You know who’s underappreciated in popular music? Chris Blackwell; that’s who’s underappreciated in popular music.

Which may seem an odd thing to say of a celebrated music mogul and inductee into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame, his name more often than not mentioned in tandem with that of Bob Marley – “the first third-world superstar” – in whose ascension to that status Blackwell was the key figure. But that is why Blackwell is underappreciated: because those are the terms of his reputation.

Without his Island Records label, the careers of not only Marley but Roxy Music, Brian Eno, Nick Drake, King Crimson and U2 would look very different; it’s a matter of guesswork as to whether we would know who all of them are. Which makes Blackwell an origin point for a quite extraordinary number and range of butterfly effects, considering the influence those acts and many others on Island have exerted. Pound for pound, Island’s impact is surely as great as any record company’s. But there’s more still. Blackwell wasn’t just – “just” – a sympathetic label boss with a remarkable eye for both artistic merit and commercial promise. He was vital in shaping much of the music himself. It was Blackwell who understood the potential of recording and promoting Bob Marley as he would have done a rock artist, rather than aiming him at America’s black charts and radio, where Marley would be under-acknowledged until his admirers in 90s hip hop and R&B brought his influence into play.

Blackwell whose co-production role on Catch A Fire saw the raw Wailers tapes from Kingston (the one in Jamaica, you wags, not the one on the Thames) polished and embellished at Island Studios in Notting Hill by top-rank session players. There’s a certain irony in this cornerstone of roots reggae, a genre prized for its purported authenticity, being a work of such craft and calculation. But look into the popularisation of almost any form of roots music, and you will see a similar story repeated. That’s how pop music becomes pop music; the authenticity becomes a matter of image and myth-making. Image and myth-making are fundamental to the pleasures of pop music, and the image and myth of the authentic is as valid a form as any, as long as we recognise it for what it is.

Yet Catch A Fire, significant as it is, isn’t the outstanding testament to Blackwell’s direct musical contribution. The outstanding testament to Blackwell’s direct musical contribution is the trilogy of albums recorded by Grace Jones between 1980 and 1982, that he co-produced.

Before we go any further, this would be a good point to stress: I do not mean to suggest Chris Blackwell is the auteur of the greatest work of Grace Jones. The auteur of the greatest work of Grace Jones is Grace Jones, and nobody who has the slightest awareness of Jones’s personality would intimate otherwise. Not because they are scared of her, although they should be, but because the idea that Grace Jones would relinquish the ultimate command of her creative destiny is next to unimaginable.

The story of ‘Pull Up To The Bumper’ is instructive in this regard. The groove that underpins the song was recorded by Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare, during the sessions for Warm Leatherette, but set aside because because Blackwell didn’t care for it, and considered it stylistically out of sync with the album: too close to R&B on a record that was attempting something altogether new and different. Titled ‘Peanut Butter’, it appeared as an instrumental b-side on a Junior Tucker single. On hearing that, Jones blew one of her famously imperilled gaskets, telling Dunbar to call Blackwell and demand its return: “I want back me riddim!” She co-wrote a set of lyrics; appearing on Nightclubbing, ‘Pull Up To The Bumper’ became her signature tune and one of her biggest hits. No question whose judgement was vindicated there.

What Blackwell did was provide the essential creative platform for Jones. Warm Leatherette wasn’t just intended to showcase a new type of music, although it certainly did that. It was also meant as the calling card for a grander project: the creation of an Island house band, studio and sound.

In Blackwell’s vision, the Compass Point Studios he had built in Nassau, the Bahamas in 1977 would take its place alongside Sun Studios, Muscle Shoals, RCA Studio B and Abbey Road as one of those spaces with an aura, a legend, an identity, an indelible association with a particular musical ethos. The band he installed there, who with no little justification labelled themselves the Compass Point All Stars, were intended to join the Wrecking Crew, the Funk Brothers, Booker T. & the M.G.’s, as one of the great house bands. The idea was that Compass Point would do for reggae what those studios and those collectives had done for rock & roll, for soul, for rock, for mainstream pop, for R&B, for country; it would both draw upon and develop it, retain its essence while shaping it into a modern, cosmopolitan, superbly crafted proposition with huge commercial appeal.

On some terms, Blackwell’s vision succeeded – Compass Point became a destination for major artists, throughout both its first run in the 80s, and its revival in the 90s and 00s before its managers deemed Nassau too dangerous for visiting bands and closed the operation down. On others, it fell short. Perhaps one flaw lay in what Blackwell initially identified as a strength: the lack of a sense of place in Nassau. Unlike, say, London or Nashville or Memphis, Nassau had no strong character of its own to impose osmotically on artists who recorded there. It served as a blank slate, leaving them free to create what reflected them. And for the most part, they did; but blank slates, by definition, have no distinctive quality of their own. Think of all those other studios, and bands, and you can think of multiple pinnacles; a wealth of artists and records who represent what they stood for. With Compass Point, nobody comes close to Grace Jones. If you want to know what Compass Point stood for, where it peaked, then you need to look at where it started: that trilogy of albums. Other wonderful records were made there: Tom Tom Club’s first album, and the absurdly undervalued Robert Palmer’s sequence of LPs from Secrets to Riptide, are perhaps those which run closest to the notion of a Compass Point sound, or at least a Compass Point ethos. But they are too idiosyncratic, too much their own thing. Palmer rarely featured All Stars players on his music, while Tom Tom Club were based around one of the very few rhythm sections – Chris Frantz and Tina Weymouth – that could rival Sly & Robbie for both distinctiveness and brilliance at that moment. When it comes to defining Compass Point, the Grace Jones albums are it.

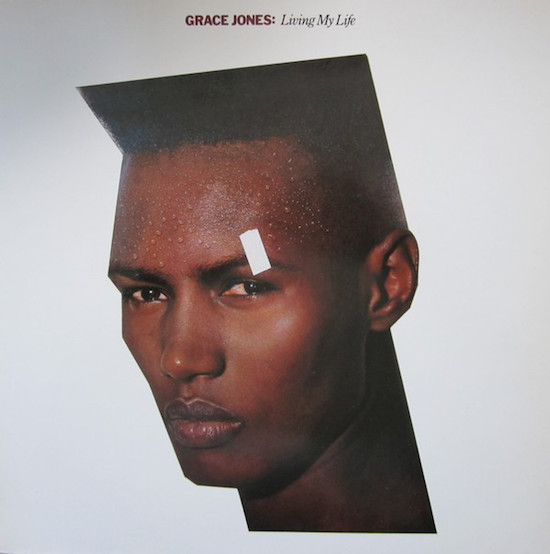

But, and here’s the important part, the Grace Jones albums are enough. They are that good. They are that great. There is nothing like them – nothing, at least, that worked anything like so well in anything close to the same form. As art and as artefacts, with the gleaming, ingeniously manipulated, hard-edged androgny of the image Jones developed with artist Jean-Paul Goude intrinsic to the way one felt and heard them, they were too complete and self-contained a triumph to accomplish the wider purpose Blackwell had in mind. They were too singular, sui generis, to sell the Compass Point sound to anyone who minded trailing in Jones’s wake. It arrived fully formed, and straight away it belonged wholly to her. Furthermore, it was only just recognisable as reggae at all. It was such a leap, not just from the gritty roots rockers, but from the psychedelic retro-futurism of the best dub (that sense you were listening to something both ancient and unimaginably advanced), into a sleek, internationalist new mode of pop, with the depth and space of reggae, the sharp corners and serrated kineticism of post-punk and new wave, and the enveloping, icy ambience of the coming wave of synth-pop.

This immaculate fusion of stylistic elements derived from an ideal mix of personnel, and here again Blackwell deserves great credit. Most crucial of all was Jones herself, transitioning from disco, in which she had been an outlier. A diva she certainly was, and is, but a disco diva, not so much; what she really needed, and got, was a genre to herself. Her best remembered number from her disco phase isn’t a disco tune at all. Her epic bossa nova take on Edith Piaf’s ‘La Vie en rose’, while it certainly shows that Jones could hit the notes dead-on when she wanted to, underlines how her spiritual (and soon to be stylistic) peers were not the technically gifted, octave-spanning female soul/R&B singers who dominated disco, but the tar-voiced queens of the European theatrical style: Marlene Dietrich, Nico – and, albeit inadvertently so, Marianne Faithfull, whom the hard years had turned from nightingale to crow. Faithfull had only recently signed to Island herself and recorded her masterpiece, Broken English – a further testament to the label’s seldom erring collective ear – and at that point she and Jones were perhaps one another’s nearest artistic, if not musical, relations; a kinship underlined by their sharing of a common collaborator, Barry Reynolds, who became lead guitarist and songwriting partner to both.

In assembling the All Stars, Blackwell has stated, he “wanted a new, progressive-sounding band, a Jamaican rhythm section with an edgy mid-range and a brilliant synth player. And I got what I wanted, fortunately.” The synth player was the dazzling Wally Badarou, from France; the rhythm section Sly & Robbie, of course; not so much augmented as both magnified and ornamented by guitarist Mikey Chung and percussionist Uziah “Sticky” Thompson, Jamaican veterans and discreet magicians both. Reynolds added a stinging, throttled ferocity. The alchemist who united all this was Alex Sadkin, a producer of uncanny sensitivity towards the artists he worked with, and a virtuoso on the mixing desk. Sadkin was to die in a road accident in 1987, and any remaining hopes that Compass Point might become a popular byword went with him.

In his sleevenote essay accompanying Private Life: The Compass Point Sessions, a 1998 anthology that chiefly features long versions and 12” mixes of the material from that period, Brian Chin writes that, “At the time, only Prince was achieving a similar synthesis,” and this is exactly right. What Prince was achieving with funk and R&B on Dirty Mind, Controversy and 1999 – new-waving them, fundamentally altering their DNA until they became something else altogether – Jones and the Compass Point All Stars did with reggae. Chin also cites Chrissie Hynde’s delight with Jones’s version of Hynde’s song ‘Private Life’. London punks, Hynde recalled, were obsessed with reggae and all wanted to play it. (Bennun’s First Law of Reggae, occasioned by the usually excruciating work of dabblers in the form, states that only people who play reggae all the time should play reggae at all; but rules are made to be broken, and foremost among the exemptions are The Clash and Elvis Costello.) The Pretenders’ version is pretty damn good. Jones’s is outstanding – “Now that’s how it’s supposed to sound!” said Hynde – and somehow more punk in spirit than the original. Another thing that should be noted of Jones is a quality she shares with Nina Simone and Johnny Cash: once she covers a song, it stays covered, and her version will rival or often eclipse the original.

Thus it was with Warm Leatherette, which was near as dammit a covers album, but about as far away from the usual premise of a covers album as it’s possible to get, so cohesive and jaw-droppingly original is it. Only two of its eight songs had not been previously recorded. Those are among its slighter numbers, although this record carries no passengers. ‘A Rolling Stone’ (co-written by Deniece Williams, who seldom puts a foot wrong anywhere) is a bouncy, reggaefied kissing cousin to Northern soul, albeit a cousin in wraparound shades and a leather trenchcoat. The rocky, Reynolds-authored ‘Bullshit’, heard now, seems to anticipate with curious similitude the sound Tina Turner would favour on her blockbuster comeback album, Private Dancer, four years later.

The covers are at the least bold and at best revelatory. ‘Warm Leatherette’ – the very first track the ensemble recorded, so it’s fitting it should open the album and set the stage – is so cool and eerie, so stabbing and juddering, so sleek and muscular, that next to it Daniel Miller’s minimal original feels like an ingenious but brittle model prototype for this full-scale, robust, finished item. Roxy Music’s ‘Love Is The Drug’ is a stone dance-pop classic (with, it should be said, reggae-esque inflections), but Jones’s titanic version gives nothing away to it, and one pictures her rolling across the dancefloor, an inexorable force, to seize her prey – a theme taken up by Smokey Robinson’s ‘The Hunter Gets Captured By The Game’, paced here by metronomic quasi-funk groove. On ‘Pars’, borrowed from Jacques Higelin and never returned, Jones effectively invents chanson-reggae, which as a summary of her style is too narrow but otherwise not unfair.

Jones’s Compass Point trilogy runs the way great trilogies tend to, whether in music, books, or film. The first part (Warm Leatherette) is a marvellous new thrill, the bold, attention-grabbing, turf-staking realisation of an idea. The second (Nightclubbing) both builds upon and surpasses the first: its creator(s), justly flushed with confidence in their artistry, their idiom and their judgement, bring the whole business to a magnificent peak. The third (Living My Life) is something of a falling off; they have said most of what there was to say, and now things become diffuse. Which is not to imply Living My Life is akin to The Godfather Part III. It’s no clunker, dragged along behind a pair of beautiful machines. Had it been released before, or without, the other two records, its reputation would surely stand much higher. Nightclubbing is such an astonishing LP, with not a track, not a moment, ever more than an inch away from perfection, that any follow-up was bound to fall under its shadow; yet Living My Life, with its mixture of experimentalism, ferocity and languour, and the All Stars playing with as much finesse as they ever did, remains an object of fascination. Nor should one read too much into the fact that alone of the trilogy, it comprises not just mostly but almost entirely original songs. Songwriting is not Jones’s primary strength, is all. It didn’t need to be. It wasn’t Nina Simone’s either (although both have written classics); and neither woman is any less of an artist for that.

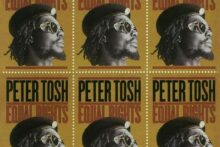

As for Compass Point itself, its legacy divides into two parts quite neatly. A list of the albums recorded there will tell you what a success it was in commercial terms – and often artistic ones; Black Uhuru’s run of Compass Point records, for instance, is a marvel. But so far as Blackwell’s vision of imprinting its identity upon pop history goes (and despite the claims sometimes made for Joe Cocker’s Sheffield Steel), Grace Jones is the sole meaningful exhibit – and the only one it requires.