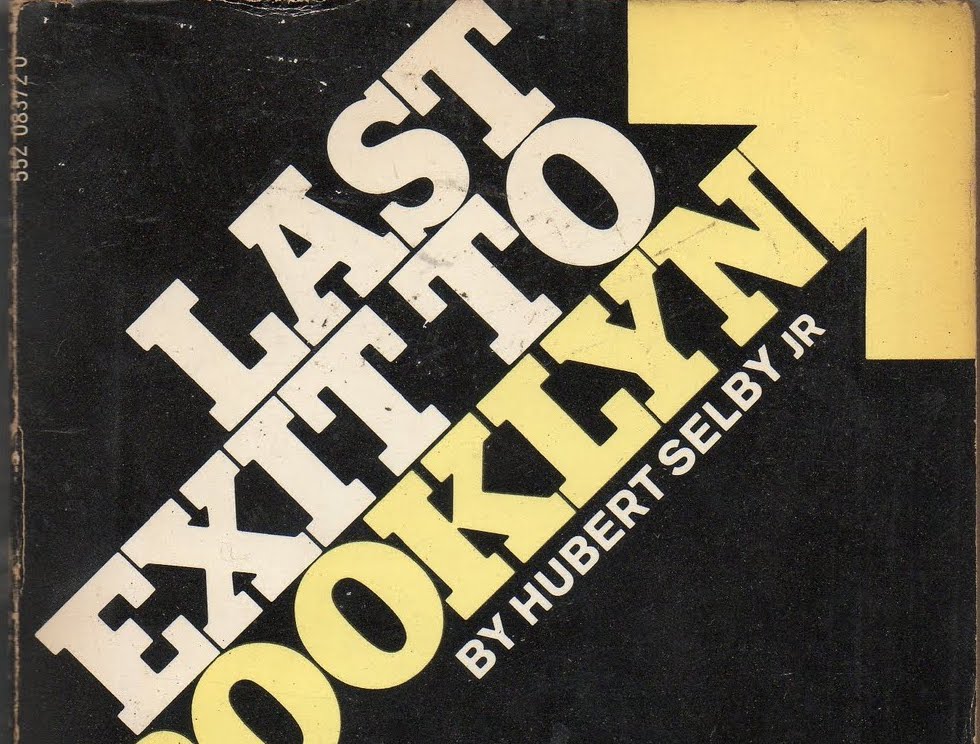

This year sees the 60th anniversary of Hubert Selby Jr’s controversial debut novel, Last Exit To Brooklyn. With its frank depictions of then-taboo subjects such as gay sex, recreational drug use and domestic and sexual violence, it is unsurprising that the book caused something of a sensation upon its release. Less a novel in conventional terms of possessing a central narrative/protagonist, Last Exit To Brooklyn is rather a collection of short stories set in the working-class district of Suset Park – depicted here as an infernal demimonde of hopped-up hoodlums, cold hearted sex workers and, to adopt the parlance of the novel, lonely drag queens. It is the book Allan Ginsberg proclaimed “should explode like a rusty hellish bombshell over America and still be eagerly read in a hundred years.” It is also Selby’s masterpiece.

The novel began life in 1957 with the publication of a short story that would eventually become the second chapter of the novel. At approximately 50 pages in length, ‘The Queen Is Dead’ tells the story of Georgette, a trans sex worker who, along with her “drag queen” friends, decide to host a party for a gang of neighbourhood roughs. Georgette is hopelessly in love with the gang’s leader, Vinnie, who enjoys Georgette’s attention but is simply using her for sexual kicks and to gain access to her ready supply of drugs (chiefly “bennies” or Benzedrine: a powerful, and that time still legal, amphetamine). As the party becomes more and more strung out – with Georgette shooting up heroin in the bathroom – the romantically decadent atmosphere degenerates into a kind of violent orgy. The story climaxes with Georgette undergoing a humiliating sexual encounter with Vinnie, before fleeing the apartment and then ODing. And though her ultimate fate is ambiguous, she certainly suffers a physic death if not a physical one.

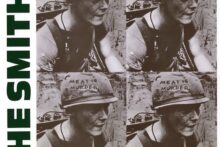

In its compassionate yet unsentimental depiction of the doomed Georgette, ‘The Queen Is Dead’ is perhaps Selby’s greatest achievement. And it can lay claim to have influenced three pieces of music that, to paraphrase Allen Ginsberg, will undoubtedly still be eagerly listened to in a hundred years’ time. And while its influence on two of the works is largely unequivocal, its influence on the third is more contentious and will require some unpacking. So, let’s begin with the most obviously unequivocal work – the one that wears its influence on its (record) sleeve: the Smiths’ 1986 album, and its title track, The Queen Is Dead.

“I’m the 18th pale descendent / Of some old queen or other” The Smiths – ‘The Queen is Dead’

Like all the best allusions, The Queen Is Dead works as a stand-alone title without any prior knowledge of the original source. And while it may seem that the homosexual connotations of “queen” do not extend much further than the cover artwork (Alain Delon’s androgynous beauty gazing glassy-eyed from out of the final scenes of 1964 French noir, L’Insoumis) traces of Selby’s lovelorn protagonist linger on in the title track’s playful advocation for regicide – like a watermark in old pound note.

To begin, there’s the sample that opens both the album and the song: a snatch of ‘Take Me Back To Dear Old Blighty’ from Brian Forbes’ 1962 British film, The L-Shaped Room. The scene in question is another drunken party: this one held in a seedy Notting Hill boarding house rather than a New York apartment block. And though this party is fuelled by cheap booze instead of hard drugs, the guests are similarly made up of individuals scraping by on the fringes of “respectable” society: as well as the unmarried pregnant protagonist, there are a couple of sex workers, a gay Black jazz musician, and, most strikingly, Cicely Courtneidge as an elderly lesbian and ex-music hall star. It is Courtneidge who leads the World War I sing-a-long, and she does so in male drag – changing into her old army uniform and affecting a gruff male voice – an image harking back to the previous scene when she bemoans how modern pantos aren’t “much cop nowadays … fancy a man playing the Principle Boy! That’s a disgrace to the profession”.

And then there’s the title track proper, ‘The Queen Is Dead’, which also seems to contain sly allusions to Selby’s chapter. Where Selby gives us an apartment of drag queens, Morrissey gives us (the then) Prince Charles “dressed in [his] mother’s bridal veil”. Where Selby presented us with a gang of neighbourhood roughs, Morrissey describes a “nine-year-old tough / who peddled drugs”. Even the throwaway Freudian couplet – “But when you’re tied to your mother’s apron / No-one talks about castration” – could be a humorous nod towards a disturbing scene at the beginning of Selby’s story, when Georgette is stabbed in the leg – “I’ll makeya a real woman without goin ta Denmark… You don’t want that big sazeech getting in yaway Georgie boy. Let me cut it off…” – and then taken back home to her mother to recuperate: “She rocked with Georgette’s head cradled in her arms.” And then there’s the closing refrain – “life is very long when you’re lonely” – which, in the context of the song, seems something of a non-sequitur; but, if considered in the wider context of the song’s allusions, could be taking us back not only to Courtneidge’s lonely lesbian and a long-gone “dear old Blighty”, but also to Selby’s heartbroken drag queen. Indeed, The Smiths’ ‘The Queen Is Dead’ is where Morrissey’s twin obsessions with the decadent glamour of the gay, mid-century New York City/New York Dolls (who he once memorably described as “transexual junkies”) and the monochromatic realism of British kitchen sink drama come together to create a fascinating hybrid: a witty Ortonesque state-of-the-nation address and one of the Smiths’ most powerful and provocative moments. And, in a pleasing piece of synchronicity, Johnny Marr has credited the inspiration for his furiously driving rhythm guitar part to the Velvet Underground’s ‘I Can’t Stand It’ (which had been released the previous year on the outtakes collection, VU) – bringing us nicely to the second major work of music to have been influenced by Selby’s 50-page chapter.

“Do it just like Sister Ray said” The Velvet Underground – ‘Sister Ray’

If the Smiths took Selby’s chapter and playfully repositioned it to evoke a plurality of subtle allusions, The Velvet Underground simply lifted the more outré elements of the plot, added a few more outré elements of their own, put their heads down, turned their amps up, and created a thrilling, seventeen-and-a-half-minute proto-punk monster. The closing track of 1968’s White Light/White Heat album, ‘Sister Ray’ does not merely allude to Selby’s drug-fuelled party, the song is practically its aural equivalent: an all-out sonic attack on our senses and sensibilities. This is a debt Lou Reed has happily acknowledged, describing ‘Sister Ray’ as “Selby uptown” and the plot of the song as “a bunch of drag queens taking some sailors home with them, shooting up on smack and having this orgy, when the police appear.” Over a relentlessly primordial three-chord chug, dingdongs are sucked, sailors are shot, carpets stained and mainlines searched for. ‘Sister Ray’ is all attack, all surface, Hubert Selby’s nuanced “drag queen”, Georgette, brutally usurped by the tyrannical Sister Ray. (Though one of the chapter’s most moving moments – Georgette’s recitation of Poe’s ‘The Raven’ – is subtly alluded to in Reed’s “Now who’s that knocking / Knocking on my chamber door?”)

As well as Selby’s text, Reed has cited a real-life model for Sister Ray: a “black queen” he and John Cale had once run into uptown (“very nice, but flaming”). Similarly, when Reed interviewed Selby in 1989, the writer divulged that Georgette was the only character in Last Exit To Brooklyn “that approaches being real… There was a young gay kid named Georgie. Georgette. So, that part is accurate. The way Georgie is in the book is me. I mean, you know, my imagination … whatever.”

Which is a far more open reply than the various deflections and obfuscations Van Morrison has trotted out over the years whenever quizzed on the model for one of his greatest creations – and the third piece of music that I’d like to suggest was influenced by Selby’s most infamous chapter.

“In the corner playing dominoes in drag, / The one and only Madame George” Van Morrison, ‘Madame George’

Given that ‘Sister Ray’ and ‘Madame George’ were both released in 1968, possess eponymous, similarly constructed titles (female honorific / male Christian name) and share a drug-fuelled-party-setting (with the threat of a police raid hanging over both) it is tempting to imagine that one of the songs must have influenced the other – especially when you consider that between 1967 and 1968 Morrison and the Velvets were both knocking around New York and Boston, playing the same live circuit. However, composition and recording dates do not quite match up. On March 28 and 29, 1967, Van Morrison was in New York recording his first solo single (‘Brown Eyed Girl’) for Bert Berns’ Bang label. Mere days later, after Morrison had returned to Belfast, the Velvets debuted ‘Sister Ray’ at The Gymnasium on 71st Street. Then, when Morrison returned to NYC later that summer to make more recordings for Bang, the Velvets were already sequestered in a studio recording White Light/White Heat. And although the first version of ‘Madame George’ wasn’t recorded until November of that year (with the more famous Astral Weeks version recorded ten months later in September 1968) by all accounts Morrison wrote ‘Madame George’ during his Belfast sojourn.

So, are these similarities between ‘Madame George’ and ‘Sister Ray’ mere coincidence? Or could it be that they both share some of Georgette’s DNA? Naturally, one Georgette does not a Madame George make. But to read ‘The Queen Is Dead’ with ‘Madame George’ in mind does throw up some quite remarkable similarities. What’s more, in turns of phrase and imagery, in its sublime pathos and empathy, ‘Madame George’ cleaves far closer to Selby’s chapter than it does to ‘Sister Ray’.

For example, compare this extract from Selby’s ‘The Queen Is Dead’ to 1967’s earlier, more sexually explicit, version of ‘Madame George’ (which replicates a party-like atmosphere from the off with lively in-studio chatter and Morrison’s barked instructions to “Put yer fur boots on!”):

“[H]e turned, still laughing, and went to the bathroom (his eyes still bugging out of his head. O Christ he is high. It will be beautiful!!!) and roared as Camille leaped from the bathroom when he goosed her, dropping her brushes then carefully stooping, watching the bathroom door, picking them up and dashing to the living room.”

‘The Queen Is Dead’

“And then your self-control lets go / And suddenly you’re up against the bathroom door / The hallway lights are finally getting dim / You’re in the front room touching him”

‘Madame George’ 1967 version

Again, this could be mere coincidence. But for a 50-page chapter there do seem to be an awful lot of similarities between the two texts. Compare:

“She asked him to come over with some of the boys…”

‘The Queen Is Dead’

“And all the little boys come around”

‘Madame George’

And:

“Lee clicked into the room wearing a pair of Sheilas stockings and best shoes…”

‘The Queen Is Dead’

“The clicking clacking of the high-heeled shoes”

‘Madame George’

And:

“Tony asked if she should call the police so they could take her to a hospital. You ain’t calling no cops…”

‘The Queen Is Dead’

“Then from outside the frosty window raps / She jumps up and says “Lord, have mercy I think that it’s the cops”

‘Madame George’

And:

“Si, A candle. Soft candle light … and I will read to you. And we will drink wine. No. Its not cold. Not really. Just the breeze from the Lake. Its so lovely. Peaceful.”

‘The Queen Is Dead’

“And that smell of sweet perfume comes drifting through / In the cool night breeze like Shalimar”

‘Madame George’ 1967 version

Throughout Selby’s chapter there is the recurring motif of a ballerina, either evoked derogatively to mock Georgette’s effeminacy:

“[She] screamed and jumped up, holding her injured leg with both hands and hopping up and down on the other. They whistled, clapped their hands and someone started singing, Dance Ballerina Dance.”

Or else the image of the dancer is recalled by Georgette as a feminine ideal:

“Hundreds of cellos [will play] and we will glide in the moonlight, pirouetting to THE SWAN.”

That the next song on Astral Weeks is ‘Ballerina’ could just be yet another coincidence. But the fact that Morrison once described this song as being “possibly about a hooker” does appear to place it firmly in Selby’s milieu. (Interestingly, ballet and cross-dressing also crop up on Side 2 of the Smiths’ The Queen Is Dead LP in the form of ‘Vicar In A Tutu’.)

The image of the swan reappears in the closing passages of the chapter, as Georgette ODs:

“A swan… See, she glides to us. Us. For us. O how white…”

The final track on Astral Weeks, ‘Slim Slow Slider’, employs similar imagery, and concerns death by heroin intoxication:

“Horse you ride is white as snow…”

Needless to say, this is purely speculative. But it’s worth bearing in mind that although Last Exit To Brookyln was published in America in 1964, it wasn’t published in the UK until January 1966, where its controversial contents saw it become both a best seller and the subject of a much-publicised obscenity trial. Given that Morrison was an avowed fan of American music and literature (his 1982 single, ‘Cleaning Windows’, lists his adolescent reading habits as “Kerouac’s Dharma bums and On The Road”) the demotic Beat-like prose of Last Exit To Brookyln is almost certainly a book that would have appealed to his tastes. Especially when one considers that a couple of months after the UK publication, Van Morrison and Them flew to JFK to embark upon their first US tour, where the book would have been readily available. (And could this explain the recurring queer themes in his songwriting around this time? During the same recording session as ‘Madame George’, Morrison also recorded ‘The Back Room’, which could be a reference to the back room of the gay bar frequented by the protagonist of the ‘Strike’ chapter of Last Exit to Brooklyn. The Bang sessions also produced ‘Joe Harper Saturday Morning’ which features an “old queen”; and then there’s ‘He Ain’t Give You None’ with “old John / Flog[ing] his daily meat.”)

Two of the most illuminating pieces of writing on Astral Weeks are by Lester Bangs and Greil Marcus, both of whom seem to come tantalisingly close to making a connection between ‘Madame George’ and Selby’s ‘The Queen Is Dead’. In Lester Bangs’ 1978 essay on Astral Weeks (commissioned, funnily enough, by Greil Marcus) he describes Madame George as “a lovelorn drag queen” and her companions as being “only too happy to come around as long as there’s music, party times, free drinks and smokes, and only too gleefully spit on George’s affections when all the other stuff runs out…”

While in 2010’s, Listening To Van Morrison, Greil Marcus has this to say about Madame George: “In George’s apartment, with the frayed damask cushions and the heavy drapes making the air close, the boys watch as George changes the LPs and 78s on the box, handling each so carefully, thumbs never touching the grooves, strange records by Billie Holiday and Charlie Parker that speak a different language.”

Both Bangs’ and Marcus’ descriptions read more like vignettes from ‘The Queen Is Dead’ than ‘Madame George’. And what’s more, there is no mention of Charlie Parker in ‘Madame George’ but Georgette actually does listen to Parker in ‘The Queen Is Dead’. The music’s effect on her is couched in similarly other-worldly terms:

“…and the strange rhythms of the Bird ripped to her, the piling patterns of sound all falling properly and articulately into place, and there was no wonderment at the Bird blowing love.”

Given Marcus’ propensity for making unlikely leaps of fancy in order to illuminate connections between texts, it is curious he declines to make such a leap here.

Even stranger still, Lou Reed also appears to skirt tantalisingly close to making a connection during a 1985 interview with writer Joe Smith. Smith brings up the topic of Van Morrison, prompting Reed to cite Astral Weeks as one of his favourite albums (“top ten”) and the following rhapsodic response:

“I like Van Morrison a lot… His voice is just incredible. One song he did, ‘Madame George’, lyrically struck me on the same thing I’m talking about [literate lyrics dealing with adult concerns] like I got intrigued that way…”

Frustratingly, Reed is not asked to elaborate, and the interview soon ends. (Meanwhile, in another case of pleasing synchronicity, the Velvet’s no.1 fan, David Bowie, not only included Last Exit To Brooklyn in his list of the 100 Books that changed his life – claiming he had “formed a desperate identification” with it – but in 1969 was covering ‘Madame George’ alongside ‘White Light/White Heat’ and ‘Waiting For The Man’. Again, no connection was made.

Of course, it’d be reductive to suggest that the character of Madame George is based solely on Georgette. Any influences have long since transcended their origins, having been refracted through Morrison’s poetic sensibility and memories of his Belfast childhood. But Georgette can surely be added to the list of candidates cited over the years as models for Madame George – such as Van Morrison’s Aunt Joy and W.B. Yeats’ wife, “George” Hyde-Lees. Indeed, Morrison himself has previously claimed (perhaps a little disingenuously) that ‘Madame George’ has got nothing whatsoever to do with a trans woman and is about “six or seven different people who probably couldn’t find themselves in there if they tried.” He has also claimed (perhaps a little revealingly) that ‘Madame George’ is “totally fictional. These are short stories, in musical form – put together of composites, of conversations I heard, things I saw and movies, newspapers, books, and comes out as stories.” (My italics). Of course, at one point he also claimed that ‘Madame George’ is about “a Swizz cheese sandwich” but we’ll leave that to one side.

Maybe we should end with Lester Bangs, who writes that Astral Weeks is about people “stunned by life” and reminds us that ‘Madame George’ is “not about a drag queen”, but is actually “about a person, like all the best songs, all the greatest literature.” He could be talking about Hubert Selby’s tragic heroine, Georgette, and the bruised and bruising masterpiece that is Selby’s Last Exit To Brooklyn.