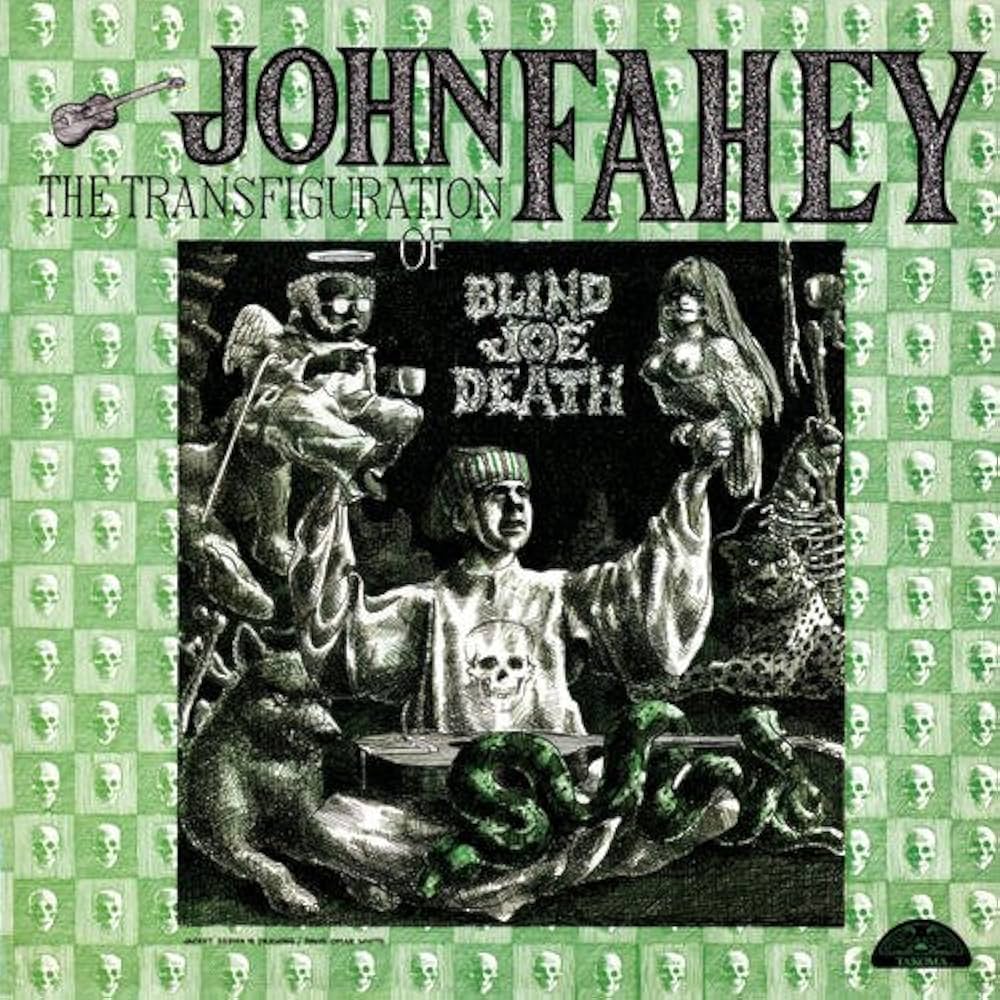

On The Transfiguration Of Blind Joe Death, the ‘American Primitive’ guitarist John Fahey’s ability to create something so memorable from so few ingredients remains striking even 60 years on. Nearly every track is a few minutes of solo acoustic guitar, save for two accompanied by the banjo player L. Mayne Smith, but each seems to be suffused with an unusual, haunting atmosphere that is wholly its own. In fact, the simplicity is integral to creating that atmosphere: the homemade, bare-bones intimacy of these recordings, varying in fidelity and replete with tape hiss, means you’re almost able to smell the wooden kitchen table, the gas stove, the dog curled in the corner, that might have surrounded Fahey as he played. Not least because one song, ‘Poor Boy,’ is actually brought to a halt by a barking dog. Fahey pauses and gently shushes it, before picking up where he left off, unfazed. It’s an odd, comical moment of not-quite-breaking-the-fourth-wall; an acknowledgment of the world outside of this music that feels surprisingly post modern, and not as wholly reverent towards the past as one might expect from a folk record from the mid 1960s.

There is a cheerful solitude to the sound of John Fahey. Without even a voice to accompany it, his fingerpicked steel string guitar can seem naked and unadorned; an inward sound of someone playing to and for themselves. But countering that is Fahey’s gift of being able to sound like more than one person, to accompany himself: the relentless forward motion of his thumb’s basslines, thrumming under each song, keeping things moving with a freight-train regularity, and above that, melodies so bright and clear and implausibly coming from one pair of hands, that there seems to be no need for a voice at all. His music has the intriguing quality of having something missing and being wholly complete and self-contained at the same time.

Another quality that has helped this music to stay fresh, 60 years on, is the fruitful tension between the traditional and the modern; the use of conventional folk and country melodies and chord progressions, alongside subtly strange melodic left turns that divert into less familiar terrain. Aside from the title of ‘On The Sunny Side Of The Ocean’, which cleverly alters a well-worn phrase to make it unfamiliar, the song is remarkable for how it moves through an array of different melodies, some straightforwardly pretty, others darker and more discomfiting, with a fluidity that means you never quite get a grip on the ‘verse’ or ‘chorus’, or the prevailing mood of the track. ‘Come Back Baby’, meanwhile, the second of two tracks where Fahey is accompanied by L. Mayne Smith, more or less adheres to the familiar 12-bar blues, except for one chord within the structure, which somehow lifts it into a more modern register. And ‘Tell Her To Come Back Home’, played on shimmering 12-string, shifts about halfway from a wistful major key into bluesy minor, and then back again. It is these subtle turns which slightly wrong-foot the listener, and create an emotional ambiguity which makes the album more than just a selection of traditional melodies faithfully strummed.

This modern sensibility is perhaps why Fahey has been able to have a strong influence in contemporary music, particularly in folk music that has an alternative, exploratory edge. In America, Adrianne Lenker’s use of unusual tunings, and her extended guitar pieces in Instrumentals (2020), are certainly reminiscent of Fahey, while William Tyler’s oeuvre of instrumental guitar work might not exist if that niche hadn’t already been carved out back in the 1960s. Meanwhile, the current folk resurgence in London venues such as the MOTH Club, often drawing out the stranger, more haunting qualities of the genre, certainly owes something to Fahey’s oddness. After the post punk revival that flourished after Brexit in the UK, a new moment for folk music might imply a fatigue with abrasiveness and overt politics, and a desire instead for music that is gentler, perhaps more traditionally ‘beautiful.’ But confrontation and discomfort are qualities which seem to have carried over into this new wave, even if the instrumentation is more likely to include a hurdy-gurdy than a distorted guitar. Over in Ireland, one of the most popular tracks by Lankum, ‘Go Dig My Grave’, consists of six sharply dissonant minutes of dread, underscored with a drone that draws from the same well that Fahey did when he blended American folk with the tones of Indian raga in his ‘Days Have Gone By’ compilation. Meanwhile, the programming of Broadside Hacks, a collective and label based in London, has been releasing the trip hop-infused folk of Milkweed and the witchy, gothic chants of The New Eves. Though these artists may not cite Fahey as a direct influence – they might not have heard him at all – but their subversion of the pastoral, homely realm of folk into something newer and darker certainly has a precedent in Fahey’s free melding of folk, Delta blues, world and classical music, over half a century ago.

The ability of Fahey’s distinctive style to feed into the traditional music of other countries is also striking. Broadside Hacks has put out the instrumental work of Gwenifer Raymond, the Welsh-born, Brighton-based musician, whose pieces often take inspiration from Celtic mythology. She explicitly styles herself as a ‘Primitive Guitarist’ and has written about the formative influence of Fahey, and how he offered a way beyond the grunge and punk music she played as a teenager. Indeed, Fahey demonstrates the possibility of embracing the counter culture without needing to turn on an amp. Meanwhile, The Gentle Good, alias of Gareth Bonello, a folk artist who often sings in the Welsh language, recorded an instrumental EP of Welsh Plygain carols back in 2014, titled Plygeiniwch!, inspired by Fahey’s weirdly enchanting Christmas albums. He also wrote an instrumental tribute to Fahey, ‘Takoma Park Rambler’, with Richard James of Gorky’s Zygotic Mynci, in the same year. There seems to be an affinity between Fahey and Welsh folk artists; maybe it’s something to do with all the mountains in Maryland and south Wales.

A sense of openness to Fahey’s compositions – Amanda Petrusich describes them in The New Yorker as like “looking out over flat water” – seems to make them ripe to be reappropriated in new contexts. They never sound wholly rooted in one place; this is partly due to the absence of voice and lyrics, which always give so much away about the performer, but also because of Fahey’s patchwork approach to genre, weaving folk and contemporary classical and whatever else he was interested in. His ‘American Primitivism’, then, a seemingly problematic term in itself, is actually neither very American nor very primitive. The inaccuracy of the label was probably a deliberate, ironic joke, aimed at differentiating himself from more earnest, ‘authentic’ practitioners, while playing up his lack of formal training – but that playfulness, also evident in the extensive and wild fictional liner notes in his albums, meant that Fahey would never belong to a rarefied world of tradition. Instead, he offered a modern, melancholic yet buoyant sound, heavily indebted to the Black Delta blues guitarists like Charley Patton, whom he studied, but refracted through other worlds of music. That un-rootedness perhaps allowed him to more easily speak to artists beyond America – beginning with contemporaries like John Martyn and Bert Jansch, and continuing with the new wave of artists today.

The Transfiguration Of Blind Joe Death might be the best representation of Fahey’s modest yet far-ranging musicality at its peak. It’s a carefully crafted hodgepodge from which anyone can take something, and remains a fresh and inspiring demonstration of what can be done with just an acoustic guitar and a microphone, 60 years later.