Pardon what appears to be an opening digression, but there’s a point here, which I’ll get too in reasonably short order, I promise.

There was something oddly, disconcertingly, hard-to-put-your-finger-on familiar about Avengers: Age Of Ultron this summer – beyond, obviously, the fact that all the key players had been introduced and built up as three-dimensional characters via a string of preceding films, and notwithstanding their appearance for years beforehand in the comic books the Marvel Cinematic Universe films are based on. Rather, what I found nagging at the back of my mind was the formal similarity the film bore to… something I couldn’t quite place. In particular, the way that the film’s centre of gravity was located not around the expected big guns – the smart-alec Iron Man, the haunted Hulk, or Thor, the demigod with the neat line in self-aware humour – but on the relationships developed by Jeremy Renner’s Hawkeye and, to an only slightly lesser extent, Scarlett Johanssen’s Black Widow, neither of whom have, as yet, had their own film out. Eventually, what I’d recognised in there finally hit me. It was reminding me of a late-period Wu-Tang Clan album. Not Forever, the record which, in terms of project cycles, Age Of Ultron appears to be the corollary of; but Iron Flag or 8 Diagrams, records where the Clan members you instinctively look to for highlights are subtly but forcefully overshadowed by less heralded members of the group. They come to the fore by dint of their obvious work ethic, the simple fact of their relative ubiquity on the record, and ultimately because the quality of their contributions wins you over. In the same way Iron Flag belonged to Inspectah Deck, or how you often found yourself thinking that the best verse on an 8 Diagrams song had come from U-God, so I ended up feeling that Age Of Ultron was Hawkeye’s film.

They may have patterned their concepts on kung-fu and mafia movies rather than superhero ones, but it’s not just Method Man’s occasional use of a persona called Johnny Blaze that amplifies the similarities between the Wu-Tang’s discography and the MCU. Rza’s first five-year plan for the Staten Island crew has long been the stuff of music-business legend – the deliberately opaque collective, more brilliant rappers than you could shake a stick at, introduced to the world by a group album but with the contract structured to allow each member to sign their own deals and make solo records. After Enter The Wu-Tang set the group’s stall out, the first phase of the master plan called for solo LPs, on which each featured member would be supported as required by fellow band mates, and would benefit from Rza’s production.

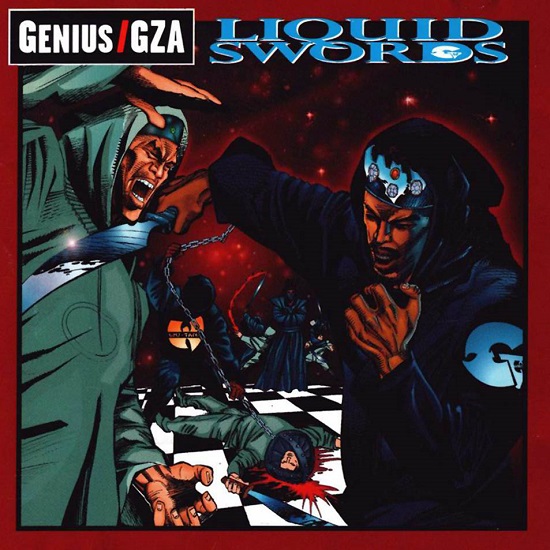

So instead of seeding the individuals first, then having them team up – the "form like Voltron" comparison included during a sampled radio-interview interlude on Enter The Wu-Tang isn’t quite accurate – the Clan’s strategy called for the collective to hit first, then splinter and send out its constituent parts to stake claims across the hip hop map before regrouping. First out of the blocks was Method Man’s Tical, on Def Jam – an obvious choice in every regard, the Clan’s most conventionally charismatic emcee hitched to hip hop’s most iconic imprint, though the partnership would never quite scale the heights one might instinctively have expected. Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s idiosyncratic, iconoclastic, inspired Return To The 36 Chambers followed, on Elektra, around the turn of the year. Rza’s other group, Gravediggaz, released an album and then in the summer of 1995, Raekwon’s Only Built 4 Cuban Linx and Gza’s Liquid Swords – both worked on in parallel, in Rza’s basement studio, over the preceding year – were unleashed.

It’s fair to say those two records reaped the full critical – if not necessarily commercial – benefits of the years-long preparatory effort. …Cuban Linx tends to be the purists’ choice, and its iconic status to hardcore fans remains undimmed. Liquid Swords – perhaps in part because it was released by Geffen, a label largely untested in the hip hop market, who promoted Gza’s album as if it was an independent rock record because those were the routes to the public that they best knew how to exploit – eventually got the nod from the non-rap-specialist music media and it tends to be the Wu-Tang album that people who wouldn’t call themselves hip hop specialists like the best. While "hip hop album rated highly by people who don’t like hip hop very much" is hardly a ringing endorsement, in Gza’s case it’s an evaluation we can trust. This may not be the unequivocal choice of everyone with a view on the matter, but if it’s not the best of the first phase of Wu-Tang albums, it’s one of the top two; and that means it’s among the greatest hip hop releases of the 1990s, and one of the best of all time.

It’s also, in a sense, the second Wu-Tang Clan album, in that it’s the first of the solo albums to include all nine original founding members of the group. Tical is very much a conventional solo LP, with just a third of its tracks featuring other emcees. Six members appear alongside Dirty on his album, but there’s no sign of Deck or U-God. Dirty doesn’t appear on …Cuban Linx (unless you count ‘North Star (Jewelz)’, a bonus track that only appears on CD versions of the album and wasn’t considered a canonical part of the whole when Get On Down released their Purple Tape collector’s edition in 2012.) Dirty’s and U-God’s contributions to Liquid Swords are limited to choruses, but everyone who contributes a verse offers something meaty and meaningful. Indeed, there’s a case to be made that some of the contributions here (Meth’s two verses on ‘Shadoxboxin”, Ghostface Killah and Rza on ‘4th Chamber’, even Deck on ‘Cold World’) are among each man’s greatest moments on record.

In fact, there’s so much of everyone else it’s remarkable that Gza doesn’t get overshadowed on his own album – but it’s conversely a mark of his artistic authority that the record remains definably and definitely his own. As well as those stellar contributions from the other Clan members, acolyte/associate Killah Priest doesn’t just take a (great) verse on ‘4th Chamber’, he is – bafflingly yet brilliantly – given the whole of the closing track, ‘B.I.B.L.E. (Basic Instructions Before Leaving Earth)’. This, too, manages to work as a demonstration of Gza’s personality: Priest was, after Master Killa, one of Gza’s "students" (the kung-fu concept of the master and the pupil lives large in Wu-Tang mythology, and Rza in particular has spoken at several points over the years of how members of the group brought other emcees to the collective and took them under their wing, offering support, mentorship and tutelage) and giving him the closing track feels like an act of baton-passing and fatherly encouragement. If one were of a mind to extend an irrelevant comparison way beyond breaking point, one might also muse that Liquid Swords thus [SPOILER ALERT!] ends in a similar way to Age of Ultron, by introducing the audience to the next generation of lyrical superheroes.

(Please forgive the digression, but there’s a footnote worth inserting at this point: readers wanting to ignore this and crack on with the Liquid Swords-specific stuff, please feel free to re-join us at the appropriate point below.

In the late 2000s, a court case brought by Ghostface against Rza over royalties on early Clan solo albums revealed a curious truth to the outside world. The Clan member whose name was on the label – the titular solo artist; ie, Meth for Tical, ODB for …Dirty Version, Rae for …Cuban Linx and Gza for Liquid Swords – got half of the songwriting copyright on the songs that were released on their albums. Regardless of who appeared on the track, the split for royalties was half to the producer, and half to the "solo" artist – and on the first Clan album, every member of the group got publishing royalties from every song, even if they didn’t appear on it. In a 2004 interview, Method Man told me he made quite a tidy sum from his cut of the royalties after Lauryn Hill sampled ‘Can It Be All So Simple’ on her song, ‘Ex-Factor’, even though Meth didn’t appear on, or contribute any work towards, that particular Wu-Tang song.

"Wu-Tang Clan should be considered as one entity, one lyric, as the vocal part of every record – that was our original deal," Rza told me in an interview in 2008. "This is a verbal deal we had: we said, no matter who put out a solo album, that whoever else raps on that album, they get no publishin’. The publishin’ will go to the artist whose album it is. And we’ll do that for each one of us to each other. On …Cuban Linx, for instance, Ghostface is not gettin’ no publishin’ – all of it goes to Raekwon."

This changed, though, with the 1996 release of Ghost’s solo debut, Ironman, and royalties were broken down more accurately to reflect lyric-writing input from guests on specific tracks. "That’s years later," Rza pointed out. "Method Man had signed a publishin’ deal with BMG, Raekwon signed a publishin’ deal, Rza signed a publishin’ deal, Ghostface even signed a publishin’ deal. Now you got a third party speakin’ up for the client, so now you gotta give it to them. And that’s why, when we got to Ironman, it was different."

The court case came about, in part, because Ghost – or those working on his behalf, at least; Rza stressed that there was no animosity on a personal level between the two men – felt he’d been short-changed compared to his bandmates and the monies they’d received for those earlier solo albums, most particularly on …Cuban Linx, where he appears on almost every track, yet would have received no publishing royalties whatsoever.

"Ghost still was able to keep all his advances and everything for his self, but the royalties? Raekwon would get royalties," Rza continued. "So I said, ‘Yo, that’s something for you and Raekwon to settle.’ Because he said, ‘How come on my album you didn’t do the same thing?’ I said, ‘Yo, your album was the first album that we didn’t do it on.’ He said, ‘How about the Gza album?’ I said, ‘Nah, the Gza album, you didn’t get no publishin’ – everybody didn’t get no publishin’! Gza got the publishin’ on that shit’."

The question naturally occurred to me: does that mean that Gza received 50 per cent of the songwriting royalties for ‘B.I.B.L.E.’, a track on which he does not appear? Rza thought for a moment, before answering.

"Gza may have got the publishin’ for ‘B.I.B.L.E.’!" he chuckled, clearly only asking himself the question for the first time. "Gza may have got the publishin’ for ‘B.I.B.L.E.’. He may have gave that to Priest, but I doubt it very seriously. I think Gza got the publishin’ for ‘B.I.B.L.E.’. I know, that’s deep, right? But listen, that’s how… Look, on the song ‘Method Man’? Who was rappin’ on that song? Method Man, and me producin’ it, right? But on ‘Method Man’, if you look at it, it has all nine of our names. Everybody gets publishin’ off ‘Method Man’."

For his part, Gza was largely unconcerned.

"Well, according to the paperwork, that’s how it was," he said, when I put the question to him later. "But in those early stages I don’t know what was what. Because we used the same lawyers, which was a conflict – whatever lawyer Rza had was the lawyer we used. I don’t really know much. I mean, I haven’t really received many royalties from Liquid Swords. I don’t know what Priest received. He got royalties that’s been sitting for a while, on his own personal… I don’t really know, but that was the way it was supposed to go down, and that’s the way it was. It’s no big deal. I’m not suin’ him. But that’s how it was at first – I think it did go down like that. The one whose album it was got the majority of the splits. We all came into the business… we had no knowledge of publishin’ an’ royalties and things. We were just happy to make a song.")

MEANWHILE, BACK AT LIQUID SWORDS…

Whatever else it may have going for it, Liquid Swords is first and foremost a feast for the student of lyricism. At the heart of its considerable appeal is a fascination that springs from its maker’s ability to at once demystify the writing process, and beguile with poetic sleight of hand. This record first engages, then enraptures and eventually enlightens because of the way Gza writes about the way he writes. When, early on in the title track, he says: "I flow like the blood on a murder scene," it isn’t just a metaphor or a brag – it’s a codified and oblique explanation of the nature of his art, using an idiomatic picture to stretch beyond imagery and seep in to a description of how his style is constructed. Similarly, when he tells us that his sound has a "wide entrance, small exit – like a funnel/so deep it’s picked up by radios in tunnels", he fuses analogy and simile with a kind of example: this isn’t just him showing off, arguing that he’s deeper and cleverer than the rest (though he is) – it’s Gza as stage conjurer, performing the magic at the same time as he’s showing us how he did it. It’s remarkable: in an art form where advantage over the competition is zealously guarded, Gza lays the tricks of the trade bare. It’s almost as if he’s daring others to try to turn his tools against him, safe in the knowledge that they won’t have the first clue how to use them. (It’s perhaps over-egging the Marvel comparison, but I’ll say it anyway: Gza uses his writing technique like Thor’s hammer, safe in the knowledge that mere mortals can’t even pick it up, never mind wield it in combat.)

Another couple of points worth making about that opening track concern the way it sets up some of the album’s themes and aspirations, and emphasise how Gza and Rza – cousins, and the two most experienced members of the Clan – were able to perform the kind of musical alchemy they achieve so consistently throughout the record. The song has a chorus, which is interesting enough in and of itself (Wu-Tang songs don’t always). Both producer and principal lyricist work hard to make that chorus have a kind of totemic role not just in the song but across the album. Musically, all Rza does is loop one section of the Willie Mitchell track ‘Groovin” – which also appears in ‘4th Chamber’, and comes from the Hi Records catalogue which, along with Stax/Volt, provides the backbone for seven of these tracks – but he chooses a bridging section with an off-kilter feel and unusual instrumentation: the effect is almost to create a new genre out of a sound that is familiar yet alien, cyclical yet unresolved, recalling something buried and ancient yet sounding compellingly new. Over it, Gza spins a yarn that sounds like he’s sketching hip hop into pre-history: "When the emcees came to live out their names, and to perform/Some had to snort cocaine and act insane before Pete rocked it on." It’s like he’s found the words carved on an ancient stone, overgrown with moss and ivy, and has uncovered them and is bringing them to light. And in a way, what he’s done is a bit of personal archaeology.

Along with Rza, who’d had a pre-Wu-Tang deal with Tommy Boy (he was signed as Prince Rakeem, only released an EP, but says he had not just one but two solo LPs finished and ready to go by the time he was dropped), Gza made records before the Clan. His 1991 Cold Chillin’ LP, Words From The Genius, isn’t a bad record by any stretch of the imagination, but stood next to Liquid Swords it’s clearly the callow youngster at work, not the mature artist. It finds him a little short of developing a singular style: he’s not exactly overawed by labelmate Big Daddy Kane, but there are moments where he seems to pattern elements of his delivery on the established star. Nevertheless, he chose to reference it here, at the opening of what we have to consider is his true solo debut (while Gza is a familiar contraction of Genius, and the record is credited to Genius/Gza as if both were part of the one name, his first post-Enter The Wu-Tang solo single was credited just to Genius, which was the name his Cold Chillin’ album was released under. ‘Liquid Swords’ – released as a single just ahead of the album – is the first time a record came out by him with Gza on the cover, so in effect it’s that persona’s first release). On that first album there’s a track called ‘Those Were the Days’. Here’s its second verse:

"Now it’s high school, lunch room’s the scene

and I’m ready to flip the routine.

In the cafeteria, period three –

and here I come with the JVC.

I go in my pocket and pull out a mic,

plug it in, ‘Check one, two. Alright!

Now – who wanna show and prove their emcee skills?’

A brother stepped forward and tried to get ill

but when it came time to live out his name

he kicked rhymes that all sounded the same.

I did him in with a matter of time

and he was done with one victorious rhyme.

He was shocked because he knew he was rocked,

along with his classmates from off his block.

Yo, I’m tellin’ you, I flipped his whole crew!

One against one or one against two,

or three or four brothers who swore they can rhyme,

battled me and got taken out every time

from my style and my dope profile

plus the period of time that I rocked for a while

as a motivated, dominated supreme force –

cultivated, activated cream and source.

The wise educated and born to be –

the one who would flip an emcee."

Very few people bought Words From The Genius on its release and not many bothered when Cold Chillin’ reissued it in 1994, either. So the vast majority of those hearing Liquid Swords in 1995 wouldn’t have made the connection. It’s possible Gza didn’t either – in a 2010 Wax Poetics article on the making of this album, he recalled that the chorus was based on a routine he, Rza and Dirty had been doing as kids in the 1980s. But there’s something that feels, in retrospect, significant and important that ‘Liquid Swords’ (the song) opens with lyrics that echo a tale of battles in a school cafeteria. It’s an evocation of an era of lost innocence, even if the lyrical combat it depicts is never less than total warfare. The playfulness and experimentation conjured by that look back to lunchtime open-mic sessions is something that Gza clearly still carried with him. It’s also instructive, when listening back to the album with the benefit of hindsight, to re-read what sounded strange and ancient – perhaps an attempt to reinforce the connections between the Wu-Tang Clan of Staten Island in the 1990s and the Wu-Tang Clan of medieval China – was in fact the equivalent of a hip hop skipping game.

And that’s the other thing the title track brings up: the album’s use of dialogue from the film Shogun Assassin as a linking device, implying an overarching concept which holds the album together. A great deal was made of this in reviews and coverage at the time of the album’s release, and it’s clear that the album’s filmic qualities, and the suggestion of a narrative running through it that the samples from the film implied, were a big part, if not of its appeal, then in conveying an approachability to the record for listeners who perhaps wouldn’t otherwise have considered spending time immersing themselves in what is, in the final analysis, a pretty intense hour of pure hip hop. Strange as it may seem now, this apparent linking concept wasn’t part of the album’s creation, but applied after most of the rest of it was finished. As for any narrative links between the record and the film being intended, that’s a non-starter: Gza hadn’t even seen it.

"According to the theme, an’ the scoring behind it? Yeah, I think it was a concept album," Gza told me in a 2008 interview. "I think Rza made it a concept album. I don’t think it was until he scored it with all the other stuff. I think it was already almost there, but when he tied the theme an’ the skits an’ all that? It was even at the last minute. We were masterin’ the album, and he sent one o’ the assistants out, an’ he said ‘Go get me the Shogun Assassin‘. Last minute! He went an’ got that movie, an’ that’s where all those skits came out. So you see the chemistry between myself and Rza. Because that wasn’t even in the picture! We didn’t have that ’til the last minute when he said ‘Yo, get me Shogun Assassin‘ – a movie I’ve never watched before, at all – and he used it for the album."

Shogun Assassin had appeared on the record before the addition of the interludes at the last minute, though. ‘4th Chamber’ – arguably the standout highlight of a record filled with them – uses a sample from ‘Assassin With Son’ by the Wonderland Philharmonic, from the film’s soundtrack album, although it’s a sample Rza has messed with, turning it into something almost like a riff replayed on a Stylophone. Each of the four verses is outstanding, sketching Wu-Tang into wider and more expansive mythologies: Ghostface claims he "ran the dark ages/ Constantine the Great, Henry the Eighth/ Built with Genghis Khan", Killa Priest says his "dome-piece is like ancient stones in Greece/ My poems are deep – from ancient thrones I speak". Rza’s astonishing verse invokes plagues ancient yet modern ("six million devils just died from the bubonic flu/or the ebola virus under the reign of King Cyrus") before making up a mnemonic as a nuclear-physics-based warning as his way of saying "Peace" to end his turn on the mic ("protons, electrons always causes explosions"). For his part, Gza offers a narrative about tax-evasion, revenge and education, all culled from the contemporary but styled to sound timeless ("sons are born and guns are drawn/ clips are fully loaded, then blood floods the lawn"). He also reveals something of the making of the album, referencing the fact that Rza had very deliberately structured the backing track so that each verse is shorter than normal – a key part of how the song retains such an unusual and unsettling atmosphere. He mentions that he’s had to "truncate the length one tenth" then says that when Rza "shaved the track, niggas caught razor bumps".

‘Labels’ attracted plenty of attention at the time, and gave Gza a formula he has revisited on subsequent albums – taking a concept and writing a lyric that allows him to work in as many brand names and associated references as possible. Rather than just becoming lists, though, he tries to make a narrative out of the conceit. "One thing about these songs that I must say," he told me in 2008, "I don’t sit down an’ brainstorm an’ say, ‘I need to do another ‘Labels’.’ They always happen accidentally. Someone always says something that sparks that idea to the song. There’ll always be a line… Like, when I did ‘Labels’, someone was like, ‘Fuck Tommy, he ain’t my boy.’ And that’s when it came into my head – ‘Tommy ain’t my Boy.’ And it sparked a song. When I did ‘Animal Planet’ [a similarly constructed track on the 2002’s Leged Of The Liquid Sword, involving lyrical references to different species] I was watchin’ National Geographic, and it was something the narrator said about the polar bears feastin’ on the blubber of seals. An’ I was like, ‘Oh – a whole song!’ That’s the animal world, but I thought about humans: animals are more intelligent than humans nowadays, accordin’ to their conduct an’ their behaviour. Of course they’re wild and they hunt, but we do the same thing, and we’re humans! We should be more intelligent. We shouldn’t be robbin’, stealin’, killin’, raping. You know? Crazy. With ‘Publicity’ [a track on Beneath The Surface that included names of dozens of hip-hop magazines] I was in a studio one day. There weren’t any Clansmen – I think it mighta been [associated artists] Killarmy, Sunz o’ Man – one of them where they were in there. And I picked up some dude’s notebook – someone had left some rhymes lyin’ around – and it was Timbo King, from [another Wu-Tang affiliated group] Royal Fam. He had one line where it said, ‘My Rap Pages Are The Source.’ And I was like, ‘Wow, that’s an incredible idea.’ He wasn’t thinkin’ how I was thinkin’ when I looked at it. I called him and said ‘Let me use that’, and he said ‘Sure, use it.’ An’ then I made ‘Publicity’."

‘I Gotcha Back’ was the first song recorded: indeed, it was the first to be released, as part of a film-soundtrack project which also unleashed Raekwon’s ‘Heaven and Hell’. To add to a sense of burgeoning confusion about the Clan, their nomenclature and their various business affiliations, it was on Loud/RCA (the label that Raekwon’s solo album, the Clan’s group recordings and, in the fullness of time, Inspectah Deck’s solo material were also released through) and, as noted earlier, the artist credit was simply Genius, with no mention of the contracted form. It’s perhaps unsurprisingly transitional or basic, but forms a thematic and sonic bedrock on which most of the rest of the record is solidly built. There’s things going on here that feel like rough drafts to a more refined approach – the way he’ll play with mnemonics and acronyms that’s still a little gauche in execution even as it’s daring in conception ("What is the meaning of crime? Is it criminals robbin’ innocent motherfuckers everytime?").

‘Labels’ is one example of a singular writer revelling in his craft; ‘Cold World’, a scintillating collaboration with a similarly visual and acutely metaphorical Deck which became a surprise choice as a single, is another – both men sketching street tales with simplicity, clarity and poetic depth. ‘Swordsman’, perfectly placed towards the end of the record where Rza’s portentous beat and Gza’s dazzling, tight lyric feel like an ominous preamble to a clash-of-civilisations climax, is a different approach again. Here he writes, yet again, from inside his present, and about how he approaches hip hop as a writer, yet the end-product is a song about religion, philosophy and history, explaining albeit obliquely how his immersion in the teachings of the 5% Nation of Islam gave Gza the tools to deconstruct and overstand his surroundings and the society he is a part of, and appearing to redraw Clan mythology to include the slave trade.

That he’s a singular lyricist is abundantly clear throughout the record. How and why he came by this took me some years to fully appreciate. In that 2008 interview, the penny began to drop. He doesn’t just think about rap differently from everyone else – music means something else to him entirely. We were talking about his then current tour, where he was performing this album in its entirety, and I wondered whether he ever felt restricted by the need to constantly revisit old material.

"It doesn’t hold me back to do old songs – never," he said. "Maybe these weak-ass, non-lyrical emcees feel that way – they always wanna do new shit. I mean, if you don’t know where you come from, how can you know where you’re goin’? It’s just inspiration to me. I’m inspired by… You don’t even know the stuff I’m inspired by. I can write 20 more albums, I’m inspired by so much! An’ they can all be different, ‘cos that’s how I get down. I can write about water, an’ you’ll never know I’ll be writin’ about water, it’ll be so interestin’. I will! And you will hear that! Wind – I can write about wind, I can write about weather."

It’s clear he just hears things differently to most. In another interview, he said: "I don’t really listen to much anyway. I ride in the car with everything silent. I listen to the wind. I open the window and listen to the wind blow, listen to the cars pass. You know? ‘Cos that’s music in itself. Anything that has sound and has life? That’s music."

That singular approach to listening informed a unique methodology for creating music. It also helps explain the depth of connection the album was able to make. Beyond being appreciated, studied and enjoyed by fans, the album feels like it has a life-force running through it: that force may not have proved powerful enough to save lives, but it’s come close.

"There’s always a story attached to a song," Gza said during another interview, in 2007. "That’s why you must have the greatest songs you can possibly make, because the greater the song the greater the story that’s attached to it. I met a person one time who was in a car accident, comin’ home from a school winter break, and in a snowstorm the car flipped over a couple of times, and in the car, her girlfriend died. She says all she remembers is layin’ in the snow, and everything was thrown out of the car, and she reached for a CD, and it was the Liquid Swords CD, and then she blacked out. And when she woke up, that’s what they told her – they found her holdin’ that CD, that was the only thing she had in her hand. Somethin’ about that whole experience and that moment made her reach for that CD. It’s just amazing."

It is a remarkable record; a ten-out-of-ten, five-star masterpiece. But it’s not perfect. (Those two statements aren’t mutually incompatible: great art would be less successful if it was free of the flaws that make it relatable and emphasise its connection to the human spirit.) Its maker – who later described himself in a lyric as "the obscene slang kicker with no parental sticker" – would do it slightly differently if given the chance again.

"When I’m listenin’ to the album over and over, I always think o’ things that I could change, because I’m growin’, I’m developin’," he said in 2008. "I always look back at Liquid Swords and think, you know, I woulda said this different. I mean, I use a lot of profanity on that album. I wish I coulda not had any, an’ not had that sticker on it, because I wanna reach out to young and old: I don’t want people to be able to look at my album an’ say, ‘Oh, that shit got cursin’, I don’t want my kid to listen to this.’ So there’s always room for development. Always."

The records that followed Liquid Swords never seemed to connect in quite the same way, which seems more than a little unfair, as Beneath The Surface, Legend Of The Liquid Sword and Protools are all up there quality-wise, and Grandmasters – a collaboration with Cypress Hill’s DJ Muggs – is also a strong album. His verses on Clan LPs have remained undimmed highlights, ideas flowing as thick and fast as ever (a particular favourite round these parts is his contribution to Iron Flag‘s ‘Uzi (Pinky Ring)’, which begins: "From dark matter to the big crunch/the vocals came in a bunch/ without one punch," linking the act of one-take recording and flawless first-time performance to the origin of the universe, before ending with a couplet that compares hip hop to diamonds and asphalt). Perhaps that’s the problem: we don’t really listen to music today – digital ubiquity leads to superfluity; there are fewer people listening, re-listening and studying lyricists, and more emphasis placed on hearing, reacting, commenting and moving on quickly to the next box-ticking exercise in music consumption. The apparent need we have to codify, rate and annotate means we acknowledge Liquid Swords as a classic, but don’t pause to consider the possibility that the records made since could be worth the same sort of attention. A long-delayed new Gza album – its title, Dark Matter, excitingly suggesting an investigation of some of those ‘Pinky Ring’ ideas – is due in the autumn, and provides an opportunity to redress this wrong as one of hip hop’s most compelling superhero sagas continues.