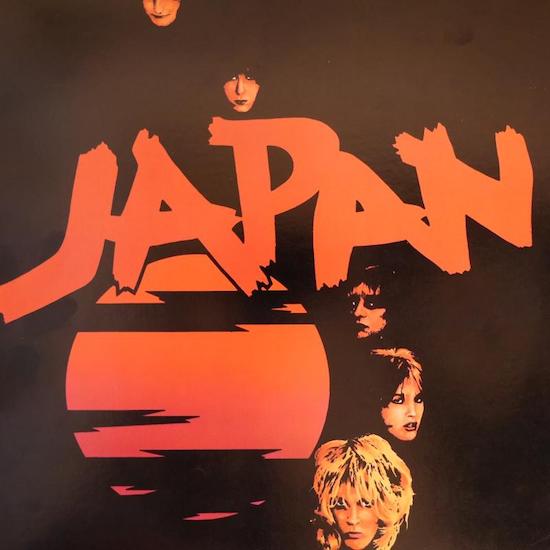

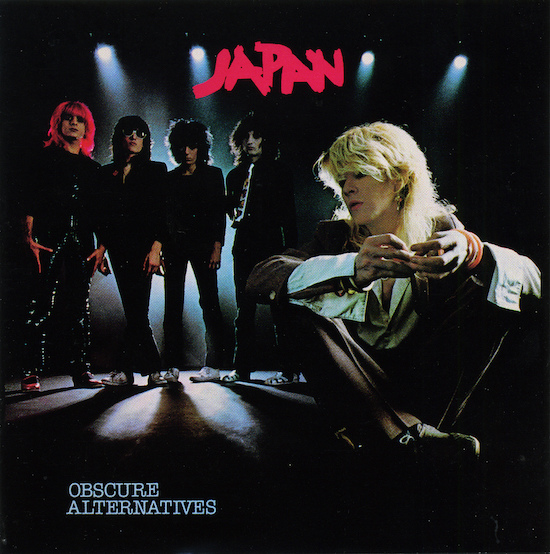

It’s forty years since Japan released their 1978 debut album, Adolescent Sex. Just six months later they followed it with Obscure Alternatives. The body heat of these records is not the temperature most think of when they think of Japan. The band evolved, and became the epitome of cool elegance and elegiac electronica. Sparse, austere and melancholy are the last words you’d use to describe their debut and its successor, which took a randy sledgehammer to subtlety. They are abrasive, strutting, gobby, in-your-grill slashes of glam-punk-sleaze-funk, and pretty much everything the personnel, then aged around twenty, grew to aesthetically oppose. Yet here’s the thing: diehard fans absolutely love them. If loving them is wrong we don’t want to be right. This isn’t to say we don’t far prefer the later work: I mean, we’re not animals. But – to rip off Oscar Wilde – every saint has a past, every sinner has a future. Even a monk after a Damascene conversion surely retains a sneaking private fondness for his youthful rapscallion days. Their contrast with the refined air of, say, the matchless ‘Ghosts’, is healthy, invigorating. Hearing Japan’s formative visceral raunch is as much compulsive fun as watching Grace Kelly twerk.

Needless to say, Grace Kelly doesn’t like to talk about the twerking.

I was interviewing David Sylvian for a career overview in 2004 and suggested we work though album by album, beginning with Adolescent Sex and Obscure Alternatives. “You can,” he shrugged politely. “I mean, I haven’t heard them since 1982 or whatever. I have no interest.” He wasn’t being rude or affected. He genuinely doesn’t see what he perceives as juvenilia being relevant to his body of work. On another occasion I asked him if he hated them as much as is generally made out. Can he not even hear them as youthful, buoyant “fun”? “I don’t cringe as much as I laugh,” he said, smiling. “I don’t take it so seriously as to worry about it. I understand the train of thought. It doesn’t bother me.”

Richard Barbieri, Japan’s keyboardist and synth seer over their relatively brief but still-resonant career, today says, “I could look back and accept and even appreciate a crude or tasteless approach if it had the seeds of my/our personality, or musical DNA. But I really don’t think the first album has that. It doesn’t have many original or creative moments. I can much more relate to Obscure Alternatives, and were that the debut album I would’ve been quite pleased.”

Grace – sorry Japan – are far from alone in such distancing and revisionism. Scott Walker won’t be singing, say, ‘The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine (Anymore)’ again in a hurry. Doesn’t make the song any less perfect, and there are those of us – whisper it – who’ll always find it infinitely more moving and relatable than him bashing a glazed ham with a cattle prod or whatever. Radiohead don’t generally do ‘Creep’ as a crowdpleasing encore. Kraftwerk all but pretend their first three albums don’t exist. Lou Reed panned Transformer and indeed most of his work on bad days (although on other days he’d proclaim their genius). Lee Mavers disowned The Las album; Green Gartside isn’t enamoured of the early “indie” Scritti Politti oeuvre. REM shrug off Fables Of The Reconstruction, The Smiths moaned about their debut, and Alex Chilton was less than enthusiastic about Big Star’s work. Talk Talk and My Bloody Valentine seem faintly embarrassed by the first things to bear their name, and Kevin Rowland far prefers his recent releases to his Eighties ones. Cocteau Twins don’t think Treasure is gold and Depeche Mode are usually in denial of their perky pop era. John Lennon notoriously shrieked on the Plastic Ono Band album that “I don’t believe in Beatles”, though he was just doing the 1970 version of trolling.

Kate Bush disliked her albums The Sensual World and The Red Shoes so much that she restructured and re-recorded tracks for the ill-advised The Director’s Cut release in 2011. This had the effect of making lifelong fans feel like we were being told we had cloth ears, and that our fond memories were worthless. And that’s the awkward thing when our favourite bands slag off the records which made us first fall in puppy love with them. It feels like they’re telling you you’re a mug. You got duped. (Ever get the feeling…?) Except you didn’t, because what the listener hears is what the listener hears, and therefore you’re right. You’re no more wrong because the source tells you so than you are if some reviewer says your favourite record sucks. The artist is of course coming at it from an extremely subjective position, laced with equal parts hubris and self-doubt. Eugene O’Neill wanted the manuscript to Long Day’s Journey Into Night buried: his widow disobeyed. What did Eugene know?

So our passion for the adrenalised thrill-ride that is Adolescent Sex persists, surviving even that slimy image of the print advert that showed a woman’s hand entering a man’s fly, a promotional ploy of which UFO would’ve been proud. (This was not the band’s doing; one Simon Napier-Bell was then their manager and his head worked in a different realm to theirs.) You just need to hear their camply caustic cover of ‘Don’t Rain On My Parade’ – yes, the princes of New Romantic hauteur bashed their way through a Barbra Streisand song from Funny Girl – to feel your body respond. The track may be the kept-in-the-attic offspring of glam and punk, but it’s just so spry at what it does. Tight, insistent, witty and capable of felling a tree at twenty yards. “I like covers when they’re completely different in arrangement to the original,” offers Barbieri. “And this couldn’t be more different.”

Japan had formed as far back as 1974 in South London, with the brothers Batt (David Sylvian and drummer Steve Jansen; their names revealing their youthful New York Dolls fixation) joined by Barbieri, bassist Mick Karn, and guitarist Rob Dean, who is front and centre on these records and who departed after the music grew more European and electronic over the next two albums, Quiet Life and Gentlemen Take Polaroids.

Flamboyant of sound and look, working-class Bowie-Roxy kids, having at last got a record deal they released their first two statements at the height of punk, ensuring instant out-of-step unfashionableness and the bile of blinkered critics. Androgynous peacocks were out of vogue in the post-Glam, pre-Blitz era.

“When I left school at sixteen I went to work in a bank for a year,” recalls Barbieri, whose latest album Variants is as ambient and abstract as early Japan were not. “One day I saw David walking on the other side of the road. We knew each other from school but had lost touch. He looked great – white suit, bright red Bowie cut and platform shoes. I’d never given wearing make-up much thought, but when I joined the band it felt quite natural, and we managed to develop a “look”. I was into heavy rock, prog and Krautrock at the time, but eventually it was Glam Rock that became more of an influence.”

Sent out on tour in Spring 78 supporting Blue Oyster Cult, they were (metaphorically) pelted with tomatoes. (By November, a headline tour saw the nascent Duran Duran in the audience in Birmingham, taking style notes). So, getting defensive, Japan got even louder (visually and sonically) as a self-protection mechanism. Napier-Bell pitched Sylvian as “Jagger meets Bardot”. Loathed in the UK, they were met with feverish zeal in, of all places, Japan. There they were hailed as rock gods, and even sold some records. They also picked up a few ideas from outside the Western norm, and these subsequently coloured their musical psyche, which didn’t so much expand as travel intricately inward, contemplation replacing exhibitionism.

Adolescent Sex isn’t just a primal howl of teenage-rampage raunch, however. Its funk is genuinely funky (‘The Unconventional’, ‘Lovers On Main Street’), its bubbling undercurrents of electronica already plotting and scheming a future. “It’s clear that Mick and Steve are already very capable,” says Barbieri. “David has the attitude and Rob the musical theory and skill.” And lyrically Sylvian is getting very busy, a young man already setting the geopolitical arena to rights on such tracks as ‘Communist China’. The second album doubles down, offering ‘Rhodesia’ and ‘Suburban Berlin’. I’d suggest the awareness of world events filters subversively through the piercing riffs, but it’s right there, staring into the camera. Of course, David Sylvian thinks it’s trash. (Note: these albums are undoubtedly trash. They are masterpieces of trash. Warholian, pretty pretty vacant, zeniths of the trash aesthetic.)

“But they weren’t politically aware!” Sylvian all but spluttered at me in the Eighties. “Really! They were just playing with imagery. I get angry sometimes when I get letters from people who like those lyrics, and I think – how can I explain to them that they’re meaningless?”

“I have no idea what the lyrics were about,” confides Barbieri in 2018. “Possibly David articulated similar in interviews at the time. But there are just some great lines in there, like you get with Marc Bolan. And ‘Suburban Berlin’? Berlin was of course the only city without a suburb at the time…”

A curious aside: the producer of these two albums, Ray Singer, had produced Peter Sarstedt’s million-selling 1969 chart-topper ‘Where Do You Go To (My Lovely)?’, written a French number one for Francoise Hardy, worked for Chris Blackwell and played guitar for the original, British band Nirvana. He went on to work with Joan Armatrading and then produce hundreds of TV commercials, including monstrously successful ones for Levis and Guinness.

The band’s biographer Anthony Reynolds, author of Japan: A Foreign Place, believes the band’s inherent spark transcends everything. “In their every expression, some weird aesthetic quirk comes through. On these albums they’re reaching for something so obviously beyond their capabilities that it’s thrilling. The production’s much slicker than the band themselves, which makes for a queer dichotomy, and that’s a paradox I like. And they’re shameless about it, which is mirrored in their appearance. Like all the best bands they were a universe unto themselves. It was a universe which as a fan I wanted to be a part of. Crucially, other people didn’t want to be a part of it, because they didn’t get it. They were missing out.”

Renamed Japan in some countries to reduce controversy over the title, the scarlet-and-black debut wound down, or rather up, in the nine-minute finale ‘Television’, which snarled and sneered over a licentious, locked-in groove. In Japan the country, a mistranslation saw it renamed, with poetic randomness, ‘Temptation Screen’. “As on all Japan albums,” muses Barbieri, “a track or two pointed to a new direction, and I think ‘Television’ had some sonic, punky energy which was explored more on Obscure Alternatives…”

Obscure Alternatives is a more varied beast, not unlike a very good-looking model trying on various hats for size. Ray Singer seems to be up for, and up to, anything. It crackles with presence, its songs about cities and lust gleaming with lens flare. Punk, art rock, white funk and even reggae take turns, like excellent dancers on Soul Train. ‘Automatic Gun’ and ‘Love Is Infectious’ pre-empt post-punk; ‘Sometimes I Feel So Low’ is a depressed pop song in negative. Barbieri relates more to this album.“ It has its moments. It was a different studio experience and we were now more interested in the overdubbing process, experimenting with sounds. More about shaping how the tracks sounded as opposed to just getting the performances on tape. And it reflected the music that interested us at the time. We liked punk – but NOT UK punk. New York punk had more substance and art to it: Patti Smith, Television, Talking Heads, Lou Reed. We also liked reggae – Big Youth, Peter Tosh, Steel Pulse. Plus of course the European Bowie and Iggy albums. So the sound here is harmonically more interesting and the musicians’ personalities become more evident: more ideas, more abstract touches. Interestingly it doesn’t give any clue to the next step. Except maybe for ‘The Tenant’ but I think it’s very different to the lush, layered, orchestral and atmospheric electronica of ‘Quiet Life’.”

‘The Tenant’ is a seven-minute instrumental which mournfully visits Bowie’s Low (Side Two) and parties with Arvo Part and Erik Satie. “All the best albums have a track that’s a kind of preview of the next album,” says Reynolds. “On Obscure Alternatives it’s definitely ‘The Tenant’. Meditative. Drifting with the mood being as important, if not more so, than the structure. A sign of things to come.”

“We were a very self-contained group of people,” Sylvian told me. “So we always felt on the outside… of anything, to an extent. We genuinely did not feel part of any movement or genre. Yes, image and presentation had been important to us from the beginning, but it became something I was less and less interested in sustaining. It had been convenient, given me a persona to hide behind. Initially I don’t think I could have walked onto a stage without that. I was just too shy. A mask got me through it. Once I decided as a writer I wanted to express myself clearly, it had to be done away with. Elegance isn’t something that should be contrived.”

And so the fast and furious became the foppish and fatalistic as Japan creatively mutated. Over the next three years they birthed Quiet Life, exploring Moroder-ish avant-disco; Gentlemen Take Polaroids, where they learned to relax and swing while filtering rainy romanticism through Barbieri’s lush synths and that ridiculously gifted rhythm section (Karn redefining the bass); and Tin Drum, an album so delicately nuanced and existentially poised that its oxygen was surely made from kittens’ paws. As has been documented, not least in Reynolds’ book, the gang fell out to greater or lesser degrees. Yet the music left its spectral footprint.

“I can understand why it took the critics so long to come around,” Sylvian told me, “as it’d taken me a long enough time to find myself. Success came too late for the band, in a sense: we’d been together so long, trying to find our way in the world. We grew up publicly, made mistakes publicly.”

Japan perceived Adolescent Sex and Obscure Alternatives as their growing-up-in-public mistakes, and anyone joining the fan club from Quiet Life onwards, or working their way backwards from the minimal might of unlikely hit single ‘Ghosts’, would be startled at the balls-out bravado of the early emissions. Yet for the early-adopter fan, being told they’re rubbish (as opposed to trash) is like being told you dressed badly as a teenager. Of course you did. It’s a rite of passage.

Asked why the band members don’t like these albums, Reynolds offers, “Who cares? It never meant anything to me if I love something and the guy who made it hates it. I’m the audience, not them. I think everyone bar Sylvian has a soft spot for these albums, and he probably only dislikes them because they don’t match the ideal he has or had of himself. It must be galling if people are perpetually in love with your teenage public “mistakes”, but it’s not going to block their enjoyment…”

“If you do live a whole fantasy,” Sylvian once told me, “become it. You can’t just dip into it. It’s something you have to live out. Then, yes, it can become an art form.” Adolescent Sex and Obscure Alternatives make a curved kind of sense in terms of Japan’s arc towards elevation.

Four decades later we can purport to spend 24 hours a day reading Stendhal in the original French while wearing spectacles made of angels’ bones, but in truth it’s still a joy to wallow in this so-called filth. Such a pleasure may be guilty, but the thrill of transgression is great. The artist may be right, but the listener is always righter. On a gilded throne in Monaco, Grace sometimes heard a primal rhythm, her flawless ear twitching.