Call it ‘sludge’ if you have to. EYEHATEGOD prefer ‘southern hardcore blues’, wrenched from the bayou of New Orleans: progeny of punk and doom. ‘Lack Of Almost Everything’ from their third album Dopesick, if not quite a badge of honour, tells you all you need about their resignation and bitter humour. Philip Anselmo (ex-Pantera frontman disgraced at the outset of 2016 for throwing a Nazi salute and screaming "White Power" at the end of a tribute gig for murdered bandmate Dimebag Darrell) supplied an endorsement for the 2006 reissues of their back catalogue: "These Eyehategod records optimize the beautiful filth and ignorance of New Orleans. Primitive and infectious, EHG is punk rock in slow motion. A wasted, fuck you to the music scene. Bringing a much needed REAL threat to music worldwide."

A decade earlier, after a Pantera show on 13th July at the Coca-Cola Starplex in Dallas, Texas, Anselmo talked of how he "injected a lethal dose of Heroin into my arm, and died for 4 to 5 minutes. There was no light, no beautiful music, just nothing." Pantera were co-headlining with White Zombie and being supported that night by EHG. It was rumoured that when he overdosed Anselmo was listening to the self-titled debut by a new British band called Iron Monkey. Formed in Nottingham, the spirit and sonic ferocity of Iron Monkey immediately drew comparisons to EHG, though their sound – mainly down to their shrieking Nero of a vocalist Johnny Morrow – was even more direct and brutal. EHG and Iron Monkey were mad, bad and dangerous to know.

The year was 1996. This is the year EYEHATEGOD and Iron Monkey battled to be the heaviest band in the world.

To be ‘heavy’ is to be ‘of great weight’. What gives force, depth and weight to the music of EHG and Iron Monkey is undoubtedly the overdriven amps, the guitars tuned down to C# or B (in the case of Iron Monkey), the cut-to-ribbons drumming style and the prison-torture vocals. Moreover they understood in the middle of the 90s, as Julian Cope subsequently put it when talking about Khanate, that "Slow is the new Loud".

Heaviness is about struggle, and these bands struggled: struggled with addictions and bad fortune; struggled to make ends meet and leave their mark. In both cases, a now indelible mark. Heaviness is about a deep and troubling emotional resonance, even if their lyrics and song titles are oblique, or simply oh-so-bleak.

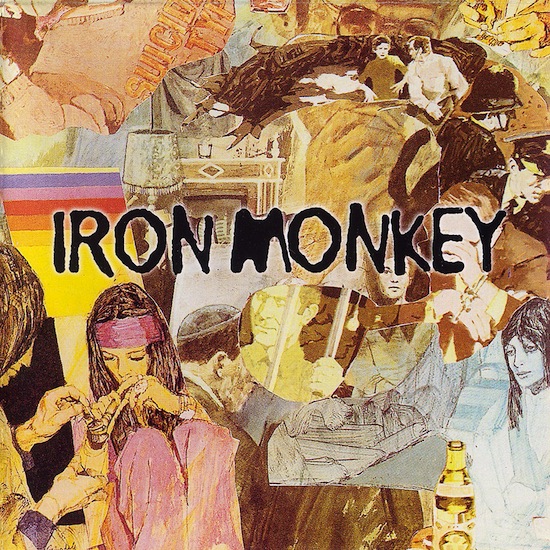

Both bands were this heavy because they came through in the middle of the decade that mirrored the 70s, that heaviest of decades. Discussing his latest film High-Rise in a recent interview with Mark Kermode, director Ben Wheatley said, "There’s that thing that you’re always either in the 70s or in the 80s. Right now, we’re in the 70s again: recession, terrorism, ecological collapse. And then the 80s is cocaine and arrogance and money; everything’s on the up, everything’s brilliant and it’s never going to crash again. And then it’s the 70s again!" EHG and Iron Monkey are 70s bands caught up in 1996 – the washed-out collage of Iron Monkey’s album cover evokes the decade: hippies injecting and smoking it up, a freeze-frame scuffle, a wraith-like addict, and police bobbies, who just have to be corrupt, leading a cuffed man away.

A huge element of both bands’ sound was forged in the furnace of early 70s proto-metal: Black Sabbath of course, but also all the bands that practiced atomic blues in 1970-1973. Obscurities such as Sir Lord Baltimore, Captain Beyond, Trapeze and Bang!, and the template laid down for heavy sounds and mental distress in the Groundhogs’ Split album from 1971.

If in essence they recall the 70s, their sonic force was filtered through the way punk and hardcore transformed in the 80s. They tuned as low as Napalm Death, abided by the simplicity and rage of Void, Negative Approach and Siege, and slowed it all down in the way Black Flag showed on the second side of their My War album and Saint Vitus throughout their self-titled debut. Two bands took this into the early nineties: Floor, who innovated plunging downtempo, and the Melvins. When the Melvins played New Orleans it introduced an approach to all the musicians who attended who didn’t already have Gluey Porch Treatments (1987) cassettes getting worn out, and calcified it in those who did.

Dale Crover’s drumming power in particular: Iron Monkey’s drummer Justin Greaves holds him up as an influence for the fact that in a dawning age of drum triggers and drumskin ticklers, he really beat the shit out of the drums. EHG drummer Joey LaCaze would play gigs around the release of Dopesick with no crash cymbals, compensating by hitting the ride cymbal as hard as he possibly could. After LaCaze died in 2013, Crover sat in for EHG’s comeback show at Anselmo’s Housecore Horror film festival. The Melvins are a band with as many variations on their musical style as line-up formulations, more diverse than the earth-shuddering sound they are taken to represent. But it’s the slow-mo-landslide Melvins of Bullhead (1991) and Lysol (1992) that is canonical here.

The soundbed of Dopesick is tinnitus. The high-pitched whine of the amplifiers out of which their complex and shape-shifting assault emerges. It gives the album a cloying, claustrophobic feel: stuck in their heads, stuck in your head – whichever is worse. The album begins with ‘My Name Is God (I Hate You)’: distorted screams and broken glass, which singer Mike IX Williams has insisted was authentic, the band graffiting the studio in Williams’ blood from a deep cut in his hand, inscribing Charles Manson crime scene slogans like ‘Death to Pigs’.

The bassline takes shape out of the murk before the whole band launch in. A classic blues formulation, they hammer the root note home, hit the major third emphatically, before sliding up to the perfect fifth and hooking back onto the diminished fifth, the tritone which imparts all of doom’s dread and sinister feel. That opening riff uses the same four notes as the opening of ‘Fink Dial’, the first track on Iron Monkey.

‘Fink Dial’ is different: it is punchier, launching onto the major third and using the semitonal alternation between perfect and diminished fifth to give the tail of the riff accent and emphasis, whereas EHG hang off it for dear life. Both songs’ openings speak an undeniable truth for slow metal: take Black Sabbath’s ‘Into The Void’, use its blues climb opening and re-order and subtract notes as necessary for maximum effect.

However, it’s not that simple. EHG’s songwriting is hallucinatory and woozy, leaving an overall impression of massive, swingtime passages, and chordal progressions that twist and turn in search of a never-reached resolution. Dopesick is an album the listener has to sweat out.

When you think you might be able to characterize ‘Masters of Legalized Confusion’ as straightforwardly soporific it takes things to an ecstatic peak. Then ‘Ruptured Heart Theory’ with its squalls of feedback, painful, palm-muted downstrokes and long drawn-out structure feels completely bereft. Guitarists Jimmy Bower and Brian Patton tease it out to excruciating lengths before recovering some semblance of melodic momentum, but the underlying message is that anything you care about conventional song structure you can leave at the door.

The album has mere sketches of songs, with ‘Dogs Holy Life’ and ‘Non Conductive Negative Reasoning’ barely making it over the one minute mark, but elsewhere EHG really defined their sound. Although many (including most of the band) regard previous album Take As Needed For Pain as their best work, Dopesick is more challenging, more abrasive, more dislocated and its moments of brilliance shine through like a black sun rising. ‘Lack Of Almost Everything’’s fiery opening bows out to an ignominious swamp-pit slowdown but then rises out with a catchy-as-all-hell groove that cements its place in their live set to this day.

Billy Anderson’s production washes everything in distortion, cymbals, any possible noise that belies the fact that EHG’s raw, hardcore blues satisfies on a base level unlike many other bands, and even if it’s uncomfortable listening they still know when to drop in a primal head-nodding riff or shake things up with a hardcore sped-up killing spree.

Let’s begin with Iron Monkey at the end. ‘Shrimp Fist’, like ‘Anxiety Hangover’ which closes Dopesick, begins agonisingly slow – each note fretted and bent out of shape wrung for all its worth. The track is a series of movements, riffs threaded together, some returned to, others discarded. Then it hits a drawn-out fuzz bass-driven finale, which limps over the line in a morass of feedback.

What precedes that is more direct and less sickly than Dopesick. The sticker Earache put on their 1997 reissue of the album encapsulates it nicely: "Nearly 40 mins of downtuned aggro-stoner sludgecore". The band puts emphasis on the aggro. ‘Big Loader’ comes out gorilla-swinging in almost triumphant fashion, then launches into a jump-up earthshaking refrain and girds it together in a wandering mid-tempo set-piece. ‘Black Aspirin’ is more schizophrenic: at first a meat-and-potatoes banger, then a clipped tunnelling section, a strange chromatic interlude, slowed-down black metal transitions and then gut-wrenching rolling and tumbling, to a squealing finale. Their madman-in-a-pub-fight aggression and unhinged, bad-acid vibe marked them out as contenders for coronation as the new heaviest thing going.

It helped Iron Monkey that there was a persistent rumour that they’d actually formed in prison. When they emerged, scenesters wanted to know what this band with baseball caps and skate clothes were all about. Justin Greaves was the only member of the band with long hair, the rest were skinheads or close-cropped, in baggy clothes and rucksacks.

This was a confusing time for heavy music aesthetically: look at the braided beard EHG’s Brian Patton wears in this recording of an outdoor show in Kansas City in August 1996. Stagewear had become much more streetwise, or simply much more like its audience. You can see Anselmo, wearing a shirt emblazoned with Charles Manson’s eyes, nodding along at the sidelines only a few weeks after his overdose.

Iron Monkey played their first gig at the Narrowboat venue on January 5, 1995, without any demo tapes or recordings to their name. Singer Johnny Morrow turned up for the gig late from work, having had no sound check. He ran in, went on stage, with his backpack and jacket zipped up to his chin, and just started screaming bloody gore. After they’d finished he chucked the mic down and left the building.

People either loved it or hated it, but they couldn’t stop talking about it, and the sheer genius of it was Morrow’s vocals. Morrow wasn’t vocalising in a punk or hardcore style, he was more extreme than that, screaming and gargling in a totally deranged manner. The band’s approach to lyrics was just to sit down and write words, a line each; the vocals not so much another instrument as an IED ripping through you. It contrasts markedly from Mike IX Williams’ rasping, shouting style. But EHG can take credit for this Burroughs-like lyrical approach, though Williams preferred to work in isolation.

The lyrics to ‘666 Pack’ read like the tracklisting of a great unrecorded EHG album, and make as much sense. If you can decipher them they serve to lacerate the mind with shards of imagery, invective or raw emotion. But really they are nonsense in the most nihilistic vein:

"Like taking candy from a graveyard

pro bandage curfew

thermal piss eyes/threat/function

autonomic click buzz fumes

prosthetic tooth + jaw to non

arm of paranoid narco virus

chief judicial of invisible empire

exile at wars end of slave booze pain

all it is is taking some pills to increase a shot

syringe hit scum king

two thieves a fucking mock survivor

hypno watt seepage thru hard drunken sores

fink pig illness tractor

face press revelation

garbage front stalwart

a psychotic plea from a dirty prison

world in bottle mid-fight transmitter

prozac frozen in ultra deep storage.

Man made object of cultish reverence.

During the first year of Iron Monkey playing live, things often escalated out of hand. And quickly. At many of their gigs it felt like anything goes, and the band were often on a knife edge between aggression and going completely berserk.

Morrow was often the focal point. Welsh fans recall that he played a gig hanging upside down from the exposed pipes attached to the ceiling of a pub basement in Swansea and how the microphone went repeatedly flying to the back of the room. Another time in Bristol, when

Morrow was tripping on acid, he picked up the support band’s cymbals and started throwing them at the audience as if they were frisbees. He walked up to one man in the crowd during the gig and put the live mic in his pint, and promptly walked out. The venue stopped putting shows on after that. In another incident, Morrow jumped on someone at the Underworld venue in Camden and broke his leg, only for the injured audience member to attend another gig a few weeks later to ask Morrow to sign his cast.

Mike IX Williams was no shrinking violet either, as the man who wrote a book called Cancer As A Social Activity: Affirmations Of World’s End (2004). But to talk up overt rivalry of the bands would overlook the essential comradeship between them. Jimmy Bower in particular would laugh it off with them whenever he visited the UK. Whether it was Bower who supplied Anselmo the copy of Iron Monkey that was playing when he died for that five minutes, we can but speculate.

Who wins the battle of these two heavyweights? If anything, their ‘victories’ are Pyrrhic. What weighs on their respective legacies is the tragedies that would subsequently befall them.

Iron Monkey hated their label Earache so much they gave an ultimatum to be dropped or break up. On September 11, 1999 they issued this statement: "Iron Monkey have split up. You don’t need to know the reason why. It’s none of your fucking business. Get over it." In June 2002 Morrow died when he hooked up to his kidney dialysis machine and suffered a heart attack, a result of rising blood pressure, and something that could have been prevented. A long-time asthma sufferer, EHG lost Joey LaCaze in August 2013 to respiratory failure. The other tragedy to hit them was Hurricane Katrina in 2005: a series of unfortunate events, including his house burning down and being arrested for drug possession, landed Williams in prison, adding cruel irony to Dopesick’s ‘Broken Down But Not Locked Up’. However, it rallied the underground around them to record a charity tribute album called For The Sick. Anselmo bailed him out and looked after him for many years after.

EYEHATEGOD have survived though, releasing their first album in fourteen years in 2014 and perhaps it is a fitting tribute that the producers of Treme – a show about New Orleans recovering itself post-Katrina through its culture and music – elected to feature them in an episode, in one of the most unrealistic depictions of a metal show on film. But it says something too, that the band had marked their tenth anniversary with an album called 10 Years Of Abuse (And Still Broke). The name of Iron Monkey’s posthumous rarities collection is more blunt: Ruined By Idiots.