By the time 1975 rolled around it was hard to escape the feeling that something, somewhere had gone wrong. The Vietnam War was still rumbling catastrophically on, beaming images of seemingly endless destruction into the homes of a by-now numbed populace. Between the ultimate failure of the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam and the fallout from Watergate scandal, reminders that the counterculture of 68 had failed to deliver the goods as promised, and was now so much soggy pudding, were unavoidable. For young, smart people with a conscience it was a bleak period. And so, as was its wont, science fiction evolved to provide a slew of novel dystopias for these young, smart, conscientious people to look forward to. Were they to suffer the tarsal claws and mandibles of hyper intelligent ants (Phase IV)? Or the sidearms of runaway cowboy robots (Westworld)? Or good old-fashioned nuclear annihilation (Chosen Survivors, Battle For The Planet Of The Apes)? Imagining ways for humanity to be supplanted, overthrown or just plain exterminated had become a national pastime by the middle of the ‘Me’ decade; dystopias, apocalypses and attendant wastelands were doing good business.

And if there was one film maker who knew all about good business it was Roger Corman, whose production company New World Pictures had already been selling drive-in frequenting teenagers their hopes and fears back to them for five years by this point. A master huckster, with a love for cinema very nearly the equal of his love for making money and a cheeky, rebellious spirit, Corman’s low budget, high thrills approach to film making had already gifted the world of cinema a clutch of classics that predated NWP including A Bucket Of Blood (1959), The Little Shop Of Horrors (1960), The Fall Of The House Of Usher (1960), The Trip (1967) and The Wild Angels (1966). His practice of hiring young, inexperienced (and therefore cheap) writers, directors and actors to helm his films helped kickstart the careers of Peter Bogdanovich, Jack Nicholson, John Sayles and Martin Scorsese. So, it was inevitable that the king of B movies would look around the desolate landscape of 1975 and try to think of a lucrative way to cash in on all that ennui. And it was the pre-release publicity for a forthcoming film called Rollerball, set in a corporate future in which violent sports are used to subjugate the public, that would show him the way to do it.

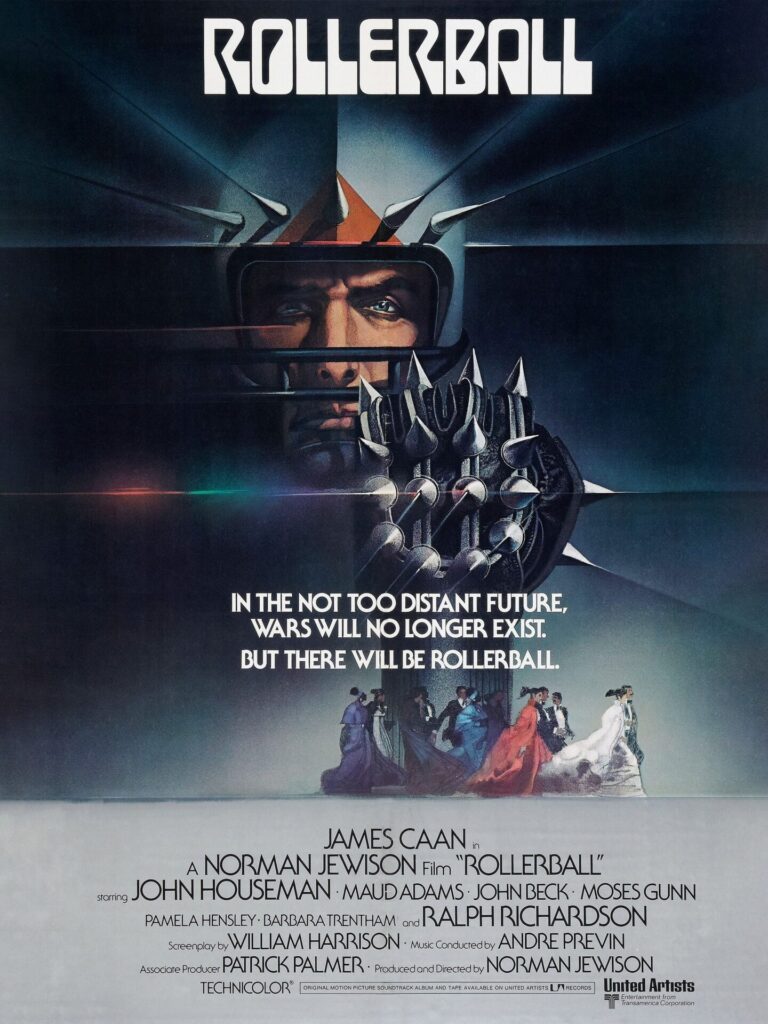

Always quick to chase a trend Corman reckoned that this brand of science fiction might be the next big thing and so set about creating a film to soak up some of the extra money that Rollerball might leave behind. If his project failed it was no matter as his productions did not cost much in the first place, but if Rollerball built a fanbase who wanted more of this type of… whatever-it-was? Well, that would mean money. And Roger Corman liked having fun with money. And so, as is often the case when a new high concept begins to infiltrate the public consciousness, the Violent Future Sport phenomena that was to move through movies, comics, TV and video games began with an outlier. Rollerball, released on 25 June 1975, despite being the first name most people would think of when asked to name this type of movie, and despite being one of the most aesthetically influential films of the 1970s, is closer in spirit to the brooding and malcontent dramas that had been popular a few years earlier; the brooding and malcontent dramas which would be put decisively to the mat by Rocky, with its stoical and uncomplicated hero, a year later.

Concerning a sports superstar’s dawning awareness that not all is right with the narcotically nullified dystopia he’s living in, Rollerball is undersold by a whispering James Caan performance. The film has an air of soporific anaesthesia that, while plot appropriate, sits at a difficult angle to the verité-tough sporting sequences that crash through it every now and then. Rollerball’s seeming lack of interest in aligning its separate parts hurts the film considerably. Despite some memorably eccentric supporting performances from John Houseman and Ralph Richardson, it never quite gets up on its skates. The problem is, it betrays its literary influence – it was adapted by screenwriter William Harrison from his own short story – by being in the tradition of self-important sci fi media satires such as Norman Spinrad’s tediously ‘of-its-time’ novel Bug Jack Barron, with its socially conscious edge blunted by its pompous, quasi-libertarian ‘one-good-man-against-the-whole-rotten-system’ plot. It’s ponderous, and more comfortably situated in the lineage of post-counterculture critique than the sci fi sports movies that came after it, its principal influence being expressed mostly in terms of futuristic aesthetics and bone splintering violence.

Because it was surely the violence that the audiences were turning out to see. The sport sequences in Rollerball are brutally impactful, with hard bodies in plastic armour sprawling into each other with a satisfying crunch, and a blood splattered, tooth-and-nail physicality. The game itself is barely comprehensible, there are motorbikes, roller skates and a chute that players have to shove a solid metal ball into, but it’s impossible to tell from the way the matches are filmed whether each side has its own goal or whether they’re all just furiously circling the wooden rink, jostling to stick the ball in the same hole. It doesn’t matter, mangled bodies hit the deck, people catch fire, jocks get brain damaged, and that’s clearly what the viewer was digging in 1975, because Rollerball was a hit to the tune of 6.2 million dollars, and if there’s one thing that 1970s cinema teaches us it’s that where there is success there is imitation.

But incredibly, Corman was so fast out of the traps in trying to imitate Rollerball that he actually beat the film to the mark. So quick was he to get his cash-in film on the burner, that Death Race 2000 – produced by him and directed by Paul Bartel – was out in cinemas by 27 April, crossing the finishing line some two months earlier than the film that inspired it. One result of this was it became the movie that did the most to define the philosophical tone of the Violent Future Sport phenomenon. Death Race 2000 set in stone a commitment to sneering defiance, Grand Guignol bloodletting and cynical dystopic satire, creating a hallmark for the way these stories were going to be told in the future and across many mediums.

Set in a fascistic America, years after the “world crash of ‘79” and focussing on a transcontinental road race in which points are earned by drivers who fatally plough into pedestrians, Death Race 2000 is Rollerball’s snotty-nosed kid brother. The Corman/Bartel vehicle ended up concerned with how much automotive destruction it could squeeze out of its sandpit budget than the smarty-pants intellectual explorations of its older/younger sibling. Corman was infamous for his quota based approach to film making, meaning that as long as the minimum amount of stuff that the audience actually wanted to see – bare boobs and exploding heads – was present and accounted for, film makers could, within reason, do as they liked. This approach bought him into conflict with Bartel, who envisioned the film as principally a broad satirical comedy, and by all accounts fought a breathless struggle to resist Corman’s exhortations to add more violence. To no avail as, being the guy in charge of the money, Corman simply shot a load of carnage and inserted it later, overriding Bartel completely. The result was yet more proof that the old art versus commerce argument was anything but simple. Death Race 2000 became a big hit, eventually becoming regarded as one of the cornerstone exploitation films of its period; the mix of slapstick violence and blacker-than-black comedy it presented proving enormously influential.

The cinematic equivalent of a giant extended middle finger mounted on the bonnet of a Dodge Challenger mowing down everything in its path, Death Race 2000 had all the elements needed to create a cult classic, such as a great cast, including David Carradine, Martin Kove, Mary Woranov and a scene stealing before-he-was-famous performance from Sylvester Stallone; a witty script, peppered with quotable dialogue (“I think you’re one very large baked potato”); and, despite the disagreements behind the scenes, loads of the prerequisite stuff, including topless girls fighting, nurses being run over, castration by spiky car bonnet, fabulously dinky matte painting effects and people driving really fast to a soundtrack that often sounds like two different songs playing at once. That the illusion of speed was mostly the result of undercranking the cameras, giving the action the jerky harum-scarum quality of a Keystone Cops movie is part of the fun, and more than made up for by the ludicrous designs of the cars themselves, which are adorned with monster teeth, bull horns and wobbling fibreglass Tommy guns. As becomes apparent when one of the competitors takes a high speed diversion through a painted cardboard tunnel and ends up flying over the edge of a cliff, Death Race 2000 is basically an X-rated Road Runner cartoon, with its social satire more in the spirit of adolescent provocation than Rollerball’s cerebral straining, and its on screen splattings designed to elicit chuckles rather than sombre musings on the links between violence and entertainment.

That all being said, Death Race 2000’s joke shop approach to societal collapse seems far more accurate to consequent political developments than Rollerball’s. It’s hard to suppress a shudder when the president of future fascist USA blames a domestic terrorist attack on France and their “stinking European allies”, and the race’s commentators, with their oleaginous mixture of ingratiating showbiz patter and nakedly ambitious bloodlust, wouldn’t look out of place on any American news network right now. Daft it may be, but it’s a pretty sharp satire of an America that was only going to get dafter and more dangerous as the years went by.

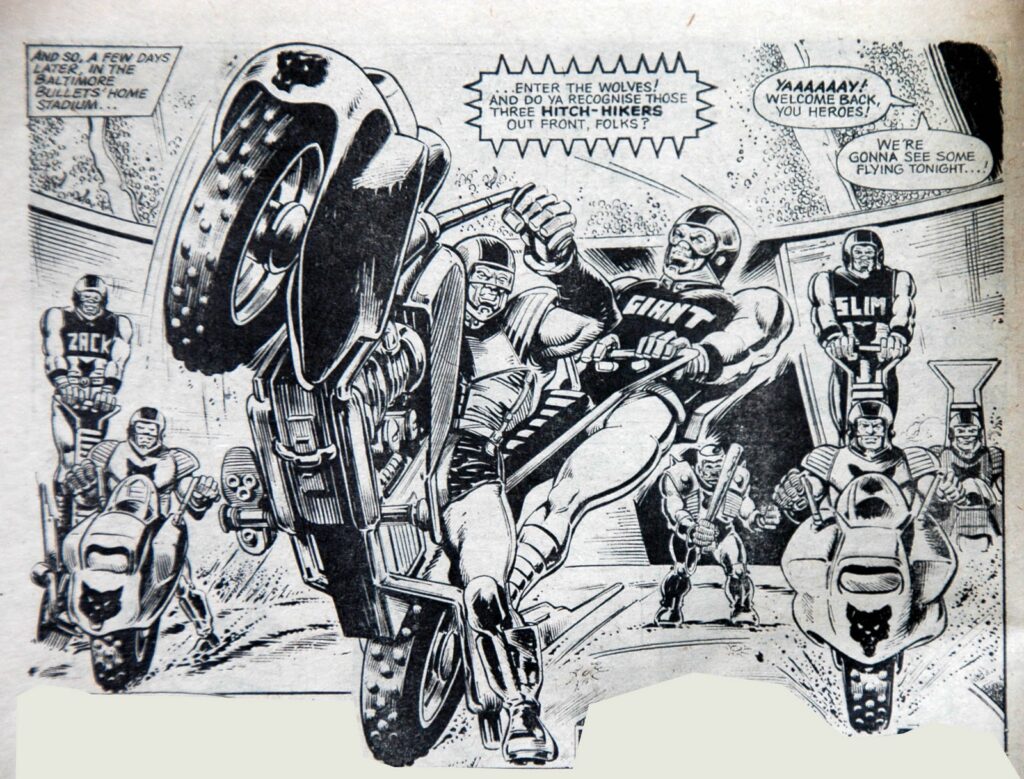

Death Race 2000’s theatrical proto-punk spirit was to form an outsized influence on legendary British sci-fi kid’s comic 2000 AD, the first issue of which was only two years away from publication, with its flagship character Judge Dredd’s costume partly modelled on star David Carradine’s somewhat sexually troubling black leather all-in-one. And 2000 AD was to traffic in anti-authoritarian future sport stories from its first issue, with both Harlem Heroes and sequel Inferno (not to mention Death Game 1999 from 2000 AD’s ill-fated precursor Action!) exhibiting gleefully morbid world building and eccentric larger-than-life characters, with robot coaches and revenge driven homicidal former players the norm. Essentially: Roy Of The Rovers as reimagined by Robert Heinlein.

Interestingly, the primary influence on the actual game being presented in the comic was Rollerball, with Harlem Heroes’ teams engaged in a dangerous jetpack powered version of basketball. This settled into the norm with Rollerball’s titular sport being repurposed into the primary visual influence on everything from the Bitmap Brothers hugely popular video games Speedball and Speedball 2: Brutal Deluxe, to later films such as Ernest Dickerson’s Futuresport (1998, in which the future sport is actually called ‘Futuresport’) and Robert Rodriguez and James Cameron’s Alita: Battle Angel (2019), itself based on a popular long-running manga. Uncharacteristically, the Italians didn’t really step up to the plate where Rollerball rip-offs were concerned, with only Lucio Fulci’s Rome 2033 – The Fighter Centurions (1984) entering the arena, it’s paucity of credible company more than compensated for by its glorious title.

The arena where Death Race 2000 would exhibit its biggest influence would be that of video games however. 1997’s Carmageddon started life as a proposed sequel tie-in to Bartel and Corman’s masterpiece before morphing into its own beast, with its points-for-pedestrians method of progression being enough to get it heavily censored or outright banned in some countries. Later, the Grand Theft Auto series, while not exactly rewarding players for anti-social behaviour, didn’t exactly punish them for it either. It’s seemingly benign encouragement of spree killing rampages leading to serious questions being asked in the House of Lords. But the film’s most long lasting aesthetic influence would prove to be on a different subgenre entirely, that of the post-apocalyptic petrol head movies that sprang up in the wake of Mad Max at the end of the decade. Its cartoon-bright visuals and kinky tone would be the primary influence on one of the best of the Italian cash-in movies that rode that particular wave. Enzo G. Castellari’s Warriors Of The Wasteland AKA The New Barbarians (1983) was a riotously entertaining judgement-free and stunt-filled fandango in which an outlaw posse of predatory homosexuals terrorise a post-apocalyptic wilderness on souped up golf carts. Its horny, violent energy make it feel like a spiritual sequel to Death Race 2000.

The irony of satirical science fiction concerned with imagined dystopian ‘bread and circus’ cultures becoming infamously popular IRL due to ‘promoting’ the anti-social impulses they’re supposed to be satirising is an unavoidable aspect of the Violent Future Sports story. Rollerball director Norman Jewison was horrified upon being contacted by a group of earnest jocks asking permission to set up a Rollerball league of their own. Had everyone missed the point? Well, probably, yes. And plenty of the films, comics and video games that followed in the wake of Death Race 2000 and Rollerball were exercises in brutal style for its own sake. But for viewers worn out by the constant barrage of clobberings that constituted a large part of the genre there was always Blood Of Heroes AKA Salute Of The Jugger (1989), an underseen post-apocalyptic sports flick that manages to square the pessimistic, character driven melancholy of Rollerball with Death Race 2000’s vividly pulpy world building. Helped along by a typically soulful performance by Rutger Hauer, the wasteland wandering competitors in Blood Of Heroes have no clear idea of why they’re doing what they’re doing anymore. The origins of ‘Jugging’ – a mix of American football and gladiatorial combat played with a dog’s skull in place of a ball – having been lost to history, and the tears and strains of a lifetime of violent competition visible to a tactile degree. It feels a long way from any hope in any kind of tomorrow. Which makes Blood Of Heroes a film which brings the Violent Future Sport genre neatly back to its anxious and apocalyptic origins in 1975, and alarmingly close to our anxious and apocalyptic present. Better get practicing.

Writer’s note: In order to keep this already unwieldy look at the Violent Future Sports phenomena on some semblance of track, I had to be very strict about what I considered for inclusion. To this end I have focussed exclusively on ‘sports films’. Meaning, films in which the protagonists are ‘competitors’ and not ‘contestants’. So, no murderous gameshows a la The Running Man, The Hunger Games, Battle Royale or Squid Game. There was also no way I was going to be able to cover the legacy of 1932’s The Most Dangerous Game, in which prisoners are hunted for sport in films such as Hard Target, Ready Or Not, Surviving The Game, Turkey Shoot, Punishment Park, The Hunt, Hounded, Hard Target 2, Avenging Force, Apex, The Pest, Deadly Prey, Get Duked, The Furies, Bloodlust!, Fuerza Mortal, Death Ring, Hunt Club, Bacurau, The Naked Prey, Run For The Sun and Confessions Of A Psycho Cat without making the piece far too long. Sorry.