There’s music that illuminates your past with the detailed clarity of a flare, or a flashbulb, lighting up moments of joy and discovery. There’s music that envelops the memory of who you were and what you loved, curling like warm smoke around those bygone years. And there’s music that jabs you out of such reveries and reminds you of things you dislike so strongly about the person you used to be that you prefer to pretend that person was someone else entirely.

This, for me, is an album in the third category.

I was going to add, “Through no fault of its own.” But hearing The Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy’s Hypocrisy Is The Greatest Luxury again, I’m not so sure. I think the blame may be shared, between my callowness and its appeal to that very trait. It’s hard – impossible – to separate, in my own response, what I was from what the record was. But revisiting the record, I owe it at least an effort to see past the former. When I wince, fairness demands I consider I wince at my failings and not those of the music.

Because it’s not without merits. I can still hear what captured me in the first place. The sense of encountering a musical union between two of my favourite artists, then and now, Gil Scott-Heron and Public Enemy. At the time, I thought – giddily infatuated as I was – that it combined the best of both. I now hear a record that falls, indeed stumbles and falls, somewhere between the two. Few pop acts have made rhetoric more persuasive than did Scott-Heron; none ever made polemic more thrilling than P.E. But polemic does not thrill by sloganeering, and rhetoric does not persuade by belaboured insistence. Hypocrisy Is The Greatest Luxury is full of both sloganeering and belaboured insistence. And now that I am, I hope, less susceptible to these things, it grates on me.

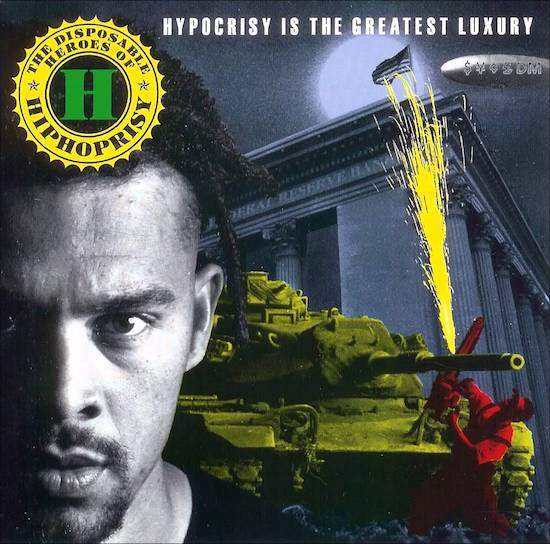

The Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy were a duo – almost, but not quite, in the way Wham! or Hall & Oates were a duo. Michael Franti wrote, co-programmed and co-arranged (with Mark Pistel), fronted and produced everything, Rono Tse attacked stuff. Specifically, he is credited with, “Angle Grinder, Tire Rims, Chains, Break Drums, Electronic Springs, Sheet Metal & Steel Drums”. When the band played live, his role came to the fore – they were, or so I recall, exciting as hell; but then, I can’t go back and check. What his contribution was to the record, it’s hard to know at this remove. Perhaps it was as much the idea of what he did as the fact of it: it helped define Hiphoprisy (or “the Disposables”, as I and other fans then called them, never guessing at this affectionate nickname’s inadvertent prescience) as industrial, confrontational, frictive, throwing off sparks.

I’ve come back to Hypocrisy Is The Greatest Luxury from time to time, most recently while looking for tracks to put on my iPod. (Yes, I still use an iPod, a practice which is not yet sufficiently archaic to be hip, but give it time.) And I found only one thing I could really stand to have shuffled in my direction: ‘Famous And Dandy (Like Amos ’n’ Andy)’. Franti’s sardonic dissection of rap as the latest form of showbiz to construct black male identity shows just how good Hiphoprisy had it in them to be: that rumbling industrial backing track, Franti in his best Chuck D mode (Hank Shocklee’s description of Chuck as “the voice of God” emerging from “a thunderstorm of sound” wouldn’t be too far off here), and a handful of killer lines – in particular when Franti swaggers into his “flavor of the month” bit: “Holding our crotch/was the flavor of the month/Bitch this Bitch that/was the flavor of the month/Being a thug/was the flavor of the month/No to drugs/was the flavor of the month/Kangol/was the flavor of the month/Rope gold/was the flavor of the month/Adidas shoes/was the flavor of the month/Bashing Jews/was the flavor of the month/Gentrification/was the flavor of the month/Isolation/was the flavor of the month/My pockets so empty I can feel my testicles/’Cause I spent all my money on some plastic African necklaces/And I still don’t know what the colors mean. . . /RED BLACK AND GREEN.”

But Franti wasn’t coming from where P.E. did, nor from where Scott-Heron did. Not just geographically – his chief musical heroes were/are New Yorkers; Franti is from the Bay Area. Nor in terms of his background: of mixed ethnicity, he was raised by white adoptive parents. The giveaway lies in the plainest pastiche on the album: a cover of ‘California Über Alles’ done as a straight-up P.E. number. His combination of ‘Music And Politics’ – that being the title of the only track on the album which is not directly concerned with the latter – draws not its sound or its manner but most crucially its mindset from that San Francisco/Dead Kennedys/Alternative Tentacles axis. The point at which anarcho-punk’s circled “A” developed a magnetic attraction for the modes of thought that now characterise self-styled resistance movements of the Left – geo-politically and conspiratorially minded, anti-statist, coherent only in the sense they view any and all iterations and degrees of capitalism as equally corrupt and reprehensible – was the point at which Hiphoprisy arrived.

And there was no reason why this should have stopped Hypocrisy Is The Greatest Luxury being an amazing album. It didn’t stop Hypocrisy Is The Greatest Luxury being an amazing album. What stops Hypocrisy Is The Greatest Luxury being an amazing album isn’t what Franti had to say, but the way he had of saying it. It isn’t his voice. He was a powerful vocalist; he had the tone and timbre to rival his idols. It’s his lyrics. He wasn’t a rapper so much as he was a pamphleteer. If rap was “the black CNN”, Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy were a wordy, indignant protest newsletter.

The reason the album now makes me wince is not because I disagree with its politics (often as not I don’t), nor with its worldview, although I do, profoundly. As somebody who has observed close-up the difference between countries that have long-established democratic infrastructures and institutions, and those which do not, I rank these things among the very few I would consider taking up arms for, in defence against all comers no matter what their supposed political stripe. If you’re for the revolution, I’m against you; because – almost certainly unlike you, you grand romantic – I’ve seen what happens in and after it. This is a point that has seldom seemed more relevant than now, when the most crucial divide is not between left and right but between those who will stand up for democratic institutions no matter what, and those who will undermine them to get their way.

Yet, just as I’m an atheist and I can thrill to religious and spiritual music, so I know much of the greatest political pop is revolutionary in its nature, in its spirit, in its fervour. Also, I know it’s usually at its best when keeping it simple. Pop music can do a lot more heavy lifting than it gets credit for; what it isn’t good at it is carrying bulk. And this is what hobbles Hypocrisy Is The Greatest Luxury, in the end. Not whether it’s right or wrong; that is both subjective and incidental. But that it’s cumbersome. It’s so earnest and wholemeal, so densely packed with tangled vocabulary, that it undermines what would otherwise be its incendiary power. Ultimately, Hiphoprisy were the one thing no firebrands can afford to be: they were dull.

That took a bit of doing, giving what they had going for them. I would love to hear an instrumental version of the album, or at least its first half; sonically, it rather peters out during the second. But with that combination of industrial beats, high-tonnage bass, metallic noises and free jazz squalls – and with the masterful hand of Jack Dangers, of Meat Beat Manifesto, on the mixing console – it boasts one hell of a sound. And Franti has a voice to match. The problem, though, is audible from the off. When ‘Satanic Reverses’ jumps in – a spooky, choral monastic chant of “Hallelujah,” a hell-yeah kicker of a drumbeat, a blast of distorted trumpet, a stentorian baritone – the whole thing crackles. Then the baritone starts reeling off what sounds like the ‘Introduction To Global Affairs’ lecture you unwisely dragged your hungover carcass out of bed for too early in the afternoon: “In the Nineteen Hundred & Seventies/The OPEC nations began to dominate the world’s oil economy/In the Nineteen Hundred & Eighties Japan became the world’s number ONE economic power/In Nineteen Hundred & Eighty-Nine the nations of Eastern Europe attempted to restructure . . .”

It’s not that this stuff doesn’t matter. But it’s hardly, “In this corner with the 98/Subject of suckers, object of hate”, or “You are now about to witness the strength of street knowledge . . Straight outta Compton, crazy motherfucker named Ice Cube”, is it? And I don’t mean it should deal with what those rhymes do or say what they say. I mean that when you intend to melt everything down into red-hot revolutionary magma, even if you intend to get into some serious political analysis down the line, it might be best not kick off with something C-Span would consider a trifle dry.

This keeps happening. Lyrics are written to be heard, not read, so it can be misleading to see them transcribed. But I do the album no disservice when I say it is no less headache-inducing to hear than it is to read, say, “It’s tough to make a living when you’re an artist/It’s even tougher when you’re socially conscious/Careerism, opportunism/Can turn the politics into a cartoonism/Let’s not patronize or criticize/Let’s open the door and look inside/Pull the file on the state of denial” (‘Hypocrisy is the Greatest Luxury’), or, “Mother prepares a fruit salad to eat/sprayed with messed up pesticides/none have been tested for health effects on the side . . . Meanwhile in the backyard,/father lights up a barbecue fire/and he sizzles hormone injected meat/on top of a toxic source of heat/He becomes light headed as the toxins easily meet/with the lite beer in his head/and he glances to the portable television set/from his eyes he wipes the double vision sweat . . .” (‘Everyday Life Has Become a Health Risk’). And not headache-inducing in the way you want an apocalyptic industrial rap record to be.

Hiphoprisy’s signature tune, ‘Television, The Drug Of The Nation’ – which as a single was the first thing of theirs many of us heard – is also the most overtly Scott-Heron-esque thing on the album. And it’s telling that the Scott-Heron song it evokes is, ‘The Revolution Will Not Be Televised’. If someone knows only one Scott-Heron song, that’s probably it; and like many equivalent recordings by great artists (‘Imagine’, ‘Blowin’ In The Wind’, ‘Suzanne’, ‘I Just Called To Say I Love You’), it does no justice to his oeuvre. It’s a list song; and while it’s a superior one, it has more in common with ‘It’s The End Of The World As We Know It (And I Feel Fine)’ and ‘We Didn’t Start The Fire’ than with the supple, nuanced work Scott-Heron would go on to produce. Suppleness and nuance are not qualities Hiphoprisy possessed, either. Nor would the lack of them have mattered had Franti not always striven to make things more complicated than this music could withstand.

The human heart is pop’s great subject; that does not mean it must be pop’s only subject. It is very easy to make bad pop about politics, perhaps easier than about anything else, but it would be a pity if that put artists off trying. It’s creditable – admirable, even – that Franti tackled so much on this album: homophobic violence, the first Iraq war, his own knotted sense of identity, the socio-economic status of black Americans, plenty more. To really get into the meat of these issues would require books, or at least essays; to encapsulate the sense of such an issue into a pop song would require brevity, the knack of making a complex idea feel simple – something for which Curtis Mayfield, for example, possessed a magnificent gift. Franti landed somewhere between the two – songs that felt like essays, but in their efforts at complexity wound up seeming not simple but simplistic.

On the rather drab final track, ‘Water Pistol Man’, Franti sings rather than speaks or raps. It offered a clue to what he would do next: Spearhead, the kind of stoneground, dreary, funkless funk band beloved of white Bob Marley fans who go to festivals with “Earth” in the name, to hear music they consider consciousness-raising, although any other listener is liable to lose theirs altogether. Perhaps Spearhead was where Franti realised his true artistic vision; the same vision that prevented Hypocrisy Is The Greatest Luxury turning out as the musical cordite it so readily could have been. It’s not that Franti compromised or betrayed his considerable talent; it’s that he was all too faithful to it, where a producer or co-writer might have helped him refine it.

But how much of this harsh verdict pertains to Franti, and how much to me disowning a part of my younger self? Here’s how I sort that one out. It’s a political pop record that you would probably have to think was right as right can be to love it. And while it embarrasses me that I was so eager to fall for it, to buy into a worldview I now consider reductive and potentially dangerous, I would define a great political pop record as one that moves you whether you agree with it or not. Public Enemy were the group who made “Bashing Jews . . . the flavor of the month” (although when isn’t it?); of whose leader it was justly said he never met a conspiracy theory he didn’t like. Yet they were and remain the greatest rock & roll band I ever saw or heard. Their work, their presence, has not dimmed an iota in my life and my imagination. If the opposite is true of Hypocrisy Is The Greatest Luxury, it’s not just because I’ve changed. It’s because it isn’t powerful enough to survive such a change in a listener.