In many ways, Oil On Canvas is something of an odd swansong for a band that were, in this writer’s opinion, the most fascinating of the late-seventies and early-eighties “synth-pop” acts, if Japan can even be described as such. By the time 1982 rolled towards its conclusion, the quartet’s long slog towards recognition and success -which had seen them bang heads against the wall since 1978’s ‘Adolescent Sex’- had been spectacularly rewarded with the surprise chart success of 1981’s Tin Drum and its slow-crawling single ‘Ghosts’, performed with icy detachment on Top Of The Pops in March of 1982 on its way to number five in the charts. Lead singer David Sylvian had even received the dubious crown of “most beautiful man in pop”. Most bands would have received this belated adulation with relish and milked it for all it was worth, but for Japan it represented a final flourish, as Oil On Canvas was recorded live a month before they parted ways and released posthumously in June 1983.

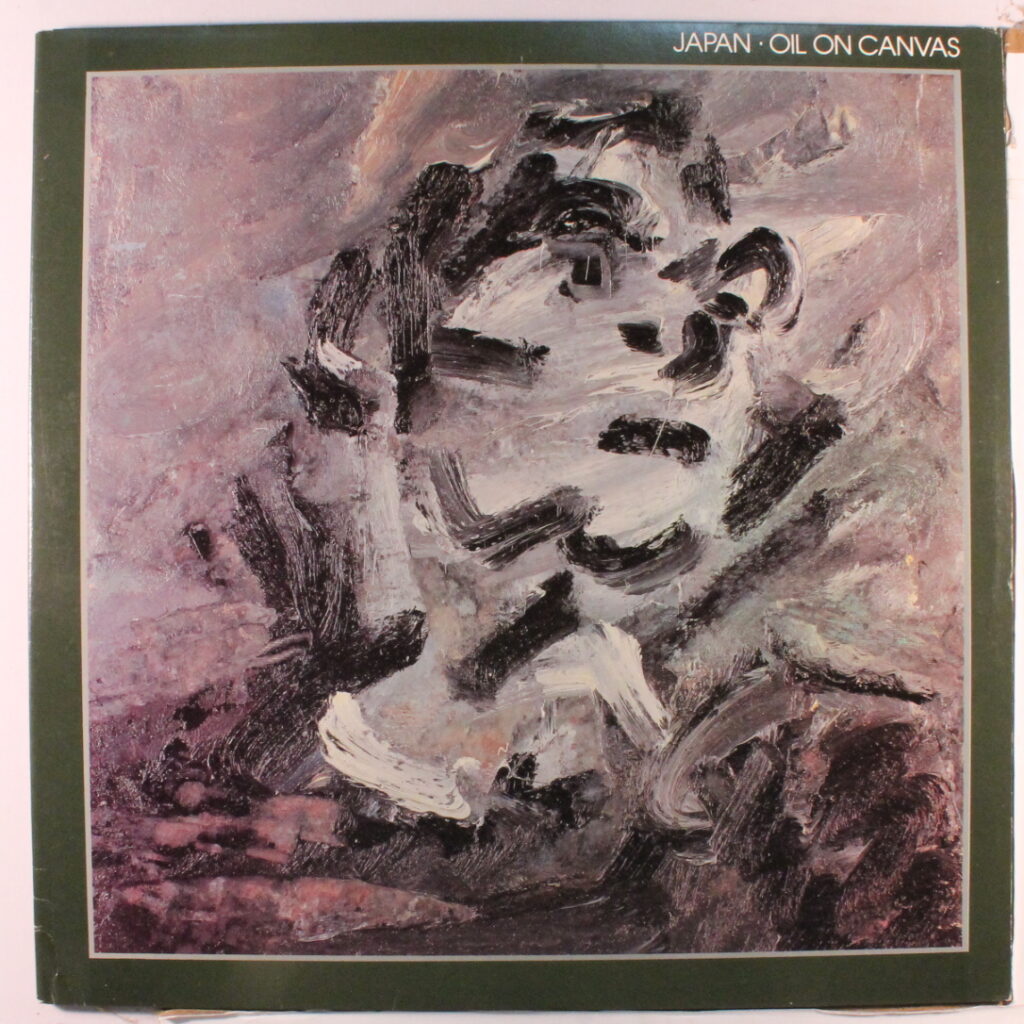

Oil On Canvas is not just odd because it caps a fine musical catalogue with a series of familiar songs played live, but also simply because it is a concert recording. Much had been made of Japan’s somewhat impersonal stage presence over the years, so to decide to bid farewell with a live album could have been the ultimate wet fart of a climax. Maybe for some, it was. For me, Oil On Canvas crystallizes what was so brilliant about Japan in one neat statement. Tin Drum and Gentlemen Take Polaroids might be their definitive works of art, but, if anyone I know asks me where to start when deciding to explore Japan’s oeuvre for the first time, I generally point them towards this (beautifully-packaged, it must be said) double album and film (now available on DVD). The criticism might have something to do with the lack of stage banter or pyrotechnics one usually associates with a live album, at least those of us used to iconic rock statements such as Live At Leeds by The Who or Slade’s Alive!, but that misses the point somewhat. Japan never intended their music to be mere sweat-inducing, high octane entertainment. Even during their early days as something of a punk-glam hybrid, they, and especially Sylvian, were too thoughtful, too introverted to get a crowd pogoing like dervishes, as they quickly found out during a disastrous tour supporting Blue Öyster Cult.

The synthesizer fervour that gripped Britain in the wake of Kraftwerk and The Human League’s late-seventies output was particularly beneficial to Japan, who, seemingly overnight, ditched the platform boots and wild hair, refined their make-up, slowed down their sound to take in swirly synth textures and loping fretless bass, and emerged in 1979 with Quiet Life, an album that pushed the elegant, improbably-coiffed Sylvian into the limelight, aided and abetted by some of the band’s best songs, such as the pleasingly camp title track, the driving ‘Fall In Love With Me’, the ice-cold ‘Despair’ and a delightfully rigid take on the Velvet Underground classic ‘All Tomorrow’s Parties’. Quiet Life deserves to be placed alongside Travelogue, Mix-Up and Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark as one of the key early British synth-based pop/rock albums, as it defined a very European form of detached, sexually-ambiguous and thoughtful art-pop, one not too dissimilar to what the ever-prescient David Bowie had delivered two years earlier with Low.

Quiet Life became a springboard to send Japan into radically bold new territory. The album followed its two predecessors in garnering very little interest in the UK, but Sylvian’s beautiful features, tight-fitting suits and elegant quiff helped make them stars in the country that gave them their name. Struggling to get noticed at home, they could fill the Budokan in Tokyo, and this exposure to a brand new culture seemed to fire Sylvian’s synapses, as 1980’s Gentlemen Take Polaroids took the sound of Quiet Life and refined it into a series of oblique, almost cinematic avant-pop creations that exquisitely surround the frontman’s woozy post-Bryan Ferry croon in layers of pop textures that sounded like little else by Japan’s contemporaries. As well as Sylvian, Japan featured the talents of his brother Steve Jansen on drums, a polyrhythmic genius behind the skins, the late, great Mick Karn, whose bouncing fretless bass made Japan instantly recognisable and was also a dab hand at the sax and clarinet, and the increasingly moody and atmospheric ambient synth flourishes of keyboardist Richard Barbieri. Together, they transcended the very notion of “synth-pop”, rendering the term completely useless as a way of describing towering, crystalline mini-masterpieces like ‘Methods of Dance’, ‘Swing’ and ‘My New Career’. Only guitarist Rob Dean was an uneasy fit in Japan’s meticulous form of synergy, and he promptly left before the band recorded its masterpiece, Tin Drum, in 1981.

Too much has been written about Tin Drum for me to be able to really add to its reputation. Suffice be it to say that it is unique in pop history, a fearlessly ambitious, unusual and conceptual work of art that defies genre categorisation. That it became a hit and spawned a top five single, makes it all the more startling, because I doubt there are many hit records this chart-unfriendly. But tensions within the band, and David Sylvian’s increased hostility to the limelight spelled the end for Japan just as they were becoming huge, leaving Oil On Canvas with the unenvious task of seeing them off in style. Which it does, even if it could never come close to matching Tin Drum for brilliance (it features most of that album’s tracks after all), and will surely therefore be condemned to be viewed as an afterthought by a band whose singer’s mind was already on his (marvellous) solo career.

But if you watch the film that accompanies Oil On Canvas, and was recorded at the same concert, it’s clear that Japan weren’t the sterile live act many have claimed. They were no Sex Pistols or The Clash, but their demeanour suits the music they play to a tee. You can almost hear women (and probably some men) in the audience swooning as Sylvian strides onto the stage midway during the lugubrious ‘Sons of Pioneers’, and the man looks like a suave android in his neatly tailored grey suit, peroxide blonde hair barely moving as he sways in front of the front row, his sensual voice caressing the senses. Mick Karn performs weird crab-like dances as he thumps his bass, sliding to and fro across the stage, whilst Barbieri remains statuesque and impervious behind his banks of keyboards. Perched above them all, Steve Jansen cuts a cool figure behind his kit, earphones sitting on his head to make sure he doesn’t miss a beat. Joining the quartet is guest Masami Tsuchiya to flesh out the tracks with guitar, keyboards and tapes. On each track, they are all bathed in subtly-applied lighting of various colours, the beams glinting off the neck of Karn’s bass. He and Sylvian captivate the most, their gentle movements coming on like a restrained choreography based on kabuki theatre. Oil On Canvas, as a performance, enhances the status of Japan’s music as the most perfectly-realised combination of east and west inside a pop format. It’s no wonder the band, and Sylvian in his solo career, would work so much with the likes of Ryuichi Sakamoto, Yukihiro Takahashi and Tsuchiya.

Highlights abound, from the early twin onslaught of ‘Gentlemen Take Polaroids’ and ‘Swing’, the former bleeding into the latter via moody, rumbling synth ambience; through a rapturously-received rendition of ‘Ghosts’; blistering takes on ‘Still Life In Mobile Homes’ (with stirring guitar noise from Tsuchiya) and ‘Methods Of Dance’; and culminating in a rousing finale of ‘The Art of Parties’, all of which combined make me feel very jealous of the Hammersmith audience. Critics will moan that the songs are almost note-for-note recreations of their studio counterparts, and I agree that the film is the better medium to absorb Japan’s curious form of stagecraft, especially as it is bolstered by gorgeous abstract footage of Chinese life and scenery, but I think hearing such beautiful music with the added cheers and applause only enhances the tracks. It should also be noted that there’s a bit of sly humour at play on Oil On Canvas, as three studio instrumentals, composed by Sylvian, Jansen and Barbieri are dropped into the tracklist, as if the band is deliberately blurring the lines between stage and studio. I’m sure they were well aware of their critics’ complaints, and maybe the title track, ‘Voices Raised In Welcome, Hands Held In Prayer’ and ‘Temple Of Dawn’ are their way of pointing out that they don’t give a shit. They also serve to point in the direction Sylvian and, to a lesser extent, Jansen and Barbieri (as Dolphin Brothers) would take after Japan had been disbanded.

Oil On Canvas is ultimately an oddity because it serves as both a great introduction to Japan, and as the final chapter in their existence (discounting Rain Tree Crow). As such, it has a strong emotional pull for the Japan fan, and offers a neat way in for the rest of the world. It’s probably not an essential record, as I noted, but it’s a damn fine one by a damn fine band.