Near self-destruction was synonymous with The Wildhearts from the precise moment of their conception. The legend goes that after being sacked from The Quireboys for boozing too heavily, the mononymous Ginger had an epiphany while tumbling down the stairs of Seven Sisters tube station. In that split-second moment, Ginger decided that if the empty bottle of Jack Daniels he was clutching were to smash, he would slit his wrists using the shards of broken glass. If the bottle remained intact, he would form a new band.

It’s safe to say The Wildhearts never really fitted in anywhere, they didn’t exactly help themselves with their erratic antics, and were prone to contradiction from the outset. In thrall to US classic rock as well as newer groups such as Guns N’ Roses, Ginger’s singing voice often sounded for the most part more affected American than native north-east English, yet the opening track on The Wildhearts’ second EP (‘Turning American’ from 1992’s Don’t Be Happy… Just Worry) lashed out at musicians who frivolously abandoned their British roots in pursuit of international superstardom.

The unashamedly ambitious, melodic rock that The Wildhearts worshipped and replicated had been shunned by grunge, and then grunge (itself another form of ambitious, melodic rock albeit a more self-conscious or at times ironic one) withered in the wake of Kurt Cobain’s suicide in 1994. In the UK, this coincided with Britpop’s outspoken rejection of Americanism, resulting in a hysterical degeneration to 60s mod-ness. A 1996 recording of The Wildhearts’ performance at Radio 1’s Sound City event in Leeds captures Ginger asking the crowd to buy his band’s latest single. "Put us in the realms of The Bluetones and Pulp," he pleads, "we wanna be fucking pop stars."

They were never going to be fucking pop stars. They were rawer than grebo, too hard for indie kids, too bubblegum for metallers and, exacerbating the dilemma of their unfashionable sound and image, The Wildhearts were their own worst enemy. How should we put this? Imagine filling a rickety barrel with all nails and Poundland sandpaper. Now imagine stepping inside that barrel and, immediately after firing an inexcusably offensive text message via the send-all button to every contact in your smartphone including your boss and your mum, rolling down the steepest slope in all of Christendom while simultaneously punching yourself in the teeth. The Wildhearts were approximately 37 percent more self-sabotaging than that.

For example, moments before his Bluetones quip, Ginger had announced that he was not permitted to swear on Radio 1’s live broadcast. "…But you are," he added, instigating a mass chorus of "fuck"s and "cunt"s from his audience before going on to drop the f-bomb himself several times anyway.

If they were too unruly for Radio 1, you would’ve thought that The Wildhearts’ shtick was right up the street of the writers and readers of Kerrang!. Home-grown with heavy riffs and catchy hooks, surely the group had the potential to be the magazine’s eternal darlings. Even this relationship was fraught. When the magazine hinted that bassist Danny McCormack might be leaving the band in 1995, The Wildhearts retaliated by marching into the publication’s offices to smash up the offending journalist’s desk.

In June of that year, their second album reached a laudable number six position in the album charts despite its vaguely provocative title, P.H.U.Q. (pronounced "FUCK"), although further success was marred by personnel instability and a bitter relationship with their record company, East West. In March 1997, the band signed a four-album deal with new label Mushroom right outside the offices of their old label as if they were The Sex Pistols or something. Mushroom would receive only one of those forecasted albums. And the album in question would be a complete bloody mess. But, oh, what a glorious mess.

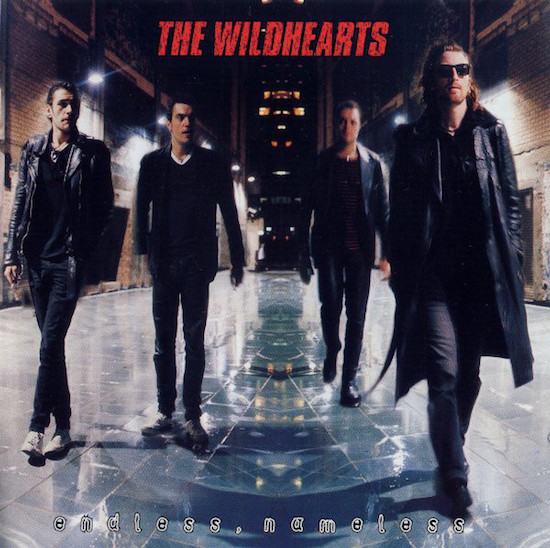

It is far preferable to go out with a big old bang than a protracted wee whimper, as Kurt Cobain didn’t write in his suicide note. Putting to one side the tragic individual breakdowns that might colour our assessment of In Utero, The Holy Bible, Closer, et al., which record best encapsulates the sound of a whole band imploding in unison? Dinosaur Jr’s Bug? That Fleetwood Mac one with the wife-swapping? The harrowing existential wail into the indifferent void that was Spice Girls’ Forever? Incorrect. The best band implosion record of all time is The Wildhearts’ deafening moment of career hara-kiri that was 1997’s Endless, Nameless.

Abandoning the sentiment of The Wildhearts’ 1996 single ‘Sick Of Drugs’, Endless, Nameless was recorded in the midst of epic substance problems responsible for a string of shambolic live performances and the band’s split right on the eve of the album’s release. Bassist McCormack was in the worst state, having succumbed to full-bore heroin addiction. Drummer Ritch Battersby was said to be getting his kicks from ecstasy. Newish guitarist Jef Streatfield ticked the "pothead" checkbox. For his own part, Ginger began experimenting with crack. According to the singer/guitarist, in an attempt to amend the disunity exacerbated by the members’ disparate drug preferences-cum-addictions, the band all took to whizz. When that failed to secure a cohesive plain of consciousness, they did what any sensibly minded group of professional creatives would do. They resorted to chasing speedballs.

That the band managed to produce anything of any value in this frazzled state could be deemed something of a miracle but it at least partly explains why the end product sounded, for lack of a more eloquent term, so completely fucked.

With McCormack regularly absent to score drugs, get high or collapse in the studio toilets, Ginger was left to lay down several bass lines himself. The record’s lead single, ‘Anthem’, was born from an attempt to motivate McCormack and in that case the bassist did come up trumps by writing a significant proportion of the song and temporarily taking over lead vocals for the first (and final) time. With its phat bass riff and "I’m in love with the rock & roll world" refrain, ‘Anthem’ would turn out to be the album’s poppiest number by a wide margin. Thanks partly to its release across multiple formats, the single reached the respectable chart position of 21. This earned the band an appearance on Top Of The Pops, the unhinged results being the closest any band ever got to sneaking Steve Albini’s abrasively metallic Big Black guitar sound onto primetime BBC1. For the promo video shoot, the band invited their friends to an aircraft hangar and spent half the production budget on booze and drugs including a huge bag of pure MDMA to share with their fellow revellers.

‘Anthem”s more confusing and grating follow-up, ‘Urge’, fared almost as well, reaching as high as Number 26 which isn’t bad for a track which juxtaposed sentimental verses about going away for the weekend with sampled sex moans and a roaring chorus of "GOT TO BEAT THE FUCKER DOWN". (Bonus points for namedropping Ween in verse two.)

Though it had a more industrial sound than the band’s previous recordings, ‘Anthem’ only hinted at the challenging onslaught of noise that would be Endless, Nameless. Further alluding to the record’s uncompromising content, the album’s title was borrowed from the ear-splitting improv track hidden at the end of Nirvana’s Nevermind. (Ginger has claimed the title was a coincidence but his memory might have been clouded. He had, after all, already confessed "Oh God, I miss Kurt Cobain" on 1994’s ’29 x The Pain’ and, as the saying goes, if you can remember recording with The Wildhearts in 1997 then you weren’t something something something.)

Endless, Nameless‘ opening track, ‘Junkenstein’, starts loudly and only gets louder. Its volume slyly increases over the course of its duration, which made listeners wonder if their stereo was broken or wrongly wired or perhaps if their own ears were broken or wrongly wired. In the mistaken belief that this was an unintended manufacturing fault, many purchasers returned their copies to Our Price.

Thanks to a very game Ralph Jezzard at the production desk who helped to realise Ginger’s twisted vision, the record is swamped in thick layers of distortion, fuzz, static, grease, feedback and other aural ugliness. Impressed by how the power of electronic acts like The Prodigy and The Chemical Brothers seemed to be stealing rock’s thunder and even threatening to make it obsolete, Ginger wanted to prove that guitar music could still blow people’s heads off and live renditions of his new compositions were conceived with the intention of making his audiences either vomit or involuntarily soil themselves.

Instead of messing with turntables like the nu-metal bros or purchasing a drum machine à la Big Black or Ministry, The Wildhearts crafted their own semi-industrial sound by fitting Battersby’s drums with D-Drum triggers which let off sampled sounds of explosions and car crashes. The noise was fed through partially broken PA speakers and the other instruments would have to be loud enough to square up against that malignant backbone.

The harshest track is ‘Why You Lie’. Its verses make ambiguous attempts to address the conflicting emotions of handling a buddy’s drug addiction (exacerbated by one’s own substance problems, no doubt) while the chorus gets to the core feelings of frustration and futility. The words "Why, why, why do you have to lie to me?" are screamed repeatedly with a near-unlistenable force. Owing to a newfound interest in soundscapes, the band "wrote" long, blank sections into their songs to be filled by improvised chaos. The middle section of ‘Why You Lie’ contains a sample from Lucio Fulci’s cult horror film The Beyond: a little girl shouting "Mummy" before a woman’s face is splashed with acid. Looking back, I realise that this record may have been my first exposure to "noise music" and you might be able to trace my later enthusiasm for Merzbow, Wolf Eyes or Hair Police back to being mentally traumatised by this thunderous ordeal from the same people who’d brought us the pop-rock mini-smash ‘I Wanna Go Where The People Go’.

Having said that, Endless, Nameless still has some tunes in it, struggling to escape in the maelstrom, if you listen closely. As well as ‘Anthem’, there is the tainted cover of Dogs D’Amour’s ‘Heroine’ (its title altered to the more forthright ‘Heroin’). The warped glammish stomp of ‘Soundog Babylon’ has a proper pop chorus buried in it somewhere and, following its own blaring white-noise section, features a pleasantly clean, slow breakdown. ‘Pissjoy’ even has plenty of "la-la-la"s courtesy of a bratty children’s choir. (Did anybody inform social services?) Seven-minute closing track ‘Thunderfuck’ begins as a skewed trip hop deep cut mutated with a lighters-in-the-air sway-inducing rock ballad and ends with Ginger repeating the refrain "And with the world in his ass" ten times or so with added "ba-ba-ba" backing vocals. Various discombobulating samples are layered over the top. There is a scream. Some kind of explosion. A guitar being destroyed? Something has been destroyed. The record is over. The band is over. Thank you and goodnight.

Twenty years on, I’m not convinced Endless, Nameless changed anything. Ginger’s mate Devin Townsend borrowed some of the album’s noisy bits for his own post-nervous-breakdown record Infinity, but you don’t see Endless, Nameless being touted as an influence by any other groups. In November 1997 most of the nation was still too busy basking in the light of Tony Blair while solemnly mourning a dead Princess to take heed of a harrowing scuzz-drug-metal record. The gnarliest thing most people were interested in was that bloke from Reef growling his three-word catchphrase, "It’s Your Letters", on a weekly basis.

Granted, Britpop itself had taken a darker turn by that year. Blur had swapped Hackney and uppers for lo-fi and heroin. Oasis were lost in a gak-addled fug. Primal Scream were on a dubby comedown. Black Grape went off the rails. Radiohead hit a new level of pre-millennial paranoia. Pulp were working on their "difficult sixth album" which would turn out to be a 70-minute sermon on why achieving your dreams ain’t all it’s cracked up to be, yeah? Next to Endless, Nameless, those efforts all look about as tortured as Cliff Richard’s Songs From Heathcliff.

The album has had few trumpeters other than a select group of enthusiasts on The Wildhearts’ internet forum. Many of the band’s followers seem to view it as an illegitimate, mutant hatechild, fit to be drowned in the lake with nothing more said about the whole sordid affair. Kerrang! once listed it as an album to avoid at all costs: "A couple of good tracks make it out of this static-fuelled, industrial-strength mess of an album, but not enough to warrant its purchase." Sure, sometimes you have to turn it off immediately because it’s too overwhelming. Sometimes it sucks you in. It remains forever in my iTunes library, hibernating there for when I need it to blow out the cerebral cobwebs. Rarely has the sound of a band collapsing under an avalanching cocktail of drugs, bravado, self-hatred, semi-failure, jealousy, near-success, anger and paranoia been bottled so finely. You could say that it was the loudest, noisiest, brashest, maddest mess of a record to ever penetrate the Top 40. You could say that. But in a typical instance of Wildhearts underachievement, the record peaked at number 41. It would have been the best band-split album of all time too. Again, they even fucked that up, reforming hastily afterwards to honour Japanese touring commitments, disbanding once more, and reuniting sporadically in the years since.

A few months ago, Ginger came dangerously close to the edge once more when he attempted suicide (not for the first time) after an altercation with an audience member at a concert in Northern Ireland. Thankfully, he survived. Near self-destruction is all well and good and can make for a nice juicy anniversary piece of rock writing. Actual self-destruction is a bummer of the highest order for everybody concerned.

Interspersed by those sporadic Wildhearts reunions, Ginger’s post-Endless, Nameless career has birthed countless compelling side-projects and solo records ranging from outlaw country aliases through unabashed power pop and duets with Courtney Love to at least one Eurodisco love number dedicated to his Ginger nicknamesake Geri Halliwell.

The heavier and experimental tendencies that debuted on Endless, Nameless have since been channelled into Ginger’s Mutation project whose furious electro-tinged grindpunk racket makes The Dillinger Escape Plan sound about as metal as that band that’s got Jared Leto in it. Mutation will be on tour this month in support of their third album Dark Black (easily their nastiest outing to date). Don’t forget your earplugs. Drop a pre-emptive imodium on the way to the gig. Pack a sick bag. It’s going to be a loud one.