After Run- DMC hipped rock fans to rap, and Public Enemy’s militancy had built on the impact of ‘The Message’ to bring those weaned on punk’s political energy into the hip hop fold, it was De La Soul and 3 Feet High And Rising that effectively introduced the rest of the world to this music. Accessible, populist, and devoid of the element of threat that accompanied PE and their more strident contemporaries, the trio’s debut was tailor-made to entice new fans to the most exciting new musical form of the day. But the album’s immediate impact is just one chapter of a story that turns out to be rather more complicated than history’s hindsight initially suggests.

That’s not to say 3 Feet wasn’t a record that opened up hip hop, but it certainly wasn’t the only record to do that: and it did so despite – or quite probably because – being an unintentional byproduct of a free-form creative process in which four people set out to make music which, first and foremost, appealed to their own personal tastes and delighted in sharing some very personal reference points. Moreover, while it’s possible – and not at all unreasonable – to consider De La’s debut as one of a handful of records that pushed a sonic collage methodology of music-making as far as the law would allow, and thus to see 3 Feet High alongside the second LPs by the Jungle Brothers and the Beastie Boys as a last hurrah for unrestrained sample-based creativity, a careful reading of history tells us that’s simply not true.

Those three albums – as brilliant as they all undoubtedly are – did not come out of a creative or cultural vacuum: each one drew on its own set of musical influences and relied on the personalities and idiosyncratic interests of its makers. They were products of their time, and there’s enough of them to ensure none of them can be considered outliers. And, while it is definitely the case that, after the close of the 1980s, mainstream hip hop took a decisive turn away from this mode of working, it’s certainly not true to argue that it became impossible to make records like this purely for legal or financial reasons.

Posterity – and more than a few powerful vested interests with billions at stake in the 21st century’s digital economy – want us to believe that copyright law fatally wounded hip hop creativity, that we’d immediately step back into a world of anything-goes musical experimentation if only those original artists wouldn’t insist on being paid when their work gets re-used. Yet, once you ask the people involved, you find that De La Soul never for a second believed that they should be allowed to use other people’s records without paying for the right to do so; and that they went into the making of this record under no doubt that this was what they would have to do. So 3 Feet High And Rising was made in the same legal world we inhabit today. It’s clear that few records that sound like it have been made since: but not for that reason.

Some years ago I assembled an oral history of 3 Feet High from a series of interviews with several of those involved in making the record, and others who bore witness to its effects and impacts as it began to change the world. Since it was first published, on the sadly defunct Hiphop.com, I’ve occasionally had opportunities to speak further to various folks with interesting light to shed on the record, the times it was born into, and the long shadow it went on to cast. Consider what follows, therefore, to be the story as it stands today – but expect it to be revised further as time moves on, memories reveal new details, and history’s judgement is amended accordingly.

CAN U KEEP A SECRET?

Stetsasonic – ‘Talkin’ All That Jazz’ video

De La Soul’s early moves were fortuitous. Alongside a friend they knew through school – the Stetsasonic member and DJ, Prince Paul – the trio (Posdnous, Maseo and Trugoy the Dove, who later changed his performing moniker to Dave) almost fell in to a way of making music that was an extension of their friendship and lifestyle. That they were immediately embraced and celebrated by their peers was not despite their different sound and style, but because that out-of-nowhere individuality fitted perfectly into hip hop’s Golden Era, when the key ingredient that every artist had to have was a singular vision and an unassailable belief in the unlimited possibilities the music could afford them.

Chuck D (Public Enemy): "Among the great innovators of the classic era, somebody who just decides to say, ‘You know man, fuck it. If they’re there, then we’re gonna totally be on this other side’, was De La Soul and Prince Paul. And Prince Paul also comes from the understanding of the most under-rated group of the classic era, and possibly of all time – Stetsasonic. The first hip hop band: the band that made The Roots understand the way they could go in the 90s. In Stet you had minds like Deelite and Daddy-O, and also Prince Paul, whose ideas manifested into De La Soul, these young innovators from Long Island. And when you see a record like that, you go ‘What the fuck? These guys is crazier than we are!’ That was the beauty of that era: everybody had to carve out their own private Idaho."

Posdnous: "We were the same kids who had every Kool G Rap album, every Rakim song, all the early Juice Crew stuff. We loved Run DMC, knew every lyric to [Boogie Down Productions’ debut] Criminal Minded. We were just fans of the music. Whatever was out at that time, that’s what we were on, hardcore or not. But regardless of what we were into, we always were all about what we were gonna do when we ever got the chance to get out there. It wasn’t like we thought to ourselves, ‘We’re gonna try our best and make sure we come out as different as possible from what’s out,’ it’s just that it was the natural way how we were. We had the funk and soul from Mase’s side, the calypso and soul from Dave’s side, and my father’s jazz and blues and soul and gospel side, and we just put that all together with our own influences."

Prince Paul: "I kind of knew of them in school, but not as De La Soul, just from seeing them around. We all went to the same high school, but I never knew they emceed. It turned out that Mase, De La Soul’s DJ, he was a DJ for this guy named Gangster B, and it just so happens that our high school music teacher, this guy named Everett Collins, decided to start his own label. He signed Gangster B, and Maseo was his DJ. And he wanted me to program a beat for Gangster B."

Pos: "Mr Collins lived on my block. He was working with a couple of artists. He used to play drums for a group named Surface, and he also toured with the Isley Brothers. Mase was gonna help this gentleman by the name of Gangster B who was coming out on Mr Collins’ label, and that’s how Mase started to work with Paul. We all knew Paul, you just knew who he was. ‘That’s DJ Paul!’ You know? We’d go to parties and he’d be there. Even before Paul was in Stet he was a very popular and respected DJ in the neighbourhood, so I mean we all knew him in passing. But it was Mase’s relationship that got forged with him first, and from there Mase introduced him on a more personal level to myself and Dave."

Paul: "So I brought the drum machine I had at the time, called Sequential Tom. And the cool thing about that drum machine was you were able to reverse the beats and play ’em backwards. And so I programmed one part of it, and then played the next part backwards. And they were like, ‘Yo! Do the whole beat backwards, like [the Beastie Boys track] ‘Paul Revere’!’ I’m like, ‘No, that’s biting, and biting is a crime!’ But they went ‘Do it! Do it!’ I did it, and it sounded horrible. Mase had seen me all miserable and he was taking sides with me! So Mase came to me and said, ‘Look, I got a group, they’re called De La Soul – there’s two emcees and I’m the DJ. And that’s my real group. Whatever you wanna do, we’ll do it’. I guess because they respected me because I was the one guy in the neighbourhood who made records.

A NEW STYLE OF SPEAK

‘Plug Tunin’

De La Soul arrived fully formed in the minds of a global audience as debut single ‘Plug Tunin’ made a late play for the end-of-year highlights lists in 1988 and follow-up ‘Jenifa (Taught Me)’ acted as the perfect lead-in for the March 89 release of their debut album. Behind the scenes, making the record and getting signed was almost as easy and as relaxed as the music sounded.

Paul: "Later on, Mase came by my house and brought their demo. It was a rough of ‘Plug Tunin’. This was probably the end of 86, ‘cos we started the new year working on the demos. And I was, ‘Oh my God!’ It was very stripped down. It still had the main loop, though it wasn’t really arranged that well. But just to hear the potential! I was like, ‘Oh my God! Let me hold this tape, come back tomorrow, bring the emcees, watch what I do with it.’ That was the ego in me! I added a whole bunch of little things to it. This was back in the days when we dubbed cassettes, because I had a four- track. So I dubbed all the other stuff over it, added the extra beats, the break, the little piano, the Billy Joel piece [a sample from the Joel track ‘Stiletto’]. Then they came over, and then I played it for them, and they were like, ‘Wow! That’s great!’ And I was like, ‘Yo! Let’s work together! Let’s go into the studio, go get your money together, let’s go straight 24-track and let’s forget making little cheesy 4-track demos.’ And that’s what they did."

Pos: "I remember when we first got together with Paul and he told me all of the things he was gonna put to ‘Plug Tunin’. Cos I did ‘Plug Tunin’: it was my father’s record [‘Written On The Wall’ by The Invitations, which gave ‘Plug Tunin’ its main loop], I put it together, put it into song form. And then Mase gave Paul a tape of it, and Paul then brought us over to his house and told us ‘I’m gonna put this to it,’ and we would hear it, and go ‘Damn! That sounds incredible!’ Then he’s, ‘I’m gonna add this little James Brown horn stab to it…’ I was very concerned about what he was gonna do to the music that I was trying my best to produce, which was my first stuff, but right from there he made me feel at ease. He was a person who was thinking on the same level as us."

Afrika Baby Bam (Jungle Brothers): "De La got to Prince Paul, and Prince Paul already had some masterminded things that he couldn’t get off on Stetsasonic. He had the quirkiness, the P-Funk that he wanted to do with Stetsasonic, but he was being overpowered by Daddy-O who was doing most of the production."

Paul: "They all had day jobs, everybody put their money together, and we went to Calliope [studio, in New York] because that was the studio I’d worked in with Stetsasonic. I remember specifically it made a lot of the group feel uneasy, me bringing them in. ‘Who are these guys? Why you got them hanging around?’ I’m a nerd, they’re nerds, you know? I remember I asked Daddy-O – ‘Yo, you wanna help me produce some of this stuff?’ Because everybody knew Daddy-O, he was kind of a famous guy, and I thought it’d be kinda cool. He’s an elder, plus he’s Daddy-O! But he was like, ‘No, they sound too much like Ultramagnetic.’ I was like, ‘Alright then, cool, I’ll do it myself.’ And thank God I did! The first demo is exactly what the first single was: ‘Plug Tunin”, [b-side] ‘Freedom Of Speak’, we had a little bug-out piece on the end, though now they call ’em skits, and that was it. So now we had a demo."

Afrika: "The first time I heard of De La Soul was funny. I was sitting in Red [Alert]’s room, and he had demo tapes and acetates. I would listen to records as they came in, and he’d ask me what I thought of them. And, like, he had this cassette, and I remember it clearly. It had this blue sticker over the whole cassette, and it said ‘De La Soul.’ We had just gotten back from England, this was in September, so I think it was probably a few months pre-Tommy Boy. I don’t think Red had got the tape from anybody in De La, he probably had got it from Prince Paul. Anyway, I’m saying to myself, ‘De La Soul? What is this? Is this a Latin rap group?’ And I’m gonna tell you: instinctively – and it might have been to my own ignorance, because there was a rapper I think in one of these old school groups who was Hispanic – but I was like, ‘It’s too soon for that. Why would somebody try to go there?’ And I put the tape in and it was ‘Plug Tunin’. And I’m like, ‘Oh, they’re not Puerto Rican! This is cool.’ That’s how prejudiced the average rapper might have been! The new rappers, not the old school rappers. And the purists might have been by that point. We wasn’t accepting west coast, we wasn’t accepting European rappers, we wasn’t accepting commercial rap, we wasn’t accepting Latino rap. So I put it in, and I was like, ‘Oh, ‘Plug Tunin’! I know that beat, that’s a cool beat. It’s different’."

Paul: "I didn’t want to go to Tommy Boy. I was already there – we were having problems being there with Stetsasonic. I gave it to Daddy O to shop, because he was shopping this guy named Frankie J, and I didn’t know anybody. Turns out people were more interested in us than they were in his artist! We kind of took over. And somewhere in the process I got it to Profile, so we met up with Profile. This was right before they put out ‘It Takes Two’. They were like, ‘Hey, we just signed this guy Rob Base, check it out, it’s got a cool hook.’ And next thing you know it was a huge record. So they wanted to sign us. Geffen was just starting to pop off and they wanted to sign a rap act, and we would have been the first ones on Geffen. And Geffen was offering a lot of money. Oh my gosh! Back then it was almost… if I’m correct it was more than $20,000, just for a single. That’s a lot of money for a single. Profile was about $10,000, which I thought was really good.

"But the reason I went to Tommy Boy, and this is a story I always have to correct because people are like, ‘Oh, Daddy O brought it to Tommy Boy, he gets credit.’ Or even, a lot of times, ‘Dante Ross brought it to Tommy Boy’: Dante Ross wasn’t even working at Tommy Boy then. The only reason why they went to Tommy Boy, the only reason the tape ever got there, was because, while I was in the studio mixing it down, a gentleman by the name of Rod Houston worked at Tommy Boy. He was in the studio, and he was like, ‘Yo, you should bring this to Tommy Boy.’ I was like, ‘I wasn’t even thinking about Tommy Boy for this!’ And he said, ‘No, you should let Monica [Lynch, Tommy Boy president] hear this’. So he brought it to Tommy Boy, and he never got credit. Credit always went to Dante, it went to Daddy O, and they probably were getting plaques and stuff! ‘Thanks for finding De La, or getting them signed!’ And those guys had nothing to do with it! It was a publicity stunt. Rod was doing videos, he was in video productions, and now he’s doing voiceovers. He’s the guy on the radio now doing all the Burger King commercials.

"So it came to the point where we had the three offers, and I was like, ‘What do you wanna do?’ And they were like, ‘We wanna go with Tommy Boy. What do you think?’ I was like, ‘I wanna go with Profile.’ Geffen I wasn’t too familiar with. So it was three against one. They wanted to go to Tommy Boy ‘cos they felt Tommy Boy showed more interest, which I can understand. So we wound up with Tommy Boy, but Tommy Boy was less money. I was looking at the money factor back then! I’m on Tommy Boy and I ain’t get paid nothing. You know what I’m saying? I haven’t seen a royalty cheque. I’ve seen statements saying ‘You owe us‘! I knew our records didn’t take that much money to make, so I was like, ‘No, I don’t really wanna go here.’ But, I said, ‘Whatever y’all wanna do.’ And that’s how it all turned out. To make the single we got probably $3,000, if that, between the four of us.

"The song was getting played on the mix stations, Red Alert and Mr Magic and all of that, so they [the label] were like, ‘We need another single.’ Cool! So that was when we went in and did ‘Jenifa’ and [b-side] ‘Potholes In My Lawn’. So we did that, and I think there was so much buzz on the group after that – because we did that little cheap video for ‘Potholes…’ – and there was enough buzz for them to say ‘Let’s make an album’."

THIS IS A RECORDING…

Buddy video

The making of 3 Feet High And Rising starred half of the rappers in New York and the occasional random bloke turning up in the studio for no readily apparent reason. As a natural outgrowth of the fraternal and collaborative vibe of the sessions, the Native Tongues collective formed around De La, their friends and like-minded artists the Jungle Brothers the other anchoring point of the unit. Quietly, almost accidentally – certainly without any deliberate attempt at it – this extended family changed the way rap records were made, and altered the industry around them forever.

Paul: "That was a very quick record. We did that in two, two-and-a-half months, and the reason it even took that long is ‘cos I was still with Stet and I had to go on tour in between us recording, so there was some time taken off until I came back so I could finish the album. And that was a pretty low budget. I think we got about $25,000 in total. Everything came out of that: the recording, and we all got paid out of that."

Pos: "Myself and Dave were in our first year of college, and Mase was still in high school. We were just blown away by everything. We were living out our dreams. A lot of the songs was all stuff that was out of our parents’ collections, we would put it together, and Paul would add the spice to it, the recipes that make it right. He would help arrange it with us. It was such a great time."

Paul: "I think the main vibe this time was, ‘Yo, wow! I’m in control! And people listen to me! And not only do people listen to me, they respect me!’ Which, you know, made me… I wouldn’t say ‘cocky,’ but it was so nice to have people say, ‘Yo Paul, what do you think?’ Or, ‘Whatever Paul says.’ And that was amazing. The environment was fun, because Calliope was like a penthouse studio. Acoustically it was horrible but it had so much space. It was so comfortable."

Guru (Gang Starr): "In [Calliope], the main things that were there were a turntable, with a mixer, for sampling and also for scratching. Premier used to bring his [SP] 12 with him, and the disks. We used to do 8-hour lockouts whenever we could get ’em, ‘cos that was a busy studio at that time."

Paul: "We’d just all be sitting around listening to stuff. They had a turntable set up and a mixer, and we all had stacks of records. ‘OK, play the beat on the main speakers, play it loud… Alright!’ And then we’d have something playing, thinking about whatever was on the record… ‘Yeah! That’ll work, but can we pitch-shift it so it’ll fit in key? Yeah, that’s good. Oh, yeah! That’s hot!’ It was just… whatever popped into mind. And I think it almost made me a madman because I had so much control – I wasn’t used to that. Every little idea, every little fantasy of wanting to do stuff, I was able to do. And they [De La] were great. Those guys are very artistic, and I learned a lot from them during that time. So it was a good trade-off."

Pos: "Every single day we went to the studio we took the train. We would probably make it in to the studio in the afternoon. We would take the Long Island Railroad in to New York, and the studio wasn’t that far away from the Central Station that we would get out of. So we would just walk there with all these records and start creating. [Calliope] was such a great studio: it was set up like a loft. Like if you were in somebody’s beautiful loft, only there was all this musical equipment in there. It had a kitchen, a bathroom – it wasn’t all sterilised and studio-looking. It was like you were in someone’s home. You could actually look outside and see the landscape of New York City. It was beautiful. There were a lot of creative juices flowing when we were there."

Dave: "It was exciting. It feels good to just build off of an idea that coincidentally came up, or even if you planned it, to build on something spontaneously. It’s a good feeling to see it come successful at the end and you’re satisfied with it. There were probably a lot of things that we did that we didn’t keep, maybe some songs that we didn’t record, maybe some ideas that we didn’t put on to tape. But most of the stuff, you know, it was acting silly, and just working on that vibe that everybody’s laughing and feeling, and you’re, ‘I’m gonna go in the mic booth and say it. While I do that, you find something to match it. And while he’s finding something to match it, you think of a chorus.’ And I think, you know, it’s a good feeling to see four individuals at the time – myself, Pos, Mase and Prince Paul – just feeding off of each other’s innocence and just making things happen."

Pos: "We always had a great system. Paul really helped us to understand how it’s great to be very spontaneous, but you should also have a plan to fall back on. So we would sit down and write out what we thought we should add to the song: maybe we should add another voice, or cut in this sample, make sure Mase finds some interesting things to cut into the record. So we would have it all mapped out on paper. But you get in there, and then someone would be, say, just sitting in the studio. So we’d go, ‘You know what? You! You, go in there and say something!’ Lord Jamar from Brand Nubian would be in another session and we’d just take him out of his session and make him just say something in a crowd part. That was how we always did! On 3 Feet High And Rising there’s a lot of people, if you read the credits. Like MC Lyte. They weren’t major parts, just people who was in the crowd. Like Baby Chris, who’s now Chris Lighty of Violator [management]. A lot of different people would just come by to visit and they’d wind up in the booth just doing something silly, like whispering, or yelling, things like that."

Afrika: "That was probably the beginning of record companies saying ‘Get a guest artist!’ We probably wound up on ‘Buddy’ as guest artists as a strategic move on Tommy Boy’s end, but we didn’t know it, because we were like, ‘Word, De La’s cool, and Prince Paul’s cool.’ We get in there and we heard a beat they were using, that we were going to use on the first record, that we used to rhyme to, for practise! From one of the Ultimate Breaks And Beats volumes. And we were like, ‘Alright, this is cool.’ Then we heard the little Lionel Ritchie sample over the top, and we were like, ‘This is cool, this is easy’."

Paul: "A lot of the sessions kind of like blend together. I remember one session – it might have been more [follow-up LP] De La Soul Is Dead though – I remember when this kid came up and just walked into the session. We didn’t think too much about him, he was just standing there. He was there probably a good 10 minutes, just standing there, until we started going, ‘Is he a friend of yours?’ ‘No, I thought he was a friend of yours…’ So I turn to him and I’m like, ‘Excuse me, are you here looking for somebody?’ And he’s like, ‘I just wanted to say, I look like him!’ And he was pointing to Trugoy. We were like, ‘Erm… Ohhhhk- aaaay…!’ One, how did he get up there? Two, why’d he wanna walk up there just to say he thought he looked like this guy?! He just left! Very weird."

Afrika: "You know what the common ground was [between the Native Tongues artists]? I’m gonna break it down like this. A lot of common ground was felt through the Red Alert show. ‘I heard you on the show, Nice & Smooth.’ ‘Yeah, I heard you, Jungle Brothers, I’m feeling you.’ Because hip hop was the move, and wherever you could get it was the move. To get it from Chuck Chillout’s show or Red Alert’s show or Mr Magic’s show – just to hear it on radios, it was like being starved from something for the whole week, then you get it. These guys built the bridge. They built the bridge from the old school to the new. You’ve got to think that prior to them, if you heard hip hop, it’s got to have been at a block party, or at some type of jam at a community centre or at somebody’s house, or on the tapes that were made from those events. That’s how exclusive it was; that’s how underground it was. So when these guys came on the air they brought that with ’em. They was mixing the breakbeats. Chuck Chillout? I heard him mixing [the Incredible Bongo Band’s version of] ‘Apache’ or [the Jimmy Castor Band hit] ‘It’s Just Begun’ on the radio. And then play LL Cool J, ‘Rock The Bells’. So they bridged the gap. So it was, who’s next? You heard Nice & Smooth, you heard Jungle Brothers, you heard Big Daddy Kane, you heard De La – we all felt an affinity towards one another. ‘Yo, I heard your joint last night, that’s tight!’ ‘Cos we’d go to the club, like Latin Quarters or Union Square, and bump into one another. Or some other hole in the wall where Joeski Luv was performing ‘Pee-Wee Herman’. Some guys were still on the old school, Kurtis Blow, ‘I’m too fly to talk to you,’ and there were some guys who were, ‘Yo, I like what you did, I appreciate your music’, and it would be a De La. So it wasn’t necessarily like, ‘Yo, we in the same boat, we the Native Tongue family.’ It was more like, ‘I heard you on the line, and I’m inspired by what you’re doing; you heard me on the line, and you’re inspired by what I’m doing – keep up the good work and I look forward to hearing what you come out with next.’ And then it came to, ‘Why don’t you come to the studio, ‘cos we’re getting ready to work on ‘Buddy’? Who’s this guy Q-Tip that y’all brought to the studio?’ And then it was up to the artist to take it to the next level – ‘why don’t we work together?’"

Pos: "The whole recording of that album was just so amazing. We didn’t know anything. We were learning everything from Paul, and then Paul helped upgrade us to where we needed to be. It was like, we were doing it, yet it was so magical. One of the major highlights of the entire project was that there are a lot of things that are respected to this day that were literally just thought of at that moment. Like, we were in the booth, just trying to think of something to do, and I started moaning. ‘Nnnnnuuuuhhhh, uuuuuhhhhh!’ And then I was like, ‘Yeah, we should make a song and call it ‘De La Orgee’!’ And Paul was like, ‘Yeah! Yeah!’

"That was one thing about Paul – even if he thought what we were doing was stupid or crazy, he didn’t tell us. He’d be like, ‘Yeah, try it.’ He would say, ‘You never know!’ Like, say, the ‘A Little Bit Of Soap’ skit – I planned that. I heard the song and wanted to do something called ‘A Little Bit Of Soap’. But the ‘Take It Off’ thing, it was right in there. I think my little brother was there, and he was saying something like ‘Take it off, take take take take it off.’ It was based on a song that was out in Philly called ‘Kick The Ball’ [by Krown Rulers], it was one of our favourite songs at the time. They would have ‘Kick the ball‘, so we went ‘Take it off‘. We just did a funny take on that song. And Paul said ‘Do it! Do it for real!’ So we went in the booth, writing out a couple of ideas, and that wound up being a skit."

Afrika: "I remember I had [Big Daddy] Kane on the phone. I was playing him [Jungle Brothers track] ‘Cos I Got It Like That’, and he was like, ‘Yeah, I hear you doin’ a little singing on there! I got something like that on my album, it’s called ‘The Day You’ll Be Mine’. Let me play it for you over the phone.’ So we could have been affiliated with the Juice Crew at that point! Had KRS-One not come in and dissed ’em. He came in and dissed ’em, and because he was associated with Red, and associated with us, it separated it. That whole BDP thing separated the whole thing. Plus, Kane was one of the final members in the Juice Crew, brought in by Biz. Biz was cool with Red, Biz Mark was in every borough, in every hood, he knew everybody. Those two cats? You couldn’t look at them and say they was solely Juice Crew. They were the nicest cats. Plus they were the best artists in the Juice Crew, so they kind of grew out of that. But, still, that’s the way the people started looking at it. I think the De La thing lent itself to the fact that there was no crew there, they liked our work, we got a chance to work with them, they were rap chemists and their whole thing was cerebral. So they would just be like, ‘Yo, let’s see if it works’."

Dave: "I think we were definitely doing something different, I just didn’t think it would impact with the hip hop audience as it did, or even with people who weren’t in tune to hip hop. I didn’t think our record was going to be so detrimental towards hip hop, which… In hindsight, I don’t think if a record like 3 Feet High And Rising came out, or a group like De La Soul came out, hip hop might not have taken its great turn as it has. Recording the record? No, I mean, who would sit and say ‘This song is about to do something, we’re gonna change the world!’ Nobody really says that, and I’m sure that we didn’t say anything like that! We knew we were doing different music, and if anything there might have been a little bit of a doubt that people would get it or even like it. And I think what was most difficult to understand was how this record seemed so incredible to people. Why is this thing blowing up? Is it that good? And I guess that was to do with because it was so different."

I CAN DO ANYTHING (DELACRATIC)

‘Say No Go’ video

And part of what made it so different was the anything-goes soundbed – the element that is perhaps fixed in the minds of its audience as the defining point of difference between the album and what had gone before it. The irony being, of course, that the vast majority of the music on the album was sampled from old records – so this groundbreaking and completely new sound was, at its molecular level, anything but. The key thing was the recontextualisation and the madcap delight De La and Prince Paul took in finding completely disparate and dissimilar sonic ingredients and making them work beautifully inside single new compositions. Probably the key reason why it worked was that every element was included because it was adored.

‘The Magic Number’

Dave: "A lot of the records were things we were just fans of, stuff we enjoyed, whether it be the Hall & Oates record [‘I Can’t Go For That’, sampled in ‘Say No Go’] or Parliament-Funkadelic. There were so many songs that we used on 3 Feet High And Rising that we just enjoyed for the music, that were favourites of ours. And then, along the way, when those records were being made, you know, the basis of the record was probably something we’d know and love, and then all the extra additives probably that were used as extra were sounds that sounded good to add on to something. Like on ‘The Magic Number’ – all the stuff that’s being scratched and cut at the end, it just sounded good. But for the most part those were records that we enjoyed. We enjoyed [Bob Dorough’s] Multiplication Rock and the song ‘Three Is A Magic Number’, and that’s why we used that. We enjoyed ‘Knee Deep’ by Parliament-Funkadelic [sampled in ‘Me Myself And I’]. It was a mixture, but for the most part the basis of the songs were songs that we appreciated and loved."

Paul: "Pos had the [Bob Dorough] record, he was like ‘Yo, I wanna use that Magic Number record.’ And I remember us being in the studio and going through records, trying to figure out what the beat was. And I remember skipping through the records, and Mase had come across [Double D & Steinski’s] ‘Lesson 3’. We just ran the loop and he just said ‘Let’s try this one.’ And it worked! They were like, ‘Let’s sing Three Is the Magic Number.’ And I said ‘No! When we do it, let’s do it in harmony! I’m gonna use the pitch shifter!’ If you listen to the record real closely you can hear some high voices, some low voices, you know – that was my weak interpretation of being a producer! ‘I’m gonna do the vocals in harmony!’ I had no idea what harmonies were, but I just kinda guessed. Most of it was just real quick and fast. ‘Oh, cool! Sounds good!’ Very little brain- power."

Bob Dorough – ‘3 Is A Magic Number’ video

Pos: "The actual original Multiplication Rock record, that was just a very famous song as a child growing up. It was something you would see on Sunday morning TV. They had a cartoon that would go along with that song, with that entire album called Multiplication Rock, entire cartoons each Saturday. And that was the one we latched on to, to do for 3 Feet High And Rising, because there was three of us. It was a song we were very familiar with. I honestly wasn’t familiar with all the rest of his work – I didn’t realise that he was a very famous musician ’til afterward – but that particular song itself was definitely a part of our lives."

Paul: "I guess, for that particular one, I definitely have to give the credit to Pos, man. That was his concept. I was like, ‘Oh my God! That’s incredible! Let’s get a beat behind it!’ And then I think we put in the Holy Cow record, what’s his name? Lee Dorsey. And sped it up real quick. And at the same time, it’s funny – Biz Mark came in and he was like, ‘Yo! I was gonna use that beat! I was gonna use it a lot slower! Let me hear how y’all used it!’ And that was when he did ‘Just A Friend’. It’s the same beat, but slower." [author’s note: I think Paul is conflating two tracks here: it’s ‘Eye Know’ that samples Lee Dorsey’s version of ‘Get Out My Life Woman’, which Paul may have known from a best-of LP called Holy Cow, and which Biz definitely used on more than one occasion]

Dave: "I think we more or less had the ideas, and the records. The records in our homes and the ideas in our heads. I don’t think we really went out shopping to buy records [to sample] until, I don’t think, the third album. 3 Feet High And Rising was a record that strictly came from ideas, some of them jotted down, some of them filling out spontaneously, and records that were from our own collections."

‘Eye Know’ video

Paul: "’I know I love you better…’ Me and Pos were talking about that, and he was like, ‘I always wanted to use that.’ I was like, ‘Go for it, man – I always liked that record too!’ You know what was so cool about us working together? Just the taste in music: that’s kinda where we come from. In the ’70s, black radio was everything – it was Steely Dan, it was Hall & Oates, it was James Brown, it was Brass Construction, it was Captain & Tennile – it was really well rounded. Whereas I guess today it’s strictly the hot records, or the records that the labels are paying to get played a billion times. So it made you well rounded. And watching MTV early, when there was really no black videos – I guess all you had to watch was the pop stuff, whatever the case was at the time. So I guess we came in from all angles, and appreciating different music to most people. And I guess what was cool for me was I came from a breakbeat angle as well, ‘cos I’d been DJing for so long, and from a point where even before rap records came on wax, so it was like, I was into beat collecting – beats beats beats beats beats! And Pos comes in, and his father has all these crazy records, and he comes from the radio and MTV and stuff, and it’s just clashing the two. And Mase being a DJ, plus his family listen to a whole lot of old R&B, then Trugoy being Haitian and listening to country & western?! It was just combining all of those together. I don’t know how everything materialised, but it was just the best combination that could ever happen at that given time."

HOW MANY TIMES DID THE BATMOBILE CATCH A FLAT?

About that game show…

Pos: "That came all the way at the end. Literally, we were already mixing songs, mixing the album, and Paul was like, ‘You know what? We should still see if we can find something to just glue it together.’ So we started tossing ideas around about what we could do, and once again, stupid old me said something like, ‘Heheh, yeah, we need something like a game show!’ And then Paul was, ‘Yeah! That!’ It was that simple. It wasn’t even like we went from that point and mapped it out – it was all done, right then and there."

Paul: "We did the album. It was done. We were in the studio to sequence it, and I’m writing out the sequence. And I’m thinking, ‘Man, the album needs something!’ I remember pacing in the studio… ‘You know what we’re gonna do? We’re gonna do a game show! And the reason why we’re gonna do a game show is because it’s gonna give an opportunity for people who listen to the album to know who you are individually.’ And that was the problem I had listening to it. A lot of the albums that came out during that time, if you didn’t know the emcees maybe sometimes they sounded alike and you couldn’t distinguish between them. And I was like, ‘We’re gonna make this different; I want everybody to have a persona.’ And in a game show, you always introduce yourself. ‘Hi, my name’s this, I like this, that, I’m from here.’ So that was what I wanted to do. The engineer played the game show host, and we just did it as we went along."

Pos: "Our mix engineer, he was there, and he had a real dry type of voice. So we said, ‘Yo Al, you be the show host!’ And he was, ‘Err, OK!’ And he walked in, he’s supposed to be the one mixing the session and tracking, and he walks in and we’re tracking him instead! That’s how it was. Then we went in and did our little parts as far as the contestants and all, right then and there. Right then and there. It wasn’t like we had the idea then said, ‘Let’s come back tomorrow and do it.’ It was right there. We kicked around what we were gonna say, and someone says something stupid about the Batmobile catching the flat, and Paul laughed. Then someone said something about cereals, so we had to do that. The more dumb it sounded, the more we wanted to keep it."

Paul: "We did it together. Everybody was responsible for their parts, but I more or less arranged it. ‘You first, you second, you do this, you do that’. But as far as everybody’s individual portions, it was like, ‘Off the top of your head!’ We sat down and wrote [the questions] collectively. My whole thing was getting the listener involved in your record: I wanted the listener to become a part. I grew up with children’s records, and I wanted the listener to feel like they’re in it. So that was the whole concept."

Pos: "It was a real competition, but no- one really got it right! ‘Toosh Et Leleh Poo’ was ‘Shut The Hell Up’ backwards. I don’t remember how many times the Batmobile caught a flat: I know it happened once, but I don’t know if it was more than that. I didn’t come up with that one! The fibres in the Shredded Wheat biscuit? I have no fucking idea! I think that was just Paul being an idiot."

Paul: "We got tons of letters, man. But I have no idea if there was a winner."

Pos: "Nobody won. Nobody, man! Hurr hurr hurr."

SAY NO GO

‘Transmitting Live From Mars’

That very few people ever made records as packed with samples as 3 Feet High after it came out is unarguable. And the court case which followed the record’s release – when the group were sued by The Turtles over the use of their version of ‘You Showed Me’ as the sole musical element of the 66-second interlude ‘Transmitting Live From Mars’ – has long been held up as the reason why. Yet the truth is rather more nuanced.

Biz Markie – ‘Alone Again’

In 2010, Thomas Joo, the Martin Luther King Jr. Professor of Law at the University of California Davis, paid around $300 to get the relevant branch of the US court service to digitise the entire written record of the proceedings in another infamous sample-clearance case of that era – the one springing from Biz Markie’s use of Gilbert O’Sullivan’s ‘Alone Again Naturally’ in 1991 – and subjected it to a careful examination. What he found was that the case revealed pretty much the opposite of what the conventional wisdom had said for most of the intervening two decades.

Firstly, testimony given in the case proves that samples were routinely cleared back in the Golden Era, and labels were certainly not unaware that they needed to do so. Second, artists and producers would make the records first, then submit the lists of samples used to the labels for clearance – so the makers of these sample-strewn classics were aware they were going to have to pay to use the raw material they were building their albums out of, and weren’t put off making their records by this fact. And third, the artists doing the sampling, by and large, thought this was a good thing.

While we’re at it, there’s another myth that needs to be struck out. De La Soul’s Tommy Boy albums are not currently available on streaming or download services, but this is not because they contain samples: it’s because the group’s original contract with Tommy Boy – and, presumably, Tommy Boy’s contracts with the artists whose samples it cleared on behalf of the band – were worded in such a way that the label only held the rights to release the music on LP, cassette and CD. Digital distribution systems therefore require new contracts to be signed, potentially inviting new claims by all the artists involved – and the current holder of the Tommy Boy catalogue (Warner Bros) has not, thus far, felt that they’d be able to bring in enough revenue from making these records available online to compensate them for the time and money they’d have to spend on doing that work. There’s a widely held supposition that it’s been impossible to reissue 3 Feet High And Rising because all the samples would have to be re-cleared, at vast expense, but there’s little evidence to support this notion: indeed, Warners reissued the LP in 2001, as a double CD with a disc of remixes, and on vinyl; and again in 2013 on pink and yellow double vinyl.

This does, of course, mean that we need to find a new explanation for why nobody makes records like these any more. In the absence of any better suggestions, here’s one to consider: hip hop changed, as it always did and always will, and the people who made it moved on. Maybe, rather than being hemmed in by worries over potential sample-clearance problems or costs, artists just decided – for their own creative reasons – to make different kinds of records.

Dave: "One of the things that I think will always tie in with the name De La Soul is sampling and sample clearance issues and court dates and so on and so forth. I guess we obviously had a part in making this great business called sample clearance, where there’s people making money just off clearing samples, not even being the people who own the publishing. Clearance companies are definitely booming nowadays. But it was one of those things I think needed to happen, and fortunately we were a part of making it happen. Rightfully, we were definitely wanting to be able to acknowledge the fact that we sampled some people, and they rightfully should know that we used it, and we’d get the clearance for it. And if there has to be a payment structure, let’s make it happen. That’s exactly what we did for 3 Feet High And Rising. We went through the process of making sure we had all the information. Unfortunately, the record was going so much in demand at the time that Tommy Boy didn’t take the opportunity to clear all the samples prior to the record’s release: they just released it anyway, and then we found ourselves in a lot of trouble. But it’s important to us that we clear samples, from day one to today. We definitely want people to be acknowledged for what they’ve done, and paid for what they’ve done."

Professor Tom Joo: "What happens is, if I sample the song and then I go seek permission, I individually negotiate the terms of what’s gonna happen. It’s all a matter of negotiation. There’s no law over who gets the songwriting credit, it’s just a question of what the sampled artist can demand or extract. Think about it this way: the artist is using someone else’s work – how is it different from other situations? This is a classic hold-up problem. If you need a bunch of resources to do a project, then any one of the contributors of the resources can hold up the project and extort a higher price. So, if I’m building a house, I need a plumber and a roofer and a carpenter. The plumber and the roofer are reasonable guys and charge me reasonable rates, and then the carpenter decides he’s gonna hold out, and jack up his price – that’s his right."

The Turtles – ‘You Showed Me’

Paul: "Yeah, I remember there was a law suit going on [with The Turtles]. I remember the lawyer sending me questions: ‘When y’all did this, what did y’all do?’ And blah bah blah. But they more or less sued the label. You know what happened, and why I never really paid much attention? I never made money making a record, so them suing Tommy Boy wasn’t like it was hitting my pockets, because I’d never seen any money. I was like, ‘So? Whatever.’ It wasn’t like I was gonna come home and find my furniture was gone – I didn’t have anything to begin with! You know? I never seen a royalty cheque. But then, even after the law suit I got a nice royalty cheque, which I thought was nice for me, because I made no money. But now I think about it, man, if there hadn’t have been a law suit maybe I’d have made more money!

"But that was their fault – Tommy Boy’s fault. They decided not to clear the sample. We gave them every lick, every sample that we used, and it was their decision. I remember clearly them saying, ‘Oh, this is obscure, don’t worry about this.’ Hall & Oates they had to clear. ‘This? We don’t have to worry about this.’ We wrote down everything, so the label could never say ‘You guys! How could you do this!’ It was never that. They knew it was their fault."

3rd Bass – ‘Pop Goes The Weasel’ video

Professor Joo: "Even people who purport to be defenders of hip hop say: ‘But hip hop is based on appropriating things without paying and without permission.’ But that’s actually not what it is – in fact they did pay, and in fact there is a culture… Culture is a complicated thing, but there seems to be a very strong strand in hip hop culture that you’re supposed to pay respect to the people that you took from. I mean, biting is a mortal sin – or it used to be. But we’re talking about [the golden] era: you know, [3rd Bass’s] ‘Pop Goes the Weasel’ is about what a bad thing it is to use an uncleared sample, right? And in your interview with De La Soul, they say, ‘Of course you’re supposed to pay The Turtles, and I wouldn’t want to use their material without permission,’ and all this kind of stuff. How many rock songs are there where it’s just five minutes of shout-outs? You’re supposed to give credit where credit is due. I think that there really is a strain of thinking that, frankly, I think is racist – that African- American culture consists of a lack of ownership and a lack of authorship, and everybody just does things together. And it’s just kind of like a noble savage kind of deal, right? No – people have egos, and they respect other people’s egos. I take pride in my work and I understand other people’s pride in their work, so I’m not gonna take credit for their work, I’m gonna make sure I acknowledge them."

Prince Paul: "Our court case, yeah, it was known because it was the first. But if you wanna blame somebody [for ending the sampleadelic era], put the blame on Biz! I tell him that all the time. He was the one who blew it totally out of the box. It’s different when somebody says, ‘Hey, don’t use my record’, and you use it. You know what I’m saying? That’s wrong. And very bold! You know? Nobody knew – there were no guidelines for sampling – then he just blew it out of proportion."

Professor Joo: "Biz’s lawyers seemed to be aware that permission was not gonna be forthcoming, but there’s no evidence that Biz personally knew that. His lawyers were in contact with O’Sullivan, and O’Sullivan was a little unclear but didn’t seem to be willing to play ball with them. But Biz Markie himself appears to have been totally out of the loop there. According to his deposition, he recorded the track knowing he had no permission, and then he told his lawyer to get the permission. But he doesn’t have the ability to release a record. Even if he wanted to release a record he couldn’t: the record company has to pull the trigger. And there’s no allegation that he lied about having the permission, so in the end it’s the record company that decided to release it without the permission."

D.A.I.S.Y. AGE

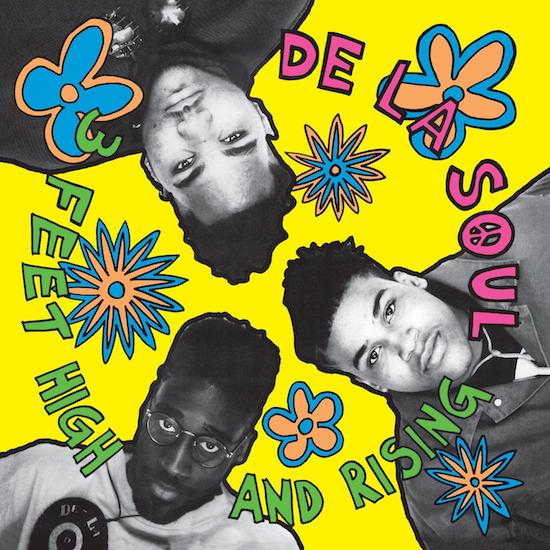

When they announced their comeback by killing off the brand, De La Soul were responding, as much as anything, to the image that had been built around their debut. It’s easy to imagine the group, entirely unaware of how important their record would be considered to be, and how far it and its sleeve art would travel, being entirely happy with the bright primary colours and the evocation of ’60s hippydom that adorned the front of the record – and just as easy to understand why they wouldn’t want to be trapped in that box of preconceptions for the remainder of what continues to be an uncommonly long-lived and reliably innovative hip-hop career. Meanwhile, the impact the record had on their fellow artists was no less significant than the one it had on audiences.

Paul: "[The cover] was all Tommy Boy. I think Monica Lynch came up with the concept, and I think later on that made the group kind of upset, because that made ’em look all hippy-like, the day glo colours. But when you think about it in hindsight, it was a good marketing tool. It worked. I liked it, but I didn’t have any idea… none of us had any idea it would have the impact that it had. I remember, even the people around us, friends who were coming up to the studio, they were like, ‘That record? These guys? How did that happen?!’ I was saying this more as a coach, and I hate to sound like I was insincere, but maybe I was: but I took on this role that I felt as though, I’m almost like their father in the studio. Even though I’m just a year or two older, it’s just like, ‘I’m the older, more experienced guy.’ And I remember at the end just saying, ‘Man, we got a good record. We’re gonna go gold.’ [Laughs] I was saying, ‘Feel good about yourselves! We’re gonna go gold!’ Just to cheer them on and make them feel good. Never in my wildest dreams did I ever think I had a Number One album, Number One singles. This record, it changed… whatever! People were dressing like them! And I had no clue. That was amazing."

Afrika: "It was, ‘Daisy Age? They on something new.’ That had more of the press going, more of middle America, white America, going. I think they had something that the crossover road was more interested in, because it represented that whole 60s hippie culture where there were more white artists. Like your Paul Simons and Art Garfunkels. They were using samples from that era, and also from P- Funk, who were a band where anything goes too. Jungle Brothers, we were moving from keeping the Zulu Nation going… if you look on [Jungle Brothers debut album] Straight Out The Jungle, we thanked artists like Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five. When they made their records there wasn’t really a special thanks section, but we were paying respects to what was becoming known as the old school. And then we moved further into our blackness, by associating with… ‘OK, what we do doesn’t only go back to the old school here in New York City, it goes back to the old school from the African griot poets. Let’s check some Last Poets and Gil Scott Heron out.’ That’s what appealed to me, and that’s what appealed to Mike [G] too. If I was on some, ‘We’re gonna be just like Ill & Al Skratch and we’re gonna buy a big Mercedes Benz and be chillin’,’ Mike would have looked at me like, ‘We’re not gonna be doin’ this long.’ But we moved more into our blackness and then, I think, that’s when it began to mean more to us than hip hop."

Paul: "[Making 3 Feet High…] was never really to outdo anyone for me. But my inspiration at the time was… I remember I was listening to Nation Of Millions, Beastie Boys’ Licensed To Ill, Eazy E’s album [Eazy Duz It], and more so than anything? And if you listen to the album now, you can probably hear it, is George Clinton – and not necessarily for the funk aspects, but conceptually. He conceptualised all his records: like, they’re underwater, or they’re in space, or in the White House. I always appreciated that, and as a kid I was always able to visualise stuff. And I always wanted to make a record like that, and this gave me the opportunity. That’s why it had the little cartoon on the inside. I wanted to get Pedro Bell to do the illustrations but they said it would have been too much like Parliament-Funkadelic, so we couldn’t do it. All that stuff, man! That was me. I wrote that little story inside, with the cartoon – that’s where that came from. Because I wanted to be George Clinton, man! I idolised that man so much! I would skip school to listen to his albums. ‘Ma, I don’t feel good.’ She’d go out to work, and I’d just constantly play his records over and over and over again. So, it’s like this gave me an opportunity to make my Parliament-Funkadelic record, and that’s what 3 Feet High And Rising was. For me.

Jungle Brothers feat De La Soul et al – ‘Doin’ Our Own Dang’

Afrika: "Straight Out The Jungle came out June 88, 3 Feet High And Rising came out in 89, so that was out when we were making our second album. I think we began recording the second album like November, December 88, got in the studio probably January, February, March. But I know De La’s first album was out. Did it have an impact on what we were doing? For me, absolutely not. We almost didn’t do ‘Doin’ Our Own Dang’. It was the suggestion of somebody at Warlock records. The negotiations for Jungle Brothers to be on Warner Brothers was still taking place, and it was almost like it was still Warlock’s record. I remember going and playing them some stuff, and he was like, ‘You should do something with De La. They got y’all on their record, you should get them on yours.’ He was thinking cold business – cold turkey business. So I was like, ‘Yeah, that’s cool, that should work.’ So we did it.

"And when we got to our album, we just was going off of… We’ve been around the world, we’ve been to Europe and Japan, we’ve seen all the cultures that are into Straight Out The Jungle, we got a world view now, we’ve been in clubs where people wanna dance, and clubs where people wanna think; we’re promoting our positivity, and we want people to look at hip hop as something that comes from Africa, that has its origins in Africa. Let’s make this album like a college piece, an intellectual piece: let’s do 16 songs, and… we had 20- something songs for that album, but we wanted to make a body of work. ‘Let’s use something form funk, something from soul, something from disco, something from doo-wop, something that reaches all the way back’ – poetry. ‘Black Woman’, ‘What U Waitin’ 4′. Let’s do an album that encompasses all of that! We was wearin’ our African medallions and identifying with that. We was going to a place in Harlem called Africa House, burning incense and reading books, drinking sorrel and not eating meat, and talking with the elders about Bob Marley and Ghana and South Africa and apartheid. And taking all of those experiences back into the studio and making the studio environment almost like our village, our hut. Just creating that whole environment. So we wasn’t even thinking about Daisy Age. I had this red, gold and green flag with this kid on it who had dreads: I had that hanging up there in the studio. I had all these beads that I made, some of ’em had bells on, and you can hear them on the recording because I didn’t take ’em off when I went in the booth. There was a set of tom drums in the booth that I played on ‘Good News Coming’. It was just about a village, tribal, hut type of environment in the studio. We wasn’t thinking about Daisy Age, about ‘Me Myself And I’, about strategically trying to build off of what De La did, which built off of what we did in a certain way."

Beastie Boys – ‘Shake Your Rump’ video

Paul: "Q- Tip was the first person I heard talking about [Beastie Boys second album] Paul’s Boutique, then I immediately went and bought it. No: I bought it way before I heard Q-Tip talk about it! Right after I bought it, I remember me, him and Pos talking about how great it was. It wasn’t ’til later, ’til I met the Beasties, they was like, ‘Man, we was mad with you when you made 3 Feet High And Rising! That’s what we were doing! That was our concept! We were putting all these samples together and stuff! And we were like, Awww, now we’ve got to go back to the drawing board!’ I was like, ‘Really?’ They were like, ‘Man, we hated you guys!’ Wow!"

Mike D (Beastie Boys): "I do remember… I was telling the story earlier, but… Actually, I don’t remember running into Paul."

Adrock (Beastie Boys): "I feel like I do. I think that was me."

Mike D: "So there you go. But I was just telling the story earlier that I remember the day that I got 3 Feet High And Rising. I don’t know if it was the day it came out, or whatever, but we got it and we were in the studio, or on the way to the studio or whatever, and I remember listening to it, and I felt pretty crushed. I felt, ‘Oh fuck! We’ve been putting all this work in, and like, they did it!’ You know what I mean?"

MCA (Beastie Boys): "I think they’re pretty different, actually."

Mike: "I think in hindsight, they’re radically different albums in terms of tone and feel and even just in terms of what they do. But it was just…"

MCA: "Most rap records in the immediate time before that was just beats, and people yelling over the beats. All the beats were trying to sound really big."

Mike: "And shit trying to sound hard: instead of being brain-expanding material, they were trying to be hard. And all of a sudden De La Soul came out with, like, musically and lyrically a whole expansion of ideas. And Paul’s Boutique did too."

Adrock: "Public Enemy too."

Mike: "Yeah, the Bomb Squad too. That was at the same time. There was an eclecticism to what they did but it was somehow more focused, or more purposefully kept to a certain tone, whereas 3 Feet High And Rising had such crazy, different shit on it, going on at the same time."

Adrock: "3 Feet High And Rising also sounded like those tapes you made when you were a little kid, on your tape deck, when you tape all stuff. All those skits and things. I’m not saying it’s a child’s thing, though."

Mike: "[laughing] You’re calling Paul a child?"

Adrock: "No."

Mike: "But the shit still sounds really good today."

Paul: "It was funny, because I used Licensed To Ill as a basis for a lot of the stuff! I was heavily listening to Licensed To Ill! That was my favourite! I thought Rick Rubin was a genius. Oh my God, I loved that record! That had a lot to do with 3 Feet High And Rising – just the fun behind it. And even at the end, on ‘Let’s Get Ill’, where they’re cutting in Mister Ed, and there’s all that awkward stuff, I’m like, ‘God! This is incredible!’ And I said, ‘Man, I based a lot of my stuff on y’all!’ Isn’t that weird?

De La Soul take part in the Gods Of Rap tour with Public Enemy and Wu-Tang Clan (London Wembley SSE Arena, May 10; Manchester Arena, 11; Glasgow SSE Hydro, 12). Stetsasonic play their first UK gig for 28 years at the Jazz Cafe on March 20