From the perspective the years have granted, 1992 clearly stands as a watershed year in hip hop history. At the end of it, The Chronic – traditionally regarded as the book-end release that closed the genre’s canonical "golden age" – would redraw the rap map, pointing out new vistas for a music that went on to become pop’s commercially pre-eminent form. But 20 years ago, hip hop was still an outsider music – still synonymous with non-conformism and clearly in opposition to much of what pop was and meant. Yet hip hop itself had a mainstream of its own, dominated by music made in a certain way, with a definable sound, and clearly expressed creative and artistic values. None of those elements permitted the records to be judged successful based on how many units were shifted – despite all the talk from the artists about the money they were making or the cars

they were driving, hip hop hadn’t yet come to define itself in terms of the acquisitions its makers could amass on the proceeds a hit record brought them. When, how and why the music’s own internal value system switched is of far less importance than acknowledging that it did, and that, 20 years ago, this change was yet to come.

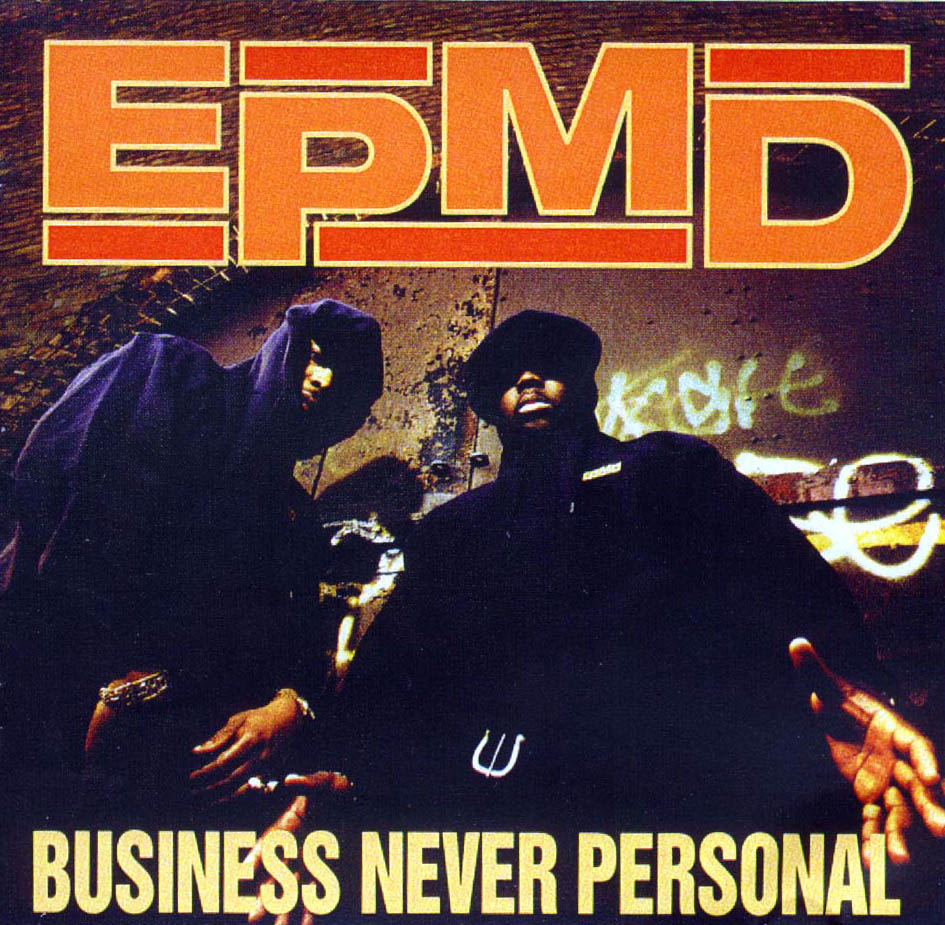

With all that in mind, a look back at the arrival of EMPD’s fourth LP adds a few shades of nuance to an understanding of what hip hop was and what it meant to the people who cared about it. Because, today, it seems strange that a record that was, in many ways, so unrestricted in its sonic approach would have been considered by fans to be, largely, an "ordinary" or even "middle-of-the-road" record – but such were the standards of what stood as hip hop’s mainstream at that time. Similarly, that the fourth

album by an uncommonly consistent band would have arrived to such

relatively muted fanfare seems odd today: EPMD were definitely among hip hop’s bigger guns, but perhaps the very fact that their quality control was so high meant that their fans’ expectations were similarly elevated, the arrival of yet another 40 minutes of thoroughly excellent music was just seen as (apologies) business as usual.

Whatever the reason, Business Never Personal didn’t seem a

particularly big deal when it came out in the summer of ’92. It was just another great record by a band who’d made three of them before, released amid a glut of similarly excellent LPs by artists both longer-established and up-and-coming. Though some listeners feel it’s mastered badly – and there’s certainly a frisson of frustration that the opener, ‘Boon Dox’, sounds like it was mixed in a sewer – it stands today as an object lesson

in how to make hip hop that was at once accessible and resolutely

hardcore: even at its most melodic (such as the Barbara Mason-sampling ‘Can’t Hear Nothing But the Music’, or ‘Chill’, built around a slowed-down loop from a Foreigner b-side) these are songs made inside a dense sonic fog, their hook-lines and tunes wrapped in artful abstruseness. As was their wont, EPMD continued to plunder the Zapp/Roger Troutman catalogue, but it didn’t matter: somehow

they retained the originals’ spirit and sonic signature without sounding like they were simply repeating past glories. And on the tracks where Erick and Parrish abandoned any pretence and just went for the boom-and-thump atmospherics – ‘Comin’ At Cha’, featuring protegees Das EFX, or the swaggering brass-scream-led contribution to the Juice soundtrack, ‘It’s Going Down’ – they merely confirm their status as one of the most intuitively capable and thrillingly assured hip hop groups of all time.

At the time, it seemed that this would be what hip hop would always be about – innovative artists, perhaps accidentally possessed of brilliance but possessed of it all the same, producing an endless stream of forward-looking, frequently dazzling, experimental-yet-conventional, genre-defining/defying LPs for the benefit of an audience all too easily accustomed to such a richly satisfying diet. But of course, it was destined not to last – not for hip hop, which took its unappealing and

ungainly lurch to the right in the years that followed; nor for EPMD, who, unbeknownst to most listeners, were undergoing their own internal traumas, and were about to depart the fray for a decade.

In 2007, as they were working on their second post-reformation LP, Erick Sermon and Parrish Smith were in London, and I interviewed them about the making of Business Never Personal. The piece ran in the late and very deeply lamented Hip Hop Connection, in an occasional series called The Blueprint which looked at the stories behind classic rap

albums and presented them, wherever possible, in an oral-history format. It wasn’t published online, so the only people who got to see it were the relatively small number who bought that particular issue of the mag. I therefore make no apologies for basing the remainder of this piece on that HHC article – expanded and augmented with material that had to be cut to fit the space available to the printed version.

When you meet Erick Sermon and Parrish Smith today, there’s no mistaking them: maybe the teenagers staring out from the sound board on the cover of 1988’s classic debut Strictly Business were more world-weary than we imagined, maybe they just have a good diet and exercise regimen, or maybe the duo are still hyped enough by their hip hop mission to look and feel

like youthful enthusiasts as they begin their third decade in business.

One thing you don’t get from EPMD today is much of a sense of conflict. Yet in the mid-1990s, when they seemed to be at the peak of their powers, the school friends’ relationship imploded in a welter of counter-accusations and recrimination. Parrish’s house was broken into by an armed gang; he would later imply that, if not directly involved, Erick had at least had prior notice of the incident. Since then, at different times, they’ve both had their say – Parrish perhaps more stridently. But with their relationship renewed, and a seventh EPMD album in the works, their mission is to accentuate the positive.

"We never goin’ talk about it," says Erick emphatically. "You heard what you heard, and that’s just it. Because right now we don’t wanna bring the negativity to something that we’re doing positive. The whole world knows already. You’ve heard it 25 times – you don’t have to hear it from us. It’s everywhere."

"We got past all that," Parrish says, "and that’s the lesson. If you sit on the negative side of it, then you don’t get to see everything that was really goin’ on. As you grow, you see it: but if you didn’t grow, it’s like you’d be sittin’ still. You sit still too long, you’ll accumulate weight – that’s what my momma says. So you’ve gotta keep movin’."

In 1992, EPMD certainly weren’t sitting still. Consolidating the success of their debut and its follow-up, they moved from Sleeping Bag to Def Jam and inaugurated their Hit Squad crew, the first fruits of which was a million-selling debut album from Das EFX. Before Wu-Tang came along and made the idea of extended families with their own deals on different labels a part of the fabric of hip hop existence, EPMD, Das EFX, K-Solo and Redman were blazing the trail. And somewhere, in the middle of the

touring, the production, the label and management intrigue and the splintering of their friendship, E-Double and PMD managed to make their best album, Business Never Personal (and one of rap’s all-time top ten b-sides, the mighty ‘Brothers from Brentwood, LI’). Here’s how they did it.

Parrish Smith: Me and Erick came in the game thinkin’ that you had to write your own music, produce your own beats, and do it from that perspective. We was already at momentum, and then when we would run into artists, they would already know, so they would come self-contained. We ran into Redman, you know: it’s not like we had to go find Redman. We did a show with Biz Mark

at Club Sensation in New Jersey – Redman’s there. He knows how he wants to put his stuff together. So it was more or less a work ethic that we was keepin’ up from the beginning when we got introduced to the game, with Russell [Simmons] and Lyor [Cohen] and gettin’ put on the Run’s House tour.

We was with Rush [Simmons’ management company] in the beginning – ‘cos, you know, the hype – but then me an’ E just felt like we could do it ourselves. They [the label] would totally confuse you. People wanna change your hair colour, they wanna change your style, they wanna change your image, they wanna change your hi-hat, they wanna tell you to do this and do that, but that’s not you. There’s six billion people in the world and nobody has the same fingerprint. You know you have to bend and work with them – it’s just a question of how far you’re gonna go. We were just fortunate to be with a hustle, like Russell an’ them,

and then for us to be from Long Island.

The best part of livin’ in Long Island was that we just became

self-contained. We would make the hour-and-a-half drive in to

Manhattan, have the meeting, then you have an hour-and-a-half ride back, and be like, ‘Yo, this is crazy’. Me an’ E would be clear what we wanted to do – super-clear. Soon as we go into Manhattan, nothin’ we wanted to do would get done and we’d be like, ‘Yo!?’ But we’re artists, and we know about hip hop. We know how music goes. So we took control of our career and our destiny to get a direction, and that’s when we set up our own management company.

Erick Sermon: You have to understand, too – any other group on Rush Management, they wasn’t EPMD. EPMD was EPMD, and we had a number one group [Das EFX] on the charts that was platinum. So it was a little bit more powerful, so they had to look at it different. And they were all on our album, so people knew they were comin’.

PS: A lot of these tracks was done in the mountains. It was like you need to pull yourself out of the regular flow of life so you can really focus, and sit there with no phone, no chicks, nothin’ – only the equipment. So we would go to this place, Bear Mountain, in upstate New York. That was the inspiration.

ES: It was a big mountain. It’s a resort, like where you have… it’s for comfortability. You got a TV, but the TV’s tiny. You’re not up there for that – you’re up there for the focus, and to get right. I was tryin’ to get my body right at the time – I was liftin’ weights and whatever. I lost mad weight up there!

PS: It was just me and E. And one night, actually, we were just

sittin’ there, workin’ on our music, and the guy who worked on

Juice knocked on our thing. It was like, ‘Yo’.

ES: Ernest Dickerson. I don’t know how that happened! So that’s how we ended up on the Juice soundtrack.

PS: After that it was outta control – but we did have some tracks: ‘Chill’, ‘Boon Dox’, and we did ‘Brothers from Brentwood’ up there too.

ES: All the classic LPs you liked back then were dope. You got in, you got out. There was none of this, we prolong you, drag it out, the whole nine-nine. I think the best albums were the ones made back then – 35, 40 minutes of your best work. Of real nice records. You can have an hour of bullshit, but I’d rather have the consumer made, like, ‘It was too short! We want more!’ You know? So every nine months we came back out.

PS: You never fast-forward though an EMPD album.

ES: Nor none of the albums made back then neither. You played that Eric B & Rakim album for a year. Public Enemy, Boogie Down Productions/KRS ONE? You played that for a year. Tribe, whatever it was, the shit just went constant, because they was good records.

PS: There were several reasons why we left that song [‘Brothers from Brentwood, LI’] off the album. At that time, that was just the way things was goin’, you know? We was makin’ so much music, and we kept switchin’ labels, from Sleeping Bag to Def Jam to RAL, but we was in control, so it was just a song for us to give to the ‘hood. Also, it was the b-side of ‘Crossover’, which maybe was a risk as a single, so on the b-side we covered our ass. That’s why I starts it off with ‘EPMD fans stay focused’.

We did that up in the mountains. I remember, we did it with a scratchy record, and you [Sermon] said, ‘I’m gonna do this, then later I’mma get the clean one’, and re-do it. And we never got the clean one!

ES: I can’t remember what the break was now – only that it was so

scratched! The record was some… it just sounded disgusting! The scream at the beginning? That wasn’t James Brown, that was me! Outta control. And as for sampling other tracks for the chorus…

PS: Oh yeah – ‘Massive meltdown, bring the red tape’ [from Nice and Smooth’s ‘How to Flow’]

ES: You did that in hip hop! It was like, Premier or anybody else would do it, so you used it too. I thought it was OK to use it.

PS: Our workin’ relationship was me an’ Erick, just… lovin’ each other. We’d just go in the studio and get a vibe on it. That’s what it is! A lot of times, we knew the format of where it would take EPMD. That’s why we were so dangerous, and that’s why, when it comes to production and beats, we’d go into the studio and have a lot of loops in our heads and then we got the crew, so the crew also let you know. That’s what actually helped us here – after Business As Usual, Das EFX came and set EPMD up. Boom-skiddly-bump, before we even got here!

ES: We went with the same records because that’s what we felt. We

didn’t know about anything apart from if it felt good. That was what we liked – we liked funk music. Parliament-Funkadelic, Roger Troutman – that was our sound. Then after us, Redman sounded like a EPMD record. [Redman’s debut] Whut? Thee Album was almost, like, doin’ us. When I was makin’ Reggie’s album, I was in the same mindstate of EPMD, Roger

Troutman, Parliament, Funkadelic – same type o’ formula. The Hit Squad had rap in a hold! All the time, the next one’s gonna be comin’ – after Red it was Keith Murray, but he wasn’t able to make the Hit Squad. And we’ll never know what woulda came after him. Right after then, when EPMD left, Dre went rampant. When the Hit Squad was out, nobody was really makin’ it. ‘Cos you had to be careful – we had it sowed up! But then Dre, he used

every record possible on ‘Dre Day’! And he came right back and used the same type o’ melodies on the Snoop record [Doggystyle]! ‘Cos it’s what you do – once you got that, that feels good to you. After that, we couldn’t use every Parliament or Zapp record. We knew there was more on there, so we went back to what was left. But by the time me and Parrish

came back with Back in Business, there was nothin’ left to sample! Dre used it all!

PS: We kept using Zapp and them for samples, but each time it would be different. That was the whole point.

The other signature style was that the samples weren’t always tight and precise – sometimes they’re off just a little bit, and, like the rhymes, the sound gets slurred, blurry round the edges.

ES: Yeah, because that’s what hip hop music was! It was not quantised. Funk music just goes. It’s sloppy. We used to stack like four, five samples on top of each other, and the shit would sound good. That’s bugged out – it’s crazy, right? I don’t understand that shit either.

PS: And you follow it. Whatever your track locks up into, you lock in. And then you, as a listener, know that.

PS: After we came down from the mountains, we started goin’ to the studios. By then, we had the frame of the album. I just found a tape, which I got to show E when we get home, of when we was in Dave Rockin’ Real’s [studio] with Redman, when he had the original afro. For me to try to explain in this interview wouldn’t make sense, so I gotta put it on DVD. But he basically said everything that was gonna happen, but he was in the studio while we was doin’ it when we was actually doin’ the song,

‘Headbanger’. We did like four songs [from Business Never Personal] at Dave Rockin’ Real, and we even did ‘Can I Get It Yo’ with Run DMC. That was big! [Jam Master] Jay did about 300 push-ups that night! We were supposed to do a video to that too. That was a good song. But, yeah, the frame of this was already done and it was there, so we just came back down and executed it.

PS: We was learnin’ about the world! That’s what it was about. We

were just young kids from Long Island with a dream. We put the name together, and boom – seventh greatest of all times. We could have dropped the first single, and nothin’ – nobody wanted to touch it, and we’d have had to try to go back to football or something. But it worked.

ES: It took five years, and what happens is, we was really blowin’. We was kids, and things got out of control, and we couldn’t catch it. We had our own tours, we didn’t need to be on tour with nobody because we was the Hit Squad. We had four people on the charts at the same time – all ours.

PS: You know, we had the market cornered. We came in to see the

Run’s House tour and thought, ‘We could do this’, and really did it. And it’s still happenin’ now. That’s what I’ve learned – I learned so much from E, I learned so much from Keith [Murray]: it’s a very, very humblin’ experience. It’s good to be within a covenant. Not too many people have that.

ES: And even though we broke up at that time, you got people like Snoop and Dre, who only did one record, and after that they was dead. So we… it wasn’t like there was no situation – we put five years of top work in, four great LPs before that [the split] happened. More than anybody else. We don’t know nobody that was in that era that had consecutive LPs like that. Back to back. You name me one that had four back-to-back dope LPs! Apart from PE.

PS: And the moral to the story is, a lot o’ people don’t get a second shot, you know? So for me, personally, I was connected to some other type of different energy that I had to let go, and then letting that go, boom – lucky you got a good partner, good balance. The rest is all bullshit – that’s how I really honestly feel.

But there have been times where you’ve felt very differently, and talked about your feelings on the background to the split in interviews.

PS: Yeah, no question.

ES: He always will, but it still don’t matter. Because, by him sayin’ that, if it was done effective, this [reunion] would never happen. Evidently it must’ve meant nothing, because we don’t need the money. We sit here because we love what we do. This is what we feel. Jam Master Jay died, so Run DMC can’t perform no more. After Run DMC comes EPMD, so we are obligated. All this stuff that we’re goin’ through, yo, it’s the ones that’s next that we’re lookin’ at. We don’t even go into what happened, because it didn’t mean nothin’. We here for a purpose, and the purpose is to save a dying culture. We’re not sayin’ we’re tryin’ to bring it back to where it used to be, we just want balance. Every interviewer, every radio station, everybody, they always have the same complaints, which is the truth: ‘Yo, what happened to our creativity and excitement?

Where’s our emcees?’

PS: Like E says, everybody’s cryin’, but the truth of the matter is, we stopped workin’. You had Hammer and Vanilla Ice, but yo, we still had Slick workin’, we still had EMPD workin’: we still had everybody, so it didn’t matter how much the crossover went, we still had hip hop. But now…? Nas was just the first one to come and say it.

ES: Everybody got discouraged ‘cos the South made such an impact that everybody just stopped workin’. And that’s how we lost our culture. Forget about people not playin’ the songs or not representin’ – we lost the culture ‘cos hip hop stopped workin’. We stopped makin’ albums and we stopped doin’ things.

PS: Come on, man – we can’t turn our back on something we put our

life into full-steam. And the best way to show people is by demonstratin’ by example.