It may seem almost churlish, but it’s hard to overlook the fact that Nas and DJ Shadow make for fitting labelmates. Towering presences in hip hop history, the pair remain most feted for debut albums that catalysed their respective cultural moments in the mid-1990s; and both, to an extent, have remained trapped within the viewfinder many fans and critics use to look back on those epochal and undeniably important records. And yet, just as Nas has gone on to make records that are at least as good, if not better, than Illmatic only to invariably find audiences lazily comparing them unfavourably to his debut, so too has Shadow seemingly been condemned to find his latest work held up for evaluation against Endtroducing, and almost always – and just as inaccurately – be considered inferior to that hugely important yet reflexively overhyped LP.

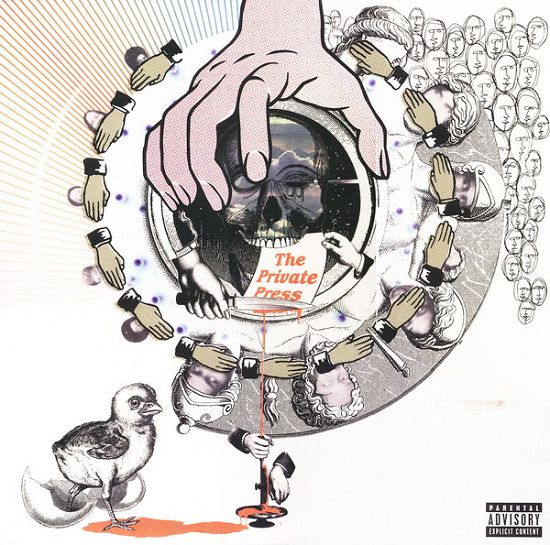

The Private Press, Shadow’s second album, was the first of his releases to suffer the by now customary "it’s good, but it’s not Endtroducing" critical reception. We do this with our cultural heroes in a way that defies logic and common sense. Surely those who valued Shadow’s work on his debut would want to hear where this technically and compositionally gifted musician wanted to go next – not condemn him to forever retread his first exploratory steps? That The Private Press was not simply Endtroducing Part Two was one of the best things about it, yet the majority of the less-than-gobsmacked reviews that greeted its release 20 years ago focused on how it failed to follow the same path. It’s as if, despite claiming to praise artists for their creativity and originality, we then wish to place tight limits on how far from their original vision we are willing to let them go. Fortunately for posterity, and for anyone with an open mind and a willingness to engage, Shadow wasn’t going to let himself be chained to anyone’s pre- (or mis-) conceptions.

"I think when I sat down to do another solo record and had total control over what I wanted to say, I wanted to offer the listener as many chances as possible to latch on to something that might mean something to them," he told me when we spoke ahead of the album’s release in 2002. "Whether it be something they can all sit around and laugh about, or something they can sit around to and relate to in their own world. If music is communication, then that’s what I’m trying to get to the heart of." These goals are lofty, but he achieved them with room to spare.

A Post-it note in his workspace during the extended gestation of the record read "non-linear.” Too academic to stand a chance of becoming the album’s title, this was nevertheless a guiding principle behind a record that may mine an already well-established seam of beat-laden melancholia, but which found Shadow aiming at a suite of music that spoke to a far wider spectrum of human experience. There’s joy, anger, bravado, introspection, and even one or two well-turned jokes. Sampled voices echo down the decades and bring an air of timelessness and an almost haunted presence to some moments while a rap written for ‘Mashing On The Motorway’ locates the album in an ongoing present. Each track tries something new, yet each adds to a cohesive whole. And while he was anxious to avoid making a concept album, the repeated use of privately pressed records for extended parts of the source material gives a humanising unity of purpose to an album which, at times, found Shadow working as cerebrally and calculatedly as he ever has done – and to quite startling effect.

There are, of course, moments where the LP recalls his debut, where Shadow makes tracks that sound like nobody else and that utilised a sonic approach that had become a distinctive trademark even then. Two of them arrive early on the record – ‘Fixed Income’, with its "slow, trashy drum break" which was "kind of familiar territory for me," as he put it; and ‘Giving Up The Ghost’, a looping, extended moodscape which was the only piece that existed in any form before Shadow began consciously working on The Private Press, having been written for a Michael Mann film. Yet even as both would have felt familiar to fans of the first LP, both also took that established sound somewhere new. Simply in terms of instrumentation these songs were doing something unusual. ‘…Ghost’s central, cyclical riff comes from, possibly, a thumb piano (further echoes, perhaps, of Nas) while ‘Fixed Income’ switches leads between what sound like orchestral strings, a cor anglais and a zither (though it’s probably a guitar).

What connects these pieces to his previous work is the diversity of the many sample sources, but what is new, different and dramatically deepened is the interweaving of those samples into wholly new musical cloth, in ways that are seamless and compositionally extraordinary. It’s one thing to have an ear for a sample and to spot its potential as a motif to be used in a different context, but how does anyone hear two fragments as disparate and as culturally distant as, say, an untitled 1978 recording by new-age guitarist William Eaton, and a 1970 rock reworking of Gilbert & Sullivan’s The Pirates Of Penzance by the otherwise unrecorded band Spindrift, and even think that they might form part of the same whole – never mind make them sound as if their original creators would never have wished them to be heard apart?

A key ingredient that helps to differentiate the tracks here from what had gone before is the reliance – not total, but extensive – on privately pressed records for many of the samples used. Today, with reissue labels excavating every micro-niche in the history of recorded sound, and the phenomenon of digital ubiquity promising instantaneous worldwide access to even the most obscure recordings, such a guiding principle for making sample-based music might seem irrelevant. Indeed, the very idea of a privately pressed record may mean nothing in the smartphone age, where apps and decent microphones come close to putting a reasonably high-spec demo studio in most people’s pockets. But in 2002, with the record business in the early throes of digital disruption and always-on full-fat broadband still a pipe dream for many, privately pressed records had an aura and a meaning that felt different and, to an artist like Shadow, would have presented both a source of inspiration and an irresistible challenge. At this point in his career, to focus on them as the primary providers of colour in his sonic palette was a choice that still felt like it mattered. And it is undeniable that it enriched the record Shadow ended up making.

"I was trying to take a starting-over approach," he told me of the initial creative impulse. "It was just me making demos again. And it felt good. It just really felt like I had pressed ‘reset’ and I was starting clean. I was getting a lot of that energy from these [privately pressed] records, and I put them around my workspace, especially if they had pictures. They were just so earnest. They had nothing to lose. Many of them weren’t good at all, but some of them were amazing, and what they all are is charming. They’re sweet in some way. They’re so starry eyed, in a sense: so ambitious but so troubled – because they hadn’t a prayer, you know?"

It wasn’t all wilful obscurity. Several samples come from major label releases, one or two even by household names. The intro to the dazzling ‘You Can’t Go Home Again’ (based around an obscure but contested funk break, Cut Chemist had found it too, and Shadow knew he needed to work fast to put his stamp on it first) comes from a track on Simon & Garfunkel’s Bridge Over Troubled Water. Amid the kind of lost and forgotten fragments of sound that together constitute ‘Right Thing / GDMFSOB’ no less than Leonard Nimoy, as Spock, is roped in for the vocal hook "pure energy". These occasional glimpses of the familiar help root the record in a relatable reality; keep its imagination and exuberant enjoyment of the extraordinary tethered to something we can still grab hold of. It’s a record of often profound strangenesses, but one that Shadow never allows to fly off into the abstract. Rather than consider these instances as rule-bending by someone cheating at his own challenge, therefore, we should consider them carefully placed cornerstones without which the rest of this edifice could never stand.

The most obvious – and most extreme – examples of privately pressed pieces that ended up on the record are the Recordio Discs that wound up in the opening and closing ‘Letter From Home’ tracks. One-off recordings pressed onto cardboard and designed to be sent by their maker to their single recipient by post, these were anomalies even among the obscurity-obsessed crate-digger community Shadow was almost an adjunct professor of at the turn of the century. Not really records, they didn’t turn up in second hand record shops, and when people did unearth them, they’d often be hiding alongside personal letters or private mementoes in the kind of places that ended up with the unwanted portions of house-clearance sales. Today we would perhaps interpret them as aural selfies, albeit ones created by a generation that still retained a rote form of formality when sending messages that email and SMS has all but obliterated: Novella Johnson signs her audio postcard, and puts her address at the top, like a letter. (Go online and you discover even the street she was "writing" from no longer exists; the past is forever being rewritten, and not just by DJs making sonic collages.)

But the most extreme use of a private-press record on the album is the two bars from the 1976 B-side ‘Plenty Action’ by Soft Touch which makes up almost all of the album’s astonishing centrepiece, ‘Monosyllabik’. For all that he didn’t want to make a concept album, Shadow was not averse to allowing a concept to set a challenge that he had to push himself to meet head on. He’d already set a few rules here: while, working on U.N.K.L.E.’s Psyence Fiction, he had allowed himself the leeway of using musicians to play things when sampling wasn’t going to work, for The Private Press he refused to use any musical ingredients that didn’t come from previously released records. The hugely influential Brainfreeze mix, made with Cut Chemist in 1999, found the pair only allowing themselves to use 7" 45rpm singles. Its all-45 follow-up, Product Placement, incorporated numerous 7"s released to promote some product or other, and recreated a fans’ favourite sequence from Brainfreeze using different versions of the same tracks in a kind of "cover version" of part of the earlier mix.

The delight in accomplishing such absurdly, arbitrarily and unnecessarily difficult tasks was clear: so it was little surprise that there would be challenge he would set for himself here, and that it would be of another order of magnitude altogether. With the notable exception of its introductory cry of "What you gon’ do now?", which comes from a 1977 United Artists release by The Whitney Family, on ‘Monosyllabik’ Shadow forced himself to make an entire track using only sounds he could make out of the first two bars of that privately pressed late-period funk 45. He began by cutting the two bars into 32 pieces, then set about attacking them in the studio, using only outboard gear and analogue equipment – no plug-ins or computers. Microphones were set up to record the sound being played in different ways from different speakers, then fed back through the system and spat out in new shapes, each to be reforged, sifted, rearranged and reconstructed in a process he compared to stop-motion animation.

Yet what should surprise us is how an entirely cerebral and intellectual conceit resulted in such an astonishing and potent piece of music. If you didn’t know it was all from one place, you’d be hard pressed to tell, as Shadow polishes, twists, distends and distorts his source material to turn it into something that sounds, at different points, subterranean, alien, cyborg, industrial, spacey, explosive, intimate, meticulously detailed and hugely, supersizedly massive. It’s a record that on its own justifies the investment you might make in a decent hi-fi: not just a series of amazing sounds, it’s structured in three dimensions – bass pulsing like a heartbeat from deep, low and way back within the soundstage as high-end slashes of sound fizz like agitated wasps from left to right and back again. Beyond collage, beyond music production, ‘Monosyllabik’ is a piece of sound sculpture. Like a sonnet or a haiku its formal restrictions forced its maker to transcend all limitations and succeeds on a level that surely could not have been reached had he given himself fewer or looser rules to adhere to.

"I had never heard of a song being done, in my theatre of references, where the entire song was one sample. That was the kick-start of the album for me, because it was so different from what I was used to doing," he recalled. "Usually I’m very cognisant of trying to make music that’s from the heart and has a lot of soul, and with this one I was doing the opposite. I knew I only wanted to do it on one song. I would do six seconds a day. At the end of every day I’d be going upstairs and telling my wife ‘Damn, this song is kicking my ass!’ I’d keep hitting walls. And what made it so challenging for me is that in the past what I’d do is just look for more samples, but I didn’t have that luxury with this song. Any sound I wanted to use, I had to make. It was unique."

The record continues to echo down Shadow’s discography. The use of sincere but lost voices continued on 2006’s The Outsider, with ‘This Time (I’m Gonna Try It My Way)’ – released as a single – built around a vocal track he found in a radio-station clearance sale, on an unmarked white-label acetate; royalties were paid into an escrow account in case the artist and/or writer could ever be identified. The wonderful ‘Six Days’, in which the original Colonel Bagshot song is given a delicate, evocative new setting, examined themes of relationships as warfare (and vice versa) that would fuel what has become his biggest hit, the 2016 collaboration with Run The Jewels, ‘Nobody Speak’. And in 2019, on the magnificent Our Pathetic Age, he came arguably as close as he ever has to a piece of sonic sculpture to rival ‘Monosyllabik’ with ‘Juggernaut’, an astonishing construction of bass, noise and portent. The Outsider and Our Pathetic Age received a mixed response, as did The Less You Know, The Better, where Shadow’s sincere – and abundantly necessary – attempts at undercutting internet snark by highlighting its inanity in the sleeve art and the promotional campaign led to, of course, a surfeit of internet snark being channelled his way. This stuff is never easy.

Non-linear is right. Progress – in art, in culture, politics and history – is never as simple as today’s participants building constructively on the positive achievements of their predecessors, rejecting what has failed and only ever improving on the ongoing design. Like Nas, Shadow could probably have gone on repeating the moves he’d found worked with audiences on his debut, and scored some acclaim and had significant sales – but that would have short-changed his audience and ruined him as a creative force. Instead he’s kept on pushing ahead, aiming to keep a step in front of expectations but always aware that he might be moving too far, too fast, and in too unexpected a direction to keep everyone on side. This was the first step along that road, and is important for that reason – but The Private Press remains an engaging, moving, beautiful and incisively inclusive record; a masterpiece that rewards each and every listen.