According to his family, Martin Gore was a shy, introverted child. But that was then. By his mid-twenties, he had taken to wearing rubber fetish gear and singing ‘A Question Of Lust’ (containing the couplet "My weaknesses / You know each and every one") to hundreds of thousands of people with his band Depeche Mode. It’s always the quiet ones…

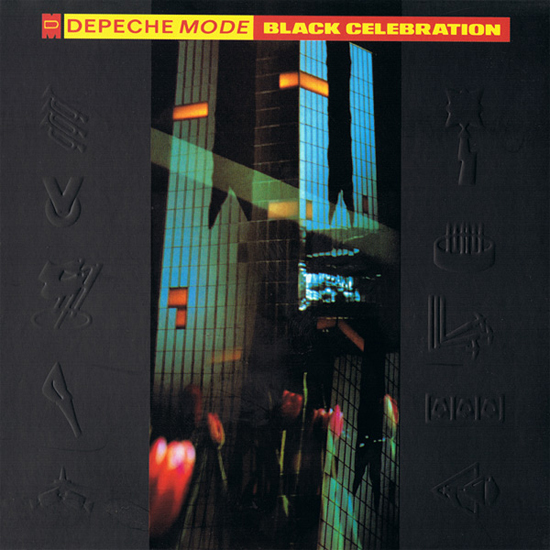

Artistically, Gore had come a long way by 1986. Black Celebration is a fine and kinky record that signaled a transition in Depeche Mode’s career; they became darker, sonically more adventurous and sweetly subversive. "If you call yourself a pop band," remarked Gore at the time, "you can get away with a lot more." It was the record on which Gore’s burgeoning writing skills thrust him deeper into the epicentre of an already successful group. He provided lead vocals on (an unprecedented) four tracks, including the angst-infected ‘World Full Of Nothing’ and the fabulous dirge of ‘A Question Of Lust’. But more than that, Black Celebration was perhaps a turning point for the band in the UK. While America seemed to already ‘get’ Depeche Mode (they succeeded as a new-wave pop band who could also fit snugly next to REM on a college radio playlist), they still possessed the whiff of ‘guilty pleasure’ in their home country. Black Celebration winkled a legion of Mode fans out of the closet.

Five years earlier, Depeche Mode had lost their principal songwriter, Vince Clarke. As one of Britain’s most prolific hit-makers, Clarke’s were big shoes to fill – he already had written the synth-pop classics ‘New Life’ and ‘Just Can’t Get Enough’ for the Mode, and would go on to further success with Yazoo, The Assembly and Erasure. Gore stepped up to take the main writing duties and if, perhaps, it took him a couple of albums to truly find a groove, Black Celebration was the point that the Basildon quartet became very, very interesting.

Martin Gore was undergoing an intense period of personal change in 1985-86. He had moved to Berlin, and enjoyed the freedom and creativity of the art scene. He experimented in fashion – with a particular penchant for women’s clothes – and was intrigued by sex clubs and the S&M scene. He could be wildly foppish – claiming to be inspired by "Camus, Kafka and Brecht" – but was rooted in the mind-numbing nature of the everyday struggle. He was keen that Black Celebration was not seen as a self-indulgent, depressive record – the title track itself being a call to rejoice the end of another humdrum day.

And it is not to say that Gore hadn’t been pivotal to the evolution of Depeche Mode during the intervening years that followed Clarke’s departure. Both 1983’s Construction Time Again and the following year’s Some Great Reward generated more hits and strengthened their fanbase in Europe and America. However, even the big singles suffered from clunky sixth-form poetry (see ‘People Are People’ and ‘Everything Counts’) or mildly embarrassing displays of sexuality, as on the clumsy S&M metaphors of ‘Master And Servant’. While Gore’s writing, coupled with keyboardist Alan Wilder’s increasing influence, had taken the band away from their fluffy electro-pop beginnings, there was still an ungainliness about the Depeche Mode sound.

Black Celebration saw Depeche Mode step out of their ‘gangly teenager’ phase, even though the album was created in an extremely difficult period for the band. By late 1985, the newly-married Dave Gahan was sober and judgmental of Gore’s hedonistic Berlin lifestyle. The stop-gap single ‘It’s Called A Heart’ had been a weak offering and the band were unsure of their next musical step. When record company suits began to vet Gore’s embryonic new material, he "freaked out" and disappeared for a week, holing up with an old school exchange friend in rural northern Germany, complaining that "the business did my head right in." Gahan would later state that if Depeche Mode were ever to have split up "it would have been at the end of 1985."

The method of recording Black Celebration also shoveled on extra pressure. The album was produced by Mute’s Daniel Miller and Gareth Jones (who had worked with the band on previous albums) and recorded at London’s Westside studios and at Hansa in Berlin. Miller – inspired by German film director Werner Herzog’s idea of ‘living the art’ – suggested recording in one continuous session spanning four months, with no days off. While this undoubtedly added to the intense, claustrophobic feel to the songs, it left Jones emotionally shattered – "I’d never do anything like that again," he would later remark. Also, Alan Wilder was becoming progressively more proficient as the ‘studio techno-bod’ and began to muscle in on the role previously taken by Miller and Jones. Four months, no break, toes being trodden on – sounds like one long party.

The lead single for Black Celebration was ‘Stripped’. It’s an ominous and intriguing pop song – the lines "You’re breathing in fumes / I taste when we kiss" exude the opaque carnality typical of Gore’s lyrical style at that time. Sonically, ‘Stripped’ relies on the heavy use of samples to generate its metallic jaggedness – the song starts with a sample of the ignition from Gahan’s Porsche, while the backbone of the track is the splutter of an idling motorbike.

Wilder’s all-consuming and often tortuous quest for samples did create the Bladerunner-meets-techno vibe on the superb ‘Fly On The Windscreen – Final’. While Gahan intones that "Death is everywhere," the song squelches, burps and bleeps like a Synclavier set to apocalyptic mode. Sampling guru DJ Shadow quotes Black Celebration as one of his favourite ever albums, claiming the band gave him his "interest in synth music." Depeche Mode’s influence on electronic dance music is, perhaps, hugely underrated.

Arguably the best song on Black Celebration is the track that relies least on studio alchemy. ‘A Question Of Lust’ sees Martin Gore’s growing lyrical confidence explore the covert paranoia of sexual relationships. Over a distinctly conventional melody, Gore reveals his vulnerabilities – "I need to drink / More than you seem to think / Before I’m anyone’s." It’s a beautifully constructed song – Melody Maker called it the band’s "greatest moment."

Indeed, lyrically, Gore seemed at his best when exploring the more desperate elements of relationships and the tension between sex, trust and love. He claimed that "70 per cent of my songs are about sex," and the assertion seems to hold for Black Celebration, be it the promise of one last shag before obliteration on ‘Fly On The Windscreen – Final’ or the hopelessness of "She doesn’t trust him / But he will do" on the deceptively corrupt ‘World Full Of Nothing’. However, Gore struggled when his words veered away love and lust. The soap-boxing on ‘New Dress’ – which rallies against the nation’s obsession with Princess Diana’s latest fashion statement, set amid a backdrop of shocking news headlines ("Girl, 13, attacked with knife") – was delivered with the subtlety of a sonic boom.

The final single from Black Celebration was ‘A Question Of Time’. It is a fairly standard Depeche dance chugger (although apparently about a predatory male trying to corrupt a minor) and is more notable for its promotional video. It was the first time the band had worked with Dutch photographer Anton Corbijn (who had previously thought they were "sissies" and only agreed to the project because it allowed him to film in America). Corbijn would go onto produce many of Depeche Mode’s promo videos, including those for ‘Personal Jesus’ and the iconic ‘Enjoy The Silence’.

Black Celebration elevated Depeche Mode to arena-tour status in the UK, while cementing their popularity in America (where they partied their way through a 29-date tour). It also began the trio of career-defining albums including 1987’s Music For The Masses and the crossover, stadium-filler Violator (1990). This run of form perhaps captures the band’s musical zenith, before their subsequent output became bogged-down and fractured by Dave Gahan’s spiraling drug use. Martin Gore was central to this period of creative highs – the quiet, introspective boy had developed into a brutally honest and sonically expansive musician.

Originally published on March 4, 2011