One Friday evening a couple of years ago, my phone began to ring. In the time it took me to dash up the stairs and locate its dulcet tones I’d missed the call and the number was showing as ‘blocked’. I had a flutter of panic – twenty minutes later I was due to interview rap legend Ice Cube by phone. Surely I couldn’t have missed his American record label’s call? When dealing with musicians nothing is ever early. Ever. It was too late to call his UK publicist – he’d be out doing whatever it is young, hip dudes do on a Friday night in Dalston – so I mouthed a silent prayer for the phone to ring again.

Ten minutes later (and still ten whole minutes before the allotted time) my phone began to chirp. I instantly snatched at it and was greeted, in a familiar Californian drawl, with the following one-liner – “Hey John, this is Cube.” I believe more seasoned hacks are steadfastly ambivalent towards interactions with the great and the good of the music world. But, fuck it, Ice Cube’s opening line to me was the coolest thing I’d ever heard in my life. It’ll undoubtedly stay that way unless Prince one day decides to leave me a witty voicemail message.

Cube was promoting a new album (the decidedly turgid I Am The West) but, as a fan of his music since the late 80s, I really wanted to ask him about past glories. Like most Brits, I first became aware of Ice Cube in 1988 when his band N.W.A. released their astonishing debut album Straight Outta Compton. He always seemed the most cerebral member of N.W.A. and when he left the band in 1989 (“having the courage to leave was the biggest decision of my career,” he would tell me) I followed his progress via an unflinching solo debut (1990’s AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted) and a hugely impressive first foray into acting (as ‘Doughboy’ in the brilliant, John Singleton-produced movie Boyz In The Hood).

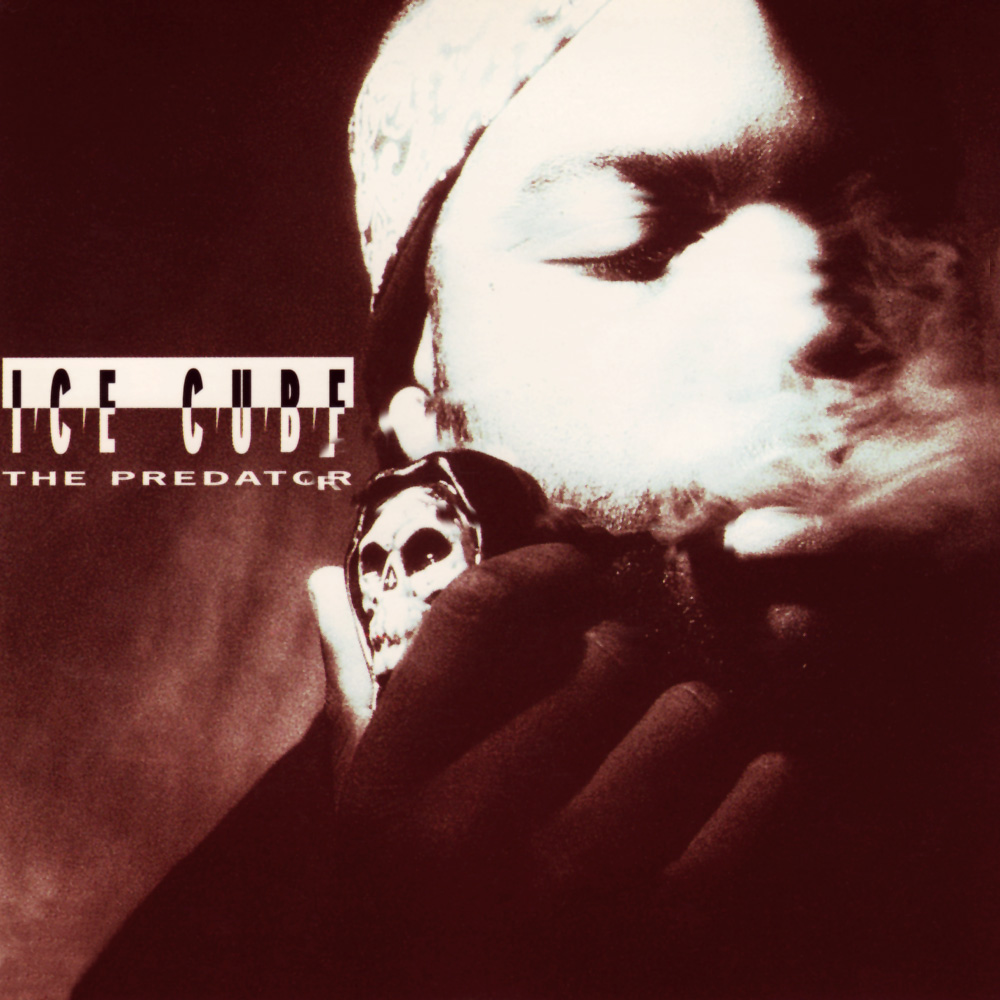

However, it was Cube’s third solo album, 1992’s The Predator, that would become one of my favourite albums of the decade. It was a record fuelled by rage at the acquittal of four policeman accused of beating up a black motorist, Rodney King, even though the act had been clearly caught on videotape. It was the same rage that subsequently sparked six days of rioting in Los Angeles. Ice Cube recorded songs both before and after the riots – making The Predator a thrilling and intoxicating journey.

It also made it a difficult listen. In 1992, I was young, white, middle-class and utterly clueless about life in South Central, Los Angeles. Even though I had grown up a mile away from Manchester’s Moss Side riots of 1981, the world described by Ice Cube, Ice-T and other West Coast rappers seemed terrifying. I loved the music but I also loved the resolve in a message which I interpreted as ‘this is what is happening in our community, do not ignore us’. But, many aspects of the album made my liberal heart squirm. Much of The Predator was hugely misogynistic, while certain songs didn’t do enough to distance Ice Cube from previous accusations anti-Semitism and racism towards L.A’s Korean community. I found these aspects hard to defend, but – compared to the vanilla morality of other music I listened to – believed there was something hugely important about the records Ice Cube was making. In one sense, I enjoyed the intellectual and moral assault course of being a fan.

Indeed, Ice Cube had been central to my own little (albeit indirect) moment of music controversy. Back in 1989, my girlfriend at the time was one of the main DJs at Leeds University Student’s Union. At one ‘Thursday Bop’ (a sonically-grim evening primed with ‘classic’ student floor-fillers) she played ‘Fuck Tha Police’ by N.W.A. The daughter of a policeman was in the crowd and was so offended by the track that she wrote a letter of complaint that was published in the weekly student newspaper (those were seriously quaint times). My girlfriend reacted to ensuing ‘uproar’ by playing ‘Fuck Tha Police’ twice the following Thursday. I still do a mental ‘fist pump’ every time I recall that story.

Ice Cube began recording The Predator in early 1992 but the album took on a completely different direction in the wake of the six days of rioting in Los Angeles which began on April 29. The riots were sparked by the acquittal of the four policemen and, like most people, Cube was deeply disturbed by the verdict.

“It affected us because we felt like we couldn’t get any justice,” he would tell me. “It was inhumane, letting those guys just walk. We all felt in our hearts that these dudes were gonna be found guilty, as we had it on videotape and that had never been the case before. When it didn’t happen everyone was shocked, then surprised, and then mad.”

The subsequent songs perfectly reflected Cube’s disbelief and anger. Be it the wide-eyed terror of ‘When Will They Shoot’, the call-to-arms of ‘We Had To Tear This Mothafucka Up’ or the re-enactment of the King beating on ‘Who Got The Camera?’, huge swathes of The Predator graphically documented the events of the previous months.

“You know ‘It Was A Good Day’ was on that record,” Cube reflected, reminding me of perhaps his best-known solo song. The track loped along at a gentle pace as the rapper recalls a peaceful 24 hours in the ‘hood (“I didn’t even have to use my AK/ I’d say it was a good day”) and was an insight into how The Predator could have sounded if the policeman had been found guilty. “That album had got deflected in a lotta ways; it was on a different tack until the verdict happened.”

Instead, a fully-focused fury was unleashed. ‘It Was A Good Day’ was stopped abruptly by the jarring magnificence of ‘We Had To Tear This Mothafucka Up’, the album’s most direct response to the verdict and Cube’s examination of the ensuing civil unrest, which he maintained had been predicted numerous times by on his previous output. The Predator is one of the angriest records I have ever heard and its energy remains undimmed.

Musically, The Predator still sounds as gripping as it did in 1992. Ice Cube had moved away from the harsher cut-ups and a reliance on scratching of his previous work and extended his palette of sampling sources. The record is downright funky in places, as Ice Cube showcased his love of Parliament and Funkadelic (Cube would confess to me that the only ever time he had been star-struck was when he met George Clinton) – check out the delirious mashing of three Parliament tracks on ‘Dirty Mack’ or the grooved loop on ‘Who Got The Camera?’ borrowed from Funkadelic’s ‘I Gotta Thing, You Gotta Thing’. The album would dip into older soul classics; ‘It Was A Good Day’ used excerpts from The Isley Bothers and The Staple Singers, while elsewhere samples from Sly And The Family Stone, Solomon Burke, Public Enemy, Queen and even Bel Biv Devoe would all add to the glorious sense of sonic adventure.

And Ice Cube called on a stellar cast to fine tune The Predator to the max. DJ Muggs from Cypress Hill produced a number of tracks including the twitching paranoia of ‘We Had To Tear This Mothafucka Up’ and the colossal ‘Check Yo Self’, while Jamaican rap artist Don Jaguar added the ragga refrain to the writhing pulse of ‘Wicked’. Cube also called upon DJ Pooh (who’d previously worked with LL Cool J) and his old C.I.A. collaborator Sir Jinx and this willing inclusivity gave The Predator a vast sense of scope and ideas. The record also features a number of shorter ‘insert’ tracks which include snippets of Cube’s radio interviews (on the unwavering ‘Fuck ‘Em’) and speeches by Malcolm X and Louis Farrakhan. The effect of these interludes is unerring – Ice Cube would not be shifted from his world view.

However, The Predator was hugely controversial. His previous album Death Certificate included a track called ‘Black Korea’ on which Cube outlined the tensions between the black and Korean communities in Los Angeles and unleashed the tide of condemnation for its seemingly racist overtones, while the bleak ‘No Vaseline’ contained disparaging comments about N.W.A.’s former manager Jerry Heller that were viewed in many quarters as being anti-Semitic. On the The Predator, Cube wasn’t exactly brimming with remorse – ‘We Had To Tear This Mothafucka Up’ contains the lines “Regret it – nope, said it – yep/ Listen to my big black boots as I step.”

From my personal perspective, I still wrestle with this moral conundrum. Rappers like Ice Cube were holding up a mirror to the society they knew. I have no doubt that there were huge tensions between certain ethnic groups in L.A. in 1992. However, a song like ‘Black Korea’ – written by a then global rap icon – would surely only fan the flames of mistrust. Personally, it feels naive to argue otherwise. However, I would also defend a musician’s right to make a socio-political comment via their music – so back around the moral maze I step.

What was harder to reconcile, however, was the almost constant stench of misogyny that runs throughout The Predator. Two adjacent songs exemplify the problem – ‘Dirty Mack’ outlines Cube’s use and abuse of ‘hoes’ while ‘Don’t Trust ‘Em’ is a shockingly sexist tale on which Cube complains that “bitches all over on some new improved shit.” It’s depressing nonsense. O’Shea Jackson, as he is known to her, had, by all accounts, a good relationship with his mother. In 1992 he had recently gotten married and employed – unusually within West Coast rap circles in the early 90s – a woman for a manager. His life was clearly enhanced by the women he loved and undoubtedly respected. I am at a loss to understand Cube’s line of logic.

Therefore, while I can begin to try and recognise that the simmering tensions within districts like Compton or Inglewood may explain the bigoted comments on a track like ‘Black Korea’, I cannot accept any defence for the crushingly oppressive portrayal of women on The Predator – the album is poorer for it. I will own up to not questioning Ice Cube about his views on women during our interview. I was a coward.

The Predator was released on November 17, 1992. It went straight to the top of the US Billboard chart and would sell over 3 million copies worldwide. For me, despite my continued issues with key aspects, The Predator is one of the finest rap albums of all time. Great art should define a certain period or a particular mood – The Predator brutally outlined the post-riot landscape of Los Angeles. At the time, Lollapalooza tour buddy Perry Farrell would call Cube “the black Bob Dylan.” Twenty years on, it’s hard not to contrast The Predator with the UK’s musical output post our 2011 riots. Instead of anything as bold as Ice Cube’s flawed masterpiece, we got a lecture on hoodies’ rights from Plan B on his Ill Manors album. I know which I prefer.

In 2012, Ice Cube’s best solo album remains an essential listen. Back in 1992 it made me think – long and hard. It still does.