Exuding rage, wit, colour, funk, antagonism, style, attitude, love and hate like steam rising from a grate, Spike Lee’s Do The Right Thing, released 30 Summers ago in 1989 and set in the troubled Bedford Stuyvesant district in Brooklyn, feels on initial impact like a hip hop movie. In 1989, hip hop was at a critical juncture. De La Soul had just released 3ft High And Rising, ushering in a mooted Daisy Age which in its mellow yellow vibe chimed in with the smiley culture of the acid house scene breaking out across the Atlantic in the UK and Europe.

1988, however, had also seen NWA put out Straight Outta Compton, the first salvo of gangsta rap. And then there was Public Enemy, altogether less laid back, altogether more political, at the height of their powers. Do The Right Thing’s tear a new asshole in the concept of Hollywood opening credits. Strafed by the deep rumble of passing traffic, Public Enemy’s ‘Fight The Power’ crash lands, with Rosie Perez in a variety of costumes performing a street dance that’s muscular, combative, aggressively beautiful, dares you to objectify her. When Chuck D shouts “1989”, it still feels today contemporary, on a dangerous cusp, the century on the point of overheating.

‘Fight The Power’ recurs throughout, booming out of the beatbox of Radio Raheem (Bill Nunn), cutting ominously through the film’s fabric. That said, Do The Right Thing runs deeper than the merely recent. At one point, Samuel L Jackson’s local resident DJ Mister Senor Love Daddy, reels off a list of great African American artists – among them, Ray Charles, McCoy Tyner, Anita Baker, Branford Marsalis, James Brown, Oliver Nelson, Janet Jackson, Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, Stevie Wonder, Funkadelic, Sara Vaughan, Keith Sweat – a rich and still electric, teeming heritage of musicians across a range of styles of which hip hop is but the latest upshot.

This is reflected in the cast also, with poet, playwright and civil rights activist Ossie Davis starring as the impecunious Da Mayor, alongside his real-life wife Ruby Dee, as creatively and politically active as Davis. She plays Mother Sister, who surveys the street from her brownstone window, with a sardonic and disapproving eye, especially for the daytime drunk Mayor. Their scenes are soundtracked by a warm, jazzy score, composed by Spike Lee’s father Bill; indeed, many of the early scenes in the movie are coated by an idyllic patina that reminds of 1950s cinema, despite the run-down state of the neighbourhood.

The next generation down is represented by three middle aged guys, Sweet Dick Willie (played by the late Robin Harris), ML and Coconut Sid (Frankie Faison, later Burrell in The Wire) who spend their sedentary days bickering, gassing and wisecracking. Genial good-for-nothings they may be but they function as one of the multiple Greek choruses in the film (alongside Jackson’s DJ and a gaggle of excitable younger youths featuring a young Martin Lawrence), observing and commenting on goings-on, rather than being active participants.

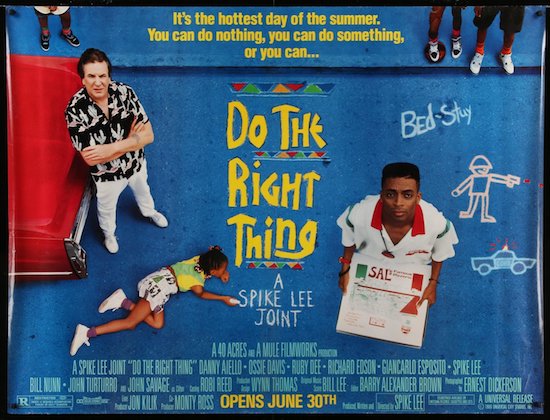

Lee depicts the district not as a gang zone but as a place where people of all races live and get on with their lives, know each other by name, trade with one another. This positive vibe, however, is countered by an undercurrent of racial tension. Lee spares no one but is fair to all. Victims of racism are also its perpetrators. (A montage shows the various groups taking turns to abuse one another to camera). There is deep resentment among the African-Americans to the recently arrived Koreans who have established a corner shop in a previously boarded up property, a resentment they express in anti-Asian epithets and exhortations to “learn goddamn English”. There’s a young white yuppy played by John Savage, the first sign of a coming gentrification, who finds himself confronted by black locals for moving into their neighbourhood. The then 32 year old Lee himself plays Mookie, 25, but looking about 17, a pizza delivery guy with a somewhat languid and indifferent approach to his job. He works for Sal (Danny Aiello), longtime Italian-American proprietor of a pizza parlour. His elder son Pino hates the location, and, despite his love of Prince and Michael Jordan is openly and acutely racist.

Sal seems a great deal more tolerant. He slips Da Mayor a dollar a day to sweep up outside the shop and has a crush on Mookie’s sister, much to Mookie’s disgust. He reproves his elder son, reminding them that African-Americans are his customers. However, when local would-be activist Buggin’ Out (Giancarlo Esposito, later Gus Fring in Breaking Bad) loudly chides Sal for having no pictures of African-Americans in his restaurant, it clearly touches a nerve, as well as triggering the fatal climax to the movie. Sal’s walls are packed with framed pictures of among others, Robert DeNiro, Sophia Loren, Al Pacino, Frank Sinatra. It’s clear that for him, sticking in the neighbourhood is not merely out of tolerance but cultural defiance, clinging to a past in which Italian-Americans, not African-Americans, defined the identity of Noo Yoik. And, in the film’s climax, he reveals distinctly racist bones in his body in a confrontation with Radio Raheem in which he calls him a “black cocksucker”.

That said, despite the militancy of the film, Lee idealises no one, least of all Buggin’ Out, considered something of a jerk even by his fellow African-Americans, and who is mocked when he tries to organise a boycott of Sal’s (“You should boycott that barber who fucked up your damn head!”). Meanwhile, he puts his own character in question when Mookie, as tensions rise, puts a dustbin through his employer’s window. The film ends on an ambivalent note regarding the usefulness of violence, with contrasting quotes from Martin Luther King and Malcolm X.

The police are the true villains of the film, however, as its tragic outcome attests. First, cruising through the district, mouthing the words, “What a waste” at local residents, for the mere crime of sitting and doing nothing, and then in the final arrest sequence. Lee had been inspired to write Do The Right Thing by the story of Eleanor Bumpurs, an elderly, disabled African-American woman shot to death in 1984 by a police officer during an attempted eviction. The officer was later acquitted. It was one of several such deaths throughout the 1980s which inflamed tensions between African-Americans and the police.

There had been fears at the time that the film itself would incite young African-Americans to riot, which Lee rightly dismissed as racist nonsense, implying that blacks were inherently incapable of self-control. However, the acquittal of the officers filmed clearly beating up construction worker Rodney King would in 1992 lead to the Los Angeles riots; Do The Right Thing was prophetic in this respect.

That said, the century did not take quite the revolutionary turn anticipated by the movie, or by Public Enemy. Mainstream hip hop went down the gangsta route; amoral, materialistic, reflecting the relatively untroubled, opulent ease of the 1990s. Public Enemy fell by the wayside; and, despite hip hop being consumed in the 90s by a largely white audience, it depicted a world in which whites barely figured at all, certainly not as oppressors. In hip hop, if not the actual world, the beef was principally black on black. Meanwhile, the Bedford-Stuyvesant area in which Do The Right Thing is set continued to become slowly gentrified, in a similar manner to East London. More and more John Savages moved into the area; hipsterisation continues to this day.

None of this pacification, however, solved anything. In one scene in Do The Right Thing, Sal jokingly discusses his real estate ambitions with two police officers, one of whom retorts by calling him “Trump”. Do The Right Thing is packed with small part players who would go onto bigger things; Trump, sadly, was one of them. He has put racism right back on the agenda. Meanwhile, the Black Lives Matter campaign, its message tragically reinforced by the sheer number of cops killing unarmed African-Americans. Things changed after 1989 in America, but fundamental evils remained unaddressed. The issues raised with a searing urgency by Spike Lee 30 years ago burn just as hard today.