When, in 1975, Harold Bronson of Phonograph Record magazine reviewed an album released in the previous year and wrote of its makers, “They could well be the future of soul music,” what 1974 LP would you imagine he was referring to? You might think of Standing On The Verge Of Getting It On, Fulfilingness’ First Finale, or Gil Scott-Heron’s Winter In America, to name just three enduring classics from that year. You probably wouldn’t consider the debut full-length from a British band that had already been around for six years, putting out an erratic run of singles that had scored wildly varying UK chart placings while being mostly ignored in every other territory: Hot Chocolate.

Yes, that Hot Chocolate. The band that a few months later would release their biggest hit, ‘You Sexy Thing’ and find themselves forever typecast as suburban plastic soul-pop kitsch, reliable purveyors of solid-gold wedding-disco anthems, and smoochy drivetime radio balladeers with just enough bump & grind to conjure up Babycham-fuelled bedroom kerfuffles in the sneering fantasies of youthful tastemakers straining to imagine the pallid perversions of middle-aged married life. Hot Chocolate, who, despite their 1978 international smash, ‘Every 1’s A Winner’ featuring one of the all-time great guitar riffs, and the fact that The Fall or early Human League could happily have covered its follow-up, ‘Mindless Boogie’, a one-chord, kraut-disco space-funk downer about the Jonestown Massacre, would never again be described by anyone as “the future of soul music” without the serious risk of Accidental Partridge.

Hot Chocolate would become one of the UK’s most commercially successful pop acts, famously enjoying at least one hit single every year from 1970 to 1984 and continuing to chart through the 90s, but they were never seen as credible. Singer Errol Brown’s songwriting talent was belatedly recognised with an Ivor Novello in 2004, and alternative acts from The Sisters Of Mercy (more on them later) to Tindersticks and Ty Segall have covered their songs, but always with some degree of ironic distance. The choice often seemed intended to demonstrate that the artist in question was so cool they could even cover Hot Chocolate and get away with it, rather than the actual truth: Hot Chocolate wrote great songs worthy of interpretation by a wide spectrum of different performers.

So, back in 1974, Hot Chocolate may not have been the future of soul music, but they certainly had a successful future ahead of them – though more reliably in the UK and Europe than the US. There, the very idea of an English band playing soul and funk was considered suspect, going against North American notions of the British as almost neurotically reserved and polite, regardless of ethnicity or skin colour. The fact that Cicero Park, their debut album, was taken seriously in the States, despite being a coals-to-Newcastle import from Blighty, says much about the ability of this hard-working, multi-racial London group to assimilate its influences and create something fresh, powerful and authentic of its own. (Average White Band’s single ‘Pick Up The Pieces’, released just weeks after Cicero Park, eventually went to the top of the Billboard charts in February 1975, but received wisdom today is that few who heard it realised this bunch of tightly drilled Scotsmen who could give the J.B.s a run for their money weren’t from the States.) Cicero Park failed to chart in the UK but secured a #55 placing on the Billboard 200. Perhaps, free from whatever associations and baggage Hot Chocolate had already acquired at home, critics in soul music’s birthplace simply recognised a quality LP when they heard it.

The beginnings of Hot Chocolate lie in the songwriting partnership between Brown, a Treasury clerk who had arrived from Jamaica with his mother at the age of ten, and Trinidadian bassist Tony Wilson, who in 1968 was living close to Brown in Hampstead. The pair hooked up with a loose group of London musicians to record a raggedly eccentric reggae cover of ‘Give Peace A Chance’. Brown’s lyrical additions required John Lennon’s approval, leading to the single being released on Apple, credited to “The Hot Chocolate Band” – a name coined by Apple press officer Mavis Smith.

That band broke up, but Brown and Wilson continued writing songs for the likes of fellow Apple artist Mary Hopkins and Herman’s Hermits, whose producer, Mickie Most, saw the potential of a reconfigured Hot Chocolate and made them the first new signing to his RAK label in 1970. Now featuring guitarist Harvey Hinsley, keyboard player Larry Ferguson, drummer Tony Connor and percussionist Patrick Olive, Hot Chocolate cracked the UK top 10 with the Cat Stevens-like ‘Love Is Life’ and followed it with the tough funk-rock of ‘You Could Have Been A Lady’, the missing link between ‘Sympathy For The Devil’ (Brown made no secret of his admiration for The Rolling Stones) and Primal Scream’s ‘Loaded’. More singles followed, switching styles from the Caribbean lilt of ‘I Believe (In Love)’ to the bubblegum boogie of ‘Mary Anne’ before the song that Brown would later see as their creative breakthrough, ‘Brother Louie’, hit #7 in April 1973.

Included on US pressings of Cicero Park but not in the UK, where it was still considered bad form to include previously released singles on an LP, ‘Brother Louie’ tackles racial prejudice head-on in its almost journalistic description of a doomed relationship between a white man and a black woman. Influential British blues musician and broadcaster Alexis Korner, then leading the Mickie Most-produced instrumental band CCS, delivers spoken-word sections that, over a bed of smouldering funk, matter-of-factly vocalise the hostility to the relationship from both parties’ families, emphasising the respective racial epithets that, while relatively mild, are still uncomfortable to hear today.

For Brown, the song was the first time he’d written about something that really mattered to him, and it marked the moment when Hot Chocolate got serious. As much as their first few years as a singles-only band were about finding their musical feet, their early instincts were purely geared towards short-term hits rather than a lasting career. With ‘Brother Louie’, Brown discovered that he could combine commercial success with artistic satisfaction, and it was at this point that he felt the band were ready to record an album.

It also helped that ‘Brother Louie’ was a massive surprise hit in America. The version that topped the Billboard Hot 100 however wasn’t by Hot Chocolate but by US soft rockers Stories, formed by singer Ian Lloyd and keyboard player Michael Brown. The latter was formerly of cult baroque pop band The Left Banke who, in a weird reverse mirror image of the ‘Brother Louie’ situation, had a 1966 top 10 hit in the US with ‘Walk Away Renee’, a song that only charted in the UK when The Four Tops remade it as a soul classic. Years later, ‘Brother Louie’ became the template for ‘Kinky Afro’ by Happy Mondays, whose Paul Ryder claimed he learnt the bass by endlessly playing along with Hot Chocolate’s Greatest Hits.

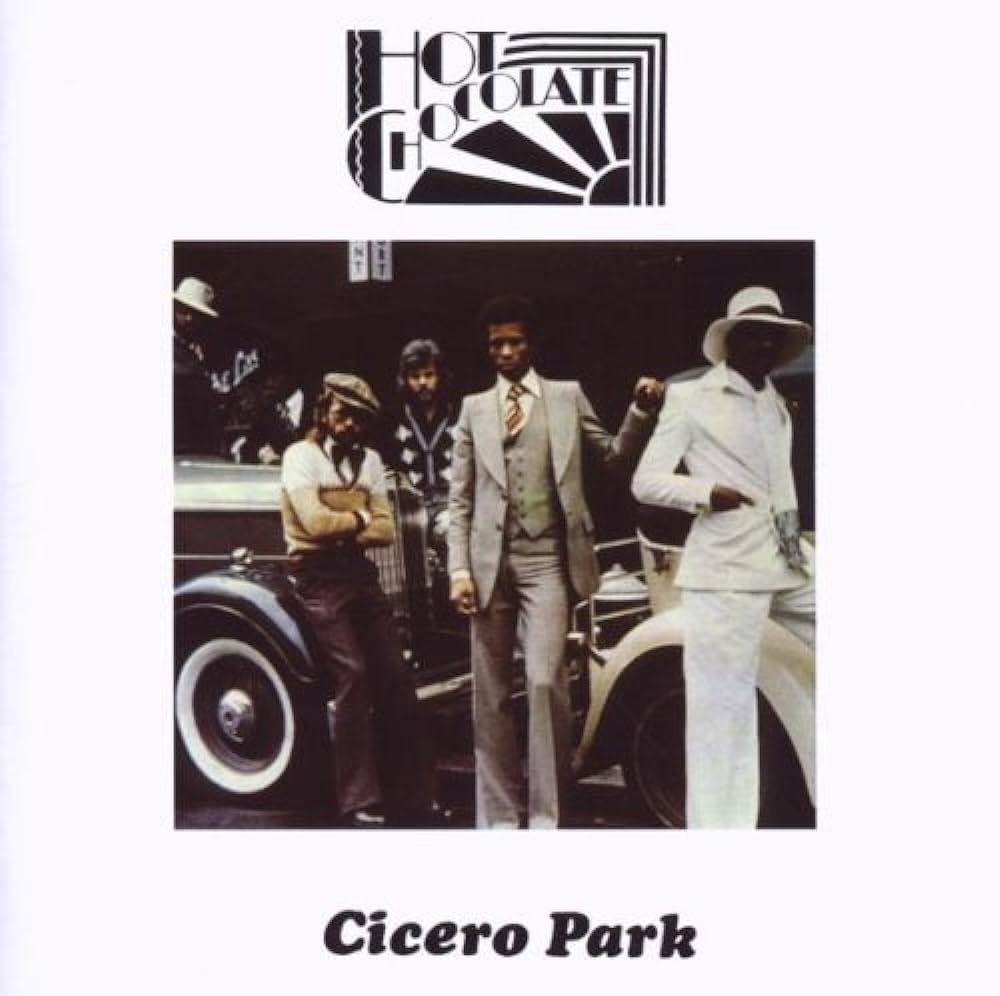

Stories’ ‘Brother Louie’, which substantially toned down the song’s lyrics, opened the door for Cicero Park’s US release on Big Tree Records, with nationwide distribution through Atlantic. It wasn’t just the hard-hitting delivery of the original ‘Brother Louie’ that raised eyebrows stateside: the album’s cover art, in which black bandleaders Brown and Wilson pose in sharp 30s-style suits in front of a vintage luxury car, while the white musicians appear to be dressed as chauffeurs or bellhops, was also deemed subversive.

As for the songs, every one’s a winner, from the moody, mournful Curtis Mayfield-Temptations funk of ‘Could Have Been Born in The Ghetto’ to Wilson Pickett via Sly Stone 60s R&B throwback ‘Funky Rock ‘N’ Roll’ which (like country-pop oddity ‘A Love Like Yours’ and orchestrated jam ‘You’re A Natural High’) features Tony Wilson’s softer, more sibilant lead vocals. But two songs in particular cast an inescapable shadow over the album, bookending the first side and setting a prevailing mood of dark, edgy despair that upbeat anthems like ‘Changing World’ and ‘Disco Queen’ can’t quite dispel: ‘Cicero Park’ itself, and ‘Emma’.

The opening title track pulls no punches, with doomy, Morricone-inspired spaghetti western rhythms and apocalyptic warnings of urban decay and environmental collapse. John Cameron’s arrangements are an essential ingredient throughout the album, but here his urgent, elegiac strings and flute combine with Brown’s tense growls of “life is dying out” and “don’t let it happen in your world” to make Cicero Park sound almost like a less opulent cousin to Bowie’s contemporaneous Diamond Dogs. It’s small change however compared to the lasting emotional impact of ‘Emma’.

A masterpiece of gothic soul, ‘Emma’ was famously covered by The Sisters Of Mercy and became a highlight of their mid-80s live sets. But even Andrew Eldritch couldn’t inject any more darkness and dread into the song than Hot Chocolate had already provided and had to fall back on po-faced camp instead. In 1984, ‘Emma’ was also the musical blueprint for New Order’s ‘Thieves Like Us’. Great as these takes are, none surpass the devastating power of the original.

Partly this is down to Errol Brown’s absolute sincerity. He was inspired to write the song by the death of his mother, and he delivers the lyric, telling of a lover’s suicide following a failed acting career, with chilling conviction. Mickie Most’s dry, claustrophobic production, with everything tightly gated, really comes into its own on this song, as do Harvey Hinsley’s brilliant, economical guitar parts, the simple ascending and descending fuzz riff capturing the feel of being trapped in an inexorable cycle of hope and despair. By the time Hinsley’s guitar starts screaming like Eddie Hazel’s on ‘Maggot Brain’ and Brown’s falsetto shrieks lead into the too-soon fade, it doesn’t seem extravagant to claim ‘Emma’ as the feminine, pop-soul counterpart to Suicide’s ‘Frankie Teardrop’, released three years later. One of the most harrowing songs ever recorded, ‘Frankie Teardrop’ similarly tells of a working-class suicide over a sparse, boxed-in backing, though with a far more violently masculine perspective. But unlike Frankie, Emma, we hope, has escaped her personal hell, and achieved a greater redemption than fame could ever have provided.

If Hot Chocolate never recorded anything else after ‘Emma’ they’d still be worthy of a place at pop’s all-time big table. That they became, if not the biggest stars the world had ever seen, then certainly household names of no little consequence, is a heartening vindication of their self-belief and talent. Cicero Park may be their most consistent album, but all the seven studio LPs that followed, up to and including 1983’s Love Shot, contain songs of quality, interest and even leftfield experimentation alongside more predictable fare. The point of this piece is not to wish they’d taken a different path after their debut, nor to be snobbish about the songs that gained them huge mainstream success, or the people that love those tracks. It’s to celebrate a band that were always stranger, more adventurous and more outspoken than they’re generally given credit for and to hope that, in a changing world, Cicero Park will eventually get the love it deserves.