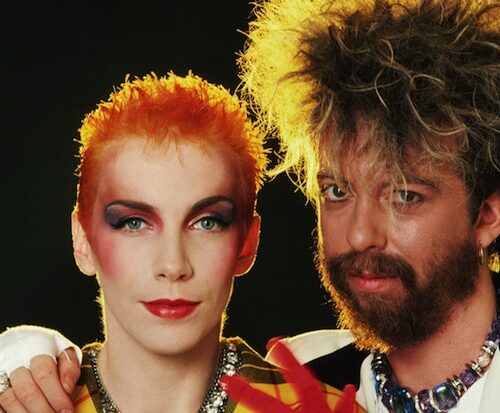

Released in 1983, Sweet Dreams was the album that finally gave Annie Lennox & Dave Stewart hits. The same year’s number one, Touch made them household names. Success did not come easy. The pair met in a London restaurant where Lennox, Academy of Music dropout (she quit 3 days before her finals) from Aberdeen, was waitressing. Stewart had been signed to Elton John’s Rocket label as part of Longdancer, way back in 1969. He proposed marriage on the spot and they became lovers. Their relationship fizzled out but a musical partnership endured. In The Tourists, they supported Roxy Music & enjoyed a one-off hit with Dusty Springfield’s ‘I Only Want to Be With You’. When that group disbanded, they formed Eurythmics.

It was the perfect moniker. By definition, Eurythmics means ‘the system of movement used to teach musical understanding for therapeutic purposes’ but for the band it would neatly encapsulate their modus operandi. In Stewart’s words they would conjure ‘a European emptiness but with soul in it’. Around the nucleus of the duo a whole cast of euro-centric players revolved, making them, less like other synth duos of the day and more like an electro Steely Dan ; outsiders with muso chops.

They didn’t arrive fully formed. Co-produced by Conny Plank, 1981’s, In The Garden, failed to dent the charts. Featuring such luminaries as Blondie’s Clem Burke, Can’s Holger Czukay & Jaki Liebezeit, DAF’s Robert Korl & even Stockhausen’s son, it sounds more like a dress rehearsal than a debut album proper. Their next album, Sweet Dreams would be the fulfilment of their namesake & the real curtain raiser to their musical vision. One collapsed lung (Dave) and at least one nervous breakdown (Annie) later, Eurythmics hit pay-dirt.

Acquiring a bank loan, they began self-financing recordings at a tiny 8-track studio above a factory in Chalk Farm, later moving to a Crouch End facility that became Dave Stewart’s own studio, the Church. There were, once again, helping hands. Robert Crash and ex-Selecter bassist, Adam Williams co-produced with Stewart. Dick Cuthell, go-to session man for everyone from Madness to XTC, supplied real trumpet, a nod to their R&B/Tamla influences.

But it was technology that would prove the key ingredient to Dave and Annie arriving at a winning formula. Armed with analogue synths like the Oberheim OB-X and EDP’s Wasp, they favoured meaty, big and bouncy electronics. ‘Johnny come latelys’ to the synth pop boom, their early records have nonetheless aged surprisingly well. This was music that embodied the best of its age: high-gloss, (relatively) low budget. They were all sharp edges, ‘razor-blade smiles’ to quote Touch’s Regrets and stiletto heeled, lip-gloss chic. The DIY ethics of punk applied to the pursuit of hit-making.

Throughout 1982 they issued a series of singles, the A-sides of which all featured on Sweet Dreams. ‘This Is The House’, ‘The Walk’ & first-time flop ‘Love Is A Stranger’ were at turns experimental, dramatic and full of hooks. ‘This Is The House’ combined slap- bass n’ horns funk with sounds similar to the Jupiter 8 arpeggios on Duran Duran’s ‘Hungry Like The Wolf’. ‘The Walk’ wrapped Numanoid glacial synthetics around noirish psychodrama (heightened by Dick Cuthell’s frazzled free jazz trumpet).

‘The Walk’ is their first bona-fide masterpiece, gusts of wind and Mike Garson-style, cracked glass piano haunt a mix where half the overdubs ‘drop out’, dub-like in the second chorus. It’s a rogue master-stroke, so lacking in today’s airless chart formulas. While recording the album, the band issued themselves with manifesto-like instructions, placing Kraftwerk next to Motown. The electro/ R & B fusion combined sensuality with sterility, full of tension. Chilly numbness co-exists with the ache of desire. ‘The Walk’s beautiful confidante is caressed in the verse and then dismissed by the chorus.

Flipsides from these singles, ‘Monkey Monkey’, ‘Invisible Hands’ and ‘Step On the Beast’ (the last two bizarrely omitted from Sweet Dreams’ 2005 remaster), reveal a questing spirit. Here they are more akin to the left-field electronica of Arthur Russell, the barmy ’81 singles of The Associates or even Suicide. The avant-funk of ‘Step On The Beast’ lifts the synth bass straight from Change’s Luther Vandross-assisted 1980 classic, ‘Searching’ but here it propels a more warped song. For further evidence, see their off kilter reimagining of Lou Reed’s ‘Satellite of Love’ (they were in the process of doing the same to ‘You Can’t Hurry Love’ too but Phil Collins got there first).On these records, lyrics are hypnotically intoned like dream-snatched chants.

When Sweet Dreams itself appeared, it curbed slightly these outré leanings, surrendering them to svelte pop values. Nevertheless, the album contained an ambience which equalled the forward-thinking, dub-heavy productions coming out of Nassau Point Studios such as ‘Don’t Stop The Music’ & Cristina’s oddball master-class ‘You Rented A Space’ (‘Your heart is as hard as a diamond’). ‘Somebody Told Me’ even featured a demented breakdown, predictive of Hot Chip. From the pangs of 60’s girl groups to art-damaged reggae, Eurythmics absorbed influences a-plenty into their machine made music.

If one figure was the guiding hand of early 80’s, it was David Bowie. It was a period of music-making & imagery, both shamelessly referential and original (itself, of course, a Bowie trait).In fact, the decade’s move from glacial synth-heavy pop to blue-eyed plastic soul seems like a mass enactment of his career trajectory backwards, from Low to Young Americans. Records like Dare and Non-Stop Erotic Cabaret had been eclipsed by the ‘MGM Philly’ of Trevor Horn-produced ABC album The Lexicon of Love. Even The League’s Phil Oakey noted that synth-only pop was becoming passé.

1983, the year Eurythmics hit the big time, was also the year of Culture Club’s Colour by Numbers and Bowie’s own Let’s Dance; warm-blooded and slick. With their chilly soundscapes and percolating brass, Lennox & Stewart folded the two styles in on each other with a series of hybrids. Like the similarly male/female Yazoo (‘Nobody’s Diary’ could have come from the pen of Lennox/Stewart), Eurythmics combined synthetic surfaces with testifying vocals. Sweet Dreams even included a frenetic cover of Sam & Dave’s Isaac Hayes co-write ‘Wrap It Up’, featuring post-punk Marxist turned pop believer, Green Gartside of Scritti Politti.

An eventual hit when reissued, ‘Love Is A Stranger’ took the breezy sensuality of Donna Summer’s I Feel Love into darker terrain. Instead of ‘falling free’, the narrator speaks of desire as obsessive, draining and as potentially dangerous as hitch-hiking. Even the title casts a shadow on old chestnut, Love Is Strange. But the thrill is still there, courtesy of a nagging, insistent hook and the cascading sounds of the Suzuki Omnichord, a kind of synth autoharp.

Throughout these records, Lennox’s delivery is cool, very much the pristine, ‘don’t fuck with me fellas’ poise of Chrissie Hynde/Grace Jones circa ‘Private Life’. The booming lower-register authority of Jones is certainly here, but so is operatic anguish. The almost schizoid vocal personae are a less daunting analogue to the shrieks & caresses Kate Bush used to such great effect on 82’s The Dreaming.

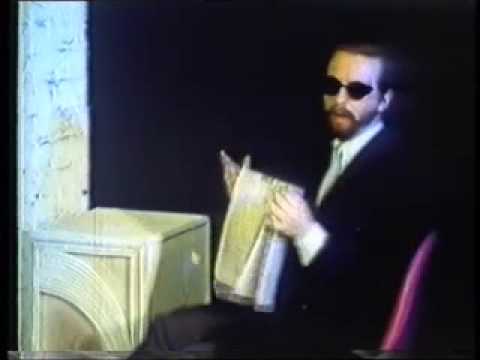

Equally jarring was the visual identities Lennox created in the band’s videos. 79’s Boys Keep Swinging saw Bowie parodying both male and female gender roles (the song’s ‘Boys own’ fantasy of masculinity juxtaposed with the female drag ‘archetypes). It was the final real flourish to a decade of gender-bending. Lennox picked up the baton. In the ‘Love Is A Stranger’ promo, the visual language is borrowed from Bowie’s own ransacking of the transvestite underground (the removal of the wig is also in Bowie’s Boys video, itself a debt to performer Romy Haag). Lennox alternates between high class female prostitute & male gangster garb (part Kray twin, part Cabaret master of ceremonies).

A ‘delivery ‘is perhaps being made to another Lennox creation, a black-wigged, Nico-like, possible, drug addict.Stewart is the prostitute/gangster’s chauffeur in the limousine, himself masked by shades and at one point dissolving to a sinister puppet shot. It’s the ‘long black’ where sex and death collide in Siouxsie’s Melt, where genders blur (the last scene in Performance) & similar to the vehicle in which Bob Hoskins is driven to certain death at the end The Long Good Friday. If London was ‘swinging’ again, its dark side was still ever present.

Dealer, Hooker, Junkie. We all have a price. We all have an addiction. It was a grim sign of the times and a suitable visualization of what Stewart called ‘a contemporary love song’ for an individualized age. Lennox noted that if they could have put heroin and needles in the clip to drive the point home they would have.

Lennox would talk about the ‘bombardment of messages’ propagated by advertising and ‘how an individual, male or female, must figure out who they are through this dense forest of identity and identification’. Her drag king Ziggy was peacock dandy, exploration of other personalities, a shy person’s collection of masks & a pop twist on Poly Styrene’s sociocultural critiques. On both 83 albums’ sleeves, Lennox appeared as an Ant-style Dick Turpin: the androgyne-as-outlaw. Eurythmics’ journey towards success was then as much about working out a visual identity as it was a musical one. Eurythmics briefly mutated into a Velvets-style art-house project. ‘The Walk’ featured a recently unearthed video directed by Royal College of Art student, Marek Budynski.

Their sleeve designer was a recent London College of Printing graduate, Laurence Stevens, whose influences ranged from the art movement Bauhaus to Bogarde, the perfect accomplice to the band with their modern, hard glamour. The music sounded visual too. Sweet Dreams sounds like cinema. Urban traffic runs through closing track The City Never Sleeps, a darkly sensuous future b-movie of a song, a softer cousin to John Foxx’s Underpass & Ultravox’s My Sex with its ‘neon-lit’ world of skyscrapers and faceless ‘spark(s) of electro flesh’ When the Eurythmics song did make it onto the big screen, it was regrettably via the soft-core Kim Basinger/Mickey Rourke flick 9 ½ Weeks.

Early 80’s pop seemed like a volte face from all those X-Ray Spex, Gang of Four-style razor sharp observations. Yet oppositional vestiges abounded in New Pop, often sneaked in through the back door. The ‘Sweet Dreams’ single was accompanied by another ambitious video in January 83. Kraftwerk (originally called Organization) had brought the suit and tie aesthetic to pop music. Like many others, Eurythmics adopted the look, even aping the Dusseldorf band’s ‘showroom dummies’at the end of ‘Love Is A Stranger’s video. Similarly, ‘Sweet Dreams’ clip, directed by Chris Ashbrook, chimed with the upwardly mobile (for some) times.

The boardroom setting and business attire echo the ‘material’ dreams of The Human League (old League members Heaven 17 were covering similar ground). But surrealism and nature intrude, offering both a destabilizing irony and a culture clash akin to Peter Gabriel’s ‘San Jacinto’ & Kate Bush’s ‘The Dreaming’. There’s also something almost self-mocking about Lennox’s gestures too, the gauche demeanour of a silent movie star playing a dictator. It is both a nod to Bunuel and Gilbert & George.

The video resists easy classification. The meditative lotus-like pose they sit in, suggests the song’s voyage is as spiritual as it is material. The gold discs then become a visual pun, both seal of status and symbol of universal wholeness. Beyond any satire about ‘making it’, Lennox seems to be asking that very 60’s question: who are we? The collision of two worlds, economic and spiritual is thus multi-layered. A prescient comment on how New Age thinking would so easily be assimilated by the corporate sphere. They pulled off the New Pop trick of having your cake and eating it; revelling in what you deconstruct.

It wasn’t just buried in the visual language of the video. The pounding authority of the song’s beat, supplied by the Systems Movement Drum computer (a Fairlight-like construction shown in the video) and catwalk ready strut of the bridge all suggest typical 80’s ambition. Yet neatly offsetting this is Lennox’s wordless wailing; the sadness that lingers under steely resolve. An update of the white existential gospel of Clare Torry’s on Floyd’s ‘Great Gig In The Sky’, it’s a subtly devastating touch. Sweet Dreams seems to exist on a cusp, more nuanced than the Gang Of Four (‘she said she was ambitious, so she accepts the process’), more genuinely ironic than Madonna’s ‘Material Girl’.

The ambivalence never really lets up. ‘I Could Give You (A Mirror)’ darkens its devotional aspects and perky Vince Clarke noodling with ‘disappointment’. As far as songs involving mirrors go, it’s somewhere between the tenderness of the Velvets’ ‘I’ll be Your Mirror’ and the late 70’s paranoia of The Beats’ ‘Mirror In The Bathroom’. Or even X Ray Spex’s ‘Identity’ where the ‘image ideal’ mirror of magazines becomes broken shards which the song’s conflicted subject slashes themselves with. Lennox’s offers a mirror, an appropriate prop for the narcissistic times, but it only reflects sorrow.

‘Sad and pessimistic’ is how Lennox described her mind-set then and through much of the 80’s. Eurythmics early music has an almost bipolar mix of rapture and disenchantment. For every ‘I’ve Got An Angel’, with its steam-rising erotic urgency and flute passages, there’s a ‘Jennifer’. The second song about an orange haired girl ‘underneath the water’ culminates in a musical funeral procession as elegiac as Joy Division’s ‘Atmosphere’. There are, in its morbid purity, traces of the Scottish folk music Lennox loved (Stewart too was a reformed folkie).

Eurythmics were too young for hippy (in Lennox’s case certainly), too old for punk. And yet hangover guilt from both simmers in their work. Everything in their world, from fame to love, was a very bittersweet proposition. Others were (post-punk) conflicted. Again Bowie’s ‘Fashion’, with its ‘don’t/dance with me’ set the scene. It highlighted the neuroses behind the ‘grim determination’ of the Blitz-kid facade.

Heaven 17 had Penthouse & Pavement/Luxury & Heartache, Soft Cell ‘Say Hello, Wave Goodbye’. This was pop music sound-tracking an epoch of division, of wealth and poverty, of opportunities and exclusion. Sweet Dreams’ lustrous cine-pop and the band’s photogenic allure all spelt luxury. But its songs of urban alienation in rented rooms with faceless strangers (‘The City Never Sleeps’) bear an odd resemblance to Steven Patrick Morrissey’s Whalley Range squalor. It was just relocated to Beineux’s Diva or Ridley Scott’s Bladerunner in Eurythmics ‘always sleek, occasionally gritty’ universe.

Eurythmics would cover ‘Last Night I Dreamt Somebody Loved Me’. There is at times in Lennox’s lyrical viewpoint a very kindred sense of ‘horror’ at the dating game. Punk opened the floodgate to a deluge of assertive female voices. Now the ‘strange little girl’ of popular song (The Doors, The Stranglers, Bowie) had started to write her own. But as with Morrissey, Lennox’s scepticism protects an old-fashioned romanticism (‘all I want is the real thing, she opined on ‘The Walk’).

In November of the same year, Eurythmics released Touch. Now ensconced fully in Stewart’s Church Studios, the album was birthed in far less agonizing circumstances. Its lacquered perfection was assembled in just three weeks. At a time when so many were one-masterpiece wonders, Eurythmics proved to be made of sturdier stuff. The League deliberated over Dare’s follow-up with interim singles, eventually ditching Martin Rushent for 84’s uneven Hysteria. ABC reacted against their Horn-upholstered opulence with Beauty Stab. Soft Cell plunged fully into the gutter with The Art of Falling Apart. By contrast Touch was, if not superior to its predecessor, certainly a refinement of it. There were more emotional downpours (‘Here Comes The Rain Again’) & more hot love in sub-zero climates (‘Who’s that Girl’) on an A- side of top drawer pop productions. The B-side let their ‘other’ side loose: ‘Graces Jones in the Bush of Ghosts’ ethno-tronica, proto-Art of Noise slick sonic architecture. They almost sounded like the 80’s children of Joe Meek.

It was not to last. Balancing invention and mainstream success is a tightrope walk that few can sustain. There was one or two more journeys into the weird, the 1984 soundtrack, 1987’s Savage. But early 80’s shiny subversion from within often gave way to blandness as the decade went on. Accordingly, Eurythmics became the epitome of BPI/Prince’s Trust-endorse music: quality, establishment, mature.

‘Sweet Dreams’ was a number one single and with Boy George, Lennox graced the cover of Newsweek: the gender-bending poster children of Britain’s second invasion.By the mid-80’s, electronics increasingly receded into Eurythmics’ background, replaced by mid-Atlantic rock This shift, perversely enough, yielded diminishing returns chart-wise Stateside. It felt like a spell had been broken. Stewart & Lennox reunite sporadically. Their back catalogue is sprinkled with gold dust. And yet never have they really matched the consistency of the sad, strange and popular music they released in 1983.