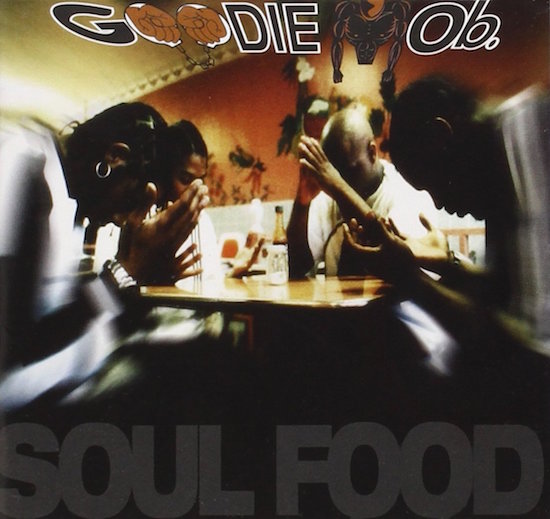

Influential albums aren’t always commercially successful, but often obscurity tempers their impact. In rock music, perhaps the most extreme example is the first Velvet Underground album, which probably caused more bands to form and release records than it sold copies. In hip hop history, its nearest equivalent may well be the debut by Atlanta four-piece Goodie Mob – a record that went gold, just about, but which gave a name, a direction and a focus to the genre’s third major phase of development.

By the mid-1990s, a collective of musicians, producers, rappers and singers had coalesced around an Atlanta studio nicknamed The Dungeon. The scene was rising fast, with its first album – OutKast’s Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik – broke the duopoly of hip-hop’s creative centres of gravity, New York and Los Angeles. The record was the work of two primary creative groupings – the OutKast duo of Andre 3000 and Big Boi, and Organized Noize, the producer team of Rico Wade, Ray Murray and Sleepy Brown. But other members of what was already being called the Dungeon Family were involved, too – including rappers T-Mo and Khujo, who were in a group called the Lumberjacks; another emcee called Big Gipp; and a rapper-singer three years their junior who went by the name of Cee-Lo.

It was apparently Wade’s idea that the four should join forces, and the decision was taken relatively late: they had not worked together before they began sessions for their debut LP. By that time, Cee-Lo had appeared on one of the biggest hit singles of the year – he supplied backing vocals on TLC’s ‘Waterfalls’, a record produced by Organized and co-written by Dungeon Family alumnus Marqueze Etheridge. The group’s name would be explained on the album as a partial acronym, with the song ‘Fighting’ saying it stands for "The Good Die Mostly Over Bullshit". The more prosaic explanation is that T-Mo and Khujo had taken to wearing small bags attached to their belts in which they carried weed, cash and other treats: they called them "goodie bags" and the name was brought over to the group they became half of.

The intentions behind Soul Food were clear. The record was to build on the Organized Noize template in a way that could complement and amplify the styles and moods of OutKast’s debut, but at the same time provide something individual enough to give the new Goodie Mob outfit an identity of their own. As Cee-Lo was to observe some years later, the intention the band had in its earliest days was both to establish themselves as a separate entity, distinct from the lengthening shadow of OutKast, but to do so through a sincere belief that they were making music that could connect and communicate even if it didn’t necessarily sell by the bucketload. No artist ever goes in to a project hoping for it to be unsuccessful, of course: but the metrics Goodie Mob were apparently using to assess the worth of their work had less to do with sales figures than the ability their music had to reach remote corners of as wide and unexpected a listenership as possible.

"I myself refuse to be written off as entourage of OutKast," Cee-Lo told me in 2010. "Goodie Mob had somethin’ completely different, equally different, and solid, but not in terms of sales. We did something different, music-wise, but we had another agenda, and we were equally effective and impactful with what our agenda was. It was never to make hit records, because I never thought about it in that way. What’s a hit record? I don’t know. Shit – I just don’t know. All the hit records that inspired me, I don’t necessarily think they were written with me in mind. Did Boy George know that ‘Karma Chameleon’ was gonna have an effect on me? I doubt it! But he didn’t count me out, and that I can appreciate. That’s how we looked at it."

The result was an album of spooked, sparse, spacious songs suffused with lyrics that run the gamut from prayerful incantations to tinfoil-hatted conspiracy theories, with everything from healthy eating, the prison industry and odes to their mums slotting in in between. But above them all, at least in terms of how the album has come to be regarded, there was the track that not only defined Goodie’s sound and style, but gave impetus to a regional scene.

‘Dirty South’ was a song before it was a movement, and it was an idea before it became a song. Stranger still than that it was the politicised and spiritual Goodie Mob who gave a name to a style that would become synonymous with strip clubs and on-the-grind raps, but the song’s concept, hook and most of the verses were the work of a Dungeon Family member who wasn’t even a part of the group. According to Wade, Cool Breeze had brought the idea to Gipp, who in turn encouraged Organized to work it up into a song. In the end, only Gipp from the group gets to perform a verse – there are two from Cool Breeze and one from Big Boi, while Cee-Lo ad libs during the choruses. The track achieves its considerable power through a daringly ruthless minimalism: a four-note bass line is augmented with a light, skittering programmed drum loop and every now and then an echoing keyboard line blows in and out. It feels delicate yet never insubstantial – as ephemeral as a mood, as indestructible as depression. The effect is a kind of haunting – music that you can feel creeping up and down your spine. Perhaps counter-intuitively, considering the fact that its title came to stand for a genre, the song isn’t about music at all: rather, the idea it symbolises clearly yet obliquely is that the southern states have their own manners, customs and practices which outsiders, as yet, know little or nothing about.

The hook imagines a raid by the Red Dogs, a police drug unit (the name apparently stood for Run Every Drug Dealer Out of Georgia), but Cool Breeze’s verses brilliantly interweave the south’s cocaine epidemic with contemporary politics and the history of slavery. (That he didn’t go on to do much more than release a couple of little-heard solo albums before changing his name to Freddie Calhoun, appearing on the Dungeon Family’s 2002 album Even In Darkness, and then pretty much vanishing, is bewildering given how great his contribution is to this genuinely iconic moment in rap history.) In his opening bars, he imagines how then president Bill Clinton would react were he to be stung for three kilos of coke by a dealer out to set him up; later, he wonders whether white America, which he personifies as a ’60s sitcom hillbilly, might look on the current crime rate – particularly on the then ongoing OJ Simpson murder trial – and decide that perhaps bringing blacks in chains to the new world wasn’t such a smart idea after all:

"See in third grade this is what you told:

You was bought, you was sold

Now they sayin’ Juice left some heads cracked

I betcha Jedd Clampett want his money back."

It’s followed on the album by another absolute spine-chiller of a track from Organized, and although an overall sense of difference and of being misunderstood by outsiders characterises both pieces, they are in all other respects like chalk and cheese. ‘Cell Therapy’ blends a nagging, unresolved piano riff with woodblock rasps and understated bass and drums. It seems related to OutKast’s ‘Ain’t No Thang’, in the way both are able to suggest urban jungles filled with unseen creatures of the night, calling to each other with hoots and cackles that could signal anything from ordinary business to imminent threat: both songs feel like the aural equivalents of expeditions deep into unexplored territory.

On ‘Cell Therapy’, though, the atmosphere of near-panic caused by a sense of incipient danger is emphasised by the lyrics, which rely heavily on the book Behold A Pale Horse, a confused and befuddling tract written by a radio broadcaster popular with the militia movement named William Cooper. Timothy McVeigh, who killed 168 people when he blew up the Alfred P Murragh building in Oklahoma City during the spring of 1995 when Goodie Mob would have been working on this record, was apparently an increasingly devoted listener to Cooper’s shortwave radio show: although not affiliated with any extremist group, McVeigh appears to fit the militia stereotype of viewing himself as the last line of defence for the American Constitution, a kind of ultra-patriot who saw the US government as complicit in a left-wing plot to create a global superstate which would deny US citizens key freedoms, such as the right to bear arms. Yet despite its obvious and perhaps intended appeal to the extreme right, Cooper’s book became a key text in many rappers’ lexicons – references to it crop up in records by everyone from Wu-Tang to Canibus and Nas (though when Talib Kweli cites it, he does so to question its value) – and Goodie Mob appear to have drunk deep from this poisoned well. While the group make for unlikely militia recruits, ‘Cell Therapy’s hook ("Who’s that lookin’ in my window?/Pow!/Nobody now") comes from exactly the same mindspace.

Cooper’s book intersperses lengthy and rambling rants against a shadowy New World Order with fragments of what purport to be official yet deliberately occluded documents – documents which have passed in to Cooper’s hands for reasons never made clear. ‘Cell Therapy’ cleaves to a similar structure, lines prophesying the suspension of the Constitution and allusory references to an organised race war sitting next to images of contemporary concentration camps, black helicopters and the horsemen of the apocalypse in a kind of unified field theory of conspiracist claptrap. But then, almost buried in the middle, there’s a verse from Cee-Lo that makes its (mostly) more sober points in a clear, level-headed and intelligent manner – and does so with sufficient poetic insight that it succeeds in eclipsing the majority of the other stuff that it’s hidden amongst.

"Me and my family moved in our apartment complex

A gate with the serial code was put up next

They claim that this community is so drug free

But it don’t look that way to me

‘Cos I can see the young bloods hanging out at the sto’

24/7 junkies looking for a hit of the blow

It’s powerful

Oh, you know what else they tryin’ to do?

Make a curfew especially for me and you

The traces of the new world order:

Time is gettin’ shorter

If we don’t get prepared, people, it’s gonna be a slaughter

My mind won’t allow me to not be curious

My folk don’t understand so they don’t take it serious

But every now and then, I wonder

If the gate was put up to keep crime out

Or to keep our ass in"

Soul Food is far from a two-trick pony, but ‘Dirty South’ and ‘Cell Therapy’ are by some distance the best tracks on it, and because they come early and in tandem in the running order (tracks four and five, respectively) they do tend to overshadow the rest of the record. The title track is great, and provides perhaps needed evidence that Goodie Mob could do light and uplifting as well as provocative and intense. ‘Guess Who’ finds each member eulogising their mother – a topic freighted with some difficulty for Cee-Lo as the album was made in the desperate period between his mother’s long-term hospitalisation following a car crash and her death some two years later. It would be of considerable comfort to the musician that his mum got to hear the record before she passed away.

"My sister went and took up nursing so they could be near and take care o’ my mother," Cee-Lo told me in 2010. "She told me that, once, that [his mother] said, ‘Play Carlo’s album.’ I had a few advance copies of Soul Food – this was before we even got a chance to pick the cover art or do the liner notes, and I was able to dedicate that album to my mom enough time before it went to press. She asked could she just hear it: ‘No, don’t fast-forward, just play it.’ I could look at the nature of that album and I could see where somethin’ like that could’ve said to her, ‘OK, he’ll be alright. He’s fine. He definitely got his head on straight’." The group’s subsequent history never really saw them scale the heights Soul Food shows they were more than capable of reaching. A follow-up sold poorly enough to provoke a rethink, and so the third LP, World Party, ditched the social commentary and spiritualism to promote something more upbeat and frothy. It didn’t fare any better.

Following the release of the Dungeon Family album, Even In Darkness, in 2002, Khujo fell asleep at the wheel driving home from the studio: he had to have part of his right leg amputated. With previously agreed solo projects emerging from Cee-Lo and Gipp, the group ended up communicating via the press: quotes from Gipp suggested he held Cee-Lo partially responsible for Khujo’s stress prior to the accident, while different members gave differing accounts as to whether the group was on hiatus or had split up. In his book about southern hip hop, Third Coast, Roni Sarig says label boss LA Reid claimed the group had asked to be released from their deal, though Khujo says he found out they had been dropped when he read about it in a magazine. Eventually, Gipp, Khujo and T-Mo put out a fourth Goodie Mob album without Cee-Lo: titling it One Monkey Don’t Stop No Show didn’t appear to suggest the most conciliatory of moods in the camp toward the erstwhile fourth member. Cee-Lo responded on his second solo album with what remains perhaps the greatest of all dis tracks: ‘Glockapella’ sees him verbalising his anguish as he feels compelled to fight back even though doing so, against friends he’d grown up with, is a cause of considerable regret. Yet the song would have an unexpected outcome: it helped get the band members talking. And after ‘Crazy’, the first single from his collaboration with Danger Mouse in the duo Gnarls Barkley, had put Cee-Lo on the mainstream pop radar, the quartet finally managed to bury their respective hatchets and, in 2013, released Age Against the Machine, the first album from the original line-up in 14 years.