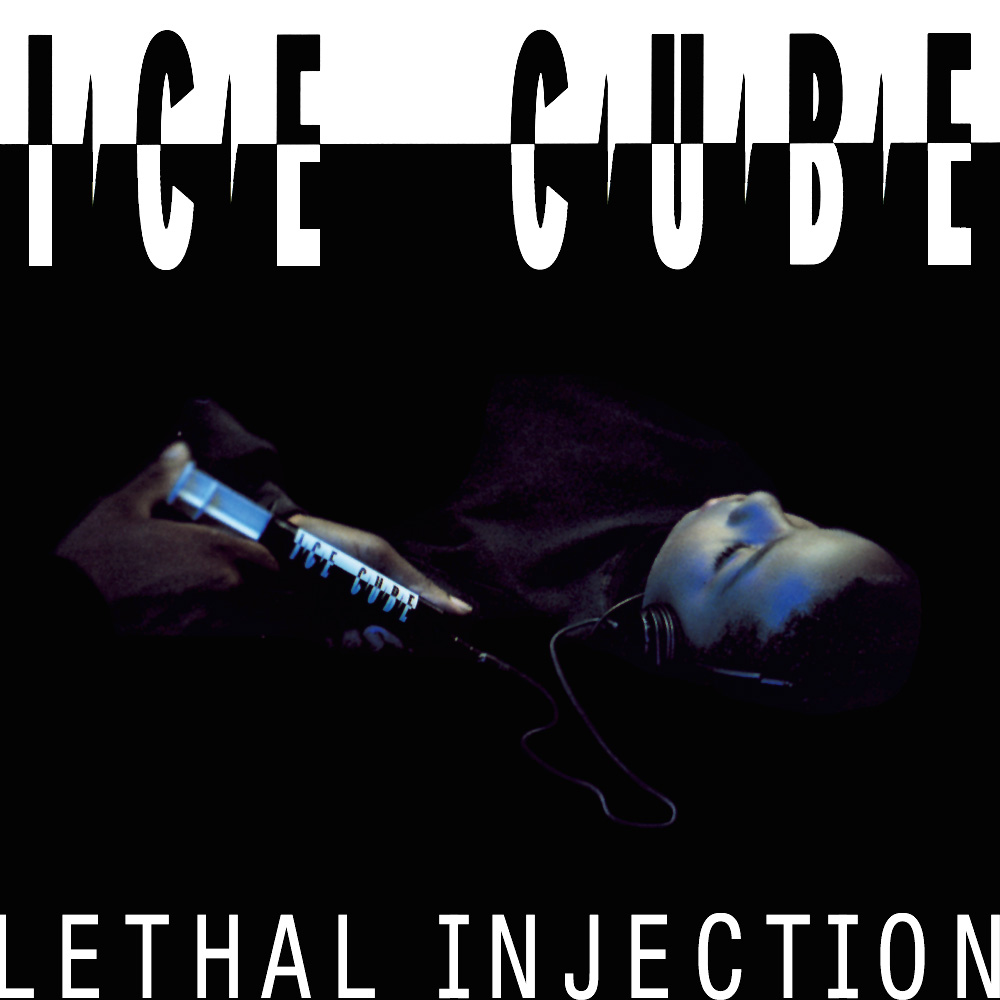

In the interviews he gave at the time, Ice Cube claimed that the primary motivation behind his fourth album was to prove that he hadn’t gone soft. Coming from the maker of some of the most deliberately provocative music ever committed to tape, and following up a release that contained some of his most outspoken material, the sentiment at first glance simply doesn’t compute. But there was legitimate substance to the rapper’s defensiveness.

By 1993, Ice Cube wasn’t just that guy out of NWA who’d written most of Straight Outta Compton‘s unprecedentedly shocking lyrics – he was a rising power in Hollywood; and, much to his evident discomfort, every time he released a record, no matter how hard he worked to wind up every conceivable section of his listenership, his audience just kept on growing. Against all the odds, Cube was a pop star.

He’d followed Death Certificate – a calculatedly offensive album which US record industry trade magazine Billboard‘s editor, Timothy White, claimed "crosses the line that divides art from the advocacy of crime" – with The Predator. That 1992 LP found him delighting in goading his growing army of detractors while gleefully essaying revenge fantasies of Jacobean proportions. It was a record filled with equal parts

indignation and vindication. Look at it from his perspective: had he not spent most of his meteoric career warning of the simmering tensions between black citizens and racist cops in gang-ridden South Central Los Angeles? Wasn’t the physical and emotional devastation wrought on the city following the shock acquittal of the four LAPD officers who had been videotaped beating an unarmed black man into unconsciousness precisely the kind of societal apocalypse his bellicose art predicted? And hadn’t his critics ignored his prophecies, preferring instead to call him a bigot, a

racist, an extremist?

"I told you what would happen and you heard it, read it/ But all you could call me was anti-Semitic," he spat on The Predator‘s opening track, ‘When Will They Shoot?’ – a dirty, delighted, yet paranoid stomp based around samples from X-Clan and Queen. "Regret it? Nope. Said it? Yep." A few tracks later he’s telling us that "riots ain’t nothin’ but diets for the system," and by the end of side one is imagining, in graphic detail, what he’ll do if he gets his hands on the cops that beat Rodney King, before taking his gun and heading out to Simi Valley, knocking on doors, looking for the members of the jury.

The Predator might have been many things, but evidence of Cube repositioning himself as a family-friendly teddy bear of a rapper wasn’t one of them. Yet what it did do was bring him unprecedented success. Death Certificate had been a big hit, and he hadn’t exactly gone unnoticed as a member of NWA. But The Predator – the first album to go straight to the top of the Billboard R&B and pop album charts – turned him into a musical superstar. In no small part this was down to the success of ‘It Was a Good Day’ – the one track it contained which could be released as a single without editing, and which was thus able to garner massive amounts of airplay.

On that song, Instead of writing about the death and the drama, Cube wrote about going round to play craps with your mates, having a drink, getting off with a girl, and making it back home to bed without anyone getting shot: and by emphasising the mundane and everyday as noteworthy, he shone an even brighter light on the darkness he had, for three minutes, ignored.

The fact that ‘It Was a Good Day’ was, in its absence of gangsta stories, a searing critique of black LA’s traumas was largely lost. Its laid-back grooves were, amid the Dre- and Snoop-popularised G-Funk era, as definably Californian as a Beach Boys surf anthem. It was made for the radio. It was pop. Ergo, to some observers, Cube wasn’t the hardcore don any more. It’s all too easy to be wrong, but it’s pretty tricky to be that wrong.

So the biggest surprise about Lethal Injection, an album supposedly created to show mistaken onlookers that his stardom was not cravenly sought, is that the only time it repeats any of the Predator formula is in making what is clearly a quite deliberate ‘It Was a Good Day Part Two’. ‘You Know How We Do It’ is almost identikit – albeit given an even glossier, even more lush backdrop by the consistently excellent Quincy Jones III and his inspired Evelyn "Champagne" King sample. You can stick it on next to any of Dre’s Chronic hits and it stands its ground – a perfect slice of synth-laden G-pop, with Cube at his most

languidly beguiling. It’s pretty much the only moment in his entire on-record career where he’s to be found repeating himself: the skilful part is that he does so without diminishing the returns.

That – and an eleven-minute reworking of George Clinton’s ‘One Nation Under a Groove’ in the company of the captain of the Mothership himself – apart, the album is every bit as angry and as provocative as anything in Cube’s discography. The only real difference from the three previous solo LPs is that it’s a bit shorter. Maybe he learned editing from his burgeoning film career: certainly he seems to have taken something from the screenplays one imagines made up the majority of his reading material during the parts of 1993 he spent working on this record.

It was LL Cool J, that supreme master of the brag, who wrote: "My tongue is like a chisel and this composition’s sculpture," but there are few rappers whose microphone presence is more physical than Cube’s. His voice is a remarkable instrument, one of 20th century music’s most distinctive, but on Lethal Injection he allied it to a style of writing which emphasised both the skilled film-maker’s ability to excise all but the most vital image, and the poet’s relish in making a small number of words

carry the weight of entire chapters.

History, as yet, does not record precisely who was taking notes: but you can detect this style’s presence, whether deliberate or accidental, in a number of later records. Nas, who chose rap as a teen because he felt making a record was a more realistic ambition than getting to turn the film scripts he was writing into a finished movie, is one artist who has honed similar writing skills. Ghostface and Raekwon have also written many verses where what you hear are less lyrics than minimalist notes describing vivid images which quickly cut from one to another. Maybe they would have done that even if they hadn’t listened to Cube, but Lethal Injection feels like one of

the earliest examples of the practice.

Take the opening track, ‘Really Doe’, where a deliberately sparse, toughened beat is surmounted by portentous echoing samples from the Pointer Sisters and rumbling, ominous bass, and watch/listen to the flash-cut of verbal pictures Cube fashions from a daringly limited number of words. "If you got a herringbone/ Welcome to the terrordome," he says, almost with a chuckle as the three-syllable rhyming words toddle around in

triplets, inviting well-dressed outsiders into an hour of his world of pain and doffing his backwards baseball cap in Public Enemy’s direction while he’s at it. In his storyline, things start to go wrong, so his protagonist heads to the city, a Clinton classic on the car stereo: "Oh my God!/ Gettin’ robbed/ Reach for the smog/ Atomic Dog." In verse two he’s in a

police cell, an old Biz Markie tune lodged somewhere in the back of his head, and you can see, smell, feel, almost taste it: "Thirty in a holdin’ tank, catch the vapours/ Make me a pillow out of toilet paper/ Concrete bench kickin’ off the haemorrhoids".

In the next track, ‘Ghetto Bird’ – a brilliantly atmospheric QDIII-produced cut that manages to aurally conflate the thunderous sound of the police helicopters Cube rails against

with eagles and pterodactyls – there’s a carjacking scene: "Officer Bird’s on his way and I don’t wanna see him/ Could you please give me the keys to the BM?/ See, I didn’t want to gank you, but don’t make me bank you…" And there’s a sound of a car door slamming before he finishes the line with a perfectly timed, "Thank you."

Of course, it wouldn’t be a Cube album without a couple of attempts at shock and awe – and, duly, the maestro of needle delivers. On a side two bristling with provocative barbs, ‘Enemy’ is a standout: Dutch producers Madness 4 Real gift Cube a rattling shuffle of a beat, still umbilically connected to (and recognisable as) the blues, over which he gets to clamber, slouch and declaim. It’s one of the album’s high points, where the track is rough enough to do justice to his overall plan of reminding anyone in doubt that he’s a hip hop purist at heart, but where the tempo and the syncopation allow him a great deal of space to construct intricate lyrical patterns, to really revel not just in the writerly wordplay but to savour the delivery as if the rhymes were edible, succulent. And of course he uses it to poke and goad and stir as only he truly knows how, with a lyric full of millennial tensions, evil portent and visions of a coming racial apocalypse that would make the ’92 rebellion/riots look like a

Sunday school picnic.

You want calculated, racially charged offence? He’s your man. At a point in history where the former Yugoslavia was descending into genocide, only Cube would have dared essay the couplet: "Send me a subpoena/ ‘Cos I’m killin’ more crackers than Bosnia Herzegovina" (and only he would have dared toy with the delivery, letting the beat kick a little comedic strut into the timing of the "punchline", so the name of the battle-born new country comes out as "Bosnia [pause] Herza, Govina"). Righteous fury and abstract Nation of Islam rhetoric, preferably with a little Dre/ George nod thrown in to season the pot? He’s got that covered, too: "Goin’ to the east, but straight from the westside/ Swing down sweet chariot, and let me ride/ Through the fire, through the fire – that will please us/ I know that Farrakhan is your baby Jesus". Homophobia and adjacent, similarly needless, provocation of Jews, rendered with a bouncing flow, the very

rhythm of the words insinuating that you have to take it as a joke, but a joke where your laughter makes you complicit in the bile that fuels it? Oh, you know he’s your man for that: "Three men in the tub, rub-a-dub-dub/ And it’s really scary now they’re in the military/ Sodom and Gomorrah – devil read your Torah."

And then, of course, there’s ‘Cave Bitch’ – a track right up there with whichever one of Cube’s wanton provocations you’d choose to exemplify the master of controversy at his most extreme and offensive. The track’s message is pretty clear: if you’re a white woman, you can by all means be an Ice Cube fan, but don’t, under any circumstances, think that he’d dream of having sex with you, because, genetically, you don’t have the kind of curves he’s interested in, and clearly, if you’re white and hanging around

with black guys, you’re not interested in them as human beings, you’re just indulging a racially motivated fantasy.

Does Cube mean any of it to be taken literally? He defended it at the time as an experiment – claiming that he wanted to see if the same people who ignored him calling black women "bitches" would get offended when he was clearly using the term to describe white women. But he extends what could have been handled adequately in four lines to the length of a whole song, and he took an awful lot of trouble to give it something approaching the consistency of an ideology.

The song’s intro is delivered by Khalid Abdul Muhammad, at the time an official spokesman for the Nation of Islam and right-hand man of its leader, Louis Farrakhan. It’s not clear whether this is a sample from one of Muhammad’s often rap-infused speeches, or a piece specially recorded for Cube’s record: either way, Muhammad sets the tone, rhyming about the "grafted, recessive, depressive, ironing-board backside… mutanoid, caucasoid, white cave bitch." Muhammad was no stranger to rap records: his is the voice speaking of how blacks brought to America as slaves were

"robbed of our name, robbed of our language – we lost our religion, our culture, our God" on Public Enemy’s ‘Night of the Living Bassheads’, and Cube had him introduce both sides of Death Certificate. But his views were as reliably divisive as his voice was recognisable – and, even if he was included here purely to reinforce the idea that Cube remained not just uncompromising but resolutely uncompromisable, the implication

has to be taken that Cube was endorsing an unapologetically racist agenda.

If it was simply all an attempt to cause calculated outrage, it couldn’t have worked any better: but, to be fair, Cube could not have known that his guest would create a controversy on the eve of release of the album which would overshadow any of the things the rapper was trying to say. On November 29, a little over a week before Lethal Injection‘s release, Muhammad gave a speech at a college in New Jersey where, answering a question from a member of the audience, he called for a novel solution to resolving racial tensions in newly post-apartheid in South Africa: "If we wanna be merciful at all, when we gain enough power from God almighty to take our freedom and independence from him [the white man], we give him 24 hours to get out of town by sundown. That’s all. If he won’t get out of town by sundown, we kill everything white that ain’t right that’s in sight in South Africa. We kill the women, we kill the children, we kill the babies. We kill the blind, we kill the cripples [impersonates someone with a mental handicap] – we kill them all. We kill

the faggots, we kill the lesbians – we kill them all. You say, ‘Why kill the babies in South Africa?’ Because they gonna grow up one day to oppress our babies – so we kill the babies. ‘Why kill the women? … Because they lay on their backs: they are the military’s or the army’s manufacturing centre. They lay on their back and the reinforcements roll out from between their legs. So we kill the women too."

The Anti-Defamation League took out a full-page ad in the New York Times, quoting liberally from the speech; an unrepentant Muhammad appeared on an edition of the Donahue chat show the following year, shortly after the House of Representatives voted by a majority of 327 to condemn his comments. He was stripped of his NoI role and eventually left the organisation.

It’s no surprise, then, that ‘Cave Bitch’ got rather trampled underfoot amid the stampede that Muhammad’s speech caused. Despite the election of Bill Clinton and the end of the Reagan/ Bush years, race in America remained a deeply polarised issue – check the audience question-and-answer session from the Donahue episode for an indication of quite how far the pendulum was then capable of swinging – and while Cube had played an important part in framing and energising the debate, rap was already losing its ability to shock. And, despite everything, the reaction to ‘Cave Bitch’ specifically, and Lethal Injection generally, was muted. Certainly, there were no calls for a boycott, no outraged editorials in music biz magazines, no sense that the artist was at the epicentre of a social or political convulsion, as had been the case with each of his three previous albums.

Partly this was a sign of the times having changed, but mostly, the failure of this album to upset quite as many people as before was testament to Cube’s considerable previous successes. With NWA he’d seemingly broken every taboo in the rock and pop handbook – more graphic violence than the average Hollywood action movie; enough animus against the police to spark questions from lawmakers; more swearing than is heard in a school playground in a week. Each of his solo albums had stuck the knife in and given it several vicious twists, and with each release, he upped his own ante. It’s not that ‘Cave Bitch’ isn’t shocking, or provocative, or offensive – it’s as obnoxious as anything else in his catalogue – but by the end of ’93, such deliberately controversial material had become an expected part of the landscape.

The record did well commercially – it remains his second-best-selling solo LP – but the days of a Cube album becoming a global talking-point had passed. That ability to become the focus of controversy rested not with the reactions of his fans, but his ability to project an aura of threat and menace to people outside rap, who didn’t understand it or where it came from, and who would take titles or phrases out of context and react to them in predictably censorious ways. And, from this vantage point 20 years on, it’s almost as if that sector of society had grown tired of being bated: as if they collectively thought, "Oh, that’s just Ice Cube – he always does that. If we ignore him he’ll go away."

And, lo and behold, that’s exactly what happened. It was five years before he made another album, by which time the era where a rap record could shock an entire society had passed. Whether one views it as the end of an era or the end of an error, Lethal Injection was the last of its kind.