“That’s what I’ve chosen for the soundtrack to this landscape. It’s not expected.”

Steve Coogan – The Trip

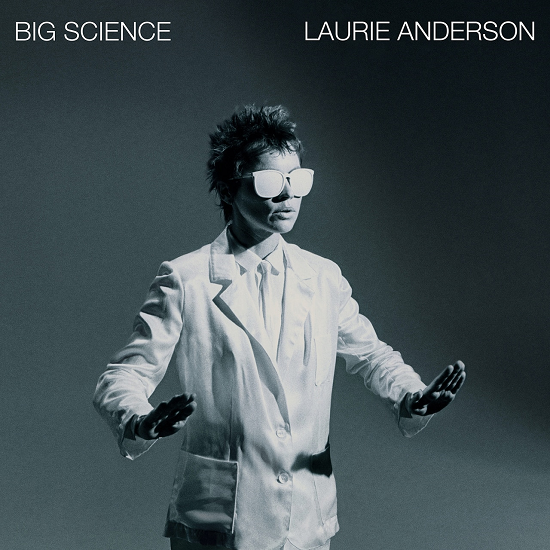

A creative misreading would be one thing, but my teenage belief that Laurie Anderson was a West Country folk singer was plain stupid. That Anderson – the white suited performance artist, the surprise ‘O Superman’ hit-maker, the Lady Galadriel of Times Square – could be mistakenly associated with my environment of scones, hedgerows, violent fights after closing time and horse crap, looks less like a wilful detournement and more like ignorance, yet there is Big Science. An album that, for me and me alone, is as incontrovertibly tied up in the atmosphere and landscape of my West Devon adolescence as drinking cider on a viaduct and listening to Reef’s ‘Place Your Hands’.

That this misunderstanding came to be is down to flimsy happenstance. An older friend made me a tape with Big Science on one side and Nick Drake’s Five Leaves Left on the other. That was enough to get me started, but a throwaway comment from said friend along the lines of “she was great when I saw her live”, conjured the image of Laurie Anderson, who I’d never even seen a picture of at this point, playing in a local pub, wreathed in cigarette smoke with her finger jammed in her ear, surrounded by sagely nodding men in itchy looking jumpers, rather than filming a mah-jong game or playing a violin that’s on fire, or whatever it was that sophisticatedly esoteric New York artists were doing at that point in the ‘90s. That this misunderstanding persisted throughout my first listens to what I now consider my favourite album is even less excusable. Is there a less West Country-centric work of art than Big Science? Reservoir Dogs, maybe? La bohème? Certainly the first looped gasps of vocoder that open ‘From The Air’ should have kicked the notion into touch – back then the vocoder was probably considered by UK folk artists to be the work of Ol’ Scratch – yet it’s a testament to my iron-willed ignorance and youthful intractability that my way of experiencing this album has remained pretty much the same ever since. And that whenever I hear Big Science I’m still a teenager lost on the moors.

Although, looking back, the fact that Laurie Anderson had as much connection to the Devonshire landscape as she did to that of Pluto is obvious – the accent should have been a giveaway – the connections became clearer and have evolved with me as time has gone on. “Every man for himself”, “Yodelayheehoo” wasn’t I basically living in a barely technologized Wild West? Against that backdrop Anderson’s stories of characters facing the disintegration of the old frontiers felt relevant, while still having an enthralling patina of the alien. The stately violin of ‘Born, Never Asked’ – Violin! Folk instrument! – was neon through the mist, the sight of the headlights cutting through the murk of the moors seen from my bedroom window. A journey in the big dark. What does the digital wolf howl at the beginning of the title track mean to someone growing up down the road from where The Hound Of The Baskervilles was set? Not much, maybe. But enough to infuse the act of listening with awkward vitality, to make it creative and tricky and to put the person listening in thrillingly close contact with America’s frightening, bright new world. To this day when I hear the title track I think of walking the road out of Rumleigh, back past my friend Henry’s house, but the hedgerows are studded with neon lights. The sky glittering like a casino. I don’t know if that’s something I ever actually saw, but it’s real to me. A landscape forced into life by Anderson’s escalating streaks of analogue synthesiser and cool narration. As much a part of my youth as watching The A-Team on a Saturday afternoon.

It’s unhealthy, I think, this current focus on the streamlined musical experience. Music as the perfect soundtrack, to be slotted neatly alongside whatever you happen to be doing with your day – running, studying, falconry, whatever. The drive toward neat integration and uninterrupted experience that relegates the messy interference of art in the world to a by-product. That constant cricket-like chirrup you can hear is the sound of a million million ambient albums being cast into the ethersphere. Their soothing burble the perfect accompaniment to baking, or reproducing, or looking for something else to have on in the background while you bake and reproduce. The music and the landscapes of our lives become unimportant reflections of each other, united only by the need for uninterrupted and unchallenged ‘experience’. Listening to Greatest Hits Radio while driving is like constantly existing in the final scene of Pretty Woman. 24-hour-long moments of shiny-toothed triumph, every hour, all hours. Unchallenging and wearying. The crumples ironed out, the mess un-reflected. It is what we have been told works and so we do it.

Big Science can’t hold itself steadily enough to exist that way. Despite its cool, monochromatic presentation there’s a lop-sidedness to its gait as it shuffles from track to track. From monologues to tinkling synthesisers to babies crying. There’s an audible ‘something’ missing from Big Science. I had no experience of United States I-IV, the performance that the songs were originally written to be part of, but here in a fresh context they were free to start blending into their new surroundings – my surroundings – and to start exerting the pull that would twist them into strange new shapes.

That this outside influence mirrors the changes described in the album doesn’t feel accidental. Big Science is, as much as anything else, a picture of a landscape in flux:

“Go straight past where they’re going to put in the freeway/ take a left at what’s going to be the new sports centre/ and keep going until you hit the place where they’re thinking of building that drive-in bank/you can’t miss it/and I said/this must be the place”

In a series of distorted reflections in keeping with Big Science’s glassy projected exterior, Anderson’s songs, written thousands of miles away, were warping my landscape as obviously as the confluence of capitalism and technology was turning her old wild United States into a strip mall. As obviously as the constant reruns of American soap operas and MacGyver-esque action trash were shaping the imaginative world around me, in a town thousands of miles away from where Laurie Anderson wrote the songs that were warping my landscape.

Looked at from this collapsed perspective the idea of Big Science as a folk album isn’t a stretch. The influence of technology, money and greed on communities and environments has always been part of the genre’s vernacular. My opinions might have changed a bit – 14-year-old Mat would’ve given his right nut for a strip mall to magically appear in his hometown – but that constant engagement with Big Science, with what it’s saying to me now, has never changed. Big Science, more than any other album I can think of, and despite its rooting in a vividly evocated time and place – the 1980s, New York, Reagan’s America – has always rewarded misinterpretation and misunderstanding. An approach that pulls the listener away from mediated, holistic ‘experience’, and toward new combinations of texture and emotional truth. Parts of my life breathe through the holes in this album. It is an exoskeleton of constantly shifting concern. From “why am I so sad?” to “why do people hate each other?” to “are we all going to die?” The big worries of life and the folk who have to live it. An electronic howl from the dark of the moors.

“This is the time/and this is the record of the time”, Anderson announces on ‘From The Air’. Big Science, more than any other record I can name, is always the time and the record of the time, no matter what or where that time might be.