It’s ridiculous, when you think about it, that people have such a massive range of ways to spend their finite lives, some constructive, some less so, but that staring at a games console screen should be one of the most popular of those choices. Shrink that down still further, and the amount of time and money that gamers spend on murdering computer-generated images in first person shooter games is astounding. What’s the point?

Well, look at the basic premise of the first person shooter game. It’s simple and it’s a lot of fun. You look down the barrel of a gun and shoot the adversaries that jump out in front of you, clearing levels, solving problems and defeating bosses until the final stage is completed. The experience can approach splatter-movie levels of gore, depending on the game’s storyline and target audience. A verb, to ‘gib’ – pronounced ‘jib’ as it’s derived tastefully from ‘giblets’ – was even coined to describe the act of blowing someone to pieces, accompanied by lesser or greater amounts of blood. (At the same time, it should be noted that there are others which avoid that aesthetic entirely and which you could safely let your four-year-old play.)

A company called Id Software was responsible for kickstarting the format. The first ever FPS game was Id’s Wolfenstein 3D from 1992, an MS-DOS product that was a laughably primitive experience in terms of graphics and sounds, but not all that different in playing style from its many modern descendents. The player navigated a labyrinth, murdering Nazi soldiers and their attack dogs, while grainy graphics, cheesy sounds and an eight-bit soundtrack generated an atmosphere, of sorts. Give or take some improved graphics, playing speed and overall intensity, that’s basically how we’re still doing it today – and not without criticism.

The second FPS was the shareware and mail-order game Doom, also released for MS-DOS by Id in 1993, which was then amped up a year later with the appearance of a commercially-sold sequel, Doom II: Hell On Earth, and two subsequent expansion packs. At that point, a step-change occurred which is the reason for this 25th anniversary analysis. Simply put, from 1994 onwards, murdering monsters on a screen for enjoyment became a major earner.

The first two Dooms were a revelation, which is a bit of a misnomer considering their unholy content. The idea was that the player was up against demons from hell, ranging from common-or-garden zombies, via fireball-throwing Imps, up the scale of toughness via Revenants and Hell Knights to the end-of-level bosses, Arachnotrons, Cyberdemons, Guardians Of Hell and so on, all very familiar to the average Terry Pratchett reader.

Geeky and unthreatening as this may have been to anyone of adult mind, the game inevitably received more than its fair share of attention and mud-slinging when it emerged that the perpetrators of the 1999 Columbine High School massacre were keen Doom fans, even playing the game on a private server. Just in case it needs reiterating yet again, Doom didn’t kill all those poor kids. Seriously disturbed, heavily armed teenagers killed them.

The games’ primary architect, and one of Id’s co-founders, was John Romero, the self-confessed gaming nerd to end all gaming nerds. He and his team knew perfectly well that their buyers loved the gore aspect of the games, and deliberately exploited that element for maximum thrills. And why not? He and his colleagues did so well out of Doom that they went and bought Ferraris with suitcases of cash, as recounted in an excellent book, Masters Of Doom.

The question, then and now, is why people love violent games like Doom so much. I’ve written extensively about aggressive music and films, and the appeal of the stuff for people of generally sane mind is exactly the same when it comes to games. The starting-point in all cases is that the material is disturbing. How could it not be? In Doom, you routinely eviscerate and execute a whole range of enemies in a terrifyingly dangerous environment. The day that a proper VR version of the Doom games appears will also be the day it gets properly scary.

The contradiction is that the intense focus of the FPS game is both stimulating and soothing for the player, a phenomenon that was noted and analysed as the games industry matured. None other than the New Yorker observed the calming qualities of first person shooters a while back, labelling them ‘a virtual environment that maximizes a player’s potential to attain a state that the psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi calls ‘flow’ – ‘a condition of absolute presence and happiness.’

There’s also the fatal attraction factor. What else might lurk around the corner? How far will game designers go to shock us? Let’s have a look and see, is the obvious answer from many of us. We like being spooked. Jump-scares make you laugh, once you’ve got over the shock.

On that note, Id Software really flexed its muscles with the truly magnificent Doom 3, released in 2004 – a decade after Doom II, and several generations further along in gaming terms. Now suitable for faster PCs and the first Xbox, the game stepped away from pure carnage into horror. Thanks to a zippy new game engine, Id Tech 4, which included expressionist pools of light, enhanced shadowing, advanced texture mapping and whatnot, the graphics were now close to filmic in nature, the occasional amusing polygonal head aside. Chris Vrenna of Nine Inch Nails created the music, a combination of spooky synth washes and industrial-metal riffs, which gave it some credibility among the kids who bought the game. Creatives from all sides were now paying attention.

More importantly, there was an actual storyline… of sorts. Although, in retrospect, the tale – in which a space marine goes to Mars, and then to hell, and back again – could have been written by the average 14-year-old school kid, it was dynamic enough to grip the player. Crucially, it included a long, tense buildup before the point where hell is (literally) let loose.

The gameplay was more intelligent, too. Far from mindlessly blasting away at an array of fiendish attackers, you were required to navigate a maze in almost total darkness, flinching every time you walked past an alcove or doorway. Although the player becomes nonsensically overpowered as the game progresses, the adversaries – specifically the higher-level demons such as the Arch-Vile and Hell Knight – could kill you very quickly, so you were also very vulnerable. It was a totally immersive experience which gamers bought into wholesale, with only Valve Corporation’s competing Half-Life 2, also released in 2004, the only FPS which came close in terms of richness and intensity. Even a wholly awful 2005 film adaptation couldn’t derail the Doom phenomenon at this point.

The really clever bit was this. After a nice few years of raking in the cash from Doom 3, which sold 3.5 million copies in its first three years, Id decided to release the game’s source code to the public in 2011. This wasn’t purely motivated by generosity, you can safely assume. Id had noted the rise of a game-modding community, which had adapted the first two Dooms into versions of their own – notably Brutal Doom, a ridiculously over-the-top bloodbath of a game – and knew that the opportunity to do the same with the much darker, more complex Doom 3 would only increase the game’s profile. This it did, with multiple mods available for download all over the web, many of which can still be enjoyed on YouTube.

This effectively broke the fourth wall in the gaming world. By the mid to late 2000s, a huge number of Doom modders were connected by efficient broadband and powerful, games-dedicated computers. Speed-run challenges in which gamers strove to outperform each other became the norm across all games, not just dear old Doom. By 2013 or so, the original franchise had been relegated to the status of an aged relative at a family gathering: influential in its day, but now outperformed by huge-selling FPS games such as Call Of Duty. By then the biggest franchise of all, Grand Theft Auto, had sold an unnerving 280 million units: sure, GTA is a first person driver rather than a first person shooter, but it bears many of Doom‘s uncompromising hallmarks, notably unflinching aggression on the part of the player.

People missed Doom, though, and not just the most recent, horror-focused third variant but the old, blow-’em-away style of Doom and Doom II. Fun and unsophisticated while still wholly playable, the old games from 1993 to 1996 – which might as well have been the Middle Ages in comparison to the modern gaming era – were often revisited by nostalgists. A great example of this retrograde view came in 2013 when an interviewer from the gaming website IGN and John Romero played through the first Doom together – it’s worth watching in its entirety for Romero’s insights into that far-off era.

Inevitably, demand for a fourth Doom was there. A sequel was in development by 2011, but suffered from all sorts of political issues. In 2012 Id remastered and reissued Doom 3 as the BFG Edition, a package named after the game’s famous ultimate weapon the Big Fucking Gun. It was a smart way of monetising an old game, but at the same it time it offered value, containing the first two Dooms and a couple of extra missions. This kept fans at bay for a while until the new game, just called Doom, came out in 2016.

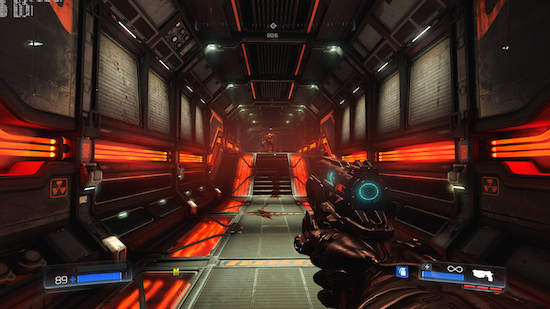

Having been suckered in by the genuinely spine-crawling tensions of Doom 3, I was keen to play the new version. Like most fans of the franchise, I loved the new textures, beefed-up weapons and the glossy, amphetamine feel of the gameplay, but was it intimidating? Not at all – it was a laugh. Spacious, well-lit arenas replaced the claustrophobic, haunted corridors of Doom 3, and the monsters were about as frightening as the cast of a Marvel film. It appears that the days of Doom pushing the player out of their comfort zone are over, despite the promise of a sequel, Doom: Eternal on the way as you read this.

Still, what a run the franchise had. Twenty-five years after the industry started to make serious money out of FPS shooters, and broke down a lot of cultural barriers in doing so, as well as making players and their parents soil their drawers, it’s all gone safe again. Something will come along and shake things up again, though. Something always does.