Somewhere on the banks of the Hudson River, Mr & Mrs.Houdini are locked in an embrace. (Or so Hollywood would have us believe.) Mr. Houdini, master of escape, is in shackles & about to plunge the depths, unbeknownst to him, for the last time. Resting on her tongue, Mrs Houdini has a key which she will pass to him as they kiss. It will, she hopes, set him free. With eyes languid and alert, resplendent in Houndstooth jacket and impeccably coiffured auburn hair, the wife, it has to be said, is a foxy dame. If her husband fails to break loose and dies, he promises that he will contact her from the dead. To ensure the medium is no fake the couple have a code: ‘Rosabel, believe’.

Many years later, 1981-82 to be exact, Kate Bush in various recording facilities across London, is enacting her own daredevil feats, devising her own codes, making music of such soul-searching intensity, it often locks the listener in its own embrace. Unlike Harry, the Bexleyheath-born singer will emerge

unscathed, a little bruised by the quizzical reaction her magic has received. But she has broken free of pop stardom’s strait-jacket, to infiltrate the ranks of art-rock aristocrats.

"Fresh air after punk’s foul blast. The suburbs breathed again," so wrote barmy biographer Fred Vermorel regarding Kate Bush’s appearance on the music scene in 1978. Under the aegis of David Gilmour of Pink Floyd, who funded early demos, Bush secured a record deal with EMI in July 1976. Before releasing a note of music, however, she studied movement with Bowie’s mime instructor Lindsay Kemp and honed her song-writing skills, dipping into a vast backlog of compositions, worked on ever since her father showed her the middle C on the home piano. By the time of ‘Wuthering Heights’ in January 1978, she arrived fully formed.

‘The company’s daughter’ and the most photographed woman in England. Keef Macmillan’s s pic of her in a pink leotard (a source of ire for the family) paraded on double decker buses everywhere. Bush was an overnight sensation. The rush of superlatives in both song and interview & her distinctive singing style, all provided ammunition to parodists and hostile critics. With her four-octave range, terpischorean piano balladry and the lace & chintz wordplay, full of references to Gurdjieff and Victorian literature, the Welling-raised, convent grammar school-educated prodigy, stood in stark contrast to the zeitgeist. The new wave was spinning in various directions, either down the drain (the Pistols split that very year), down a nihilistic dead end or into the outer limits of post-punk.

A gauzy reverie amid such musical violence, Bush’s first two albums, The Kick Inside & Lionheart (1978) are suffused with Albion romanticism and boudoir ruminations. But pierce the patina of AOR production gloss and musty madrigals, subversion trickles out: incest, murder, carnality, homosexual frankness (‘Kashka From Baghdad’ was deemed suitable for Ask Aspel, a children’s show, the pat on the bum during the video for ‘Wow’ was censored). Raised on traditional folk song, music with a strong narrative thread and a heavy undertow to its lilt (The Kick Inside’s title track was inspired by Lucy Wan), Bush was adept at sneaking naughtiness in through the backdoor. Second single ‘The Man With The Child In His Eyes’ quickly dispelled any notion of gimmicky kookiness, its Laurel Canyon candour establishing a songwriter par excellence. On the first two albums, an almost obscene sensuality and unerring musicality buoys even the most precious moments of whimsy ("I see myself on the piano as a melody," she sang on Lionheart’s ‘Symphony In Blue’). Schoolboys and Stalinist NME hacks like Danny Baker blushed.

In 1979, Bush undertook her sole tour, an extravaganza that developed Bowie’s use of headset microphones & theatrical presentation. Universally acclaimed, by everyone save Charles Shaar Murray, it was further proof that Bush’s talents were genuine and had nothing to do with studio-bound trickery as some ne’er do wells suggested. At the eleventh hour, lighting engineer Bill Duffield suffered a fatal accident that nearly nixed the tour and put Bush off from repeating the exercise ever again. At a benefit for him, Bush met Peter Gabriel, the erstwhile Genesis

frontman, still carving a niche himself as a solo performer. A fortunate encounter, Gabriel would be a significant source of inspiration for Bush , the man thanked on her third album, Never For Ever (1980) for "opening the windows".

Despite her achievements, the singer herself almost immediately felt frustrated by her musical vocabulary. By Lionheart she was expressing a desire to become ‘more of a rock singer’. Such ambitions remained inchoate. That album’s ‘Don’t Push Your Foot On The Heartbreak’ may have been an attempt to "write a Patti Smith song" but it clashes with the ‘buttons and bows’ of Andrew Powell’s production. Bush sounds shrill and a little unconvincing, briefly making sense of Dave Marsh’s cruel Smith-Hoover comparisons (it fared better in performance). She had her ardent followers. Those with open ears included Melody Maker’s Harry Doherty, Zig Zag’s Kris Needs & Sounds’ Phil Sutcliffe. The latter observed shrewdly that "if she has genius within her, it will not escape unemployed". Bush’s transformation into the artist she aspired to be, would be a little agonizing but monumental.

Session work on Gabriel’s epochal third album (aka Melt) gave Bush the signpost she was in pursuit of. Gabriel’s own final flight from the shadows of his past was aided by the Fairlight CMI and the rhythm box (in his case, the PAIA). The CMI was a sampling synthesizer, very much in its infancy (only invented in 1979). Both devices had a seismic impact on Bush’s methodology. They facilitated a move away from piano-based compositions to a more layered, experimental approach, where rhythm shaped much of the music’s spine.

As synthesizers became more portable and affordable, a form of electronic skiffle ushered in the new decade. Concurrently, the Fairlight was both an innovation and a throwback to the bulky, big budget prototypes of yore. Halfway through recording her third album Never For Ever with co-producer Jon Kelly, Richard Burgess & John Walters of electro absurdists Landscape, demonstrated the gadget’s opportunities to her. As the singer seized control of her music, the machine wasn’t just a textural boon, it enabled her to oversee all components in a musical arrangement: an invaluable tool for any musical auteur/collagist. Crucially it ‘sampled’ from the natural world Bush’s work drew such inspiration from.

She was also enamoured with the colossal ‘gated reverb’ drum patterns, without cymbals, Gabriel was cultivating with engineer Hugh Padgham at London’s Townhouse Studios. As with the Fairlight, this would become a salient feature of 80’s rock, perhaps most associated with Phil Collins’ In The Air Tonight (1981). Collins had learned the technique while working on Gabriel’s Melt album and had gone as far as recruiting the singer’s producer, Hugh Padgham. This suggests a kind of forward thinking MOR phalanx during this period. At the time only Tony

Visconti’s pioneering work on Bowie’s Low (1977) was this drum sound’s only real precedent. (Visconti was briefly considered for production duties on The Dreaming before Bush assumed full responsibility).

Discussions on post punk tend to focus on the myriad possibilities up and coming bands were negotiating as punk’s narrow rule book was torn up and rewritten. However, it was equally galvanic to the more maverick pre-punk vanguard. Stateside, the most famous example of this was Fleetwood Mac’s

Tusk (1979), a ‘career suicide’ double that managed to incorporate a lo-fi rumble into its sprawling four sides while never remaining slavishly deferential to the dogmas of 76. Spiky, outré hybrids abounded, often from the most implausible sources. Daryl Hall’s Sacred Songs was considered part of a trilogy with collaborator Robert Fripp’s other works, Exposure and Peter Gabriel II (aka Scratch). It was this bizarre mix of angular musical anarchy with pre-punk muso chops that Gabriel typified on III. When reviewing a somewhat similar record, Bowie’s Lodger, Jon Savage coined the term ‘avant-AOR’. It is perhaps this tag that best describes the kind of music Bush would go on to construct.

In tandem with this plunge into mixing desk magic was a more overt topicality in Bush’s writing. 1980’s ‘Breathing’ signalled a new era for Bush (it got her on Nationwide). The song, written from the viewpoint of a foetus reluctant to be born into an apocalyptic world, was a quantum leap from the windy, wiley moors of Bronte. Equally startling was the record’s sound, she referred to it at the time as her "little symphony" and it marshalled an album’s worth of scope into its duration. Bush’s melodramatic ivory tinkling is woven into a throbbing musical backdrop. Gabriel’s trusty synth wizard Larry Fast on Prophet

5, the ‘atomic instrumentation’ of Pink Floyd’s The Wall (side 3 apparently, ‘Hey You’ in particular) and 10cc multi-tracked vocal wash are all subsumed into Bush’s striking originality: a uniquely female perspective sculpted from male sources. Breathing’s bold studio craft was a strong indication of things to come.

Elsewhere on ‘Never For Ever’, a vivified refinement of her earlier work is peppered with new sonic discoveries. Top 5 smash ‘Babooshka’’s story-telling (based on folk song ‘Sovay’) is wrapped in tight production that makes full use of the CMI’s sampling capabilities (and Abbey Road’s canteen crockery). As did ‘Army Dreamers’ with its rhythmic rifle click neatly underlining the bitter irony in the Irish waltz. A Roland drum machine provides the backdrop to ‘Delius (Song Of Summer)’, its featherweight beats rippling across the watery track while a cascading sitar creates a hypnotic fusion: East meets West, the future meets the ancient. Outside of this box of tricks, the most startling advance was ‘The Infant Kiss’. Inspired by Jack Clayton’s The Innocents, a film based on Henry James’ Turn of the Screw. The song was another delicate transgression (‘the child with the man in his eyes’) but as with ‘Breathing’ it quivers with a more forthright intensity: starker, weirder and speaking its own language.

The first number one album in Britain by a female artist, Never For Ever is a transitional work & the first number one British album by a female artist. Now oft-overlooked, it is the hidden gem in the Bush canon. With a trio of singles and novel touches throughout, Bush’s third was as fecund and ferocious as its Nick Price cover art – with its Bosch-like cornucopia of grotesque beauty – suggested. The "beautiful maggots"(Kris Needs) that were ever-present in Bush’s songs, previously contained by Powell’s production, were now unleashed, crawling across the listener’s brain.

If Never For Ever captured her at a crossroads, the next record would make no compromises. In December 1980, she went on Paul Gambaccini’s radio station and played a selection of her favourite music. Steely Dan and John Lennon got played, Zappa and Beefheart were left-field favourites but the music was largely culled from music beyond rock’s spectrum: whale song, Celtic harpist Alan Stivell, classical selections and the soundtrack from Peter Brooks’ Meetings With Remarkable Men. As she talks about the music of the last mentioned, The Contest Of The Ashoks, & how it "vibrates through the valley", it is hard not to think of the aural landscapes that were imminent. Along with the studio wizadry giving her work the requisite ‘oomph’, Bush was ready to expand her palette more fully away from traditional European/ pop musical modes. Brother Paddy, alumni of London College of Furniture, had already subtly coloured her work with arcane instrumentation. The traditional band set up failed to conjure the adequate images and emotions she was hankering for.

Assembled over the course of a year (back then an inordinately long time) with a revolving cast of engineers and recording locations, The Dreaming, her fourth album, was born of an exhaustive and exhausting gestation. It’s as if the studio itself became the same kind of amalgam of womb/ airless bunker so powerfully evoked in ‘Breathing’. Del Palmer, Bush’s then partner and musical sounding board, talked of "coming up" from the windowless Advision studio while Bush herself referred to just "watching the evening news before returning to the dingy little treasure trove to dig for jewels". At one point, all three of the legendary Abbey Road Studios were utilized for the sessions. Soon after promoting the album, Bush was diagnosed with nervous exhaustion and it was three years until the release of 1985’s triumph, Hounds Of Love.

The album was not without its obstacles. She talked of a terrible case of writer’s block. Initially she recruited Hugh Padgham, due to the Gabriel/Collins connection. While she praised the engineer, he seemed both unsympathetic to her madcap approach (and allegedly her then fondness for pot, according to Graeme Thomson’s excellent bio, Under the Ivy). Either way he was committed to working for The Police & recommended his assistant Nick Launay. The pair, bonded by their experimental curiosity and youth, proved to have a more productive simpatico. They mic’d up corrugated iron tunnels around drum kits in an attempt to mimic ‘canons’. The Dreaming melts the gap between pre- and post- punk, Launay having worked with both PiL and Phil Collins, shared Bush’s disregard for the old/wave divide. As early as 1980, Kris Needs noted her ability "to break down musical barriers and capture true emotion". On The Dreaming, proggy shifting time signatures and textures vie with a wild energy and the kind of poly-rhythms deployed on another Launay job, PIL’s Flowers Of Romance (1981). Another engineer, Paul Hardiman, had worked with both Rick Wakeman and on Wire’s seminal first three albums.

The Dreaming was the real game-changer. Back in 1982, it was regarded as a jarring rupture. "Very weird. She’s obviously trying to become less commercial," wrote Neil Tennant, the future Pet Shop Boy, still a scribe for Smash Hits. He echoed the sentiments of the record-buying public. Even though the album made it to number three, the singles, apart from ‘Sat In Your Lap’, which got to 11 a year before, tanked. The title track limped to number 48 while ‘There Goes A Tenner’ failed to chart at all. It was purportedly the closest her record label, EMI had come to returning an artist’s recording. Speaking in hindsight, Bush observed how this was her "she’s gone mad" album. But The Dreaming represents not just a major advance for Bush but art-rock in general. Its sonic assault contains a surfeit of musical ideas, all chiselled into a taut economy.

Bush had pirouetted into public consciousness to such an extent that in May 1981, she was asked to play the wicked witch in Wurzel Gummidge. Campy light entertainment was still knocking at the door, still smitten with her theatrical excesses. However, the following month, ‘Sat In Your Lap’ unveiled Bush’s new aesthetic. Inspired by attending a Stevie Wonder concert, it’s a violent assertion of creative control, a final nail in the coffin of the so-called elfin pop princess. Pounding pianos and tribal drums dominate, frazzled synth brass puffs steam as Bush’s vocals veer from clipped restraint to harnessed histrionics, at times rushing by with Doppler effect. The lyrics scratch their head in search of epistemological nirvana, a pursuit akin to the arduous process of making the album. "The fool on the hill, the king in his castle" goes searching for all human knowledge and the more he discovers, he realizes the less he knows.

The Dreaming’s disparate narratives frequently seem to be tropes for Bush’s quest for artistic autonomy and the anxieties that accompany it; the bungled heist in There Goes A Tenner, the ‘glimpse of God’ in ‘Suspended In Gaffa’, even the Vietnamese soldier pursuing his American prey for days in ‘Pull Out The Pin’. "Sometimes it’s hard to know if I’m doing it right, can I have it all?" she sings in ‘Suspended In Gaffa’, a Gilbert and Sullivan-esque romp in 6/8, as reimagined by Luis Bunuel. (She was also asked during the album’s recording to appear in a production of The Pirates Of Penzance). A peculiar mix of self-doubt and pole-vaulting ambition characterizes many of the songs here.

If ‘Sat In Your Lap’ vaguely chimed with Burundi beat of the times (Bow Wow Wow & Adam Ant ), its flip-side sounded like the inscription of a dream. Her reading of Donovan’s ‘Lord Of The Reedy River’ takes the minstrelsy of the original and filters it through disquieting modern psychedelia, the subtly shifting

palette not too dissimilar to the singles The Associates were chaotically assembling that year (see ‘White Car’/ ‘Q Quarters’). Where much of synth pop was revelling in pared down repetition, this music was incantatory, voluptuous, like Keats drifting ‘Lethe-wards’. Recorded in Townhouse Studios’ disused

swimming pool in order to evoke the sensation of floating down a river, the song’s grainy, low-resolution Fairlight motifs root it in its time but the aqueous phantasmagoria points the way forward to Hounds of Love’s ‘The Ninth Wave’. Like Lennon wanting to be the Dalai Lama on Tomorrow Never Knows, Bush was using technology as a means of metamorphosis.

She disappeared into the studio after the single’s release. Emerging 13 months later with ‘The Dreaming’ single, which sadly flopped. Repeated listens reveal a record that deserves to rank alongside her more famous songs. With its "flood of imagery painted into it", the track would have benefitted enormously from an extended mix but its dismal chart placing meant it wasn’t to become her first single release on 12". The semi-instrumental version on the b-side illuminates how Bush was becoming an inspired producer, creating tracks engorged in overdubs yet "full of space and loneliness".

Who else would cast Rolf Harris and John Lydon’s recent engineer on the same album? Harris’ didjeridu provides a hypnotic drone on the title track, a foreboding inversion of his own ‘Sun Arise’ (1962). Where Rolf’s early example of ‘world’ music conjures up a fictional outback full of sunburst optimism, The Dreaming is the sound of culture clash; rumbling ethno-textures are juxtaposed with the samples of slamming car doors on the Fairlight and the synthesizer’s soon to be ubiquitous preset, Orch. 5. Form and content coalesce impeccably; the ‘white’ man invades the Aborigines sacred turf, digging for plutonium and ore while archaic instrumentation (the Bullroarer) rubs shoulders with cutting edge technology. As with ‘Babooshka’, found sounds became a sonic lynchpin. Two pieces of marble being smashed together provided the song with one of its rhythmic layers.

The Dreaming elicits comparisons with Nic Roeg’s Walkabout(1971), not just due to its setting but in its tragic understanding of the human inability to communicate (a recurrent Bush theme). The film recites AE Housmann at its finale, so too a wind of ‘civilized’ change consumes The Dreaming’s finale. Into the aborigines’ hearts ‘an air that kills’, consigning their way of life to the ‘land of lost content. The animalistic chants and the Dreamtime itself, a belief system where Ancestral/ Totemic beings leave their fingerprints on the land or as other forms through reincarnation, evidenced her infatuation with transformation in sound and subject. The desire for artistic development, escaping the narrow confines of public perception and perhaps those early years watching Bowie parade his various personae (she was in the

Hammersmith Odeon audience July ’73 when he retired Ziggy) all seem to influence the symbolism of The Dreaming.

Released the same year, Peter Gabriel IV (aka Security) opened with a double punch that eerily echoes The Dreaming. ‘The Rhythm Of The Heat’ in its pictorial

three dimensions and ‘San Jacinto’ in its indigenous/’civilized’ worlds colliding. No more could people like Padgham dismiss her as a Gabriel wannabe. She was now a peer and innovator. The title track segues into ‘Night Of The Swallow’. Moon-glow piano balladry mutates into a torrid Irish folk blow-out; chiaroscuro Celtic cine-pop.

The Irish contributions, coming from members of Planxty and The Chieftans, were recorded over an all-night session at Dublin’s Windmill Lane Studios. Her musical imagination has the transporting power of cinema. As the scene moves from The Dreaming’s Antipodean soundscape to the outlaw glamour of a ceilidh band, it almost resembles the aural equivalent of the ‘magic geography’ of Bush favourites, Powell and Pressburger.

Another serpentine shape-shifter, ‘Night Of The Swallow’ deals with flight and imprisonment, a pilot begs his lover to "let me go" on a journey carrying potentially dangerous cargo (terrorists?). The lexicon of The Dreaming is rife with a similar tension: "wings beat and bleed" at windows, protaganists

lock up their bodies like houses and then "face the wind" or recall "rich, windy weather" when incarcerated. Escapoligists perish "bound and drowned". An interpretive stretch perhaps but woven into the lyrics is the thrill and the threat of change: a move away from the prison house of public perception that had plagued Bush in a lot of ways or confronting her own limitations. It could even be wrestling with the surrender to the discipline of rhythm. Its presence ebbs and flows, a rigid backbone that frequently crumbles, giving way to more free-flowing musical passages.

The proviso Bush had for The Dreaming was that everything was to "be cinematic and experimental". Movies inform The Dreaming as much as any musical influences. When describing ‘Pull Out The Pin’, she synaesthetically blurs the vocabulary of music with that of film, referring to wide shots and "trying to focus on the pictures" between the speakers. The song’s evocation of the Vietnam forest, "humid… and pulsating with life" is astonishing; all queasy protruding Danny Thompson double bass lines, musique concrete, Chinese drums and a distorted guitar sounding like a US soldier’s scratchy transistor. Much of these sounds were collated by drummer Preston Heyman in Bali. With its foliage of samples and cultures converging it nods to My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts, the landmark Byrne/Eno collaboration recorded in 79 but released in 81.

The duo’s work had a big impact on Bush (and modern music in general as the singer herself noted). Soundscapes like ‘Pull Of The Pin’ recall that album’s chattering spirit world but rendered more harrowing and de-funked. The Dreaming is haunted with voices in a vein akin to Byrne/Eno’s procession of exorcists and preachers (see Hounds Of Love’s ‘Waking The Witch’ too). Male voices make frequent cameos, sometimes with a stentorian authority and at other times with an almost subliminal creepiness. (Listen out for Paddy Bush’s barely audible, ‘It’s cold outside" on ‘Get Out Of My House’). Bush’s own agile voice changes character and pitches as if Bush was presiding over a séance.

Avant-music hall crime caper ‘There Goes A Tenner’ was composed on piano but decorated with the kind of muted faux-brass that flashes forward to Timbaland/These New Puritans and wistfully glances back at Pepper’s marching band. It opens with Bush’s mockney delivery only to reference the most iconic US silver screen gangsters as the song shifts from parody to pathos; chirpy Ealing comedy darkening into film noir. If the synth was the totem of a brave new world, Bush was using it to put across the great sadness of the era. ‘Tenner’’s queasy Synclavier sounding like the chrome machinery of Steve Winwood’s ‘While You See A Chance’ gone defective.

It hurtles towards a poignant finale, as compressed as those b-movies that inspired it. Squeezing the conversational into the musical, Bush courts ridicule with pastiche and then confounds the listener with the jailed bank-robber’s genuinely moving account of a freer life ("when you would carry me, pockets

floating in the breeze"). The song’s failure to chart, derided perhaps as a Madness jape by cursory listens, make it one of her most underrated musical dramas, swiftly executed and full of nuance.

Something of the disarming menace in Bernard Herrmann’s music for Hitchcock hangs over The Dreaming’s darkest corners, ‘Leave It Open’ and ‘Get Out Of My House’. Both are sublime slices of musical madness; bad acid trips through broken lives, controlled cacophony, post-punk pantomime. Oddball novelty Napoleon XIV’s ‘They‘re Coming To Take Me Away Ha-Ha’ was a childhood favourite and its disturbed comedy gets the serious treatment. ‘Get Out Of My House’ repositions A.L. Lloyd’s reading of the metamorphic folk tale of romantic resistance, ‘Two Magicians’ in the domestic asylum of Stephen King’s The Shining. It ends the album in a resounding bray of donkeys and drum talk, as absurd and harrowing as Lynch soundtrack.

These are thunderous drumscapes with spectral atmospherics blowing through them, as if the gated reverb’s quiet/loud dynamic amounted to a modus operandi unto itself. The madwoman in the attic gets a modern jolt, Gabriel’s ‘Intruder’ is now the occupant too. ‘Leave It Open’ is an exorcism of ‘In The Air Tonight’: edgy tension exploding into more thunderous gated drums. Both songs are about how "we open ourselves up and close down like receptive vessels", often at the wrong times. Bush was already beating a retreat from the invasion of fame.

In 1985, Peter Swales noted how Bush’s music often seems "like a virtual compendium of psychopathology …at turns melancholic, obsessional, hysterical… but as a sign of strength in service to the song, rather than weakness". How personal the pain is in these songs, is a moot point. Bush has always, from that recreation of Catherine Earnshaw’s ghost onwards, displayed an almost Keatsian negative capability, a thrilling surrender to the subject of any given song. But there is palpable anger in the metamorphosis here, a sublimated riposte to all the condescension she endured so placidly. When talking about her writer’s block period in 1981, she mentions a "horrible, introverted depression". A trace of the singer must lurk in these committed performances.

It remains a terribly sad record. A treatise on "how cruel people can be to one another, and the amount of loneliness people expose themselves to". Perhaps John Lennon’s murder and the dog-eat-dog ethos of Thatcherism had cast their shadow here. While the record was being made, the Falklands crisis escalated and unemployment rose. Many of The Dreaming’s characters seem to be caught in the vice grip of western ‘civilization’; the hapless robber in ‘There Goes A Tenner’, the aboriginal way of life on the brink of erosion on the title track, the Vietnamese soldier meeting his American nemesis on ‘Pull Out The Pin’. They may symbolize the tightrope walk Bush felt she was embarking on with the record. But this dense and allusive stuff with twists and turns requiring as many footnotes as TS Eliot’s The Waste Land, shares that poem’s occidental disenchantment.

And like that modernist masterpiece, The Dreaming glimpses at a very metropolitan melancholy. Bush would never make an album in London again, a city she felt had an air of dread hanging over it’. ‘All The Love’, a forlorn musical sigh, features percussive sticks imitating Venetian blinds turning shut. It climaxes with messages from Bush’s actual malfunctioning answerphone: all very modern alienating devices, straight from the same world of Bowie’s ‘Sound & Vision’. This was after all, the year Time magazine voted the computer as person of the year. Palmer’s ECM-like drowsy bass almost sobs with regret.

Throughout The Dreaming, sound speaks. ‘All The Love’ is subdued relief. But its constituent parts hover desolately in the mix, pitching a ‘lack of love’ song with a choirboy, somewhere between Joni Mitchell’s road trip jazz on ‘Hejira’ and the void of Nico’s ‘The End’. Full of space & loneliness.

At the centre of this creative storm is Bush. The vocal performances are a multi-faceted assault on the singer’s sometimes squeaky, whimsical past. There are guttural, larynx-shredding exclamations juxtaposed with whispers, sometimes on even the softer songs. A master of counterpoint and vocal embroidery, which Bush attributed to her mother’s Irish ancestry, the singer layers the songs with kaleidoscopic variety. Even the mellifluous ‘Suspended In Gaffa’ has shrieking incisions. Her voice is largely deeper and thicker than before, the unbridled emotionalism now more potent, due to its stringent control. On ‘Houdini’, a pint of milk and two chocolate bars were consumed to give her voice the required "spit and gravel" (‘Night Of The Swallow’ and ‘Pull Of The Pin’ also have phlegmatic operatics).

She plays the role of the escapist’s wife, trying to contact him through a barrage of fraudulent mediums. Her immersion in the part is unnerving, imbuing the song’s old world romance with real gravitas. It is a song, like so many of hers, triggered by an emotive spark rather than prosaic veracity. Love’s ability to transcend the ‘clutches of eternity’ had been an alluring theme for the singer since ‘Wuthering Heights’ (another barrier to be broken down). The chamber-pop of ‘Houdini’, replete with Eberhard Weber’s fluid bass runs, plays like a maturation of the earlier song, shorn of youthful theatrics and soft-rock soft focus.

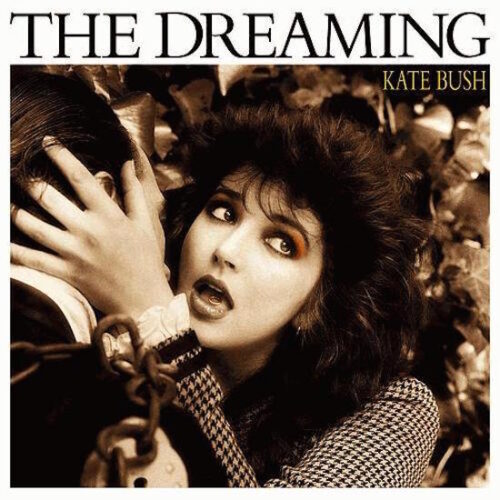

The arrangement is one of her finest, weaving a spidery web of pearlescent piano, underwater electronics and a string section as moving as ‘Eleanor Rigby’ in its severe lack of sentimentality. Pencilled in as a possible single but sadly never released, ‘Houdini’ is the album’s cornerstone, memorably captured on the cover’s sepia-toned art.

She filters her vocals through the same effects as the music; delay, compression, flange. Sometimes they’re daubed so heavily in processing that she sounds as sharp and precise as a laser beam. Far from being over-produced, each treatment is used with acute sensitivity only adding ballast to the music‘s visceral punch. Each vocal part is placed within the stereo image, like every other overdub, with meticulous care. Occasionally her unvarnished voice lets rip but generally there’s a Lennon-esque distrust of the dry, natural voice. The Dreaming bristles with the same kind of inventive mania that dominated The Beatles’ work circa Sgt. Pepper/Magical Mystery Tour.

Only this was not the 60s, it was 1982, the year New Pop’s shiny subversion from within was about to be usurped by a blander corruption of its original manifesto. The yuppies were gaining traction and The Dreaming’s emotional wisdom belonged to another era while its pioneering spirit was too far ahead

of the pack to be digested. Dig deeper into 82, however, and an alternate universe emerges of studio bound xeno-pop, much of it with a darkly psychedelic tilt; The Associates’ Sulk, Peter Gabriel’s 4th, The Cure’s Pornography & Siouxsie’s A Kiss In The Dreamhouse. All form with The Dreaming a kind of ‘secret heritage’ that suggest the pre-Smiths musical landscape was far from barren. Psychedelia reared its head once more in this period, albeit in a more dank, miasmic incarnation: another new route for post-punk and a refuge from Thatcher reality.

Interestingly, Sioux’s ice queen was melting into sensuous curves while Bush was sharpening her edges. Bush’s artistry surmounts gender boundaries, both in her adoption of male roles and her exalted position, now at least, unencumbered by the usual baggage that plague most female artists. However, The Dreaming also occupies the lineage of bloody-minded brilliance inhabited by Buffy Sainte Marie’s Illuminations, Nico’s The Marble Index, Joni Mitchell’s Hissing Of Summer Lawns and Laura Nyro’s New York Tendaberry, Patti Smith’s Radio Ethopia and more. All of them are fearless genre-busters that resist being shoehorned into the marketplace or rock orthodoxy. The Mitchell album, doggedly uncommercial, cine literate with inter-continental musical flights is especially analogous, without sounding anything like Bush’s record.

An embarrassment of riches then, bestowed upon an unworthy rabble. The Dreaming was released to a baffled public but the more open-minded sectors of the music press acknowledged Bush’s achievement. Despite many laudatory notices, watching Bush and Gabriel’s respective appearances on Old Grey Whistle Test confirms what she was up against. Gabriel is afforded due reverence as an art-rock renaissance man, Bush, on the other hand, while covering roughly the same ground, is ever so slightly mocked. Behind her unwavering propriety, irritation smoulders. As with her appearance on Pebble Mill, the usually sympathetic Paul Gambaccini constantly frames the music in context of its radio playability or lack thereof. Bush looks bewildered and more than a little wan. The music she had created was no longer so easily assimilated by daytime TV.

Another tour was talked about but never transpired. She left London. At her parents East Wickham home she created a 48 track studio and returned three years later with the masterpiece Hounds Of Love, knocking Madonna’s Like A Virgin off the top spot. It elevated her into the pantheon of greats, a grand dame of Brit-pop at the tender age of 27. The first side with its consistent rhythms, arresting hooks and l’amour fou turned her into a hi-tech post hippy hit machine. The singles’ videos were glossy excursions, some of them conceived on film rather than video. By the ‘Hounds Of Love’ promo she was directing herself. Another area the "shyest megalomaniac" wrestled control of. ‘The Ninth Wave’ was another tribute to her imaginative powers, the song suite being the sexy, acceptable face of prog rock. She even had a hit in America. Although she had to change the name from ‘A Deal With God’ to ‘Running Up That Hill’.

But it was The Dreaming that lay the groundwork. It ignited US critical interest in her (including the hard-assed Robert Christgau and the burgeoning college radio scene finally gave Bush an outlet there. Hounds Of Love, remains the acme of this singular talent’s achievements. It uses ethnic instrumentation while sounding nothing like the world music that would be popularized through the 80s. It is a record largely constructed with cutting edge technology that eschews the showroom dummy bleeps associated with synth-pop. At the time, she talked of using technology to apply "the future to nostalgia", an interesting reverse of Bowie’s nostalgic Berlin soundtrack for a future that never came. Like Low, The Dreaming is Bush’s own "new music night and day" a brave volte face from a mainstream artist. It remains a startlingly modern record too, the organic hybridization, the use of digital and analogue techniques, its use of modern wizadry to access atavistic states (oddly, Rob Young’s fine portrait of the singer in Electric Eden only mentions this album in passing).

For such an extreme album, its influence has been far-reaching. ABC, then in their Lexicon Of Love prime, named it as one of their favourites, as did Bjork whose similar use of electronics to convey the pantheistic seems directly descended from The Dreaming. Even The Cure’s Disintegration duplicates the track arrangement on the sleeve and the request that ‘this album was mixed to be played loud’. ‘Leave It Open’‘s vari-speed vocals even prefigure the art-damaged munchkins of The Knife vocal arsenal. Field Music/The Week That Was arrayed themselves with sonics that seem heavily indebted to Bush’s work here. Graphic novelist Neil Gaiman even had a character sing lyrics from the title track in his The Sandman series. John Balance of post-industrialists Coil confessed that the album’s songs were all ideas that he later tried to write. But Bush got there first. And The Dreaming remains a testament to the exhilarating joy of "letting the weirdness in".