“He said in the cosmos is a single sonic sound

That is vibrating constantly

And if we could grip and hold on to the note

We would see our minds were free”

Judas Priest ‘Dreamer/Deceiver’

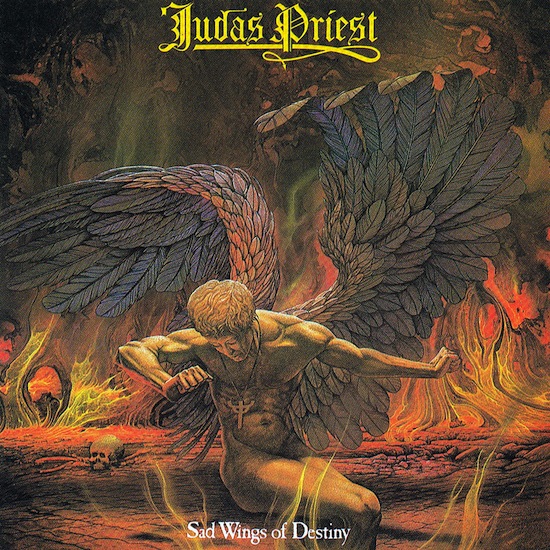

Heads bang, speakers shake and the earth, lost in a wasteland of nothingness, grinds slowly on its axis. The pursuit of life as a metalhead most often feels very much like being part of a vast primeval continuum. For almost its entire history, heavy metal has been forced to endure derision, incomprehension and mirth from all quarters, viewed as the stuff of shrieking and vulgar overstatement, or as some kind of retrogressive and primitive throwback, Kubrick-style, to the days of prehistoric man. All of which, naturally, is completely true. Yet ignores the fact that the cosmic collision of raw power, histrionic drama and electrifying energy can also amount to nothing less than a life-affirming force. And there can be few bands more crucial to metal’s lifeblood than Birmingham’s Judas Priest, whose vibrations, a full forty years after the release of their cataclysmic second album Sad Wings Of Destiny, still resonate far into the reaches of space.

It’s now almost become the stuff of cliche to relate that the industrial origins of Birmingham were what gave birth to Heavy Metal – the incessant violence of the machinery, and the Faustian infernos of the iron foundries – which also found a transatlantic parallel in the Detroit motor industry that helped formed the psychic backdrop to The Stooges and The MC5 – creating a mighty clangour that found its way into a generation of escapist imaginations.

Although the majority of self-appointed rock historians tend to pinpoint the birth of Heavy Metal either at the 1968 release of Blue Cheer’s gloriously primeval ‘Vincebus Eruptum’ or the use of those two words in the same year in Steppenwolf’s ‘Born To Be Wild’, 1970 was the year that four berserkers from just this industrial landscape – named Ozzy, Tony, Geezer and Bill – accidentally creating an entire subculture in a twelve hours studio session fuelled by blues, soul, narcotics, booze, horror movies and the occult. Yet the early seventies, by any standards, were a fruitful time for heavy rock, and an era in which its evolutionary process was hammering forward at startling velocity, as legions of baby-boomer bands around the world built on the speaker-rupturing innovations of Hendrix, Cream, The Who and Led Zep with the experimental, psychedelic sensibilities of the late-sixties and the psychic spectres of Vietnam and Altamont ringing in their ears.

Deep Purple had already – some might say cynically – seen the writing on the wall after the arrival of Led Zeppelin and replaced their genteel and stylish vocalist Rod Evans – a fella who wouldn’t have been out of place in Manfred Mann – with someone capable of screaming loud enough to bother forces of health and safety, and following a catastrophic false start with 1969’s Concerto For Group And Orchestra, the barnstorming In Rock sent shockwaves through the realms of the lank-haired and the shiftless around the globe, with Ian Gillan’s ferocious shriek to the fore. Elsewhere on a global scale, way-out outfits with names like Sir Lord Baltimore, T2, May Blitz, Atomic Rooster, Uriah Heep, The Edgar Broughton Band, Groundhogs, Elias Hulk and Haystacks Balboa were dishing out uncompromising rackets that feverishly vaulted forth into the unknown with their amps on eleven and their cheesecloth shirts untucked.

Click here for the Metal 1970AD Playlist on Spotify

Yet 1971 was still more incredible, and in many ways a pinnacle for loud. experimental and transgressive music still to be matched in modern history – this was a year in which not only acknowledged behemoths like Led Zep 4, Who’s Next and Master Of Reality hit the racks, but beyond hard rock. the head-spinning litany of Can’s Tago Mago, Funkadelic’s Maggot Brain Van Der Graaf Generator’s Pawn Hearts, Faust’s debut, Flower Travellin’ Band’s Satori, Groundhogs’ Split, Comus’ First Utterance, Budgie’s debut and Pink Floyd’s Meddle blazed a trail into the consciousness, and the average self-respecting head might have been forgiven for thinking that the horizons of the countercultural world would only extend further forthwith.

Click here for the Metal 1971AD Playlist on Spotify

Unfortunately, though, such was not to be the case. The post-psychedelic expansion that took place at the dawn of the seventies, bringing with it legions of experimentalists and transgressors who put volume and velocity forward as priorities in order to create sounds that were as ambitiously outré as they were ear-piercingly loud, was soon to be replaced in hindsight by a small selection of artists slowly becoming titans of the heavy art form, with all the hubris and vainglory that this implies. Moreover, the rot had set it fairly early. Made In Japan by Deep Purple has become known as a mighty testimony to bludgeoning rock power, a cavalcade of an unholy marriage between instrumental virtuosity and sheer brute force. Yet to a younger punter in the here and now, the fivesome’s trademark and rather self-regarding ability to mercilessly over-extend every song to an orgiastic frenzy twice its original length can’t help but raise eyebrows. By 1973, Led Zeppelin were similarly playing the shows that were later to surface on the tortuous Song Remains The Same, with a half-hour long ‘Dazed And Confused’, later to feature the visual accompaniment of Jimmy Page meeting himself reincarnated as a wizard atop a mountain, as its centrepiece.

Click here for the Metal 1972 Playlist on Spotify

Four decades, on, a regular procession of documentaries have retrospectively over-simplified our perception of the mid-‘70s into another litany of cliches, endlessly repeating aerial footage of Emerson, Lake & Palmer’s three trucks on a motorway before cutting to the gurning visage of John Lydon. Whilst on the one hand it may be tricky for anyone who wasn’t around in that era – such as this writer – to understand the impact of punk across the cultural landscape, it’s also all too easy to assume that 1976 was a year in which anyone across the UK not clad in bondage gear was shunned as passé, when punk rock was actually the preserve of a metropolitan vanguard of no more than a few hundred people. Such is even the lunacy of the very Wikipedia page of Sad Wings Of Destiny, which blithely states that this album “weak sales as it was released just as punk rock was dominating the spotlight in the UK” – this despite the fact that in March 1976 when it was released the first Ramones album was yet to be released and the Sex Pistols were still playing the Nashville supporting the 101ers.

Click here for the Metal 1976 Playlist on Spotify

However, a similar malaise had apparently taken hold of hard rock and heavy metal by this era to the broader disenchantment which led to punk rock in the first place – whilst there were large, grandstanding and enduring rock classics made that year – such as Thin Lizzy’s Jailbreak, Rush’s 2112, Rainbow’s Rising, and Kiss’ Destroyer the sound appeared in need of an injection of adrenaline and inspiration. Enter The Priest.

The fact of the matter may well be that Judas Priest were simply too far ahead their time to have immediate commercial success with Sad Wings Of Destiny. Strange as it may sound, it was primarily only this band and Scorpions – the latter of whom are now often erroneously viewed as a somewhat middle-of-the-road phenomenon in the light of ‘Wind Of Change’ and a certain amount of other aesthetic clangers, yet whose similarly high-energy and neoclassically embellished assault on the same year’s Virgin Killer was only partially hampered by one of the worst sleeves in metal history – who were transgressing the boundaries of heavy metal in a significant fashion.

Both bands fundamentally updated the heavy metal paradigm by bringing a new intensity and focus that entirely schemed many of the blues-based cliches and lumbering baggage of yore. Moreover, Sad Wings Of Destiny, from the sleeve and somewhat portentously poetic title down, was fundamentally a record dealing more than good-time rock & roll or the stuff of the Friday night boogie band, rather a realm of violence, conflict and drama fit to render heavy amplification as the stuff of a gravtias that only Sabbath had previously essayed with any real conviction.

Indeed, the momentum of Priest’s evolution gave life to a startling metamorphosis in both sound and appearance in the mid to late 70s, something akin to a superhero transformation in which the psychic power of their more-of-everything attack began to manifest itself visually. The ‘before’ of this equation is displayed in full colour by the legendary Old Grey Whistle Test footage from 1975, in which, despite Priest attacking the alternately dramatic and bludgeoning ‘Dreamer/Deceiver’ with enough operatic power and finesse to even render Whispering Bob Harris comparatively animated, their flowing post-hippy garb is a wicked world away from the image that later became their trademark, with the long-locked open-shirted Rob Halford even bringing to mind Pentangle’s Jacqui McShee.

Yet for all their fashion crimes, his was a band sonically ahead of the curve to a degree that nowadays beggars belief. The influences may be clear – the bludgeon and groove of Sabbath, the muscle and wail of Purple, the operatic drama of Queen, plus a dash of Hendrix in K.K. Downing’s frenzied lead howls – yet the ambition is far-reaching, the delivery marked by an intensity and finesse unlike anything in sight on the 1976 landscape – the riffing scalpel-sharp, Rob Halford’s theatrical approach and technical mastery a thing to behold.

However, despite the fact that early thrash pioneers like Scott Ian and Venom regularly cite Priest as an influence in terms of being more balls-out and intense more of the time than any other band, a certain amount of the magic of 70s Priest arrives courtesy of the band being completely unafraid to balance out feverish thundering riff science with moments that border on Neil Diamond territory. This is a band with the balls to delivery a murky yet ornate ballad like ‘Epitaph’, complete with piano and stacked vocal harmonies. yet then lurch into a rollicking Sabbathian fantasy barnstormer like ‘Island Of Domination’. A band unafraid to deal out the grand guignol of ‘The Ripper’ (a song arguably more Spinal Tap than even Tap themselves) with such slavering relish, incisive instrumental complexity and atmospheric panache that disbelief is suspended until further notice. Yet it was also an album made while band members were struggling by on one meal a day and working as gardeners and delivery drivers, perhaps spurred on to create still more vivid fantasy landscapes and sinister psychic spectres by the mundanity of their surroundings.

Central to the magic of Priest was their ability to take tired shapes and reinvent them anew – ‘Victim Of Changes’ originated as two songs with the somewhat Creme Brulée-esque titles of ‘Whiskey Woman’ and ‘Red Light Lady’, yet combined and supercharged by Priest’s full-throttle attack, Halford’s otherworldly howls, one of Downing’s most horrifyingly tuneless yet pole-axingly awesome solos (predating the legendary noise-not-music lead style of Slayer’s Jeff Hanneman and Kerry King by a decade) and a masterful grasp of dynamics that treated sober restraint, anthemic bravura and righteous heaviness with equal import, pub band cliche was alchemically transformed into an epic metal blueprint for the ages.

Moreover, by upping the ante so savagely Sad Wings Of Destiny helped to kick-start a second wave eventually to find true fruition in the almost indecently exciting punk-style grass roots movement of the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal. By 1980, not only was the genre revitalised (much to the chagrin of the diehards who were forced to discuss a resurgence of something that by their reckoning had never gone away) but it was producing a litany of thrilling records that would then inspire new behemoths like Slayer and Metallica to tread the earth.

It’s now nearly fifty years since Vincebus Eruptum and thirty since both Reign In Blood and Master Of Puppets. Indeed, most metalheads will be familiar with being reminded of a different anniversary seemingly every couple of days in the here and now, perhaps leading to the conclusion that heavy metal may be on the verge of following other realms of guitar music to be perceived as either a classicist art form, a largely nostalgic one or (and this phrase itself can’t help but provoke a shudder) a heritage genre. Yet the fact that new generations of fans still embrace music that spent most of the 1990s derived as a laughing stock tells another story, more that classic heavy metal has an appeal, rooted in its primal charge and fearsome intensity that transcends fashion and artifice will not fall prey to rust and ruin over the passing of years. Moreover, there are few monoliths more fit for the ages than the gargantuan gothic construction that is Sad Wings Of Destiny.

With thanks and apologies to Andrew Steen and David Terry