When Donald Trump gave his defiantly downbeat ‘American carnage’ inauguration address, one sentence stood out as particularly strange: "We stand at the birth of a new millennium ready to unlock the mysteries of space, to free the earth from the miseries of disease and to harness the energies, industries and technologies of tomorrow."

This is not the space race of the Kennedy era. In fact, it is a cruel piece of self-fulfilling prophecy. It points to the diversion of NASA’s efforts away from climate change and in doing so potentially hastens the means of our race’s destruction. A new mission to unlock the mysteries of space itself creates the circumstances from which we’d seek to escape. And at the moment Elon Musk and his ilk can only guarantee a one-way ticket to Mars, with no promise of actually getting there.

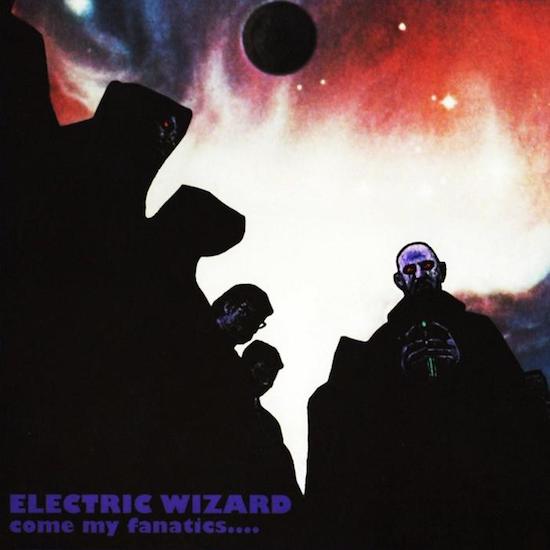

Twenty years ago saw the release of Come My Fanatics…, Electric Wizard’s second album. It is a towering effigy of doom metal; a monolith suspended outside of time and space that sounds like nothing before or since. An hour before the inauguration I spoke to Jus Oborn, founder member, guitarist and singer. The album seems to have given birth to the twenty-first century: paranoid, chaotic, visceral and bent on annihilation, although it was conceived at a relatively ‘quiet’ moment in history during the summer of 1996 and released in January 1997.

Oborn disagrees: "It was a similar period in history. I think it always is. I don’t think that anything changes from that point of view. It’s just different baddies involved every time. It didn’t feel like it was a simpler time. There was still things to be scared about then: the threat of nuclear war had only just gone past. Our country wasn’t in a great state. And metal was totally fucked at that point. We were really making a musical statement. When you’re younger everything is a reaction against the world."

The album begins with ‘Return Trip’, a molten re-entry into the atmosphere which is sonically shocking. The blown-out sheet noise of on-the-brink valve amplifiers assails you first, then Tim Bagshaw’s slow and browbeaten bass riff, with Mark Greening’s drums lost under geological layers of distortion. Here is heavy music in all its weirdness – teeming and flooding onwards like billowing toxic gas.

When the guitar comes in the bite and aggression stand out, the riff brutally nailed to the cross, a two-note swinging pendulum of destruction with a sting in the tail; before a loping, emphatic second section, then what sounds like exhausted collapse, through which is squeezed a sample from lurid 1981 exploitation film Cannibal Ferox: "Get off my case, motherfucker!"

In all, it is over two-and-a-half minutes before the collapsed-lung blues of the main riff is initiated and one of the best opening lines in heavy rock: "The sun burns in the stranger’s eyes/ Just one tear before he dies." Oborn wails like a man hurtling towards his own destruction, all afire before it wrenches itself through its final few minutes like the spheres grinding together. It is self-immolation in song form and exudes a magnificent, white-knuckle nihilism that feels very now: "I hope this fuckin’ world fuckin’ burns away/ And I’d kill you all if I had my way."

The album was conceived as a piece of escapism, one that Oborn explains was born of an "insular, underground feeling that we were heading to our doom as a planet and no-one overground had a fucking clue about it." The idea of underground culture here is of a bunker mentality found in the subterranean world of 1970’s Beneath The Planet Of The Apes, inhabited by what its poster described as "radiation-crazed super humans". The planet is destroyed at the end of the film by a doomsday bomb. The closing narration is sampled at the end of the fifth track of Come My Fanatics…, ‘Son of Nothing’: "In one of the countless billions of galaxies in the universe, lies a medium-sized star, and one of its satellites, a green and insignificant planet, is now dead."

The sun – alternately burning and dying – is integral to the lyrics of the four songs with vocals on the album, whereas "the morning star" Venus is "burning bright" during ‘Doom-Mantia’’s moonless seance. The "thirteen" gathered there are involved in some kind of Crowley-esque ritual, whereas "the chosen are ready" on second song ‘Wizard In Black’ as the "chaosphere seethes behind". Oborn returns to the idea of the chosen few repeatedly in Electric Wizard’s work and here the wizard attains godlike status through occult practice, but ultimately is no match for the void that is the universe.

Come My Fanatics… is really Electric Wizard’s science fiction album: "The whole B-side of the album, the last three songs, is a concept about leaving earth because it’s so fucked up. The idea was we’d try and escape our universe for another planet to live on, but never find it. That’s always been the Electric Wizard ethic: the world’s heading to some sort of environmental disaster, and the powers that be aren’t doing anything about it and don’t care about the poorer people. So that was behind it all. It might seem more widely recognised now, but that’s more to do with the internet and people’s education about the way the world is. Back then you were considered quite a paranoid, underground freak if you thought the world was controlled by the powers that be and no-one really cared about us."

Oborn had been impressed with Arthur C. Clarke’s ‘Childhood’s End’ (1953), about a supposedly benign alien race called the Overlords ruling humanity. Escaping a dying earth is a common motif in science fiction. In Richard Matheson’s 1955 short story ‘Third From The Sun’, he writes how "in a few years, probably less, the whole planet would go up with a blinding flash. This was the only way out. Escaping, starting all over again with a few people on a new planet." The twist being in this story that their destination is actually Earth. Self-induced planetary cataclysm is not necessarily unique to our solar system.

Space rock has its place too: ‘Son Of Nothing’ and its demo title ‘Return Of The Sun Of Nothingness’ deliberately borrowed the names Pink Floyd used for working versions of the epic ‘Echoes’. The band identified strongly with the concept: "We were the sons of nothing – we were going to inherit no world because it was going to be destroyed by the people above us."

But the Urtext for this genre of heavy songwriting is Black Sabbath’s ‘Into The Void’. Pre-Ozzfest resurrection, Sabbath were deeply unfashionable in the mid-nineties but Oborn cleaved close to their riff-centric songwriting and heft.

From Sabbath’s third album Master Of Reality (1971), ‘Into The Void’ is lumbering, it is slack, but it moves together with an awesome intensity and momentum. On top are Ozzy’s vocals: unnaturally high, slightly strained, recounting the tale of escaping terra firma "up into the night sky" and "through the universe". This is a panoramic interstellar journey, leaving for the ether, "burning metal through the atmosphere", escaping the onset of apocalypse on Earth that "remains in worry, hate and fear". It encapsulates the nascent metal genre’s inherent escapism, the urge to leave the world "to Satan and his slaves" and head towards the sun, the light, oblivion: "Rockets flying to the glowing sun/ Through the empires of eternal void/ Freedom from the final suicide."

After the super-heavy but definitively rock core of the first three tracks on Come My Fanatics…, ‘Invixor B/Phase Inducer’ comes as a surprise: an instrumental intended to depict a graveyard of ships floating in space. This piece starts with a heavy psychedelic jam and soaring female vocal that came about by accident when the band decided to try out the drum & bass sampler lying about in their Bournemouth studio: "A lot of people around us were into electronic music and early drum & bass, and we were quite impressed, even though we didn’t like the music. There was quite an emotional resonance when terrifying samples were used in that music. Stuff like ‘6 Million Ways To Die’ seemed quite brutal in the use of samples and that was something we thought we could bring to our music."

Much of Electric Wizard’s musical quest was to find what was being hidden from them, what they were not being allowed to see. The horror film samples came from the video nasties passed under the table at the market stall in the ‘Lovecraftian’ town of Wimborne in Dorset where they all lived. Oborn read controversial magazine Answer Me! (edited by the aptly named Jim and Debbie Goad), which only survived four issues between 1991 and 1994 before being the subject of an obscenity trial. Its recently published anthology describes it as a "big black slab of trouble" containing everything from "music and subcultures to sex, love, hate, murder, serial killers, and suicide".

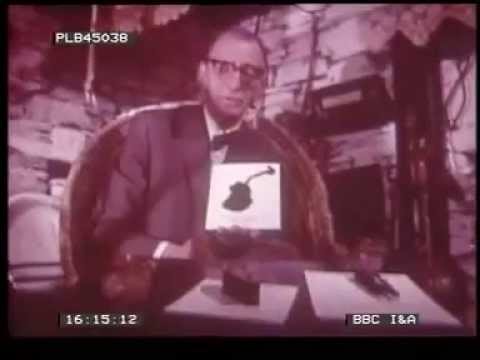

The cover of Come My Fanatics… depicts Anton LaVey and his disciples, and is a still from a 1971 documentary called The Power Of The Witch, which is now a click away on YouTube (the shot in question is at this point). At the time Oborn had to pause his taped copy and trace the image from his television and later provided the incandescent universe as background, to pull the coven out into space.

HP Lovecraft is a cornerstone of internet culture now, particularly his Cthulu mythos, and is more directly referenced by Oborn on 2000’s Dopethrone, but his ethic underpins Come My Fanatics…: "He was an influence all along because I read him when I was 13/14 years old. Lovecraft himself had this idea that art should be otherworldly and have this sense of fear and something beyond our understanding. I took that as more of an influence than literally talking about tentacle-headed monsters, which only crosses the surface level."

Oborn found their producer Rolf Startin in the Yellow Pages (he had previously worked with Neneh Cherry and Alexei Sayle), and he was prepared to build the studio around them, with an array of vintage amplification pushed to the limit and shared the band’s desire for rawness and feeling: "It’s a very technically inept album. It’s very difficult to deliberately do things badly. It just happened. It was exactly the sound we were trying to create."

After this record the band began to focus more intently on the occult, concerned that, like the titular ship of closing track ‘Solarian 13’, they would be doomed to drift through the universe with no destination: "We’d gone too far into space and then started looking for earthly horrors a lot more."

Oborn looks back at Come My Fanatics… as the best of the power-trio era of the group, even though Dopethrone is often cited as the band’s masterpiece: "It’s my favourite of our earlier stuff. From this point of view now I can’t honestly remember doing it, so it is like listening to another band and I do like that album a lot. I remember doing Dopethrone and it was particularly hard work and a miserable experience so I don’t look at it fondly."

There are stronger musical ties between the two periods of the band than initially appears. One of the interesting tidbits of this period, and of the circularity of influence, is that ‘Return Trip’’s opening riff is heavily indebted to the main riff in 13’s ‘Whore’, a point 13 guitarist Liz Buckingham made to Oborn when they first met. She clearly understood that genius steals, since she put the matter aside and went on to join Electric Wizard and has been on second guitar since 2004’s (criminally underrated) We Live.

If the twentieth century’s Big Dream was to escape earth in search of new worlds to inhabit, Electric Wizard showed it in a new, wild-eyed light. Desperate, mind-blown on weed and acid, and resolved to destruction, Come My Fanatics… is appropriate listening for the new world disorder unfurling in front of us. Prepare the escape pods; watch it all burn.