The ‘progressive’ tag is a divisive and often misleading one to anyone unaware of the many variable forms of musical expression labelled as such may take. Although the term has gained (and occasionally lost again) a number of unfortunate associations over time, in itself it merely implies a form of music with aspirations beyond the limiting structures usually associated with rock, folk or pop. It is a form of critical laziness to suggest any kind of uniformity of stylistic output across bands that have been labelled progressive, just as it is a form of ideological tyranny to insist that musical invention can only legitimately exist if expressed within certain, immutable configurations.

Punk may have provided the necessary impetus to altering the musical status quo of the late 70s but it’s generally accepted that the more eclectic post punk template which followed in its wake produced the more interesting musical innovations. Public Image Ltd, who had such diverse influences as Can and Van der Graaf Generator, were always a more intriguing proposition than the Sex Pistols as far as I’m concerned. Bands such as King Crimson had little in common with the likes of Yes, or Emerson Lake and Palmer. Henry Cow, perhaps the most progressive of all English bands, were influenced by early Frank Zappa, as well such figures as Bela Bartok, Edgard Varese, John Cage and Sun Ra, and were about as far removed from the mainstream 70s prog bands as it was possible to be. Although their uncompromising music and defiantly anti-commercial stance meant they brought little financial success to Richard Branson’s Virgin label, which eventually dropped them when it began focusing on more commercial acts in 1977, Henry Cow spawned a genre all their own (Rock In Opposition or RIO) and produced an almost bewildering number of excellent spin-off projects and associated bands that influenced many subsequent generations of musicians.

When I first met Cardiacs’ Tim Smith after a gig at the Crazy House in Liverpool in 1998, they were the first of many names he gave me when I inquired of his musical influences. I was in the middle of an intense Krautrock phase at the time but it was evident from talking to Tim that he was more interested in composed than improvised music. I had heard the name Henry Cow but not their music. I was aware of the Soft Machine at the time and Bartok’s wonderful Concerto For Orchestra was already a favourite, so they made total sense to me when I picked up their first album after his recommendation.

Henry Cow were formed in 1968, whilst its core members Fred Frith and Tim Hodgkinson were attending Cambridge University. Violinist and guitarist Frith, who was studying English Literature, met Hodgkinson, a social anthropology student, in a blues club at the University and proceeded to bond during a spontaneously improvised hour of violin and alto saxophone that Frith later recalled as "a ghastly screaming noise". Hodgkinson introduced Frith to a range of new music, most notably the work of Charles Mingus and Ornette Coleman. Soon the pair were performing their "dadaist blues" regularly together and played their first gig as Henry Cow supporting Syd Barrett’s incarnation of Pink Floyd at the Architect’s Ball in Cambridge on 12 June 1968.

Although the popular apocryphal reasoning behind the band’s unusual moniker was that it was derived from a shortening of the name of the American composer and theorist, Henry Cowell, the band themselves have always denied this was the case and Hodgkinson claimed instead that it was merely "in the air" and without connection to anything else. After that, the band underwent a number of personnel changes that exposed them to different influences along the way. Early bass player Andy Powell was studying music at King’s College under the British-Australian composer Roger Smalley, who is said to have provided the spark of inspiration behind the idea of writing lengthy and complex musical scores intended to be played within the context of a rock group.

Bassist John Greaves joined the band in 1969, and with Hodgkinson doubling on organ as well as reeds, the band played Glastonbury Festival, which also featured Gong on the bill, in June 1971. A number of drummers came and went during these early years and it was not until Chris Cutler joined in September 1971, that the group finally settled into its long-term incarnation of Frith, Hodgkinson, Cutler and Greaves. The band moved to London and recorded their first session for John Peel in 1972 after entering the Radio 1 DJ’s ‘Rockortunity Knocks’ competition the previous year. During the years that followed, the band worked on projects for theatre (including Euripides’ The Bacchae and Shakespeare’s The Tempest), played support for acts as diverse as Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac, the Velvet Underground, Faust and later Captain Beefheart, and recorded five studio albums and one live double.

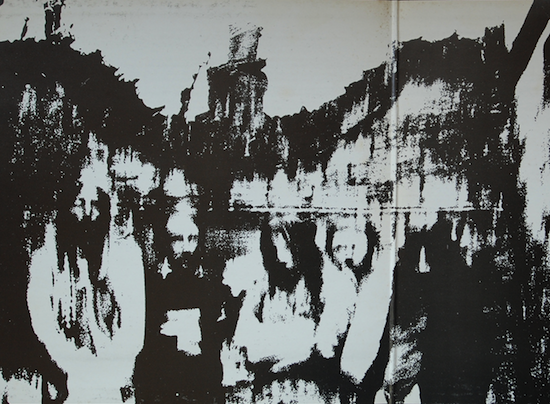

The band’s first album Leg End, a reference to its cover featuring the first of three sock paintings by artist Ray Smith, was more noticeably influenced by the Canterbury jazz-rock scene than the recordings that followed and is undoubtedly the best place for curious beginners to start. The album has a number of high-points, including the wonderfully titled ‘Nirvana For Mice’ whose scampering time signature conjures up the patter of thousands of tiny rodent feet, the beautifully expansive ‘Amygdala,’ and the uplifting and epic ‘Teenbeat’. The only non-instrumental track, ‘Nine Funerals Of The Citizen King,’ to which the whole band contributes vocals, is the first explicit example of the band’s political stance: "If we live (we live) to tread on dead kings/Or else we’ll work to live to buy the things we multiply/Until they fill the ordered universe."

Chris Cutler once amusingly said (although one wonders how much humour was intended): "Others experimented with drugs; we did it with radical politics." Their abstract avant-garde approach to music, allied with their own extreme take on left-wing politics led to disagreements with some individuals who also posited themselves within that part of the political spectrum, most notably the composer Cornelius Cardew. Henry Cow themselves refused to accept that reaching the working class meant having to revert to the simplest of musical forms. Which is not to say that they were dismissive of other forms of music, or as elitist as some descriptions of their own music might sometimes make them sound. Fred Frith has always been forthright about the influence that blues musicians like Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters had on his guitar playing when he first heard them as a young man. He has also acknowledged the debt his music owes to Eastern European folk music. As he stated in a 2012 interview for Psychedelic Baby blog – the first time he heard any musician other than Dave Brubeck playing in "something other than 4/4" was when a Yugoslavian schoolfriend played him some traditional Balkan folk music.

Henry Cow’s music, whilst not for everyone, is certainly unique, although I wouldn’t describe it as elitist in any sense. An amalgamation a wide range of influences, it was borne more of an aesthetic decision to discover their own path, away from any existing genre or any kind of mainstream and eventually into some kind of pagan sounding, abstract wilderness that few (perhaps none) had walked before. Already unique in comparison to other bands of the era, by the time of 1975’s In Praise Of Learning and 1979’s Western Culture, they truly sounded like no one else.

‘The Decay Of Cities’ from the latter, utilising Derek Bailey style guitar and a terrifying, almost industrial sounding passage, indeed sounds like its title suggests. In practical terms, the band’s politics manifested itself in traveling and often living communally, with very little in the way of available finances. Of necessity, putting on alternative shows for themselves and other bands who similarly existed on the fringes. The first Rock In Opposition festival took place on March 12, 1978, when Henry Cow invited Stormy Six (from Italy), Samla Mammas Manna (from Sweden), Univers Zero (from Belgium) and Etron Fou Leloublan (from France), to play at the New London Theatre. The aims of the movement were defined threefold; as the pursuit of musical excellence, a desire to work outside the confines of the music business and with a commitment to the social aspect of performing rock music. Although, as in any musical movement, far more diversity of idea existed amongst participating groups than was implied by the umbrella term, certain themes and influences can definitely be discerned amongst them. The influence of Zappa, Bartok, modern takes on chamber music and the many forms of Eastern European folk music are recurrent threads that run through all of those group’s music.

The term RIO has today become a way of identifying a form of experimental rock music and its influence can be heard in groups such as Thinking Plague, 5uu’s, Sleepytime Gorilla Museum, Miriodor and Guapo. The RIO festival was restarted in 2007 and continues to be held annually in Carmaux in France every September. This year, Christian Vander’s Jazz/Rock/Minimalist veterans Magma are set to headline, and the festival website carries a prominent image of Kavus Torabi (Cardiacs, Gong, Knifeworld, Monsoon Bassoon) who also recommended Henry Cow to me years ago after a gig, who has seemingly become a poster boy for the progressive genre.

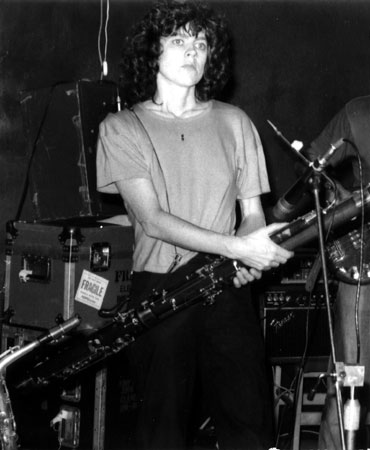

Unrest was recorded at Virgin’s Manor Studios in February and March of 1974 and was dedicated to Robert Wyatt and Guru Guru/Neu!/Faust and Spacebox bassist Uli Trepte. The classically trained Lindsay Cooper joined the band on oboe and bassoon in 1973, augmenting the core members of Frith, Cutler, Greaves and Hogdkinson. Having recently come off tour with Faust, it soon became obvious that the group lacked enough written material for a full length LP. Due to time constraints, but also taking Faust’s use of the studio as compositional tool as inspiration, the band experimented with processes that exploited the possibilities of tape manipulation as applied to improvised pieces. The general critical consensus was that the composed pieces, comprising most of the first side of the LP, were the most successful. Indeed, they represent some of the best music the band ever recorded and there is much beauty to be found amongst the unusual time signatures and atonality also present. Although the improvised pieces are more varied in their strengths and weaknesses, the importance of those studio experiments should not be underestimated. In the same interview referred to above, Fred Frith (who was also the most prominent band member in terms of writing the composed pieces), said: ”Making Unrest was a wonderful and radical experience… it set the tone for everything I’ve done in the studio since, giving us a deep understanding of the possibilities of the medium."

As one of the (often valid) criticisms of the progressive genre is that over reliance on musical virtuosity can result in a stifling of creativity, strategies employed to work against this tendency are all the more important. The kind of spontaneity engendered by group improvisation allows for ways of thinking outside the box, which may be why Fred Frith deploys such unlikely methods of guitar attack as chains and handfuls of rice when currently performing live.

The album opens with the Frith composition ‘Bittern Storm Over Ulm’, in which he takes apart the Yardbirds’ ‘Got To Hurry’, putting it back together with additional bars, beats, half-beats and deceptively ‘pop’ sounding hand claps – all within the space of a little over two minutes. It starts simply with laid back, rolling drumbeats and sustained guitar notes, the music initially full of spaces but narrowing the gaps as it progresses, Cutler’s drumming slowly winding the increasing pace, precise yet loose, clockwork being stretched like taffy and Cooper’s bassoon adding deeper, earthier tones. A similarly successful deconstruction of a blues tune appears as the first track on the second album by Belgian avant-rock band Aksak Maboul, with Frith and Cutler guesting on the re-imagined Bo Didley track ‘A Modern Lesson’. Next up is John Greaves’ ‘Half Asleep Half Awake’ – one of the album’s loveliest tracks. A gentle piano motif stirs as if slowly shaking off the shackles of sleep, a beautiful pastoral-sounding oboe melody takes the track to the halfway mark before the whole thing explodes with Cutler’s wonderful, octopoid drumming and Frith’s stretched out guitar notes, returning finally at the end to the gorgeous piano refrain fading slowly out.

Inspired by Bartok’s use of the Fibonacci series, Frith developed the harmony and beats of ‘Ruins’ by similarly utilising the numerical series. Fibonacci numbers are closely related to the golden ratio, used in art and architecture, and can also be found in natural biological formations such as the branches of trees, flower petals or the spiral of a snail’s shell. Like most of these tracks, a strong melody is established early on, then broken down into a more chaotic sounding middle section before being reestablished at the end.

Side two opens with the short ‘Solemn Music,’ taken from Henry Cow’s music for John Chadwick’s version of The Tempest, which is the only section of the that piece to have been released. Although I was unaware of the connection at the time, its eerie ambience taps a similar vein to Art Bears (a later Cow-related project) tracks that I used to accompany my Shakespeare theatre production project in my first year at university. The rest of the tracks on the album are the improvised numbers using the studio as compositional tool. Although I think it would be fair to say that these tracks seem rather bewildering at first, given the strength of the composed tracks that precede them, there is still much that rewards an open-minded and attentive listener. The chaotic ‘Upon Entering The Hotel Adlon’ and the beautiful, slow reveal of ‘Deluge’, that ends with a lovely, melancholy piano and vocal by John Greaves, are entirely memorable in their own right. The 1991 East-Side Digital reissue contained an extra two bonus tracks taken from the original sessions, ‘The Glove’ and ‘Torchfire’. I had this version for years, and it always struck me how quiet the sound level on the CD was. Recently I picked up the audiophile vinyl reissue on Chris Cutler’s own Recommended Records and the sound quality is far better. When I asked Cutler to comment on his experience of recording Unrest via email, he had this to say:

"Lindsay had just joined and we’d had little time to rehearse or write new music with her in mind, so we went into the Manor with nowhere near enough music to complete an album. But, after our experience with Leg End we were fairly confident that, one way or another, we could assemble new material in the studio through a process of improvisation, selection, discussion, editing, overdubbing customised writing, processing and mixing. Which we did. It was an experience that probably did more to bind the band together than anything since our marathon month writing for The Bacchae; and we were very pleased with the result. For us it was a breakthrough. We were so pleased, in fact, that we invited the Virgin staff to a listening (it was still operating as a kind of family then), and were pretty crestfallen when no-one seemed to be very enthusiastic. In fact, management’s general lack of interest in the band was what made us pull out of the Agency and start organising our own tours and concerts soon thereafter.

"I think side two of Unrest is still one our better achievements; I’d select ‘Deluge’ as a

great piece of music even now; and it’s a piece that could never have been scored; it was a pure product of realtime playing and collective assembly. It’s made of no more than a 50 second loop, some of ‘Ruins’ played at half speed, several layers of minimal overdubbing, a mix-idea and a concept that grew out of itself. Working this way, you learn to listen differently. And think differently. The way side two reads is… complex; it fits together in a kind of narrative way, and it also makes a lot of unintentional commentary on different kinds of musical form; it’s a snapshot, and it couldn’t be made today. For us improvisation was essential, and at least 40% of any gig would be improvised. it may be harder to listen to, but it can be more rewarding too; there’s a truth there."

After Unrest, Henry Cow continued in typically eclectic fashion, releasing a collaborative LP with Slapp Happy (Anthony Moore, Peter Blegvad and Dagmar Krause’s ‘naive pop’ group) entitled Desperate Straights, before attempting to combine both groups under the Henry Cow banner for In Praise Of Learning, and finally slimming back down to a quartet for Western Culture. After the band had split, Cutler, Frith and Krause continued under the more song-based guise of Art Bears. Revisiting their music as I write this piece, I find that 15 or so years after my first exposure to it, it still has an incredible power and totally unique sense of identity. It also represented for me, an opening into a world of music I had only previously suspected might exist, and which continued to reveal itself to me in a whole host of subsequent releases by Henry Cow affiliated musical projects.

There really are far too many to mention but at the very top of a list of other truly great ‘connected’ albums/projects, I would have to choose The Fred Frith albums, Gravity and Speechless and also the amazing film about Frith by Nicolas Humbert and Werner Penzel – Step Across The Border. John Greaves’ Kew. Rhone – which I only discovered whilst writing this piece. The Art Bears’ The World As It Is Today, and the two albums by News From Babel. Further stylistically afield and most interestingly for me, connecting to the kind of New York avant-garde vibe that Frith encountered when he moved there in the early 80s, there are his bands Massacre (with Bill Laswell and Fred Maher) and Skeleton Crew (with Tom Cora and Zeena Parkins), and of course, his participation of perhaps the greatest avant-garde ‘supergroup’ of recent memory, Naked City. Frith is currently Professor of Composition in the Music Department at Mills College in Oakland, California and continues to play in a number of groups, including Maybe Monday (with saxophonist Larry Ochs and koto player Miya Masaoka) and Cosa Brava (with Zeena Parkins, Carla Kihlstedt, and Matthias Bossi). Cutler produced a book on the political theory of contemporary music, File Under Popular, in 1984, and continues to run his independent record label Recommended Records, whilst participating in a wide range of groups that have included Cassiber, The (ec) Nudes, The Science Group and HeXtet, as well as working with such figures as Pere Ubu’s David Thomas and The Residents. Tim Hodkinson formed his post punk outfit, The Work, in 1980 and is also known for his involvement in the free improvisation group Konk Pack and the ‘shamanic jazz’ troupe K-Space, as well as a number of solo albums. John Greaves, who was also a member of the Canterbury-scene inspired groups National Health and Soft Heap, likewise released a number of solo albums and performed Kew. Rhone in June 2007 at the Tritonales festival in Paris. Despite being diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in the late 70s, Lindsay Cooper co-founded the Feminist Improvising Group, released solo records such as Rags and The Gold Diggers, as well as writing scores for film and television. She sadly passed away in September of last year and her obituary in The Guardian recalled her "imaginative, spirited, humorous and courageous approach to life".

This article is dedicated to her.