“Rock & roll has been really bringing me down lately. It’s in great danger of becoming an immobile, sterile fascist that constantly spews its propaganda on every arm of the media”

David Bowie, 1976

David Bowie supposedly changed musical styles as capriciously as he changed his hairstyles during the 1970s, and yet what’s rarely discussed is how difficult – and even painful – that process sometimes was. In the same way that conventional wisdom told us for too long that disco sucked, or that punk toppled prog leading to some kind of year zero, it has been assumed that Bowie suddenly rocked up in Berlin with Iggy Pop, knocked the drugs on the head, and then made three lauded albums of experimental electronica with Brian Eno at his side. That assumption is as misleading as it is fallacious.

There’s certainly no clear narrative regarding the Berlin triptych, which, depending on how you look at it, couldn’t have happened without one mentioning at least five or maybe six interconnected records, including two under the name of Iggy Pop. The location too, is often far from Berlin, starting on the West Coast of America and ending on the East Coast, taking in studios in rural France and in Switzerland too. Truly only “Heroes” can claim to be a record fully conceived and actualised in the German city among the three recognised Berlin albums.

Perhaps the greatest mystery regarding Bowie’s productivity during the mid-70s is how he managed to make a record as magnificent as Station To Station when he was so far down the road of cocaine addiction, subsisting on a well-documented diet of milk and red peppers. Rumours abounded that he would keep his urine in jars in the fridge for fear an evil magician might put a spell on him (the logic can no doubt be easily unpicked if you’re reading this sober). For immediately after Station To Station, his creativity appeared to be shot through, from the aborted soundtrack of The Man Who Fell To Earth which Nicholas Roeg is rumoured to have kiboshed on the grounds that it wasn’t very good, to early attempts to produce Iggy Pop, who was suffering from a drug-induced madness even greater than his own.

In a legendary Rolling Stone piece with Cameron Crowe, the author records Bowie ranting about Nietzschean übermensch, the fact he hates his own rock & roll albums and that he might have been “a bloody good Hitler… an excellent dictator”. Crowe also sits in on a recording session with Bowie and Iggy in Los Angeles. The former spends nine hours composing, producing and playing every instrument on Iggy’s demo, before allowing his friend to unleash a snarling improv that on paper doesn’t appear to be one of his best.

“Bowie touches a button and the room is filled with an ominous, dirgelike instrumental track,” wrote Crowe, before recounting some of Iggy’s freestyle screaming:

”When I walk through the do-wa.

I’m your new breed of who-wa.

We will nooowwwwwwwwww drink to meeeeeeeeeeeeeeeee”.

“It’s the best thing I’ve ever done,” drooled Iggy, who then disappeared with a girl he’d been trying to get off with, never to return. When he called days later to apologise for his no show, Bowie told him to “go away”. Although the song did apparently make a brief appearance during Iggy’s solo tour of 77 (featuring one David Bowie on keyboard), ‘Drink To Me’ was never released.

Meanwhile one of the tracks that was intended for The Man Who Fell To Earth soundtrack would eventually turn up on Low in substantially different form, as closing track ‘Subterraneans’, an ambient, mostly instrumental track with the cryptic “share bride failing star / care-lines driving me Shirley” lyric. In fact Bowie apparently sent a copy of Low to Roeg on completion with a brief note that said something to the effect of: “This is what I was trying to do.”

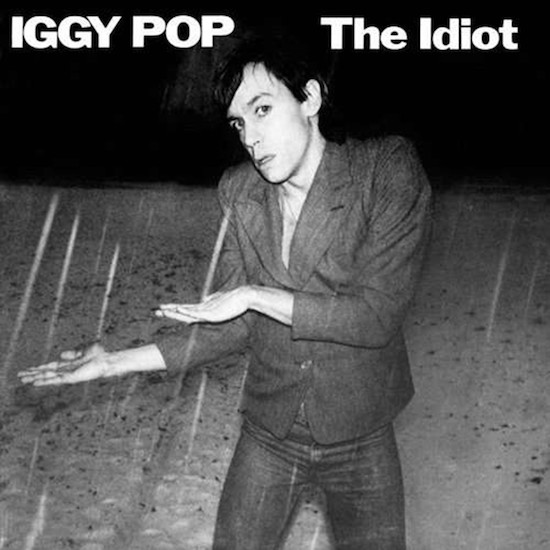

‘Subterraneans’ was perhaps the first track conceived for the Berlin trilogy, and Low appeared in record shops first in January 77 (deliberately tucked away at the start of the year, away from the other big releases) ahead of The Idiot’s March release. Iggy Pop’s debut solo album was actually recorded before Low, and it’s fair to say much of the experimentation that was a feature of the latter started with the former, and not in Berlin, but at the Château d’Hérouville, north of Paris. It would also be fair to say that Bowie delayed release of The Idiot on their shared label RCA, in order that it wouldn’t be seen as the originator – in which case Iggy might be perceived as some kind of cynosure of a new movement. Although it might look Machiavellian in hindsight, Bowie was justified, as The Idiot is a David Bowie album in all but name (Allan Jones of Melody Maker cruelly suggested it was his “second favourite David Bowie album”). With Lust For Life, Iggy took back control, but on its predecessor Bowie directed and played many of the parts, with Iggy appearing at the conclusion of the process of each track as some proto-punk deus ex machina. Bowie was experimenting with a new kind of music, and Iggy Pop was his willing guinea pig. Quid pro quo, it was a deal that benefitted both of them, and suggestions that Bowie was purely manipulating Iggy for his own ends are wide of the mark. (Bowie stepped in in 86 to work with him again on Blah Blah Blah when Iggy was in yet another tight spot; just one example of a friend indeed assisting his frequent friend in need.)

Château d’Hérouville was probably suggested by Tony Visconti, who had recorded The Slider with T-Rex there. For whatever reason, the producer couldn’t quite make the commitment to oversee The Idiot in the end; he would however produce every subsequent Bowie album up to Let’s Dance. The 18th century chateau had been home to Chopin and George Sand, and was said to be haunted by the composer and his paramore. Years later, the country castle had fallen into disrepair, but it was revived in the 60s as a recording studio. Elton John, Pink Floyd, Fleetwood Mac and Gong (amongst many others) recorded albums there, the Bee Gees made ‘Stayin’ Alive’ and ‘How Deep Is Your Love’ at the famous address, while Jean-Michel Jarre once told me he worked there as an assistant when he was younger, where quotidian duties might include preparing treatments for Terry Riley.

Although it’s located not far from Paris in the Val d’Oise département, getting there is actually harder than it looks, and I know because I’ve tried. The recording studio is a going concern again, though the staff are not great at answering their emails (a request to have a look around was met with silence). Located in bucolic surrounds at least 9km from the nearest town – Auver-sur-Oise where Van Gogh and his brother Theo are buried – the only way to get there really is to drive. In other words, it was the perfect location for a couple of recovering misfits looking to avoid temptation and get on with the process of making music away from L.A., a place Bowie had come to loathe, describing it as a “wart on the backside of humanity”.

The record then, thrives from the focus of its creators, with a slightly suffocating, almost underwater quality that comes from the close proximity of those involved, and also the technical incompetencies from working without a recognised hotshot producer like Visconti. ‘Funtime’ is clearly about socialising back across the pond, and written in the first person plural, it demonstrates how joined at the hip the two protagonists were at the time.

“Hey baby we like your lips/

Hey baby we like your pants”.

Bowie’s vocal is high enough in the mix that it could be a duet, at least if the effect on both voices didn’t make them sound like an automaton; the almost mechanical delivery symbolises the ritual of going through the motions when you’re a social butterfly, even if it stops being fun (and then what do you do with yourself if you don’t go out?) ‘Dum Dum Boys’ is inspired by Iggy’s time in the Stooges, while opener ‘Sister Midnight’ – built around a Carlos Alomar riff – actually came into being before The Idiot, played by Bowie on the Isolar tour supporting Station To Station. Intriguingly, Bowie uses the same riff on ‘Red Money’, the final track on Lodger, a rounding off that surely canvases for The Idiot’s inclusion in the body of work. More on that in a bit.

Perhaps ‘Nightclubbing’ is the only track that could reasonably be assumed to have been inspired by Berlin, throbbing as it does with the sleazy ambience of a Kreuzberg club such as Club SO36. Indeed the muffled drum machine that thumps like a slowed down heartbeat almost sounds like it’s coming through the floorboards. “Bowie kept saying, ‘But we gotta call back the drummer, you’re not gonna have that freaky sound on the tape!’” recounted Iggy Pop, “and I replied, ‘Hey, no way, it kicks ass, it’s better than a drummer.’”

The drummer in question was Michel Santangeli, who’d been called over from Brittany, and dispensed with again before he’d barely got his sticks out of his drum bag (it had become a working practice of Bowie’s to get the drums down as quickly and spontaneously as possible and then build the track around it). Santangeli had been brought in by the chateau’s sound engineer Laurent Thibault, who also happened to be Magma’s bass player. Bowie surprised Thibault firstly when it became clear that he was intimate with the prog rock band’s own music, and again when he hired him as bassist for The Idiot. And session guitarist Phil Palmer was brought in and given an unusual brief. According to Paul Trynka’s Open Up And Bleed, he was told to imagine the sounds of different clubs as if walking down Wardour Street, and to replicate the sounds from each as he passed.

It should be noted that regular contributors, drummer Dennis Davis and guitarist Alomar, also appear on the record, and Visconti did some of the mixing back in Berlin as well as Munich, though who did exactly what was left off the sleeve. The cover art itself was inspired by Die Brücke expressionist Erich Heckel’s Roquairol, which hung in the Brücke Museum an hour or so away from Hauptstrasse 155, Bowie and Iggy’s Berlin residence. They’d secured and paid for the rights to use the painting for the cover of The Idiot, but instead went with a photo of Iggy imitating the image instead. Bowie would then do the same himself for the cover of “Heroes” in 1978.

A month’s studio time had been paid for and was now left over at the chateau, and so Bowie reconvened there for the Low sessions, with a crew whose personnel would more or less be present throughout the trilogy, including Visconti and Eno. He’d informed his collaborators that work may result in something or nothing, a Dadaist no programme where the point was to create art for its own sake. Having sought to curb his own nefarious ways, he was suffering from writer’s block lyrically, which is perhaps why he was throwing himself so enthusiastically behind Iggy, and definitely why Low is so short on actual words, and why it fades in and out so often as though it’s an assemblage of clips. The raison d’etre for The Idiot, and by default for Low, echoed the words of the Cabaret Voltaire’s Hans Richter, who wrote that there “was a brief moment in which absolute freedom was asserted for the first time. This freedom might lead either to a new art – or to nothing”.

The Idiot was the dry run for Low, and against the odds, it had turned out to be a great album. Ditto with Low, which in turn was the dry run for “Heroes”, which was also of the highest standard. If Low explores uncertainty and offers few answers, then “Heroes” forges ahead with confidence, but ultimately its victories are as a result of the toil achieved during Low, which will always be critically more appreciated for doing it all first.

While much of Low – which was going to be called New Music: Night and Day until the last minute – was laid down at Château d’Hérouville, the relationship with Thibault apparently broke down after conditions at the facility deteriorated. Starving after neglectful staff had apparently forgotten to stock the cupboards, Bowie and Iggy both went down with food poisoning from some dodgy fromage. Bowie, Visconti, Iggy and assistant Coco Schwab disembarked for Berlin where they’d finish the album at the "Hansa Studio By The Wall". Lust For Life followed, which was then succeeded by “Heroes”, both recorded in West Berlin. A gap then ensued as Bowie went off to film Just A Gigolo with Marlene Dietrich (although the two filmed their shared scene from different cities). The final piece in the jigsaw puzzle – Lodger – was recorded much later over a six month period between September 1978 and March 1979, firstly at the plush Mountain Studios in Montreux, Switzerland (where Bowie officially lived for tax reasons) and then in New York (where he would settle from 1993 onwards).

Two recent books on Bowie’s time in Berlin – Heroes by Tobias Rüther and Bowie In Berlin: A New Career In A New Town by Thomas Jerome Seabrook – pay little lip service to Lodger. Seabrook dedicates whole sections to song breakdowns not just of Low and “Heroes”, but of The Idiot and Lust For Life too, while neglecting to do the same for Lodger; Rüther meanwhile seems to spend more time on the ill-fated Just A Gigolo than he does on the final album in the series. One can see why. Lodger is a fine album for sure, and an underrated one (or as much as a David Bowie album can be underrated), but its links with Berlin are tenuous to say the least, and not just because it wasn’t recorded there. The personnel might be the same, but Bowie had moved on from his own personal Weimar period, and that’s reflected in Lodger’s international flavour. ‘African Night Flight’ for instance, is based on trips Bowie took to Kenya, while the exploration of rhythm would act as a catalyst for Eno, who would explore such ideas further with David Byrne on 1981’s My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts. And speaking of moving on, it would appear Eno and Bowie had done just that, from each other, though they’d come together again on 1995’s 1. Outside.

For all of the above reasons, The Idiot has a greater claim to being one of the Berlin three in preference of Lodger in my opinion, though perhaps it would have been disrespectful to Iggy Pop to regard it as such, given that it’s his name on the record. Carlos Alomar said many people felt “they were due a trilogy”, according to David Buckley’s Strange Fascination, but perhaps they’d already been delivered one without realising it. If Lodger is a Berlin album then so is The Idiot, so should it perhaps be a Berlin tetralogy with some French flavour? And while Iggy seized back a little control on Lust For Life, it’s difficult to imagine some of the quickfire lyrical improvisations that Bowie laid down on “Heroes” had he not been inspired by Iggy working on Lust For Life in the first place. “Bowie’s a hell of a fast guy,” complained Iggy later. “I realised I had to be quicker than him, or whose album was it gonna be?” Also take your mind back to the intense crooning on, say, ‘Wild Is The Wind’, and compare it with the deep sprechgesang delivery on Low; that could only have really been inspired by Iggy’s vox on The Idiot. These albums are all intertwined, so should we look at them as a Berlin pentalogy? Whatever you might decide, Lodger is without doubt the most anomalous of them all.

Perhaps before we leave this discussion, I should point out that the Berlin triptych never was official, and you’re free to compartmentalise records as you see fit. Or perhaps, as Bowie’s old friend Lou Reed proved, Berlin is simply a state of mind. Having never been to the city himself when he wrote the titular chef d’oeuvre, it could be argued that Berlin, or Berlin, is simply a symbol of decadence and faded glamour rather than somewhere situated in reality. Bowie once described it as the “greatest cultural extravaganza that one could imagine”, while the (little known outside of France) former French minister for culture Jack Lang said it best when he said, “Paris is always Paris, and Berlin is never Berlin.”