The further you move away from the horizon, the harder it is to see your starting point. And so, too, with the passing of the years, fact soon blurs into selective events and the memory banks begin to resemble a warehouse that’s been neglected for far too long; boxes are left open, their contents lying randomly on the floor and any pretense of careful filing has long since been discarded. There’s a vague idea of where things are and where they might be, but by this point we’ve settled down with the unreliable witness that is conventional wisdom.

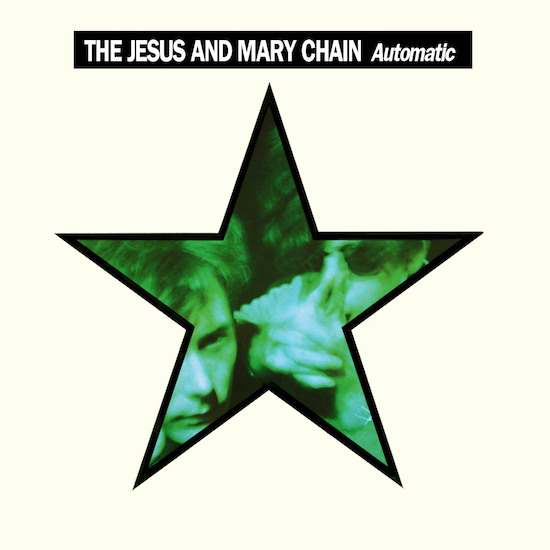

Automatic is an album that’s frequently given short shrift by any number of biographers, commentators and scholars who erroneously view the record solely as a streamlined and digital assault on the American market that lacks the bite of its predecessors. Crucially, the mistake is made all too often of presenting The Jesus And Mary Chain as a hermetically sealed unit with one eye looking permanently in the rear view mirror at the debris and detritus strewn across the rock & roll highway. Yet this is to ignore the band’s role in the here and now of the closing chapters of the 1980s with their finely tuned pop antennae picking up what was going on around them. And what was going on around them was a heady and potent cocktail of squelches, beats and noise.

Released in the autumn of 1989, Automatic’s roots go back some 18 months and the unleashing of The Jesus And Mary Chain’s eighth single, ‘Sidewalking’. Though rooted in the classicism and mythology of rock & roll, the band were never ones to stand still. If their second album, Darklands, had wrong-footed those expecting a repeat of Psychocandy’s bittersweet sonic fruits with its more considered approach, then ‘Sidewalking’ consolidated both of those records along with The Jesus And Mary Chain’s ability to startle and surprise from a variety of angles. And it’s with the single’s 12” incarnation that the band’s lofty ambitions and achievements can be properly appreciated. Built on a foundation of a ramped-up sample of Roxanne Shanté’s 1984 debut single, ‘Roxanne’s Revenge’, and ushered in by teasing amounts of feedback, string scrapes and reverb crashes to create an unsettling aural dystopia, the eventual arrival of the two-note bassline and heavily intoxicated Duane Eddy nods come less as relief and more as carnal release. So while the vehicle is still recognisably rock & roll, the engine is being powered by something else entirely.

By the time of ‘Sidewalking’s release, two new sounds were beginning to make their presence felt on an increasingly stagnating pop landscape. Thanks in part to landmark albums by Public Enemy (Yo! Bum Rush The Show) and Eric B. & Rakim (Paid In Full) among others, hip hop was no longer seen as a novelty. Indeed, the former were anything but a novelty as black consciousness concerns steered hip hop away from what was largely seen as party music and into a medium for uncompromising and controversial political and social discourse. Moreover, the genre was starting to rival rock music as the dominant youth culture by the end of the 80s. In doing so it managed to upset all manner of bogeymen in need of upsetting. Any number of rock bores were up arms as to whether hip hop constituted so-called “real music”, an argument that’s still being tediously made to this day. Elsewhere, the US establishment had already moved to throw its arms up in horror with the formation of the PRMC, but here the motives were more dubious and sinister. But what was undeniable was that here was a movement that not only matched but also exceeded punk rock in terms of reach and influence. And like punk, it was viewed as a major threat to society.

Also causing ever expanding waves was the sound of acid house. As with punk before it, it too emerged from the American underground before being picked up by British youth and refined with its own argot, fashion and drug of choice. It also challenged the musical status quo with an assault ranging from chart hits that hadn’t been endorsed by radio play or media coverage through to raves that made a profound impact on club culture the length and breadth of the country. And like punk and hip hop and pretty much every youth movement before, it soon had the mass media in a moral panic. But this time, the backlash differed in its upset; while the likes of teddy boys, mods, punks, skinheads and others had been demonised over the violence that had been prevalent in their cultures, here the self-appointed guardians of morality were frothing at the mouth over the drug taking at its centre. And the irony of course was that violence was the least likely outcome of getting loved up on the dancefloor; the clue, after all, was in the name: ecstasy.

The Jesus And Mary Chain were far from unaware of what was going on beyond their own universe. They were, after all, pop kids from the get-go, always alert to changes on the musical landscape. The proof was in ‘Sidewalking’ and what was to follow.

“We dipped our toes into the hip hop waters at the time,” Jim Reid told this writer in 2008. “We were listening to Stetsasonic and Run DMC and stuff like that."

But they were also taking note of the other sounds making an impact on the cultural landscape. Surprisingly, it was bassist Douglas Hart who made the initial overtures beyond the band’s output. Finding himself gradually drifting away from Jim and William Reid as the pair took greater control of the music they were creating, Hart had begun exploring the possibilities of film making and had begun to make promotional videos for other artists. Like William Reid, Hart dabbled with his own acid house experiments in the studio, but unlike the older brother had actually released his effort. Working with Peter ‘Pinko’ Fowler – a contemporary of John Loder, the owner of Southern Studios where Psychocandy had been recorded – under the name Acid Angels, the pair made a convincing stab with the Donna Summer-sampling single, ‘Speed Speed Ecstasy’. And while its motorbike intro was pure Mary Chain, what followed was straight from the dancefloors that had caught Hart’s attention in the first place.

He wasn’t the only rocker paying attention to these developments. Working with The Fall’s Marcia Schofield, bassist Barry Adamson and Cocteau Twins’ Robin Guthrie, The Gun Club and Bad Seeds guitarist Kid Congo Powers released the In The Heat Of The Night EP. While the title track and B-side, ‘La Historia De Un Amour’, betrayed their hip hop influences, the closing number, ‘Cat Tabu (Cat House)’, was pure and squelchy acid.

Elsewhere, The Shamen began their transformation from 60s-inspired psych-rockers to fully paid-up ravers on the stepping stone album, In Gorbachev We Trust. An erratic listen, it veers from the industrial polemic of ‘Jesus Loves Amerika’ through to the hip hop informed title track. They’re at their most convincing when going for acid house, most notably on ‘Synergy’ ("MDMAmazing!" sings Colin Angus with all the passion of a convert turned zealot) and ‘Transcendental’, a groover that couches the ecstasy experience in sacramental terms. From the vantage point of 30 years, both tracks hold up far better than the chart-worrying hits with which they broke through to the mainstream. The latter was given a particularly muscular remix by Chicago producer Bam Bam, who’d already made an impact with the acid banger ‘Give It To Me’ and the genuinely creepy ‘Where Is Your Child?’

Leaving aside efforts by the likes of Pop Will Itself who exhorted us to, “Sample It, Loop It, Fuck It And Eat It”, Age Of Chance who ploughed their own individual furrows from rock to dance (who have been reappraised elsewhere on this site), it’s to The Jesus And Mary Chain where we must focus our attentions. As evidenced by ‘Sidewalking’, the Reid brothers’ fascination with hip hop and the opportunities it presented with regard to their music had taken root and was set to grow into what was to become their third album, Automatic.

Their label had applied pressure in terms of securing the services of a big name producer with the ultimate objective of making further in-roads into the US market. Among the candidates touted for the job was Daniel Lanois, the Canadian musician and producer who’d done much to raise his profile thanks to his production work with Brian Eno on U2’s post-Steve Lillywhite output. Listening back to the instrumental breaks and codas on tracks such as ‘Bullet The Blue Sky’ and ‘One Tree Hill’ from The Joshua Tree, it’s not that much of a stretch to see why Lanois had been considered for the job. The layering on the former track displays an ability to take the guitar out of its comfort zone to stretch out into soundscapes and vistas. The latter’s break towards the end certainly proves his ability to work with distortion.

But it wasn’t to be. According to Jim Reid, Lanois’ enthusiasm for working with The Jesus And Mary Chain was brought to end when the brothers informed him that their primary contemporary influence was hip hop and that they saw their recorded future in the realm of sequencers and drum machines. And it’s certainly up for question as to how Lanois’ skills in creating wide spaces and ethereal atmospheres would have served the Mary Chain’s cause.

But if that working relationship failed to leave the starting block, the recording of Automatic saw the Reids cementing one with engineer, mixer and producer-to-be, Alan Moulder. It proved to be an astute choice. Having worked with electronic acts including Depeche Mode, Erasure and Jean Michel Jarre, he was in position to help JAMC achieve the objective they’d revealed to Daniel Lanois while managing to add a little bit more. For what’s immediately palpable from the opening rumble of ‘Here Comes Alice’ is a sleeker, more mechanoid groove than anything that the brothers Reid had achieved before.

Not that this was new territory for Jim and William Reid. Despite the briefest of tenures by Dead Can Dance drummer James Pinker when Bobby Gillespie’s replacement John Moore moved from behind the traps to his natural constituency of guitar, the Reids took total control of the music for Darklands and set about using a drum machine. By the time they took the album on the road for promotional duties, their live configuration was the same as The Sisters Of Mercy’s, albeit with spikier hair and considerably less paisley under their leather jackets.

But what was apparent was the degree to which the drums and sequencers were pushed to the fore. The programmed bass gave the album a more relentless sheen, as if it was daring its audience to keep up with its never-ending energy. It’s hard not to be reminded of James Cameron’s sci-fi classic The Terminator when resistance fighter Kyle Reece tells a terrified Sarah Connor of the cyborg chasing her: “It absolutely will not stop – ever – until you are dead!”

An overly dramatic assessment? Perhaps, but it’s one to fall back on once again when considering Automatic’s more driving rock & roll numbers: ‘Coast To Coast’, ‘Between Planets’ and ‘Head On’, tracks that are all cut from essentially the same cloth but delivered in different keys. All possessed of a knuckle-whitening, teeth-grinding quality, those unrelenting, centre-stage drums become utterly merciless when underpinning William Reid’s dampened string chugging. And once he starts to apply layers of six-string menace in the shape of sustained, slashed chords, Chuck Berry rhythms and minimal yet melodic lead breaks, it all begins to tie together to create music designed to get your ass on the floor.

Part of the genius of JAMC is that they always recognised rock & roll for what it really is: dance music. For sure, it got its name from the simple act and primordial joys of fucking, but when that energy is transplanted to beyond the hips to the feet, then the combination is simply unbeatable. Indeed, the secret to understanding them isn’t so much the violent noise they’re celebrated for, it’s more the music that’s based on the chassis of rock & roll, and with each subsequent release they’ve altered just what it is that sits on the framework. Automatic, then, is the album that fuses dance from a variety of different angles.

This collision of styles comes to full fruition on ‘UV Ray’, which, in old money, brings Side 1 of the album to a close. Containing some of William Reid’s heaviest riffing, his guitar and amp also indulge in truly demented flights of fancy that resemble a battalion of chainsaws powering their way through sheet metal. Taken in isolation, it’s a thoroughly unpleasant sound, but this is another fine example of their blending the bitter with the sweet. And the track’s bedrock is an ominous, electronic throbbing that could easily be an out of control helicopter.

That electronic throb is subtly palpable on the stone cold classic that is ‘Blues From A Gun’, the first single to be lifted from the album. An outrageously filthy excursion into rock & roll’s more seedy territories, it pushes, pulls and teases as it holds back before shooting shards of guitar with nary a concern for personal safety.

But it’s on the 12” single version’s flipside where the eyebrows are raised in interest. With the bass guitar replaced by its sequenced counterpart, the rhythmic dynamic of The Jesus And Mary Chain is given a whole new makeover. This is where the implicit acid influence makes itself felt. Witness the gentle yet insistent throb of ‘Shimmer’, a blues-inspired number not a million miles away from the corner occupied by Spacemen 3 on The Perfect Prescription. That same throb is dialled up on the bopping ‘Subway’ and truly adds zest and verve to the salacious ‘Penetration’.

As with all of their best B-sides, much head scratching occurs while pondering how ‘Penetration’ didn’t make the album’s final cut. No matter, for here the Reids deploy skittering synth effects, whooshes and unholy amounts of reverb. One suspects this is the sound Sigue Sigue Sputnik were so desperate to capture. As evidenced by later material such as ‘Birthday’ and ‘Virtually Unreal’ on their misunderstood and under-rated 1998 album, Munki, The Jesus And Mary Chain made the connection south of the hips between electronic music and rock & roll. And it was to ‘Penetration’’s synth throbs to which they took the stage when Automatic went out on tour in 1990.

Crucially, Automatic isn’t an indie-dance album; it’s a rock & roll record that’s plugged in to what was going on around it as it headed for the dancefloor. Though it isn’t totally successful in its objective, the album is nonetheless characterised by a healthy curiosity and sense of experimentation in how rock & roll can be given a contemporary jolt without losing its very soul. Is it a stretch to label this album and the subsequent Honey’s Dead as The Jesus And Mary Chain’s Disco Years? The songs contained on Automatic are always the moment that their gigs to this day are infused with that extra zap to get the last of the stragglers moving.

Though it failed to create the same critical buzz as its predecessors, Automatic’s stock has risen since its release 30 years ago. Part of the reason for this is that, seen in the context of a body of work that’s only recently begun to expand again, The Jesus And Mary Chain never released the same album twice. Each one has a unique personality and sound and Automatic was the moment they made sense of the contemporary tools that would see them through until their implosion at the tail end of the 90s. But perhaps the biggest reason in its rehabilitation is simpler than that: it’s a record that you can dance to. And in rock & roll terms, praise doesn’t come much higher than that.