of Syrian and Scottish origin) had succeeded Hugh Shearer as JLP leader and began a bitter and intense rivalry with Manley. Contrasting sharply with Manley’s oratorical gifts, Seaga was often described as remote and technocratic, though it’s proof of how tribal and party-loyal Jamaican politics is that despite being white and wealthy, he represented Denham Town, one of the poorest and blackest constituencies of West Kingston, which regularly gave 95 percent of its vote to the JLP. The December 1976 elections saw big realignments in class voting for the two parties. Manual labourers, the unemployed, and the Rastas supported the PNP as did the newly-enfranchised 18-21 year olds. White collar voters fled to the JLP, who fought their campaign on building fear about the PNP leading Jamaica into communism (slogans like ‘Turn Them Back’ and ‘The Socialists Have Failed’) while also stoking security fears about the rising number of Cuban immigrants in Jamaica. The middle and upper classes that in 72 had seen Manley as a possible Jamaican JFK now worried he was more like a Jamaican Fidel. Manley’s anti-imperialism and close ties with revolutionary Cuba were exploited by the JLP in the campaign. Seaga played on this particularly, casting himself as ‘freedom leader’ and emphasising the massive economic problems Jamaica had continued to face since 72.

Throughout the 76 campaign you sense divisions were getting harsher, more hysterical – while the JLP tried to play down the class and racial conflicts in Jamaica the PNP emphasised and accentuated them (Manley was a brown man married to a black woman; Seaga was a white man) and you can see the desire to appeal to young reggae culture and reggae listeners throughout both parties’ campaigns.

The increased use of Rastafarian symbols & language by both political parties in the 76 election was a symptom of Rastafarianism’s increasing acceptability and fashionability in Jamaican culture and life. The JLP used Rasta language to promote their political position (modifying the rasta-greeting ‘I-up’ to their own ‘High-Up’ slogan, implying their readiness to govern), the PNP played on ‘Blind-Aga’ to refer to Seaga’s blindness – both parties throughout the 76 election use motifs of slavery to condemn their combatants, and both leaders aimed to reappropriate the legacy of Jamaican rasta-heroes like Marcus Garvey for their cause. (Manley cited Garvey in lots of 76 election-campaign speeches, the JLP reiterating Seaga’s accomplishment in bringing Garvey’s bones back to Jamaica.) The PNP also restated its commitments to supporting contemporary Pan-African liberation struggles such as those then going on in Rhodesia, Zimbabwe, Namibia, Angola and South Africa, asserting that the JLP, a ‘white-man’s party’ had expressed no solidarity with African resistance groups. The JLP de-emphasised race, strategically projecting Seaga as ‘colourless’ although at the Tivoli Sports Field rally that kicked off the JLP 76 campaign he littered his speech with rasta-language. A newspaper report picked up on it:

“Seaga announced the date of the elections and said ‘Them going get a beating’ which was greeted with loud cheers of ‘high-up’… Seaga reportedly said the Prime Minister ‘looks down on the land as his kingdom but I want him to know that Eddie is trodding creation, and the kingdom over which he rules no longer exists because Jah Kingdom Gone To Waste… Youthman and daughter should know which is their party’.”

(The Jamaican Gleaner, 30th November, 1976)

"Them going get a beating" referred to a Peter Tosh, Joe Gibbs-produced smash that the PNP had used in their 72 electioneering; while ‘Jah Kingdom Gone To Waste’ referred to middle-class balladeer Ernie Smith’s 76 hit ‘And As We Fight One Another Fe De Power And De Glory Jah Kingdom Goes To Waste’ – a track used by the JLP throughout their 76 campaign. Rastafarianism was well aware of how its motifs, language, customs, costume and music could be used for political ends – in 76 Bob Marley’s ‘Rat Race’ ("Political violence fill ya city/ Don’t involve Rasta in your say-say"). Also Jacob Miller’s ‘Roman Soldiers Of Babylon’ ("Coming from the North/ with their pockets full of ammunition/ try to turn dreadlocks into politician" – referring to the JLP’s alleged importing of weaponry from the US) warned of politrickal reappropriation. But then one of the biggest rasta-hits of 76, Neville Martin’s ‘The Message’ came out firmly (with ‘heavy manners’) in favour of the PNP.

As the election campaign ensued and grew more and more suffused in gang-related gun-violence and chaos, reggae music and the island’s biggest star couldn’t avoid getting embroiled. The ghettos of Kingston, their shops empty, their infrastructure crumbling and poverty rife, had more guns, more gangs, more shootings than ever – deadly centuries-old enmities between families and tribes playing out under the PNP/JLP conflict in a barrage of block-to-block bloodshed and warfare.

Political arrests and imprisonments, and allegations of foreign arms funnelling from the CIA to the JLP, stoked the fires and resentment. Manley, ostensibly in an attempt to placate warring PNP/JLP factions co-opted Bob Marley’s idea of a free apolitical event, the ‘Smile Jamaica’ concert, and together with Marley set it to take place on December 5 at the National Heroes Park in Kingston. Marley was to headline but on December 3, two days before the event, his wife and his manager Don Taylor were wounded in an assault by three unknown gunmen at their home – an assassination attempt many suspected had political motivations (the Smile Concert was widely suspected as a purely pro-Manley support-rally).

After the PNP won the election the violence subsided briefly, only to return in the ensuing years with a frightening new level of fatality and force. Because Bob Marley is such a massive figure in reggae music and Jamaica’s history, the part he played in the 76 election (undoubtedly the Smile concert helped Manley’s cause, despite Marley’s discomfort with politicians) and the moment he bought Seaga and Manley together to shake hands during the One Love Peace Concert in 78 (his first Jamaican performance since the Smile concert) have become epochal moments in reggae history, proof of the man’s bravery and spirit. Marley is amenable to a version of reggae history that likes the big dramatic moments of sanctimony, the kind of direct messianic reaction and response that Bono and Geldof and others would try and make their own in the subsequent decade.

However, as listeners, if we want to point ourselves towards records that explored precisely the conditions in Jamaica in 1976, we’d do well to avoid such figureheads, frontmen, demagogues. I’d focus more on three albums, two by vocal groups, one by a total eccentric, that for me perfectly encapsulate the myriad tensions, traumas and hopes of that generation of young Jamaicans. The Mighty Diamonds’ Right Time is perhaps 76’s sweetest yet sharpest transmission from the island, thanks in no small part to Donald ‘Tabby’ Shaw’s gorgeous vocals. The aching lilt was forged through the group’s utter adoration of US soul and old doo-wop, and makes Right Time a poignant, deeply moving document of a nation under siege from within, falling apart at the seams.

Formed in the late 60s, the Diamonds as they were originally known, were welders, policemen, soldiers, united by a love of the Manhattans, Stylistics and O’Jays, playing talent shows and gigs, recording first for ska-veterans Rupie Edwards and Stranger Cole on their nascent reggae imprints in the early 70s, hooking up with Bunny Lee and Jah Lloyd (who gets a credit , and finally finding a real home at Channel One and releasing their first hit ‘Shame & Pride’ in 73. Backing vocal work for Lee Scratch Perry also pushed the Diamonds onwards (it’s them providing the b-vox on Susan Cadogan’s ‘Hurt So Good’) – by 74 they’d already started dropping the covers and writing their own material and it’s these self-penned songs that form the bulk of Right Time.

Also crucial to the record’s writing process was the instrumental innovations of session men Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare. Joseph ‘JoJo’ Hoo Kim, who had set up Channel One Records, gave Sly & Robbie the creative freedom to come up with a totally new sound for reggae, Dunbar in particular adding clipped snare sounds, skittering cymbals and double rim-shots to traditional one-drop beats to create the definitive, almost proto-disco roots reggae rockers-rhythm pulse. The run of hits the rechristened Mighty Diamonds scored in 75 and 76 are what makes up most of Right Time and it has that all-killer no-filler tight singles-compilation vibe to it. These are pop songs, exquisitely detailed, beautifully performed, but with a hell of a lot to say – the mellifluity of the vocals only accentuating the depth of the messages. Many people will first hear Right Time as simply a gorgeous suite of pop – when you dig into the words behind those sublime hooks you apprehend this music’s political bite and weary, wary range.

The title track kicks things off in no doubt that these are tough times, men finding themselves with their "back against the wall", the right time the moment when things "go bitter… some a go charge fe treason… fe arson… fe murder", the chorus grimly predicting that "when the law man come, some a go run till dem tumble down/ When the Parson come, him a go quote de scripture/ Swallow Field a go be in a the battlefield". ‘Why Me Black Brother Why’ laments the lawlessness that by 76 was tearing Jamaica apart, the violence towards women, the voice that calls you to "pick up your guns and go to town/ See your black brother and shoot him down". All of this is delivered by Shaw with hugely plaintive effect, a lyrical eye well aware of horror but a singing voice that almost brings hope and defiance to life with every syllable.

Right Time throughout is an irrefutably moral document – it calls sides, it declares truth, it insists on peace, and it wraps up its conscious message within some of the most hypnotically hookiest Jamaican pop music ever. ‘Them Never Love Poor Marcus’ nails those who’d betray and then exploit Garvey’s legacy for their own ends, ‘Gnashing Of Teeth’ rains fire and brimstone down on those unprepared for Armageddon. ‘Go Seek Your Rights’ insists on unity and compassion ("there comes a time in the life of every man/ When you’ve got to face reality" sings Shaw with a falsetto worthy of Smokey) and the utterly stunning ‘I Need A Roof’ laments the housing & poverty crisis faced by Jamaica’s forgotten underclass in a direct way none of the political parties could get close to. When the MDs stop proselytising and simply sing about love the songs (‘Shame And Pride’, ‘Have Mercy’) are no less wonderful – and you can really hear how Shaw’s vocals would influence so many singers, not just in reggae, but in UK pop for the next decade. Throughout, Joe Joe’s Channel One arrangements, Tommy McCook’s tenor-sax and of course, Leroy ‘Horsemouth’ Wallace’s diamond-tight drums seal a masterpiece.

Virgin by now had signed the Mighty Diamonds, initially purely to distribute Right Time abroad. A tour of the UK in 76 allowed the MDs to be seen by fledgling UK groups like Aswad and Steel Pulse proving massively inspirational to the growing UK homegrown reggae scene. Alongside fellow traveller U-Roy they dodged thrown tomatoes and eggs at the 76 Reading Festival – soon however, Virgin attempted to take Mighty Diamonds away from their Channel One base, forcing them to record in New Orleans, and then at Compass Point in the Bahamas in order to eliminate Channel One from the picture altogether, and keep that money flowing into Virgin’s coffers alone. The music that resulted suffered from this typically British attempt to realign original black music closer to more dependable and traditional modes of production but 40 years on Right Time should recover its place as a roots-reggae classic, absolutely essential to any understanding of the political, lyrical and musical complexities of mid-70s Jamaican culture. If you don’t know, get to know.

The PNP had used Max Romeo’s music in the 1972 election, namely his ‘Let The Power Fall’ track from his PNP-boosting 71 album of the same name. Romeo, like many reggae artists had moved from rural poverty to urban struggle in his youth and after 10 years of post-independence rule by the conservative JLP was firmly in support of Manley and the PNP in 72. He’d certainly not started as a firebrand – his early notoriety, especially in the UK, rested on his breakthrough hit, 1968’s ‘Wet Dream’. Despite Romeo’s rather lame claims that it was about a leaky roof, lines like ‘Give the crumpet to Big Foot Joe/ give the fanny to me’ left most broadcasters in no doubt as to its lyrical intent, the BBC playing it twice by accident before instructing Radio 1 DJs to only refer to the song when doing chart rundowns as ‘a record by Max Romeo’ (interviewed in 2007 Romeo admitted that the ‘devil made me write it’ before insisting that he ‘single-handedly started the sexual revolution’).

After the PNP’s victory in 72 he released ‘No Joshua No’, an open musical letter to Manley (usually referred to by his nickname Joshua by supporters) and a plea to not forget the poor, that depending on who you believe, actually influenced Manley’s programmes of social reform. The political disappointments of that first Manley administration drove Romeo back to his gospel and devotional roots – by 75, still firmly ensconced with long-time associate and former employer Lee Perry, albums like Revelation Time collated Romeo’s dread-gospel singles he’d recorded with a variety of producers. It was only a matter of time though before Romeo’s agit-prop sense would be reanimated.

The 76 election was conducted under an air of economic bedlam for Jamaica – IMF interference, oil embargoes and worldwide recession only fanning the flames of anger and riotous despair. As JLP agitators attempted to make the island ungovernable (check out Marlon James’ utterly compelling A Brief History Of Seven Killings for a scintillating Ellroy-esque narrative about Jamaica’s 1976 intrigues and incursions), Romeo, like the Diamonds, released a stunning set of singles that returned him to political commentary with acute and timely effect.

‘Sipple Out Deh’ (originally called ‘Dread Out There’ but changed under Scratch’s suggestion that ‘Sipple’ – i.e. slippery – would be a better word) in its original 7” Jamaican incarnation is a FEVERISH record, simmering with heat, flickering with tension. It impressed Island Records’ boss Chris Blackwell so much that he commissioned Scratch to record an entire album’s worth of material from Romeo, including his other 1975 singles like the mournfully bleak ‘One Step Forward’ and stepper classic ‘Chase The Devil’ (as sampled by the Prodigy on ‘Out Of Space’ and by Kanye for Jay-Z’s ‘Lucifer’). Often, re-recordings for Western labels deodorize the unmannered into the palatable (and I still prefer the original version of ‘Sipple Out Deh’) but Scratch’s production work on War Inna Babylon, the album that emerged, is I think perhaps the highpoint of his career, the perfect mix between Black Ark’s unshakeable swampiness, ravishing state-of-the-art production and world-dominating hooks. ‘One Step Forward’ sees the Upsetters announce themselves, one of the tightest, sharpest, loosest, most sublimely hypnotic bands in history – Romeo’s lyrics ratcheting up the sense of 76’s suspicion and impending doom –

”One day, you are dreadlocks

Well dread, next day you are ballin’ cliche

Are you a commercialized, grabbing at the cash-backs?

This is a time of decision – tell me, what is your plan?

Straight is the road that leads to destruction

The road to righteousness is narrow

Vindictive feelings enter feeling, the truth is a fact

tell me are you a con man or are you a dreadlocks?”

No accident that Romeo’s words would find such echo in the UK in 76, a country also going through its own political turmoil, although the reviews at the time tread an uneasy line between praise and wariness of full solidarity with such a foreign culture. Mick Farren in the NME mixed acclaim with a queasy sense of his own cultural baggage:

“…one of the hardest records in that particular combination of spiritual/social that makes up West Indian new politics, to come out of JA in a while. And that’s precisely why I find it impossible to write about it. You think that’s a copout? Okay, but I don’t see how any white boy can really write about this kind of overt militant reggae. It doesn’t matter how good a crusading radical you are, how many dubs you got in your collection, how much herb you get through or how many of your best friends are n*ggers. Your background is Babylon, your upbringing is Babylon, and you yourself are a tiny piece of Babylon. We don’t see the thing through the same eyes. That doesn’t mean you can’t get off, though. The learning process is, after all, designed simply to get you further.”

(NME review, June 1976)

The gorgeous ‘Uptown Babies’ takes snapshots of kids in the street, selling papers and ice-creams before skewering the reasons for such industriousness – hunger, poverty, the fear that happens when a walk down the street means strolling through a war-zone.

“Uptown babies don’t cry they don’t know what hungry is like

they don’t know what suffering is like

they have mummy and daddy, lots of toys to play with

nanny and granny, lots of friends to stay with”

Despite Farren’s doubts, I doubt anyone human couldn’t have their hearts broken by this song, and underneath the hooks and heartache there’s Marcia Griffith’s beautiful b-vox and the Upsetters always on point, rotating like Can, staying put on the groove like no-one else. Despite familiarity, ‘Chase The Devil’ is still just mighty, and the title track takes ‘Sipple Out Deh’ and focuses it, lets the song grow from its island-origin until it takes on a global weight and focus.

First time I owned the album on vinyl I simply couldn’t get past this first side, so perfect is it, so brilliantly controlled are Scratch’s production touches, the phased hi-hats and kick-drum drop-outs, his genius marshalling of all this wonder. Once I had got over that addiction and flipped it the 2nd side revealed even more glories – ‘Norman’ and its glittering neon depiction of aspiration, greed and high-rolling criminality (with some of Scratch’s most brilliant musical ideas, the flute and piano in particular); the meta-gospel of ‘Stealin’ and its incisive spearing of religious hypocrisy; the stealth and suggestiveness of ‘Tan And See’; the weed-infused dance-anthem ‘Smokey Room’ (that psych-flute back and banging) and the closer ‘Smile Out Of Style’ seeing things out in a mood that tightropes both anger and resignation. ("Smile out of style/ laugh on the wars you face back in town/ don’t blame the children/ blame the teachers.")

War Inna Babylon is often seen, before the Heptone’s superb Party Time and Junior Murvin’s Police And Thieves (both from the following year, 1977) as the first part of Scratch’s ‘Black Ark Holy Trinity’. I see it, and still hear it, as superior to both and, like Right Time an album absolutely essential to understand where Jamaican music was at in 76 and where it had been until 76. Crucially you can’t just hear Jamaica’s problems in the album’s grooves and words – you can hear a whole world of havoc being reflected, resisted, raged against. It still sounds accurate to anywhere that people are getting destroyed by their rulers, hence its feel of sharp timeliness right now in the UK. If it’s not in your racks, you’re simply bereft. Own it as soon as you can.

Where War Inna Babylon, because of Scratch’s presence, still registers peripherally in some curators overviews of the era The Gladiators’ Trenchtown Mix Up, like Right Time seems to have entirely slipped off the radar. Like the Diamonds, the Gladiators had been going for a decade before their greatest album was created. Like the Diamonds, the Gladiators were a pop group who were entirely fearless of addressing the political realities of 1976, shifting their lyrical content to address the contemporary chaos. The vocal trio had met on a building site in 1967 where they were all working as masons, a building site in Washington Gardens right next to Lee Perry’s house (another mason onsite, incidentally, was Nicky ‘Love Of The Common People’ Thomas, another two were Stephen Taylor and Leonard Dillon who’d go on to score hits as The Ethiopians starting with ‘Train To Skaville’ in 67).

The fledgling Gladiators, led by singer and guitarist Albert Griffiths, moved from singing while they worked to getting studio time together at Coxson’s hitmaking factory at Studio One, scoring a hit with ‘Hello Carol’ in 68, staying at number one in the JA charts for 7 weeks. The Gladiators went on to have a steady run of hits from 68-75 with Studio One, their singles so damn hot record shops wouldn’t allow punters to buy a copy unless they bought another less-desirable single alongside it (a common money-hungry tactic). It was the Gladiators’ hooking up with the shadowy, part-legendary figure of ‘Prince’ Tony Robinson that led to the creation of Trenchtown Mix Up, essentially a collection of re-rubbed old hits and new songs for 76, picked up and released by Virgin. Robinson wasn’t just a producer, he managed the Gladiators with a hustler’s energy, encouraging the band to cut covers of old Wailers tunes much to Griffith’s anger (“He wanted us to be imitators not originators” said Griffiths in a 78 NME interview with Penny Reel – their corking and caustic 77 hit ‘Pocket Money’ is directly about Robinson).

Trenchtown Mix Up works precisely because it is a mix up of the band’s history and their response to the febrile 76 present, but a mix-up in which you can’t see the joins, in which everything flows together as if written in the same moment. The old songs sound mighty thanks to Robinson’s smart incorporation of additional bassist Lloyd Parks and drummer Sly Dunbar into the set-up during recording at Joe Gibbs’ studio. The new clarity of recording brought to those old numbers brings out the unique call and response nature of the Gladiators vocals, what guitarist Clinton Fearon called a ‘question-and-answer’ harmony, very reminiscent of gospel, making each song a process of steady revelation, an almost Baptist-like back’n forth of exquisite falsetto, faintly dubbed by Robinson in all the right places.

The Marley-covers Robinson insisted upon are superb and to this listener entirely eclipse the originals – ‘Soul Rebel’ exploding with a murderous thump and ‘Rude Boy Ska’ seeing the album out on a singalong riot of dancefloor-directed celebration. So far, so great but it’s the new songs written by Griffiths specifically for the album that elevate Trenchtown Mix Up to something beyond, that for me make it the most solid stone-cold masterpiece JA gave us in 76. Griffiths was always a unique songwriter, mystic, metaphorical, stringing parables together with proverbs and folkloric phrases. In his original songs for Mix Up he doesn’t target specifics, name names, or didactically push a political agenda, rather he paints a picture of a society riven with suspicion, rumour, gossip, backchat – a society quick to judge, a society of lawlessness where order has been derelicted by the state and only unity can bring salvation, a unity that takes on the utopian aura of heaven, a utopia you know Griffiths can’t entirely believe in. It’s the documentarian eye and the poetic pen of Griffiths that drives the best songs.

Already, on the album’s opener, ‘Mix Up’, a searingly hot recut of their ‘Bongo Red’ single from 74, Griffiths kicks the whole album off with the beautifully balanced and hesitant line: ”I-man don’t like to get mix up/ By pushing me mouth in something I can’t prove." The track really a journey with Griffiths as he walks out of his house and down the street as we see what he sees: “So I take a walk from 6th street… trying to prove something, going to the bottom of 8th street and from corner to corner you can hear the youth dem a shout." And all the while Dunbar and Parks turning up the heat, letting that hair-trigger-tension build. On ‘Bellyful’ Griffiths sees the rice that won’t fill him up, the fires that can’t be put out, the prey-birds battling in the forest, all as indicative of irresolvable conflict, all as portents of an impending ‘bangarang’, chaos, disorder, bedlam: “Then everyone will see, who a de Gorgon/ An’ everyone will see, who a de hero/ For when the rice won’t swell man belly nah go full."

There’s no sunshine in the Gladiators’ darkest songs, they’re nighttime entities, weakly lit, minor-keys throughout – Griffiths, Fearon and bassist Dallimore Sutherland making the rumbling undertow remorseless, ominous, thick with fear, side-eyes scanning the edges. ‘Looks Is Deceiving’ sees Griffiths’ announcing his method before the song starts (“It gwine red down here in Babylon/ so let me give it to ya in a parable”) – the track unfolding as a series of proverbs (“Goat never know the use of him tail till the butcher cut it off”) that coalesce into an ‘ornery message warning against judgement. Throughout the album the songs are allowed to breath, the moments where the three voices step off and the band are just allowed to swim in the smoking grooves they’re cooking up providing perfect counterpoint to the lyrical density and heaviness.

The retro-rocksteady of ‘Chatty Chatty Mouth’ appears to nail political blowhards from both sides of the spectrum (“Your boss is a warrior/ Chatty mouth you are a traitor/ You both belittle the humble/ also fight against the meek”) while promising holy vengeance, always delivered in sweet hooks and cadences. It’s that balance, the metaphorical harshness of the words coupled with the sheer melodic bliss of the harmonies, that makes Trenchtown Mix Up such an instant joy and so slow-burning in its revelatory impact. ‘Eli Eli’ (a hook based on Christ’s lamentations from the cross "Eli Eli Lama Sabachthani") is perhaps the most melodic song here, a song in which you’ll bust a gut trying to match Griffiths’ vocals, a song whose plea for unity takes on extra weight and poignancy when you realise it’s a plea issued in the midst of the cataclysms of 76:

“We all are one brothers, we all are one sisters

we all are one blood so let’s talk about love and forget envity

if Jah can forgive us then why can’t we forgive one another?”

The centrepiece of the whole album and the track that for this listener is perhaps the greatest of all reggae music in 1976 is ‘Hearsay’. Listen to the first 12 seconds of it. Pure doomsday. A drum fill that sounds like a drawing of shattered breath before this juggernaut of a groove trundles out over your skull and then here’s Griffiths, sidling up, right in your ear, delivering a menacing take-down of shit-stirrers and liars as Sly chops and punches the anger out of his system and out onto his kit.

“Remember this little saying that ‘bush have ears’

pick sense out of nonsense you’ll get the answer

Bush don’t have ears my friend but someone may be in it”

And here the band really clamp down, grab your lapels, push you against the wall, Griffiths almost snarling in your face:

“hearing what you have said about your brothers

hearing what you have said about your sisters

hearing how you have made your own confession

hearing what you have done in the past/ for every secret sin must reveal”

The repeated ‘hearing’ lines make you feel like you’ve been watched, like you’ve been found out, nowhere to run to nowhere to hide – before Griffiths deals the killer blow: “so if you don’t know what a gwan/ keep your mouth shut and don’t say a word y’all’. Between the word ‘gwan’ and the word ‘keep’ he slips in a little falsetto ‘oooh yeah’ that makes that last line drop with planet-sized heaviness. There’s nothing quite as dread, as scalpel-sharp, as heavy and hard-hitting as ‘Hearsay’ in ANY music from 76. It’s a track that grabbed me the moment I heard it, that still charges the synapses with vigilance, sounds the crack of doom every time I’ve heard it since. After ‘Hearsay’ the album issues two last pleas amidst the old songs and covers, ‘Know Yourself Mankind’ takes a look around and breaks it down simply over more mournful minor-keys:

“Our beautiful country have turned into battlefield

Ev’ry day, yeah, is rumours of war

Remember what Marcus have said

Man a go know themselves, when dem back is against the wall

This is 1976

we don’t want no more war”

‘Thief In The Night’ sounds almost-vintage, a rocksteady ballad-cum-lullaby that tucks you in and hopes you can forget the nightmares of wakefulness, Griffiths again walking a lyrical line somewhere between mystic visionary and apocalyptic prophet: “the time is near… can’t you see that his hand is writing upon the wall… you shall see signs and wonders… two shall be let sleeping and one, one shall be taken away… but small as a flea is in a oppressor colla… watch and pray for I shall come like a thief in the night." And even before the album has faded out you’re flipping it over and putting it on again. And again. And again. Trenchtown Mix Up is one of the most unjustly forgotten, totally addictive albums JA ever gave us. Remedy its absence from your life, if it is absent from your life, immediately.

There was a brief respite in the violence after Manley and the PNP won the 76 election. Soon after though economic and social conditions, and the ongoing vicious enmity between PNP and JLP combatants saw Jamaica once again returned to a cycle of violence and hatred that reached its apotheosis in the even-more bloodstained 1980 election campaign. For those that rose and survived through 76 the harvest was a bitter one. Throughout reggae history you are confronted repeatedly by the brute fact that the genii who made so much incredible music from such a tiny island were left frequently unrewarded, fucked over by record companies both here and there, ignored in reissue campaigns, unpaid by reissue labels, even as those labels were supposedly set up by and catered for reggae aficionados.

In 76, the Mighty Diamonds, The Gladiators and Max Romeo all delivered their finest work and were then confronted with the real choice of leaving, or staying. The Diamonds’ attempts at global appeal were mismanaged by Virgin, Max Romeo had a giant falling-out with Scratch and never recaptured his 76 heights, the Gladiators responded to Tony Robinson’s attempts to make them crossover by digging their heels in and staying put. Reggae of course would continue to exert a massive influence over black british music but interest in it from pop’s official curators has waned the further we get away from those figureheads the narrative finds so easy to process – because the rock-critical narrative over here is that reggae is essentially homogenous, it’s become acceptable to kick it safely into touch with a few necessary documents.

I can only suggest that these three 40 year old albums should be remembered in 2016, and strongly advise you follow the trails all three of these masterpieces leave in their wake, both in Jamaica but also in London, Bristol, Birmingham, Coventry – they represent what for many of us, who were introduced to this music via friends, big sisters, big brothers, blues and sound systems, remains a high point in Jamaican music, a zenith of political incisiveness, of playing, of poetry, a zenith of beauty in reggae music. Let’s mark those anniversaries that matter, that still make you feel and think and shake your perceptions and suggest further exploration, rather than those canonical dead texts that shut down that exploration, that safely summate an era for the purposes of filing and ordering. Just two reggae albums in the best 500 ever made? What Jamaica was creating in 76 should be seen as a high flashpoint in 70s music, not a footnote, as important and influential as punk, as disco, as hip hop. We’ve got war in babylon right fuckin’ now. The right time to mix it up again.