In 1984, George Orwell has Winston Smith overhear one of the anonymous proles sing a song described thus: "The tune had been haunting London for weeks past. It was one of countless similar songs published for the benefit of the proles by a sub-section of the Music Department. The words of these songs were composed without any human intervention whatever on an instrument known as a versificator." The only quoted lyrics:

"It was only a ‘opeless fancy,

It passed like an Ipril dye,

But a look an’ a word an’ the dreams they stirred,

They ‘ave stolen my ‘eart a wye!"

The implication is mechanized social control, diversion from truth and reality, silly love songs, and not a little generalized snobbishness. One has to wonder what Orwell might have thought of Depeche Mode in 1984 when Cold War propaganda was still thick in the air. In musical terms there was a critical environment where too often ‘real’ instruments were seen to have more validity than anything made with electronics which was supposedly being MTV pop for the ignorant and fashionistas. In this Depeche Mode were an all-electronic band with its own songs haunting London and elsewhere included this as a lyric on its fourth album, following crisp pulses and hi-hat recreations, a snaky bass part and a distorted woodwind feeling of a melody:

"Come on and lay with me

Come on and lie to me

Tell me you love me

Say I’m the only one"

Or further in the song:

"Truth is a word

That’s lost its meaning

The truth has become

Merely half-truth

So lie to me

Like they do it in the factory

Make me think

That at the end of the day

Some great reward

Will be coming my way."

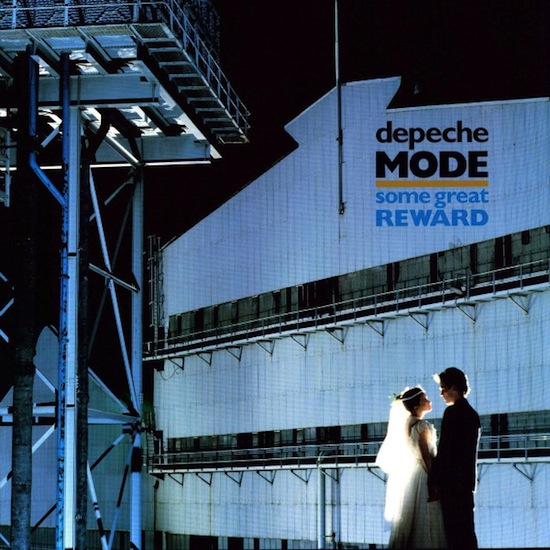

The great thing about Martin Gore as a lyricist is that he reduces so much to blunt imagery for it to work as a hook. No, really, it IS great. It’s a knack, a talent. It’s not always successful and he’d be the first to agree with that, but if you ever wanted to know why Depeche Mode succeeds, or rather one of the key reasons, it’s not just that he would write that lyric, it’s that he would write that opening set of four lines, laden with romantic/classic song imagery, and then go ahead and call it ‘Lie To Me’ anyway, foregrounding the moment that blows it all up. And then take another line in the song, make it the album title, and end up with the third in a series of great cover photographs via Brian Griffin, a bride and groom backlit in front of a very grey factory indeed. Sure you can analyze it all to bits from there, drawing on everything from Marx to the Gang of Four (the band, in this case), but again, that’s Depeche’s knack – you almost don’t need to. THERE it is. And it’s been put together brilliantly.

Some Great Reward was Depeche’s fourth album in as many years, the culmination point of one phase before yet another phase in the remainder of the eighties as the band slowly but surely became one of the biggest bands on the planet, getting up nearly everyone’s noses along the way and still pissing people off now just for existing even as they’ve become relaxed elder statesmen. Stepping back, hearing this album fresh for what it was rather than what it further pointed towards, turns memories into new appreciations. Because this is one ridiculously rich album, an industrial pop fusion of dreams, shot through with more subtlety than it’s given credit for, sequenced perfectly and in the end so accomplished that it’s no surprise Depeche shifted gears in the end for Black Celebration to create another landmark instead. Why rest on your laurels, especially when you’re young?

Depeche’s youth really is the key here still, the amiably geeky/wannabe flash of Essex kids on the make still there but just a little older now, Gore’s angst dividing into desperation and dreaminess and bitter contempt, Dave Gahan still some years away from singing lessons but able to use his baritone to match all appropriate moods, a self-contained boyband playing to its strengths in the most unexpected ways. Alan Wilder was well en route towards being one of the late eighties’ best pop arrangers, period, while the production team of Mute boss Daniel Miller and John Foxx assistant Gareth Jones, coming off their fine work on the previous year’s Construction Time Again, upped themselves further. And if confidence bred confidence everyone had to feel pretty well chuffed by the time Some Great Reward came out thanks to a lead single some months before that had blown through the ceiling.

‘People Are People’, in retrospect, takes a place for Depeche Mode that matches ‘Creep’ for Radiohead – the breakout hit early on (if a little later for Depeche), the song that established their name well beyond their home country (it went number one in West Germany, then became their first top twenty single in America a year later), the song that after a while the bands in question just wanted to ignore and leave behind them, however powerful it was for listeners at the time. It was how I first heard about the group, though in a weird indirect fashion – I vaguely remember seeing a live clip of the song from their American tour on MTV after moving back to California from New York in 1985, thinking it was an odd band name and noting Gore’s massed blonde hair more than anything else. But it was catchy, relentlessly so, and that was point – it was STUPID catchy.

In both senses of the word. Depeche haven’t played the song live since 1988 and are quite content about that, Gore writing off this particular lyrical exercise as a misstep not worth repeating. I wouldn’t say it’s down with the near contemporary Culture Club single ‘The War Song’ in terms of "Uh, am I really hearing this?" but it is a little off, a nursery rhyme with a little ultraviolence, where there’s nothing wrong at all with the actual sentiment, just how it comes across. Thing is, EVERYTHING else about the song, everything, is jaw-dropping genius. Depeche had already heard and figured out a way to transmogrify Gore’s beloved glam rock of his youth via industrial music’s metallic frenzy, Einstürzende Neubaten in particular, and the blasting electro coming out of New York and elsewhere – check out Construction Time Again‘s ‘Everything Counts’, especially the long version – but ‘People Are People’ put it all together in an arrangement that really did sound like a factory coming to life, busting out moves, stomping all before it by the time the last relentless beats kick in. It’s almost overstuffed with clatter and clangs, a sample collage programmed and played as music that rivals Hank Shocklee’s own soon to come work – and then on top of that, however goofily well meaning the lyric might be, it’s delivered with immediate singalong impact, both Gahan and Gore at their then best, harmonizing, then trading off verse and bridge and back again. Gore later cited classic doo-wop as one of his own sources of inspiration for those vocal tradeoffs here and elsewhere, further evidence of just how well he knew his 20th century pop, and just that one song itself was more legitimately heavy than most hard rock or heavy metal at the time. Yet as ever too many people just went "No guitars? A nice beat and you can dance to it? TEENAGERS enjoy it? NOT REAL," and, at least in America, adding on additional charming ‘limey synth fags’ complaints as they went, went back to talking about horrible new records from classic rock burnouts nobody actually cared about, the sole, unshared and unshareable virtues of punk rock, and/or how Bruce Springsteen was the only real musician. (And if you’re still like that, sucks to be you.)

If Some Great Reward had been nothing but a variety of ‘People Are People’-styled songs after another, it would still be a hell of a shock-of-the-new moment for that time, but thankfully Depeche had shown even from the Vince Clarke-led start that everything from slow ballads to high speed dancing was on the agenda. Songs like ‘Stories Of Old’, taking images of courtly love and smashing them out of desperation, and ‘If You Want’, Wilder’s last major direct songwriting contribution, split the difference between the extremes, a little stronger energy, a little calm. Meanwhile opening track ‘Something To Do’ is ‘just’ another song like ‘People Are People’ to a degree, with plenty of its own tricks and fillips like the strident electronic brass bit during the breaks, the gurgling burble of an opening sample sounding queasily biologic, the piano underpinning the arrangement for full impact. But ‘Master And Servant’ twisted everything around again – as direct as ‘People Are People’ lyrically but far more sinuous and unsettling in impact. Again Gore has the knack: the inspiration may have been extreme sex clubs in Berlin where they were recording, but the end result distills Bataille and Foucault almost without trying, a perfect opening vocal tradeoff of "It’s a lot like life" serving as both introductory hook and mocking commentary, a surrender from the get-go so why not embrace it to the full? And instead of ‘People Are People”s compacted crunch there’s a looser swing at the same velocity, tones setting the stage, screeches ripping across main melody lines along with shouts, gentle croonings of "Come on…" betraying just a little of the nervous/trying-too-hard figure Gore in particular was at this time with his black leather and fingernail polish.

Then again that nervous try-hard approach that was also part of a big point – Gore’s secretly affectionate nature, or at least his all-too-perfect shy boy act, as encapsulated in his singing. With Gahan taking the lead on the hyperactive singles, becoming ever more of a crowd-working frontman as he went, Gore’s understated approach became perfectly suited as a lead for the ballads and the deep cuts scattered throughout Depeche’s time. With a purer singing voice as such, soothing instead of amping up, it not only gave Depeche a perfect internal vocal contrast but an expanded palette overall – as much a dude approach to singing as Gahan’s swagger, say, but not as immediately lounge lizard as Bryan Ferry’s arch approach, more slightly ruined choirboy who can’t get certain thoughts out of his head no matter how hard he prays. He only takes the lead twice on Some Great Reward and the first, ‘It Doesn’t Matter’, plays out as a slippery tangle of nervous synth jitters, understated clangs and calmer melodies on the verses before a lovely glam-derived descend on the chorus. It’s a fine moment, but ‘Somebody’ – famously or infamously recorded by Gore in studio without a stitch of clothing on – that’s something else.

A friend once said that he figured every woman in Southern California of a certain age had this song as their all time Depeche favorite to this day. Another friend went to the trouble of going down on one knee and singing this song to his girlfriend – a trained singer like himself – in hopes she would accept his proposal of marriage. (It did, BTW, and they’re still together well over a decade later.) ‘Somebody’ for me is one of those songs that works beyond its context just that little bit more, and also one of those moments where Gore moves just a little beyond what became his well established themes – it clicked, and resonated, the gentle piano and the restrained, distant samples, the album’s quietest overall arrangement, supporting his killer vocal. The twist of sour in the sweet – lines like "Though my views may be wrong/They might even be perverted" and "Though things like this make me sick/In a case like this I’ll get away with it" – reminds me of one of Gore’s glam heroes Sparks and their jaundiced view of the human creature. But by coming from the other direction, heart over snark, yet leaving just a hint of it in, the smallest touch of metacriticism of love songs but beautifully sung, the result is suddenly profound. Maybe only a few later songs like Ultra‘s ‘Home’ and especially Playing The Angel‘s Gahan-sung ‘Precious’, the latter a love song to children in a family riven by divorce, reflecting his own then-recently failed marriage, has Gore aiming for such emotional nakedness to match the physical and, indeed, getting away with it.

‘Somebody’ was released as part of a double A-side for the album’s final single, probably because they wanted to hedge their bets a bit. Because ‘Blasphemous Rumours’ is something else again. It’s the album ender and it points the way to Black Celebration in more ways than one, lyrically and musically. Not entirely – if anything, Black Celebration is when you remove ‘Blasphemous Rumours”s cheery sounding chorus (and that’s definitely cheery only on a musical level), add in even darker moods and samples and then head straight to hell. Which, considering that ‘Blasphemous Rumours’ begins with a distant minimal melody looped and chimed, big slow grinding bashes and beats, what sounds like a spine being stretched and disassembled and then the return of the burbling sample from the start of the album and more besides, is saying something.

And lyrically? I’ll quote two friends in an exchange from a few years back: "’Blasphemous Rumours’ is stupid too, in that adolescent Show of Depth way." "I remember thinking this song was SO DEEP when I was 13, so mission accomplished." And for all that’s understandable criticism from a safe distance, again, that’s exactly the thing with Gore, reducing problems from the dawn of humanity and related philosophical questions down to a distilled mass, welding it to a melody, and the next thing anyone knows it’s four years later and a Rose Bowl audience of tens of thousands of fanatics are chanting the words back at the band. It might not work later in life for most but it sure worked for a lot of folks then, and there’s always another batch of 13 year olds, and when the song is about teenage suicide attempts, rediscovering faith and then dying in a car accident anyway, it’s pitch perfect melodrama for any kind of high school trauma setting. Add in a dollop of a chorus about God’s "sick sense of humour/and when I die I expect to find him laughing", and you got it, Depth Shown in a big and blunt way, a meat cleaver or a mace rather than anything resembling a rapier. But it still works, and I’ll take it over whatever Richard Dawkins has said lately.

All that and there’s so much quiet detail throughout the album, the way samples shape a beat or a bass line or a melody, echoing off the vocals, how the vocals themselves are treated or used differently from song to song, sometimes crystalline, other times distanced and reverb-laden, and always, always, ALWAYS going for the hook. Whatever it is, wherever it appears, everything hangs off of it, or them, and what could have been admired for abilities with new technologies fused with older tricks was subsumed, intentionally, with fully conscious thought, behind the fact that Gore as the main mind kept reeling off a series of songs to start with that allowed themselves to be transformed without ever disappearing. (And hey, no knocking Andrew Fletcher in all this – he may always be the quiet man on the creative front, but as the band’s then de facto manager and built-in focus group for whether a song worked or not, they couldn’t’ve done better for themselves if they tried.)

So for all that Some Great Reward was the key step for what was to come for Depeche, for all that you could easily hear where Trent Reznor went ‘whoa’ at some point in the mid-eighties, for all that the sheer gifts that the band had in abundance kept returning throughout, aided and abetted by the right coproducers and engineers, it wasn’t enough for some in the end, whether rockist blowhards or experimental extremists or some other group again. It was too poppy, it was too easy, it was too obvious, it was too silly, it was too electronic, it was too English, and so many kept raging and raging and raging against the band and pointed to an album like this and a lead single like that as an example. But music, and art, has its own sick sense of humor, and it’s clear who all has laughed last and loudest.