I was just reading Lori Majewski and Jonathan Bernstein’s recent book Mad World, an often enjoyable look back at smash songs by ‘new wave’ acts as defined in a Mid-Atlantic way. In the section on OMD’s ‘If You Leave’ the authors talk about the division between ‘OMD Phase 1’ and ‘Phase 2’, between the UK hit phase and the US one. They also ended up interviewing a singer from another Liverpool band of note at the time, about a song from an album thirty years old this year called ‘The Killing Moon’ – and the same division vis-a-vis OMD could be applied to Echo And The Bunnymen, to a degree.

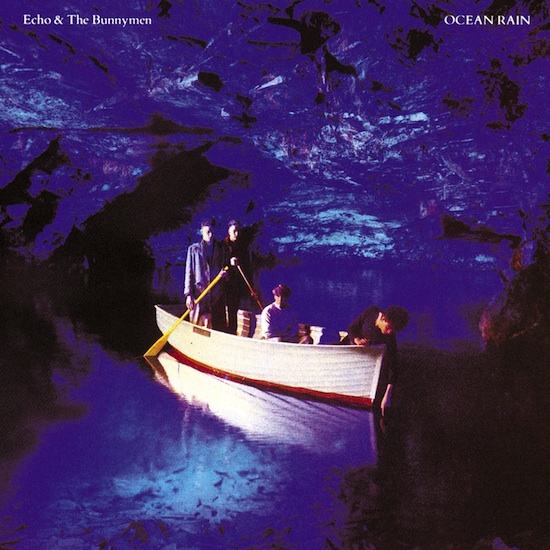

Phase 1 – those four albums that built them up to chart appearances and obsession at home, the ones Bill Drummond says were always part of a plan down to their cover art (and even if they weren’t I wouldn’t see them any other way myself; I still need full posters of all these on a wall somewhere).

Phase 2 – Doors cover versions for a Stateside movie about pseudopunk vampires, band brittleness, kinda sorta further American breakthroughs, breakups. Then tragedy beyond anything OMD experienced; their story has never been the same since.

So looking back at Ocean Rain over three decades is to look back, from an American perspective at least, via retrospective discovery. There were fans here at the time, there were always fans – among musicians alone during said moment, there was Michael Ivins of the Flaming Lips, Chris Eckman of the Walkabouts, future members of Pavement, more besides – but I only first heard of them a couple of years later thanks to another soundtrack: Pretty In Pink. And that was mostly because I couldn’t get the guitar riff from ‘Bring On The Dancing Horses’ out of my head as I heard it shimmering through my sister’s closed bedroom door. Looking through books like Chris Adams’s indispensable band history Turquoise Days, seeing the relevant Ocean Rain quotes, the stories, the ads – especially the slogan “The Greatest Album Ever Made”, a tagline that’s so perfectly over the top that I’m surprised Kanye West hasn’t taken it yet – gives me a sense of what was up, but only that. Compared to the monster albums to be that ended up breaking out commercially the rest of that decade, especially those by Ian McCulloch’s bete noire, one Bono Vox, and his associates, Ocean Rain’s relative chart success was strong but not Enormodome qualifying. That was only a dreamy fantasy; ‘Mac The Mouth’ material.

But the dreamy fantasy is, of course, the album itself. A fantasy made flesh, but not fleshly, at least not in the way one would normally imagine. Spiritual to an intense degree, but similarly not the rote language of praise per se. Take a song which is scraping and chopping then suddenly lush in sound and back again, and call it ‘Thorn of Crowns’, you might go, "Well, fine, it’s a joke, but somebody thinks a lot of themselves, perhaps." Have lyrics in said song that go "Cucumber, cabbage, cauliflower", all with stuttered opening letters, you might go, "I’ll… see myself out." Only to have McCulloch doubtless snark back at you for missing both the reaching up and out of the song and the piss-taking along the way while Will Sergeant smirks a touch. (Les Pattinson, I don’t know, though he likely would be quietly amused either way, while Pete de Freitas might go, “Don’t worry, man, I understand it. I don’t understand Ian, but…” and so forth. A fantasy band reaction in its own right, granted.)

Ocean Rain as presented at the time bespoke ‘quality’, the type of thing that is regularly applied these days to albums that are purportedly recorded on wood-hewn tablets and locally sourced by beardy men pining for the days of cholera. So having that applied to something else is a useful corrective, though admittedly there’s an idea of going back to roots-as-such going on in an all around entertainer way from the band members’ own childhoods. It was recorded in Paris with orchestrations (even if an overindulgent McCulloch so enjoyed the local beverages that he ended up doing most of the vocals back in the UK), brushes on the drums, acoustic guitars everywhere if not solely so. It’s reacting to the present, though – the band’s own past, the groups it was associated with despite not wanting to be, other up and coming artists from further distance as well they felt much more akin to (Sergeant was apparently taken with the skeletal arrangements of the Violent Femmes’ brilliant self-titled debut, and if the connections aren’t obvious on first blush, they seem more so on the second). It’s not simply haunting the footsteps of 1968 Scott Walker – heck, if anything, those bits about the cucumbers and cauliflowers sound like something Walker’d do in later decades instead, if not actually turn said objects into instruments. Ocean Rain in the end was its own strange, spiky (if not indeed thorny) beast.

‘The Killing Moon’ was the lead single and probably still towers over everything else the band’s done in the end; certainly McCulloch has said as much and it’s hard to gainsay him, when it all clicks just so. It’s the start of the second side of the original album, more or less the centrepiece or a centrepiece, and it has so much going on that even on a relisten after so many listenings something about it still feels surprising. Maybe this time it’s the groove – Pattinson holding it down and keeping it moving so what could be a drunken sway under the streetlights walking home becomes a ballet under sparkling stars – as much as anything else. McCulloch’s soon to come solo debut later that year, a one-off take on the Kurt Weill classic ‘September Song’, was always an indulgence, but really, he’d already written its equal, the type of thing that will long outlive its times in turn.

But it’s the strum and strings of ‘Silver’ which kick off everything, and the opening lines are “Swung from a chandelier,” and everything trips and flows so perfectly that it feels like it just happened, a romantic dream that’s actually Romantic, poetry in motion. It never feels dour, depressed, the raincoat brigade or an overcorrection to it – it just, well, feels like the titular precipitation, something that gleams, that invites. Sergeant’s solo could be made of diamonds, de Freitas’s rolling roil of drums carries and propels, never pounds, it’s far too active for genteel contemplation. It’s a spring song, more than might be guessed, or spring evenings perhaps, the nights getting longer and the moods getting more sly and more sweet at the same moment, partying with the blind sailors and prison jailers.

‘Seven Seas’, meanwhile, is not only a fine song title for an album named after oceans but is another example of a lot going on without fully calling attention to itself. Chimes lead into the chorus, piano fills in the emphasis in a way that sounds like it could be from a 4AD release around that time, swimming through reverb. “Burning my bridges and smashing my mirrors” is the kind of turn-it-around sentiment on commonplace turns of phrase that not only deny the purported lessons the phrases teach but makes the denial something to celebrate beyond simply going “To hell with this!,” and it’s done with what can only be called panache.

If the songs that weren’t the singles sometimes seem that they never could have been, they always manage to sound perfectly in place with the ones that were – the hits in comparison weren’t upfront or unique, just more immediately of notice. There’s the elegant strut of ‘Nocturnal Me’, pitching things softer and more focused on the chorus instead of the reverse, or the way ‘My Kingdom’ has each verse line suddenly climb up then ease down, then builds each chorus to a sudden thrilling peak. ‘Crystal Days’ and its descending guitar line that showcases the psych freak always at the heart of Sergeant’s playing, broken up by de Freitas on the break with a gleeful but always tuneful clatter, a percussive melody, might be my sleeper favourite this time around. Ask me again next time, maybe it’s ‘The Yo-Yo Man’. I like it when an album is an embarrassment of riches and can’t make me obviously decide, when it shouldn’t to start with.

Then there was the title track. The only way it could end, really, and what an image. Water on water, something that felt like it had to be at night even if it wasn’t. When you talk about a wash of sound, it’s easy to think of digital delay and haze, an overpowering electronic whoosh and roar. But it’s the reverse here on all levels – stillness, focus, contemplation, space everywhere, notes played with deliberation. Everything could theoretically be howling around you, the lyrics mention hurricanes bringing heavy storms on a ship in the middle of nowhere, but the band has found a calm centre where you look out on it all instead, and maybe the rain isn’t a storm but a perfect layering curtain stretching to the horizon. When McCulloch first sings “Screaming from beneath the waves” the violence is a shock in contrast to the music, when he concludes by stretching out “the waaaaaaves!” over and again as the strings rise up around him before coming to a final, quick verse and then silence, it’s a spotlight moment that takes everyone in.

Look at that cover photo again and there’s the band in a grotto, the bluest of water, the steadiest of boats. I like to think of this album as starting there and then ending in the middle of that ocean, a progression to wherever the band wants to go, maybe to the edge of the world where the water falls off into infinity. A dreamy fantasy? Call it that without regrets. That’s precisely why Ocean Rain works now, still, and will continue. Of course it’s a greatest album ever made, why can’t it be, and I’m happy to see thrive beyond whatever phase.