“I didn’t ask to be made: no one consulted me or considered my feelings in the matter. I don’t think it even occurred to them that I might have feelings. After I was made, I was left in a dark room for six months… and me with this terrible pain in the diodes down my left side.”

Thus spoke Marvin the Paranoid Android about his coming into the world. Marvin was made famous by his appearances in Douglas Adams’ popular 1978 radio series, Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy and later adaptations for TV, book and film. His downbeat appraisals of the nature of existence reflected the fractious paranoia of the late 1970s and early 80s. Marvin’s soliloquy could also have been written for Echo & the Bunnymen’s third long player, Porcupine.

Marvin had many talents, including an intellect that could have solved most of the Universe’s problems, had his human masters asked him to engage with the task but, being a robot, never showed a nipple on the telly. Unlike the Bunnymen’s totemic singer Ian McCulloch, who, in January 1983, channelled his sense of occasion during the band’s mime of a terrible “live” pre-recording of album lodestar, ‘The Cutter’, on Top Of The Pops. Mac’s inner Ziggy took over as his top – two black sheets held together by pins – slipped down below the Mary Whitehouse Line.

On the Bunnymen’s TOTP debut six months earlier, for what would end up being Porcupine’s lead single, ‘The Back Of Love’, the audience included a clown-like character prancing about on stilts, wearing a Rising Sun top and flying helmet. Guitarist Will Sergeant remembers looking up and wondering, “What the fuck is that for? I didn’t want owt to do with it. Dead cheesy. Awful.” Way back then, in the deeply tribal world of pop music, these sorts of signifiers mattered. Would this most gnomic of bands live out McCulloch’s fears as expressed in the lyrics of album’s title track, and miss the point of their mission?

A week or two after Nipplegate, the spiky, psychedelic Porcupine was introduced to the world. Like Marvin, who stoically accepted his fate (one “almost as good as death”) of driving a spaceship into the heart of the blazing sun of Kakrafoon, the band battened down the hatches to deflect the heat of public appraisal and went on a bad tempered tour of the UK. Despite quickly reaching number two in the album charts, Porcupine seemed to piss a lot of people off. It was too complicated and weird for a general public fed their musical ambrosia by Simon Bates and Steve Wright. For those in the music press who had previously raved about Echo’s brilliant and precocious long players Heaven Up Here and Crocodiles, the record was at once too indulgent and antagonising. Many writers seemed enraged that Porcupine – warts and all – didn’t match their projections of what the Bunnymen should be.

Maybe the press sensed the fact that the slow production of Porcupine contained a slightly skew-whiff story of a number of creative worlds colliding. On one hand there was a very public, driving ambition, born of all that went before. The ambition to be “the best band who smoke cigarettes. Best band at everything,” to quote Ian MacCulloch in 1983. Mac once envisaged the band on tour as “a small human race, us and the crew”. The rest of this small human race felt a bit differently after three years of becoming a formidable cult band; “the biggest cults on earth” as Will Sergeant once put it. Back in 1982, after a 1981 that saw 113 shows in 169 days, all-action bassist Les Pattinson wanted to go back to building boats, mythic drummer Pete DeFreitas hung out with Liverpool romantics The Wild Swans, funding and producing their epic debut single, ‘Revolutionary Spirit’ and Sergeant hunkered down at home with his 4-track, making ‘Back Of Love’ B-side ‘Fuel’ and the mysterious film soundtrack that never was, Themes For Grind. Another factor that threatened to upset applecarts was the band management’s far more prosaic line of thinking, namely, “Fuck. We need a hit to keep the record label [WEA] onside.” Truly, it would be an attempt to herd cats.

Like Marvin, Porcupine was shaped by an all too acute understanding of the sacrifices it had to make, simply to be itself. The record was born mysteriously, as the Duchess of Malfi and Antonio’s son was, in Webster’s play. Firstly, the six month incubation of “weird” and, ultimately, rejected D-chord and Ray Ban-driven demos that were happily lost. Then a round of creative interventions and endless adjustments on the mixing board, followed by a last-minute overhaul in a matter of days. The process evokes another misfit born of mischance, Caliban, who was “litter’d like a puppy”. Like the son of Sycorax, Porcupine displays both wild mooncalf fancy and a belligerent ugliness that is “not honour’d with a human shape.” (We will come back to other Jacobean theatricalities in a short while.)

More prosaically, Will Sergeant remembers a “fragmented” recording process, strung out over three different studios. “We weren’t really starting in one place, it was all a lot of hassle, you know, stuff like moving drum kits around in the studios. But it gelled together in a weird way.”

A record that is the half of half-and-half, or one that’s the half that’s whole? Maybe all of it. But how to align all these halves? Why, via some half-evolved pop-magickal theorems and homespun Liverpool creative myth, that’s how, divvy. A number of mage-like and shadowy agents acted as gleemen, divining Porcupine’s chimerical character during its difficult gestation period. Bill Drummond, surely the band’s Prospero figure, tried anything to keep the band off the beaten track. A slot at the first WOMAD festival in the middle of a rail strike, playing Zimbo with the Burundi Drummers. A small, wyrd Scottish tour to raise spirits. It didn’t, but presented the unusual sight of uber-gifted Pete DeFreitas playing guitar now and then, and fellow traveller-cum-producer Ian Broudie both mix and play guitar live on stage.

Still, Drummond’s own take on “wild mooncalf fancy” still looked like it might pay off. Will Sergeant says: “Bill Drummond had teamed up with a guy called Steve Israel, who we met in New York. Steve played us a VHS with Shankar [Lakshminarayana Shankar, Indian violinist, singer and composer] playing this crazy double violin with five strings on each neck. He was playing one neck whilst keeping this drone going on the other. I remember us saying, ‘We’ve gotta get him on the record.’ We were at the stage of looking for things to make it sound different.” Many know the glorious warcry wail of ‘The Cutter’ (the most compelling intro to any mid-80s British pop hit apart from ‘Relax’ and ‘Blue Monday’) is a reinterpretation of Cat Stevens’ amiable pop tune, ‘Matthew And Son’. But, notebooks out plagiarists: the riff is taken from the fourth time the line “Matthew And Son” is sung after the "rent arrears" middle-eight: the bit with the reverb chucked on. That’s important. Will Sergeant adds: “Me and Broudie both claim that [referencing ‘Matthew And Son’ to Shankar]. And that reverb bit, we loved that, the one thing in a record that every now and then helps make a bigger idea.”

Shankar had previously added strings to ‘The Back Of Love’, also produced by Broudie, then going under the name of Kingbird, a moniker given to him by a depressed Liverpool mate who saw the musician as a magical figure. This guise allowed him to adopt a more shamanistic, interventionist role than merely being credited “producer” of a Bunymen record. In true Liverpool style Broudie saw the role behind the mixing desk as mythopoeic, an almost physical adjunct to the soul, akin to summoning up a creative unguent akin to the Cthulhu tales. The sounds of Porcupine were brewed up in the head after chats down the pub; half memories of instrumental lines that could be bent one way or another. A great deal of the weird, synthesised noises that make the album such a deep dive come from otherwise standard guitar parts that were later cooked up on the mixing board. Sounds heard on the title track, for example, where Sergeant and Broudie’s guitars were put through various pedals such as the Eventide harmoniser, and channelled through the mixing board.

Outside of his godlike drumming, Pete DeFreitas’s other musical skills found their head on the record: his urgent marimba solo on ‘My White Devil’ is surely the most rock use of any instrument in the xylophone family, outside of the late Sir Patrick Moore’s extemporisations on The Sky At Night. DeFreitas’ piano parts and use of other percussion such as slit drum and a “weird African marimba, held together with goatskin and with gourds as the sound boxes,” high in the mix – alongside the juggernaut bass lines shaken out by Les Pattinson – create a highly charged, theatrical backdrop. The music on Porcupine really can be seen as a vast, public stage set that has been created through mysterious and sometimes questionable arts. A stage set that is of the band’s, not the media’s, nor the public’s making. All that is needed is further artifice from the lead actor.

"You taught me language; and my profit on’t

Is, I know how to curse"

Time for more promised Jacobean theatrics. Not old man Caliban, whose quote starts this section – we’ll come back to him. Rather we look to The Revenger’s Tragedy, written by Thomas Middleton (or Cyril Tourner, if you want to take up cudgels on his behalf) in 1606. The play enjoyed something of a revival in the 1980s; its satirical, cynical, not to say violent nature reflecting some of the moods swirling around “Thatcher’s Britain”. The kissing of a poisoned skull by The Duke, for example, prettified to resemble a mystery lover – one of the play’s key scenes – is a concept of towering 80s artifice, but then so was the maintenance of Kajagoogoo’s hair. The play’s violent emotions and heightened sense of opposites, reality versus duplicity, perverted ideas of justice, personal worth and station, all seem to find an echo in some of Porcupine’s incredible folio of lyrics; which are possibly Ian McCulloch’s most personal and – at times – wild and lupine.

Mac maybe sensed his band was ripe for a kicking: the tedious concerns of the music press in getting their pound of flesh playing more and more in his mind. He was armouring himself and the band to ward off accusations of being the “shall” in pot-ten-tial and the “suck” in “cess”, to quote album track ‘Clay’. This is the period where, according to the band’s old press officer, Mick Houghton, Ian McCulloch became the lead actor, Mac The Mouth. Even with that in mind, McCulloch’s lyrics on Porcupine are a berserker’s vapourtrail: a Norse-Scots-Scouse self-mythology that’s swallowed a dictionary, bevvied up incantations to himself and a world that appears around him like a magic lantern show. The sometimes precocious, earnest nature of his lyrics on Heaven Up Here (such as on ‘The Disease’ or ‘No Dark Things’), youthful declamations that essentially looked outwards from a stage, suddenly become inward facing, taken to the darkroom and given a “reet proper” acidic dunking. They reappear overexposed and blown up; biting and burning and hot to the touch. This is a world of mirrors created by the singer’s own imaginary logic.

The use of specific literary tricks abounds, such as chiasmus: a form of repetition where the same words, phrases, or ideas are reversed and repeated; possibly to highlight or even negate a point, often by turning these words on their heads, in slightly different contexts. Porcupine is riddled with phrases that become incantations: possibly best experienced in two terrific uptempo tracks, ‘Clay’ and ‘Ripeness’. On ‘Clay’, Mac asks: “Am I the half of half-and-half / Or am I the half that’s whole?”, deciding that, “I’ve got to be one with all my halves” but then, in the next verse, asks his other self: “Are you the heavy half / Of the lighter me / Are you the ready part / Of the lighter me?” Set over the dizzying, crashing backdrop of the music and the relentless charge of the rhythm section, the track becomes an initiation into a cult of outsider personality. Glum, bedroom-bound teens the length and breadth of the United Kingdom sucked this up as manna from heaven.

Gnomic riddles, alliteration, repetition, it’s all there. Then there are elements that draw less on the traditions of poetic composition than ludic pop-folk rhymes: why Mac felt compelled to sing, “I am all Will Hay / You are all Bob Todd”, on an early take of the album’s most dazed and confused track, ‘Gods Will Be Gods’, is anyone’s guess.

This all sounds very clever and at times funny, but McCulloch’s lyrics openly chronicle his insecurities. One can sympathise with Mac, who admitted he found singing investigations into the darkest, opposing sides of his character over complicated music extremely trying. Like the decorated skull in The Revenger’s Tragedy, the message of Porcupine can be cast as a public mask that deceives both its maker and warns those around not to get too close.

Maybe Mac’s intuition was sound: Porcupine has something that gets under people’s skin. Something that’s maybe “too fucking raga”, to quote Julian Cope in Repossessed describing sitting in his Tamworth Festung, watching Echo play ‘The Cutter’ on TOTP. Mark Edward Smith felt enough reverberations in his psychic nose to mention the Bunnymen disparagingly, alongside King Crimson, in his opening remarks to Fall shows in early 1983. His incantations may be pitched to protect The Fall from what he saw as the “same old joke again every night”. These remarks may hark back to those Jacobean takes on jealousy, intrigue and revenge: the duel played out with words.

A Thousand Twangling Instruments

Even Mick Houghton felt the need to show some steel: “Porcupine was the first time they questioned what they were doing, almost to the point of wondering why they were doing it at all. That tension is what makes it such a great album, even though I’d probably need a gun to my head to listen to it again.” These kinds of borderline put-downs among the inner circle often crop up when Porcupine is mentioned: one example is a typical Bunnymen interview for Melody Maker, to mark the release of their 1987 self-titled “Grey” album. Here, Les, Will and Mac routinely slag off Porcupine – as well as their new record. Par for the course in sardonic Bunnymen world. But Porcupine is fantastic: it contains two of their greatest and most well-loved singles, ‘The Cutter’ and ‘The Back of Love’, and brilliant album tracks such as “lost single”, ‘Heads Will Roll’; a true slice of hard rocking psychedelia that is built on a fantastical undercarriage of a “thousand twangling instruments”, to quote Caliban. ‘In Bluer Skies’ is the first portent of what was coming with Ocean Rain, namely, the whimsical, trickster side of the band, who here seem to enjoy the mild uplift in the instrumentation like a warm bath after a winter walk.

The reason Porcupine has traditionally got a bad rap is probably down to two tracks that follow each other on the B-side of the record: ‘Higher Hell’ and ‘Gods Will Be Gods’. Deep dives into the psyche, and presenting themselves as (inchoate) existential musical tracts, they can be confusing, unless you totally commit to their otherworldly weirdness. But then the sounds on both tracks can also be revelatory; flashes of guitar or terrific bass lines act as the sun shining through the accumulated muck on a dirty bus window. ‘Clay’ and ‘Ripeness’ are also fabulous, fast-moving soundscapes that would also not be out of place in a film score: the chasmic guitar parts adding to the emotion and mystery. Then there’s the two-part title track, akin to some heavy gothic romantic symphony, a foghorn of sound with its mix of weird percussion, soulful piano parts and vast armies of ghostly guitars. The Cure would also channel a similar spirit on their 1989 album, Disintegration. This is grand, theatrical music, an uncompromising and public noise that straddles the pop and art worlds and fails, magnificently. A mission and an admission of confusion and frailty: like Tintin holding onto Captain Haddock’s rope in Tintin In Tibet.

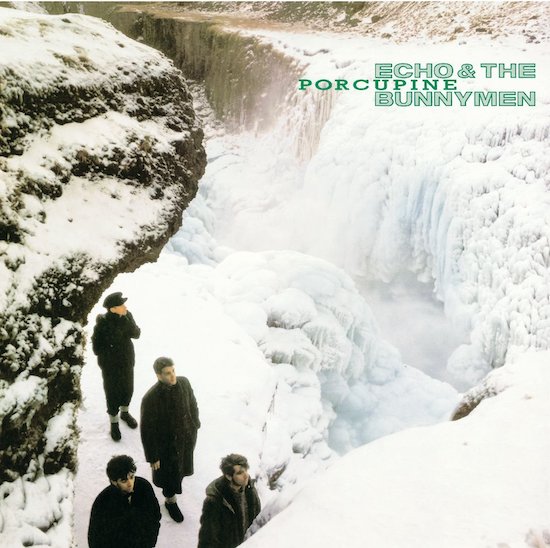

Talking of glacial-themed heroics in pop culture, after the whole thing was finished in late 1982, Drummond sent the Bunnymen and a team including Bill Butt, Martyn Atkins and Brian Griffin to Iceland to film what became An Atlas Adventure, and shoot the album cover. Around the same time, a wild and frayed Teardrop Explodes toured Australia and New Zealand. If you believe the myth (and why shouldn’t you), both these occurrences gave Drummond licence to stand in the middle of Mathew Street in Liverpool on what he believed to be a sacred ley line, while grasping a statue of Carl Jung: all to attain what he hoped would be his True Genius. The two bands, unaware of their roles as familiars in an act of Prospero-style cultural witchcraft, stumbled around obliviously, doing what bands do, separated by attitude, not to mention numerous lines of latitude and longitude. The Bunnymen team – freezing their collective nads off (with Mac in wholly unsuitable felt shoes) – gingerly trod along a narrow ledge high above the Gullfoss waterfalls, which partially freezes during winter, in an attempt to capture their Bunnygod spirit for the album cover. One slip: certain death.

Gullfoss waterfall, photographed by Martyn Atkins and annotated by Will Sergeant

Act Three, Scene One. A midweek “vinyl night” in my local pub, the brilliant WW in Leiden, where various middle aged types, fraying at the seams, just like the LPs and singles they bring along, try to impress the passing juice drinker. If only that callous twentysomething, now bent over their phone, would “truly understand” Mott The Hoople… That kind of thing. I too, try to persuade young minds to look further than the pixelated fleshpot of Tinder, and throw on the B-side of Echo & The Bunnymen’s ‘A Promise’ single, ‘Broke My Neck’. I’m accosted by Jan, a true believer in the power of vinyl records. Tanned like a walnut and bedecked in Lycra, Jan likes to play Adrian Belew solo records, Thai film scores and Dutch chanson; often all at once. Like those whose lives are solely obsessed with collecting records, he’s a tiny bit out there. “Bunnymen! What’s your favourite out of the first four?” I mention that for me it’s a toss-up between Ocean Rain and Heaven up Here. Jan immediately crouches into what can only be described as a kung-fu battle stance. “Why do people say this? You are so wrong, it’s Porcupine! Porcupine!” Jan may have a point.

Some records just exist, brooding in a collection, waiting for a new part to play. Ian McCulloch may have sensed this with his lines on the title track, “A change of skin/ Will shed the tail/ Hung on the wall/ For use again” At some point, Athena’s owl – her accompanying animal and symbol of knowledge, wisdom, perspicacity and erudition – will perch on your shoulder and whisper that holding on to the concerns of times past is a dead end, la. Look what happened to Marvin the Paranoid Android: blessed with all those brains, yet still with hurts to heal. “The first ten million years were the worst, and the second ten million years, they were the worst too. The third ten million I didn’t enjoy at all. After that I went into a bit of a decline.”

In my mind Porcupine is the album that found its voice smack in the middle of the Britain of 1983, a fractious and confused time in society and pop music; a cultural landscape that was marked by unabashed and naked hedonism, a preening and arch self-referential smugness and a mounting anger at the state of things. Just like now, in fact.