The Feelies by Lynne Pickering

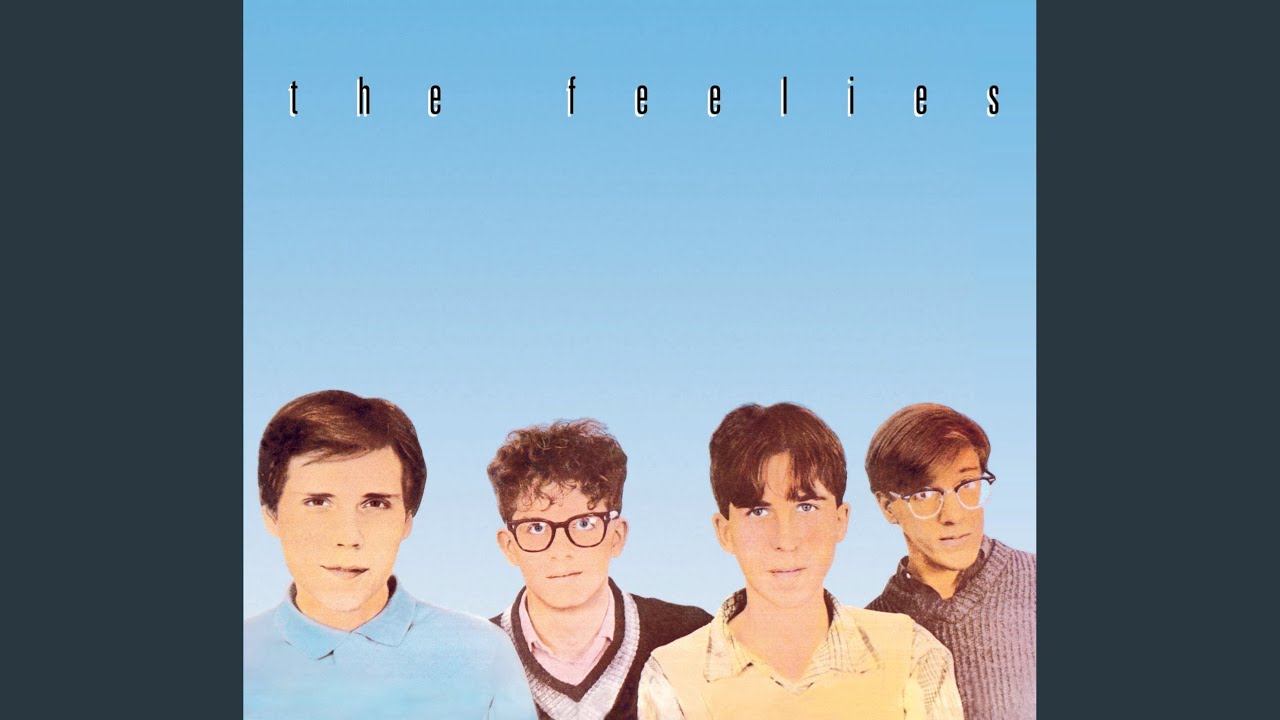

Taking their name from Brave New World by Aldous Huxley, The Feelies were formed in Haledon, New Jersey, in 1976. Hailed by The Village Voice in 1978 as “The best underground band in New York”, they underwent a number of line-up changes around core members Glenn Mercer and Bill Million as they finely tuned their sound, before finally releasing their debut album in 1980.

Crazy Rhythms is a true gem of American post punk and the first sally in an unhurried salvo of six essential releases from a band who hold a special place in many hearts. The Feelies influenced many other bands, including R.E.M., Yo La Tengo, Weezer and Real Estate, whilst Rolling Stone listed their debut at number 49 in their “100 best albums of the 80s” feature in November 1989.

Those who already know them will understand the loyalty they inspire. For the uninitiated, imagine a band that combines the twin guitar attack of Television, the hypnotic groove of Neu!, the uber-cool vocal delivery of Lou Reed, the repetition of Steve Reich and Philip Glass and the scorching, single-note guitar solos of Neil Young. Now imagine that during the course of the 40-plus years they have been together, that they’ve barely put a foot wrong in terms of album releases. Further yet, that they are still a potent live force to be reckoned with, who when they do (infrequently) choose to perform, tend towards three-hour sets crowned with a wide-ranging array of loud and raucous covers delivered in their own inimitable style.

In short, they are a much-loved American institution, a band with an unmistakable warmth of sound, which for those so attuned is like stepping back into warm spring sunlight, instantly familiar and welcome no matter how much time has elapsed since last it was felt.

Signing to London’s Stiff Records, The Feelies (not unlike Devo), had a strong sense of how they wanted their debut to sound, which involved producing the record themselves. Unorthodox though their fledgling methods were, the claustrophobic yet highly kinetic, minimalistic sound they created ensured an air of timelessness for their debut.

‘The Boy With The Perpetual Nervousness’ begins with a sparse tapping of wood on wood, like water dripping, like a code being lightly being rapped out. A droning swell of guitars subtly building, a heart-like drumbeat, a satisfyingly rough sound like a box of matches being shaken, or wood being rubbed against sandpaper. Mercer’s vocal is a perfect fit for the music. There is a kind of blankness to it, yet also a fragility and intensity: “There’s a kid I know but not too well/ He doesn’t have a lot to say/ Well, this boy lives right next door/ And he never has nothin’ to say.” Anton Fier’s rolling drums and additional percussion propel the track along, rumbling like the sound of a train reverberating through tunnel walls.

‘Fa Cé La’, with its English intonation by American musicians, illustrates the reciprocal nature of influences back and forth across the pond. The Feelies, by their own admission, were originally influenced by the British Invasion, yet their debut foreshadowed some of the music being made in the UK by at least two years. Orange Juice, Josef K, even the more frenetic sounds of the Fire Engines exhibit many similarities with Crazy Rhythms.

‘Loveless Love’ and ‘Original Love’ offer persuasions of a gentler, yet ultimately joyous kind. The former showcasing some great, single-minded soloing from Mercer at its beginning, before releasing a cascade of shimmering string strummed rhythms and rattling percussion towards its end. The latter is one of several high points on the album, anticipating in some ways the sound of a similarly emotive and jangly band who would experience much success in the UK some four years later. A cover of ‘Everybody’s Got Something To Hide (Except For Me And My Monkey), remakes the Beatles’ tune in The Feelies own hyper-kinetic image. A perhaps too subtly quiet intro to ‘Moscow Nights’, nevertheless pays off with a gorgeously euphoric ending. In contrast, ‘Raised Eyebrows’ begins in media res, only issuing its brief lyrical statement at the song’s very end. ‘Crazy Rhythms’ wraps the album up with an ecstatic extended passage of hypnotic drumming and droning guitar tones.

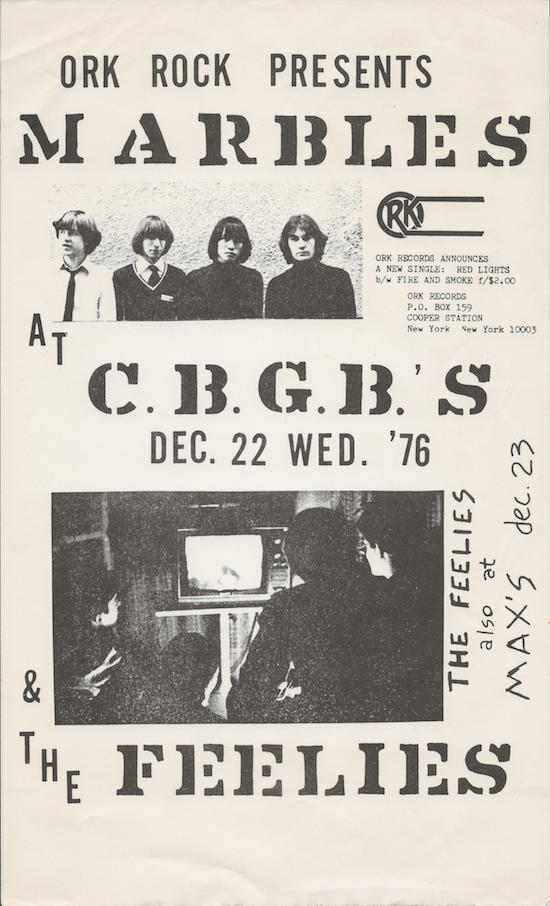

When tQ speaks to him, Bill Million is actually skeptical about the Feelies’ influence on other bands. “I don’t think Real Estate sound like The Feelies,” he says. “I certainly don’t think R.E.M. sound like The Feelies.” Perhaps this feeling also extends back to the point of their origin. Glenn Mercer recalls: “In New York at that time, there was an influx of bands from all over, with the press and the attention that the CBGBs scene was getting. Patti Smith had a record out, Television had a record out. They had a summer festival in CBGBs. It was something like a hundred bands, so to stand out, you really had to be unique. We spent a lot of time thinking about what we liked about bands and what we didn’t like. Even though it took a while to get a record out, it didn’t seem like a lot of time to us. Each time we would play, we’d want to be a little bit better and more unique. I think we were able to accomplish that.”

Million remembers: “Glenn and I shared a lot of the same ideas musically and they come at us without much discussion. I think that’s why we’ve been playing music together for so long. Both of us were big Beatles and Stones fans. Big Velvet Underground fans. Stooges, the MC5, Dylan, the Kinks. Preceding Crazy Rhythms, we started listening to more experimental music. Growing up in the New York area, there were the radio stations WBAI and WFMU. WBAI would play a lot of eclectic world music, like the ‘Balinese Monkey Chant’. Right around the time of the punk scene hitting, we had really lost interest in punk, because we’d heard it all before. We started listening to Brian Eno, Philip Glass, Steve Reich. I think you can hear some of those things on Crazy Rhythms – like the end of ‘Raised Eyebrows’. It has a Here Come The Warm Jets vibe to it and earlier in the song, and the snare rimshots are like a nod to Steve Reich.”

Jonathan Richman’s proto punk band, The Modern Lovers, were a touchstone too, as was their suburban environment, close to, but not directly a part of, the fertile New York scene. According to Mercer: “The Modern Lovers were a big influence. We saw them, New Year’s Eve 72. They were on a bill with the New York Dolls. They totally blew my mind. It was the image too. They came up at the tail end of the glam rock period, so to see them bookended with the New York Dolls, it was like they passed the torch. Punk was going in a predictable way and we just wanted to stand out. Also, I think where we come from, being from the suburbs comes through. When we put Crazy Rhythms out, people would ask: “Are you going to move to New York now?” And we were like: “No, we like where we are.”

Million adds: “We weren’t interested in the way the punk bands sounded, with this heavily overdriven sound. It just seemed to be very one dimensional. Even the Sex Pistols, what was a turn off for me, was that they were gaining more notoriety before they actually put out a piece of music, which I didn’t quite get.”

An early experience with a producer only served to reinforce the notion that they needed to shape the record themselves. “We knew exactly what we wanted,” says Mercer. “We had recorded with a guy for a tentative release on Ork Records. When we were done recording, the producer said: “You guys go take a dinner break and I’ll do a rough mix.” We came back and we just said: “No, we really need to do this ourselves.” At one point we had talked to Philip Glass about producing. I think it was RCA records who suggested him. We had a meeting. Recalling that meeting, Million adds: “Philip Glass as I understand it, actually worked for years as a plumber, and his hands looked like a plumber’s hands. He was sitting across from Glenn and I at the table when we were met with him to discuss Crazy Rhythms and I just couldn’t take my eyes off his hands, these massive fingers. It was an absolute thrill to sit across from him and meet him, having listened to his music.”

The deal with Philip Glass went to another New York band strongly influenced by minimalism, Polyrock, whose Glass-produced eponymous debut, was released by RCA, also in 1980. That album is another under appreciated post punk classic, which shares some common territory with early Feelies work, and comes highly recommended. Polyrock released a still largely excellent second album in 1981, but by 1982s Above The Fruited Plane EP, their sound was almost unrecognisable from their debut.

The Feelies, however, stuck to their own ideas as they have done throughout their career, all the way up their most recent record, 2017s beautiful In Between. Former CBGB soundman, Mark Abel, who worked with the band on Crazy Rhythms at New York’s Vanguard Studios, famously called them “the most obstinate people I’ve ever met”.

Million recalls: “We really used our inexperience to our advantage. We wanted to produce the record ourselves, as we felt that was kind of part and parcel to the song writing. Stiff Records allowed us to do that. As we didn’t have a lot of experience in the studio, a lot of it was discovering sounds, turning dials and and just laughing about a lot of what we were coming up with. We made use of what was in the building. The studio was cavernous. It had really high ceilings and was designed for orchestras. We discovered these sounds in hallways and cubby holes and alcoves and made a lot of use of that. It had a lot of natural reverb. It also had a great reverb plate. In ‘The Boy With Perpetual Nervousness’, there are these sandpaper parts that I played. It’s just reverb pushed to almost maximum level. The same with the temple blocks in ‘Crazy Rhythms’. It almost sounds like a car coming to a screeching halt, but it’s temple blocks.”

“We had issues with the recording of the guitars,” Mercer recalls. “They just weren’t sounding right. Our co-producer wanted us to double track. We wanted it to be as live as possible. There’s a spot on the Modern Lovers record where you could actually almost hear him clicking on the fuzz box. It’s so cool, that’s the effect we wanted. We tried and tried and we couldn’t get a real good sound, so we wound up at the very last, running out of time at the studio. The engineer said: “We only have a few days left until we have to leave, why don’t we just record direct to tape and then we’ll feed them back into the amp when we go to mix.” We did that as a kind of drastic measure and we wound up actually liking that sound. A lot of the guitars, particularly my guitars, the rhythm parts and the picking parts, that’s all direct. The one thing they always say, is don’t record direct because all the flaws come way out, but what I like about it is it actually puts it closer to your ear.

“Another thing was the long break in the middle of Crazy Rhythms. We said to Anton, I’ll count the measures out and when we get to sixth or eighth, then we’ll come back into the verse. I kept counting, he couldn’t hear me and then somehow we were finally able to get back on track, but we had too much time in the middle. We didn’t know about tape editing back then, so we just decided to fill up that space with all those percussion parts. They were difficult mixes, because there were a lot of subtle things going on. Sometimes we’d find that we’d get three-quarters of the way through the song and make a mistake. We’d be like: “We’ve got to start all over again.” The engineer said: “No, you can just pick up where you left off and I’ll splice the tape together.” I remember when he actually sliced the tape with a razor blade, we just had this look of fear on our faces, thinking he was going to ruin it, but he put it together and we couldn’t believe it. We should have known about that a lot sooner, it would have saved a lot of time. We wound up mixing little segments, rather than from beginning to end and then assemble all the segments.”

Crazy Rhythms was the only Feelies album recorded with Anton Fier as drummer. Fier, who went on to found the Golden Palominos, was also an early member of John and Evan Lurie’s Lounge Lizards, the Lodge, with Henry Cow’s John Greaves, and collaborator with Pere Ubu and Bill Laswell. Fier’s hypnotic drumming brings a slightly different quality with it than subsequent Feelies albums, but both Mercer and Million are dismissive of the notion that he set the tone for the later lineup’s use of a drummer and additional percussionist.

Million recalls: “Anton, when we played live, a lot of times he’d get sick because the tempos of the band live were considerably faster than what they ended up being on that recording. Where the drummer and percussionist set up came from, was really out of necessity. We went through a period where both Glenn and I were both playing Fender Stratocasters and we found that a lot of the guitar parts were being cancelled out by the drummer playing cymbals. So we started experimenting with taking the cymbals out of the music and replacing that sound by adding various bits of percussion.” Mercer adds: “We actually had two drummers prior to Crazy Rhythms. At first, we had a kind of revolving door with different people coming in and playing. Then we decided the parts were getting more and more challenging, so we decided to get Dave [Weckerman] to come back, because he was originally the drummer. Since we wrote all the percussion parts, we thought we didn’t need to have him there. We were expecting Anton to play them. But after he did the basic tracks, he was like: “I’ll see you guys in a couple of weeks.” So Bill and I wound up playing all the percussion.”

The record wasn’t perhaps what Stiff had been expecting and their relationship with the label faltered after the demo for a follow up album was rejected. Fier and Keith DeNunzio left the band, while Mercer and Million played in a duo as The Willies and in a number of groups with other local musicians, including the Trypes and Yung Wu. Eventually reforming as a quintet with Stan Demeski on drums, Dave Weckerman on percussion and Brenda Sauter on bass, The Feelies recorded The Good Earth in 1985, with Peter Buck of R.E.M co-producing, along with Mercer and Million. The record had a softer, more pastoral sound than its predecessor, but the band’s commitment to their own particular brand of minimalism remained strong.

Like the best of the Feelies post-Crazy Rhythms albums, The Good Earth’s songs emit a gorgeous, warm resonance, not unlike the ‘Golden Sound’ that maverick minimalist, Charlemagne Palestine, sought to express in his own compositions. Whilst being compared to The Velvet Underground is an occupational hazard for many guitar bands of a certain stripe, the comparison rings truer for The Feelies than it does for most. Any similarities between the two are largely limited to vocal delivery and the use of the drone however, with one essential difference – The Feelies use the force of the drone for good, rather than as an expression of the darker aspects of the human experience; even though there is still a touch of the melancholy to their sound.

When the album was released in 1986, they toured in support of it, opening for both Lou Reed and R.E.M. Also that year, the band appeared in the Jonathan Demme film, Something Wild, playing the part of a band at a high-school reunion. When Rolling Stone featured Crazy Rhythms in their list of best 80s albums in 89, their debut “took on a life of its own”, according to Mercer, who adds: “After that we would hear from other bands about how much that record meant to them.”

The Feelies back catalogue is one of the most consistent in popular music. If I were forced to choose one album, I might opt for The Good Earth, but there are wonderful songs across their entire catalogue, including their most recent, In Between. Mercer and Million are not easily drawn upon how they view their own back catalogue, however. “Pretty much the only time I’ll listen to the records is when I’ll go back to learn songs,” Million says. “Recently we were asked to do shows in New Jersey. We were asked to do Crazy Rhythms and The Good Earth, in their entirety. There were songs from both albums that we hadn’t done in quite a while. There were two songs on The Good Earth which I don’t think we ever did, so I had to go back and listen to those, but typically we listen to those albums enough when we’re making them. A lot of our music takes a long time. It’s not because we’re being super meticulous. It’s just the way we work.”

The Feelies then and now by Gunyup-Winter and Jerry Flach

Taking their time and doing things their own way, clearly remains as important as ever. There’s a sense that The Feelies exist almost in their own hermetically sealed world and to have never released a lacklustre record is very unusual for a band who have been going (even on and off) for over four decades. For a band who have been around as long as that to release an album as good as 2017s In Between, is unusual indeed. Million explains: “With In Between when we started doing the demos, both Glenn and I really liked the way the songs felt. A lot of times when we start putting together music, I may record something at home in my guitar room. These particular songs, I play a Gibson 335 (acoustic electric) guitar and I put a condenser mike up close to the strings, maybe six inches away and then plug into an amplifier five feet away. The amplifier gives ambient background sound, whereas the condenser mike picks up the sound of the strings. It’s a really clean sound. Glenn mentioned that it was a process that Norman Petty used with Buddy Holly’s guitar. Then when we got to recording In Between, I couldn’t duplicate that at all, so we ended up using the guitar tracks that I created at home and the unique thing about it is that the band played along with those tracks.

“There are a number of lessons that we’ve learned along the way. We realised that there were certain aspects of living inside the world of the music business that really was not a good fit for the band. One of them was touring. The other one was being compelled to work on a deadline. That was one of the things that came to the fore with The Good Earth. We had struck up a relationship with the owner of a venue in Hoboken, called Maxwell’s and the person who owned it went on to become our manager. We rehearsed there. We just went from a bad business experience to a greatly improved one and even to this day, the label that we work with, Bar None, lets us control our own schedule. We really only play a handful of times a year, so I think it keeps it fresh for the band. It has more significance, more meaning to the band itself and I think that projects out into the audience when we’re playing.”

When I began writing this article, it had been my intention for my wife and I to fly out to New York later in the year to finally see the Feelies play, as they were one of the few bands I really love that I had never seen live. Despite early news of the coronavirus coming from China, the notion of the kind of global lockdown and fatalities that we’re currently seeing wasn’t something anyone might have considered. No one knows how long this state of uncertainty might last, but I would like to take this opportunity to thank all the musicians whose work has contributed so much to our collective happiness and to wish them all a safe passage through these difficult times.