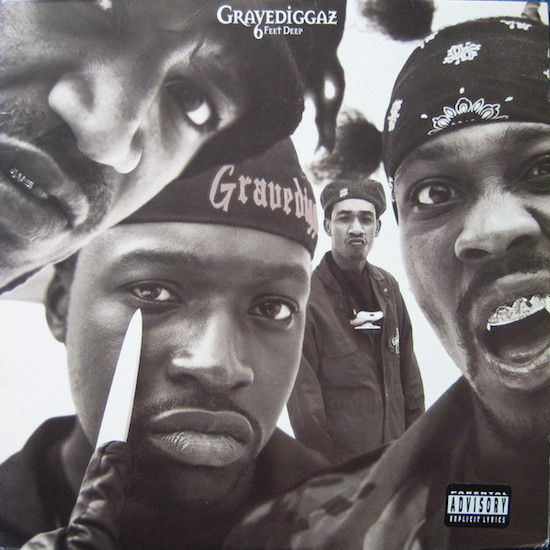

Here are things that New York’s Gravediggaz may legitimately, albeit not conclusively, claim. They were the first hip hop supergroup, and they were the first horrorcore group. Others may dispute those claims – fans of Geto Boys, in particular, might have something to say about the second one.

And here’s something that surely can’t be argued; not, at least, by anyone with ears and so much as a passing interest in hip hop: Gravediggaz’ first album, 6 Feet Deep, is a stone classic. Its ominous beats, its gleeful and macabre lyrical invention, its (in both senses) black humour, its satirical heft – all of it was held together by expert hands of Prince Paul, who produced the bulk of the album but took care not to overshadow it or stamp his personality on it at the expense of his fellows’.

Prince Paul has called it his favourite among all the records he’s made. Fêted for so brilliantly turning hip hop on its head with De La Soul’s Three Feet High And Rising, he was badly knocked back when the follow-up, De La Soul Is Dead, was deemed to have all too accurate a title by the industry at large and – so he felt – his own label, Tommy Boy. That album may now be highly esteemed, and Prince Paul’s own work on it acclaimed, but at the time he was depressed and felt written-off, discarded, on the skids. (That he went from Three Feet High And Rising to 6 Feet Deep may just be a coincidence, but it neatly tracked his perception of his fortunes, and his feelings.) He opted to put his gloom to good use, creating beats that echoed this dark state of mind. He approached what would soon be the other three Gravediggxaz; he recalls it was RZA (then still a solo artist on Tommy Boy going by the name Prince Rakeem) who, upon hearing those sinister foundations, came up with the group’s concept. That was also how RZA acquired his new name. Each member chose a suitably horror-inflected handle. Prince Paul became The Undertaker; his former Stetsasonic bandmate, Frukwan, The Gatekeeper. Another Tommy Boy solo artist, the late Poetic, would be The Grym Reaper (a nod to his previous group, Brothers Grym). Prince Rakeem was The RZArector – RZA, for short.

That was in 1991.

The three years that passed between the formation of Gravediggaz and Prince Paul finally obtaining a record deal for the group were crucial ones, and a missed opportunity. In 2013, Prince Paul told Chris Pattinson of HipHopSite.com, “The thing is [6 Feet Deep] came out just at the time when Craig Mack and Biggie Smalls came in. So we were doing one thing, but that other type of sound started popping. So when people looked at us like, ‘Gravediggaz? Ahh man, this is a gimmick!’ we kinda got swept under the rug. . . which kinda hurt my feelings because I really worked hard on that album. I think if it came out like two years earlier it would have been a big record.”

What if 6 Feet Deep had been released in 1991 or 1992? It would have emerged into a landscape where it made perfect sense, where it was the next progression. In hindsight, horrorcore is understood not simply as a schlocky sub-genre, but as a then novel means of addressing black life at street level – doing what rap had done from ‘The Message’ onwards, that is, and finding a new way of getting that message across. As Poetic put it on the opening ‘Constant Elevation’ – whose superb thudding and clanging backing track set up the album’s menacing atmosphere just so; and in that marvellous sing-song style that came to characterise the group as much as Prince Paul’s beats – “Critics say, ‘Go to Hell’, I go, ‘Yeah/Stupid motherfucker, I’m already here!’” That wasn’t just a turn of phrase. Dropped by Tommy Boy after one 1989 single, he had ended up indigent and homeless.

By 1991, Houston’s Geto Boys had expressed the ugliness of life at the sharp end for African Americans in terms that were luridly gothic – Grand Guignol, even – and Cypress Hill were about to bring the same sensibility to Latino gang life in Los Angeles. What Gravediggaz hit on was the idea of explicitly using the tropes of horror as a genre both to express their own personal disaffection, and to satirise social ills. That, of course, being a thing that modern horror as a mode does in general. What they were attempting was the hip hop equivalent of something such as George A. Romero’s Living Dead films – although their idiom was closer to EC Comics’ Tales From The Crypt.

But there’s a further dimension to this. In 1988 hip hop’s centre of gravity had been abruptly shifted west by NWA and Ruthless Records. Like any other form of pop, hip hop follows the money. And when it turned out gangsta rap was where the money lay, all of a sudden everyone was a gangsta, each new release vying to outdo the last for cold-blooded gruesomeness, justified on the grounds that it was simply portraying life as it is on the street. And maybe it was. There was no way for outsiders to know. But the more violent and nihilistic rap became, the more eager were those outsiders – as in, a largely white record-buying public – to throw money at it. That was quite the incentive to keep upping the ante.

Before N.W.A., to their considerable surprise, turned gangsta rap into a huge commercial force and L.A. into rap’s new epicentre, they started out with an often comical, almost theatrical approach. It was about the strength of street knowledge, yes – but it was first and foremost entertainment for the people whose lives their raps reflected. Racism and brutality on the part of the police is serious stuff; that didn’t prevent ‘Fuck Tha Police’ from being hilarious. The acts that came after, however, took a deadly serious approach; the only funny thing about Compton’s Most Wanted was their 1992 album title, Music To Driveby, which was as grimly inspired a joke as any until Gravediggaz themselves topped it with the original name for 6 Feet Deep (used, remarkably, on editions outside the States, which surely wouldn’t happen now): N*ggamortis.

What if, then, the original intention of Gravediggaz was to satirise not only the horrors America inflicted upon black people, but rap’s own response to them? In 1994, Gravediggaz were already a band out of time, albeit a damned good one; overtaken before they got off the starting grid not only by the new East Coast sounds noted by Prince Paul, but by Dr. Dre’s G-funk from the west. In 1991/92, their over-the-top, gore- and death-obsessed shtick would have represented an ingenious, musically advanced, tongue-in-cheek lampoon of rap’s dominant trend, yet one with perfect deniability – they were just, after all, doing a bit, one they could with a straight face claim to have borrowed from that other musical form beloved of alienated kids, and shunned and reviled by the forces of respectability: heavy metal.

It would also have been an affectionate burlesque – and, in a detail that lends some weight to this hypothesis, it would likely have come out on N.W.A.’s own label. Having been rejected at every turn, Prince Paul came within a whisker of signing Gravediggaz to Ruthless Records, which would have been a startling development in the regionally segregated and already feud-ridden world of hip hop. He met with Eazy-E, who on hearing their demo immediately offered them a deal. As Prince Paul described it to Pattinson: “I’m a big N.W.A. fan to begin with, people don’t realise how huge of a fan I was, so this was kinda going full circle for me. So I’m like, ‘Wow, he gets it! After all this rejection, Eazy gets it.’” (One of the stand-outs on 6 Feet Deep, lead single ‘Diary Of A Madman’, was constructed from already recorded verses into a courtroom scene without his bandmates’ knowledge by Prince Paul, who provided the parodic “white” voices. It’s true that comedic courtroom scenes go way back in black American culture – Pigmeat Markham’s ‘Here Come The Judge’ routine being the source for a series of novelty records – but it’s also, in this context, notable how closely Prince Paul’s format for the song runs to that of NWA’s ‘Fuck Tha Police’. And “Gravediggaz” itself doesn’t half suggest a play on “N*ggaz”, as in “N*ggaz Wit Attitudes”.)

Prince Paul balked when money-man Jerry Heller proposed a contract that “was probably one of the worst things I’ve ever seen in my life. It was like… what? Are you kidding me? It was horrible. So I still had a little faith, and I was like, ‘Yo, I’m gonna wait out for a better situation.’” That better situation eventually came via Gee Street, who had the nous to grasp what the group was up to and give them a shot. By then, things hadn’t just changed in rap as a whole; they’d changed in the band. RZA had assembled the Wu-Tang Clan, and in late 1993 their debut album Enter the Wu-Tang: 36 Chambers announced them as stars and altered the course of hip hop. It’s possible (indeed, Prince Paul seems to think it probable) that Wu-Tang’s success was what finally got Gravediggaz into the game.

So the chronology has it that Gravediggaz followed Wu-Tang Clan. But that wasn’t how it happened. And when you think of how both groups were structured – rappers with independent careers gathered around a producer who encouraged and liberated their creativity, with a collective aesthetic and brand based on a pulp-culture genre – all of a sudden Gravediggaz start to look like the prototype, and Wu-Tang Clan like the production model. Prince Paul sat in on some early Wu-Tang sessions, and noted the similar dynamic: “The beautiful thing was that they had so much respect for the RZA, every word that he said, the cats really respected and looked up to him; and to me it was really impressive because RZA had a lot of respect for me. So what was even more impressive at the time… as they looked up to him, he was coming to me and asking me, ’Yo, what do you think, Paul?’ And I was like, ‘Wow!’ It was a nice thing to come in to a lot of those sessions and get respect for being I guess what was called an OG at the time.”

25 years on, the musical greatness of 6 Feet Deep stands irrespective of its unfortunate timing. It’s there in the magnificent, morbid and very funny ‘1-800 Suicide’. In the swirling, woozy claustrophobia of ‘Nowhere To Run, Nowhere To Hide’. In the rock-guitar psych-out of ‘Defective Trip (Trippin)’, which calls to mind Gravediggaz’ Gee Street labelmates New Kingdom, another of the great lost bands of the era. It’s a wonderful, silly, serious, preposterous, profound album, a masterpiece in its own right, as well as a key piece of hip hop history hiding in plain sight.