Chance is indeed a fine thing.

And it was pure chance that I tuned in to John Peel’s show late one night in the opening overs of 1984 to be immediately captured by the record that came through the headphones. First it was the drone, rising with all the majesty of a phoenix from the ashes, before giving way to a crashing G chord that descended to a strummed E minor. And then the acoustic guitars, twanging licks, a tale of heartbreak and yearning with a chorus that made me want to punch the air. Part country, part power pop and wholly rock & roll, the effect was utterly seductive. I didn’t want it to end, but I had to know who the hell this was.

"That was the Hoodoo Gurus from Australia," intoned Peel in his trademark monotone before adding, "And it’s out now on the Demon label."

The single was located in Revolution Records in Windsor, a compact and bijou emporium specialising in the latest releases, obscure vinyl, part-exchanges and gig tickets. The cover was plain enough; no picture, just a black sleeve with a red label exposed through the hole on the front. Rushing home, I played the single and its B-side – a slab of glam ramalama called ‘Be My Guru’ – over and over again, with the full expectation that, like much of the stuff that Peel aired, Hoodoo Gurus would never be heard of again.

So it was with unrestrained joy that I discovered that Hoodoo Gurus’ debut album Stoneage Romeos, released in March 1984, had made it to these shores. I can still recall the nod of approval from Revolution Records’ owner, a hirsute and stocky individual who’d seemingly been bypassed by the punk wars and bore more than a passing resemblance to Oddbod, the strange creature that acted as Kenneth Williams’ henchman in Carry On Screaming!.

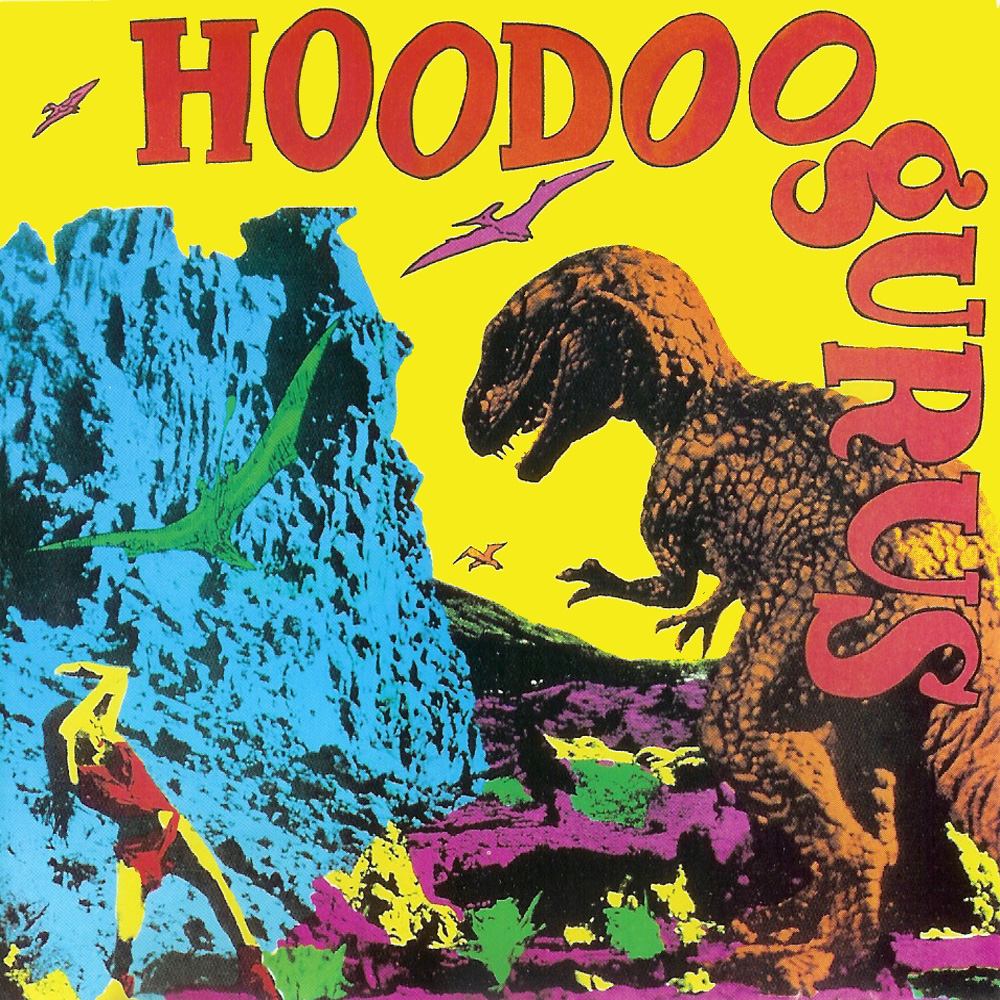

Even before putting the album on, its cover was alluring and a statement all in itself. A homage of sorts to Hammer’s ridiculously camp caveman b-movie One Million Years BC, it hinted towards the elemental joys contained within: day-glo colours, menacing Tyrannosaurus rex, cowering cavewoman, and a band logo that looked as if it had been drawn on the back of an exercise book during a particularly dull double maths session on a rainy Tuesday afternoon.

The back cover, similarly, contained equally lurid colours and a DIY aesthetic courtesy of designer Yanni Stumbles. The individual pictures of the band members resemble re-touched newspaper cut-outs, and their images tease as to what’s contained within: drummer James Baker resembles doomed Rolling Stones founder Brian Jones; singer-guitarist Dave Faulkner sports drainpipes and Chelsea boots; bassist Clyde Bramley is draped in a western shirt, while lead guitarist Brad Shepherd, all spiked mullet and eyeliner, suggests the unholy lovechild of Siouxsie Sioux and Keith Richards.

Much like the best rock and roll of the early 80s, Stoneage Romeos’ opening salvo of ‘Let’s All Turn On’ was both educational and supremely entertaining. The Cramps had set the bar with the release of Songs The Lord Taught Us (1980) and Psychedelic Jungle (1981) as well as a handful of singles that were eventually collected in the Off The Bone (1983) compilation. Fusing the unrestrained power of first generation 50s rock and roll with psychedelia and garage rock, and knowing sexual innuendo with schlock-horror imagery, The Cramps highlighted the missing link between rock’s initial big bang and the punk explosion of the late 70s – those little known and obscure nuggets from the then much-maligned and still argued over decade, the 1960s. The Year Zero orthodoxy of punk would have it that nothing of worth – with the obvious exception of The Velvet Underground and The Stooges – had been recorded prior to 1976 (at least not by white rock bands), yet The Cramps’ choices of obscure covers did much to make a generation realise that punk was nothing particularly new, and that the prevailing 60s image of dope-smoking, bellbottom-wearing hippies was just a small part of a much wider picture.

Those early albums by The Cramps were schools for scoundrels, with extra-curricular activity encouraged through seeking out original versions of say, The Novas’ ‘The Crusher’ or The Bostweed’s ‘Faster Pussycat’ (the latter of which alerted my teen self to Russ Meyer’s film). And here, in a similar vein, were Hoodoo Gurus, who managed to pack all this information into one song. Ushered in by a restless bassline and slashing guitars, ‘Let’s All Turn On”s lyrics list a series of influences, further reference points to be sought out: "Shake Some Action, Psychotic Reaction/ No Satisfaction, Sky Pilot, Sky Saxon/ That’s what I like, that’s what I like…"

I can still recall trying to take it all in. Okay, so I knew ‘Psychotic Reaction’ and ‘(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction’ (who didn’t?) but ‘Shake Some Action’? ‘Sky Pilot’? Sky Saxon? What the hell were these? And so it went on: "Waiting for my man, baby/ Can the Can/ I Want To Hold Your Hand, remember Sam The Sham?/That’s what I like, that’s what I like…" Among the exhilarating lead breaks and backing vocals, a link was being formed from the music that I did know to a whole wide world I wasn’t yet aware of: The Flamin’ Groovies, The Seeds and so on. This wasn’t just a song but a manifesto, a call to arms that would prove irresistible, and one that sets the tone for the rest of the album.

Having a manifesto is one thing but capturing the spirit of those trailblazers and delivering on it is quite another. Because that’s what rock & roll at its best is supposed to be about: capturing that burst of uncontrolled teenage homones, exuberance, shooting first and not asking questions later, and flipping the bird to the crushing dullness of the 9-to-5 world and the inevitability of death and taxes. And this is precisely what Stoneage Romeos is all about. Drilling deep into this rich well of musical inspiration and that unabashed sense of teen hedonism, Hoodoo Gurus’ debut spurts out eleven killer gems like oil gushing from a drill in the desert. Devoid of cynicism or ironic smirking, this is a spunky collection of songs with a cheeky glint in their eye and a knowing grin on their face. That it happens to be, on more than one occasion, laugh out loud funny, is simply icing on an already highly delicious piece of confection.

Even the album’s pre-occupation with death – ‘Dig It Up’, ‘Death Ship’ and ‘Leilani’, for example – is approached with a comic book mentality meant to amuse rather than offend. Over a sleazy riff and grinding chords, the protagonist of ‘Dig It Up’ finds himself mourning at his girlfriend’s grave ("My girlfriend lives in the ground / My friends ask why she’s not around…") before considering a somewhat grim compromise ("You can’t bury love / You gotta dig it up"). Elsewhere, ‘Leilani’ – a version of which was originally released a single in late 1982 – looks back to the RKO movies of the 30s and 40s, as a native chief’s daughter is sacrificed to the appease the gods while her boyfriend looks helplessly on. Of course, all of this would be as daft as a brush were it not for the power of the music. ‘Leilani’ is motored on by stackheeled, glam-stomping beats, a droning hammered-on chord and guitars that resemble a barrage of baritone saxophones, all driving the narrative forward with such bloody-minded conviction that any notions of puerility are easily swept aside.

This is why closer ‘I Was A Kamikaze Pilot’ is such a glorious triumph ("I was a was a kamikaze pilot/ They gave me a plane/ I couldn’t fly it/ Taught how to take off/ I don’t know how to land…") – it’s played straight and with a passion that belies its comic sensibilities. Single coil guitars are fed into toasty valve amps to create bright rhythms, bent strings and monstrously righteous noise that’s aimed straight at the hips. This track in particular is a heady and potent combination, and one that still holds up now. But there are moments of tenderness, too. ‘My Girl’ is a paean to teenage heartache, with Brad Shepherd’s twanging solo suggesting Duane Eddy had he been raised in the outback, while ‘I Want You Back’ benefits from an extra verse that was absent from the single version.

A contributing factor to the longevity and timeless feel of Stoneage Romeos is Alan Thorne’s sympathetic production. Unlike so many bands blighted by 1980s production values, here James Baker’s drums sound like drums. The snare cuts through on its own terms, each beat a whiplash to drive feet to the dancefloor while the guitars fizz, riff and slash with warmth and fullness that, at the time, was in all too short supply. Call it an alignment of the stars, call it alchemy, call it what you will, but the elements drawn together on Stoneage Romeos still resonate now. Indeed, since its release, not a year has gone by that the album hasn’t found itself on the turntable round these parts; less due to nostalgia, more for the fact that it contains within itself a bottled essence of rock & roll, a powerful musical genie to be released on demand. The primal and elemental fun packed into Stoneage Romeos’ grooves remains an essential tonic for the pressures of an uncaring world. If you’re still unaware of this record’s charms, then consider yourself urged to take the plunge now. You won’t regret it.