That my hair at the front still flops down over my eyes gives, I think, some indication of the continuing after effects of encountering David Sylvian at an impressionable age. Or perhaps more accurately at an age when pop music was largely all the impressionable adolescent had with which to shape an identity of their own. At a time, too, when information about it was more often conveyed to me through promotional appearances and videos on kids TV shows and the glossy full-colour pages of teen magazines such as Smash Hits, Record Mirror and Number One, than the radio and the weekly inky music press, image was no less important than the music itself. But then, what a sound Japan had. I’ll be haunted to my grave by ‘Ghosts’, the group’s singular, literally and figuratively, top five hit from 1982. ‘Ghosts’ was less a song than the absence of a song. Or what a song might sound like if the rest of it withered and decayed, leaving only a few spectral traces of what once was hanging around and rattling its chains, or chimes, perhaps more accurately. Sylvian’s voice, mannered but mesmerising,was a cry of anguish in the dark.

By 1984, however, Japan had long since split up amid unseemly stories of stolen girlfriends and tabloid splashes about car crash injuries and the singer’s supposed scarring for life. Pop moved faster back then, with whole careers scarcely lasting longer than the lifespans of mayflies and musical trends passing in the blink of an eye. Japan, unfairly or otherwise, had been lumped in with the New Romantics: Spandau Ballet, Classix Nouveaux and Duran Duran et al, the latter having previously tried unsuccessfully to persuade Sylvian to produce them. But anything that smacked of frilly-shirted New Romanticism was by now hopelessly passé, as poor old Steve Strange was to discover when his Visage comeback single ‘Love Glove’ comprehensively failed to fist its way into the charts. Duran themselves were soon enough to be spotted sporting designer-stubble and rocking out in post-apocalyptic Mad Max-style leather biker gear in the promo for ‘Wild Boys’. The Human League, fronted by a similarly be-stubbled Phil Oakey, the asymmetric-hairstyle superseded by a nape-draping mullet, were (shock, horror) found to be playing electric guitars on ‘The Lebanon’ in 1984. While fellow Sheffielders ABC were to re-emerge later that same year punting the socially-conscious hi-energy of ‘(How to Be A) Millionaire’ and dressed as if they’d stepped out of 1972, in the process inaugurating a retro cartoon-character look that bested Deee-Lite and S’Express by a good half decade. Not that many people, in an epoch of oversized sloganeering t-shirts (‘Choose Life’, “Frankie Say…’etc.,) and stretch denim jeans, seemed quite ready to embrace satin wing-collared shirts and platform shoes again just yet; ABC’s return proved muted and the image was soon shelved.

Tears For Fears, lest they in any way be tarnished by association and indulging in a bit of cod-Freudian-kill your father stuff, were, I dimly recall, even quoted in the summer of 1984, saying something along the lines of that once they’d been on ‘Planet Sylvian’ but now they were on ‘Planet rock and roll’ when discussing ‘Mothers Talk’, their clattering drum-and-string sample heavy new single – a decidedly portentous anti-nuclear war record much in keeping with the overriding sonic and thematic palate of the year. For this, after all, was the summer of Frankie Goes To Hollywood and ‘Two Tribes’, perhaps the most gloriously cacophonous record ever to spend over two months at number one.

There it was, week after week on Top Of The Pops, with its air raid warning opening voiced by the helicopter guy from the Barratt Homes ads. That bassline, tat tatting like an MP 40 submachine gun, and orchestral stabs landing like shells from a howitzer, and shrill guitar wails that barely relent for the opening two and a half minutes. Over all this were Holly Johnson and Paul Rutherford, who sang as if aboard a warship under fire. The song’s lyrics, largely unintelligible, were uttered much like a series of garbled commands from the captain (Johnson) on the bridge and seconded by his loyal chief mate (Rutherford) as they struggled to be heard over the fray. (The analogy only goes so far of course; Rutherford’s Castro-clone moustache more RAF or army than navy, but even so.) The chorus, that was easy, and came out foghorn-loud and clear. Its sentiment that global nuclear war wasn’t really a game worth playing, having already been drummed into us the previous summer by WarGames; that season’s popular teen movie starring a toothsome Matthew Broderick as a young gamer pitting his wits against a malevolent computer intent on on starting World War 3. Think 2001: A Space Odyssey’s HAL 9000 updated for the Pac-Man hacker generation with noughts and crosses thrown in.

But frankly I’ve still no idea who the ‘black gas’ Frankie sang about were. Or how, with then some three million unemployed, anyone got to work for them. Though there was probably a YTS scheme; on leaving school three years later, I was offered one myself, in oboe-making, and on the basis of an interview with a careers officer where I had expressed an interest in music and was in possession of an O Level in craft, design and technology. Such were the Thatcherite ruses to manipulate the unemployment figures back in the day.

But in the summer of 1984, ‘Two Tribes’ was more like the ‘Black Hit Of Space’, the Human League number about an intergalactic chart topper that sucked up everything in its wake. It was utterly unavoidable, bleeding out of end of the line Ford Cortina car radios, jean shop in-store stereos and the mainstay along with Miami Sound Machine’s ‘Doctor Beat’ and Wham!’s ‘Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go’ of every church hall disco I attended. The C of E was, or certainly in my limited local experience, appeared to be, quite CND. Though who in their right mind wasn’t? Lots of voters apparently, who in the previous year’s general election had comprehensively told Michael Foot and the Labour Party to bugger off with their nonsense about unilateral disarmament. Post-Falklands the mood had unfortunately been less ‘protect and survive’ and more ‘bring it on’.

Yet here, just a few months later, perhaps many of those self-same voters were hoovering up the streams of 12-inch and cassette remix editions of the anti-nuke anthem ‘Two Tribes’. Or possibly not, since chart pop music as a work in progress less burdened by its heritage remained the preserve of the young or youngish at heart. Though the Tory party had a fairly active youth wing at the time, which organised discos of their own in another draughty hall elsewhere in my hometown, as an (un)committed socialist I never went to one so I have no idea what they played. Possibly ‘Blue Monday’ by New Order or PiL’s ‘This Is Not A Love Song’, with its line “Big business is very wise, I’m crossing over to free enterprise”. The thudding bassline of the latter is hardly a million miles off ‘Relax’, come to think of it.

‘Two Tribes’ was, of course, to soundtrack, subliminally or otherwise, a very real domestic battle, that of the Miners’ Strike. A labour dispute that ensured ‘Coal Not Dole’ badges, donkey jackets and fingerless gloves, the mufti of the picket line, were to become de rigueur at my school. However, growing up, as I did, in a sleepy retirement resort on the none-more True Blue south coast, the strike was experienced solely via dubious, as we later learned, TV news bulletins. Bulletins where footage of the police charging on pickets at the Orgreave coke works was reversed by the BBC in a move that subsequently seemed suitably Orwellian for this of all years. A year that would run out to the stuttering strains of the Eurythmics’ ‘Sexcrime (Nineteen Eighty-Four)’ – the lead single from their soundtrack album to the movie of the book, a film in which a convincingly tubercular-looking John Hurt (Bernard Sumner-severe short-back ’n’ sides haircut, ration book gaunt and phlegmy throated), was cast as Winston Smith, the party drudge who rebels, that opened that October.

Amid all of this, David Sylvian stood out to say the least. For one thing unlike Frankie and Tears For Fears, or Nik Kershaw, Culture Club, Nena, Depeche Mode, Ultravox, Big Country and Captain Sensible, the latter respectively with ‘I Won’t Let The Sun Go Down on Me’, ‘The War Song’, ‘99 Luftballons’, ‘People Are People’, ‘Dancing With Tears In My Eyes’, ‘Where The Rose Is Sown’ and ‘Glad It’s All Over’, he didn’t have a anti-war single out. This musical trend I surmise at this distance possibly owed as much to the 70th anniversary of the outbreak of the First World War as the then-omnipresent threat of a nuclear apocalypse. A likely harbinger was Paul McCartney, whose chart topping ‘Pipes Of Peace’ was released in December 1983, backed by a high-end video dramatising the so-called Christmas Truce of 1914, when German and British soldiers had briefly put down their arms and played football on no man’s land.

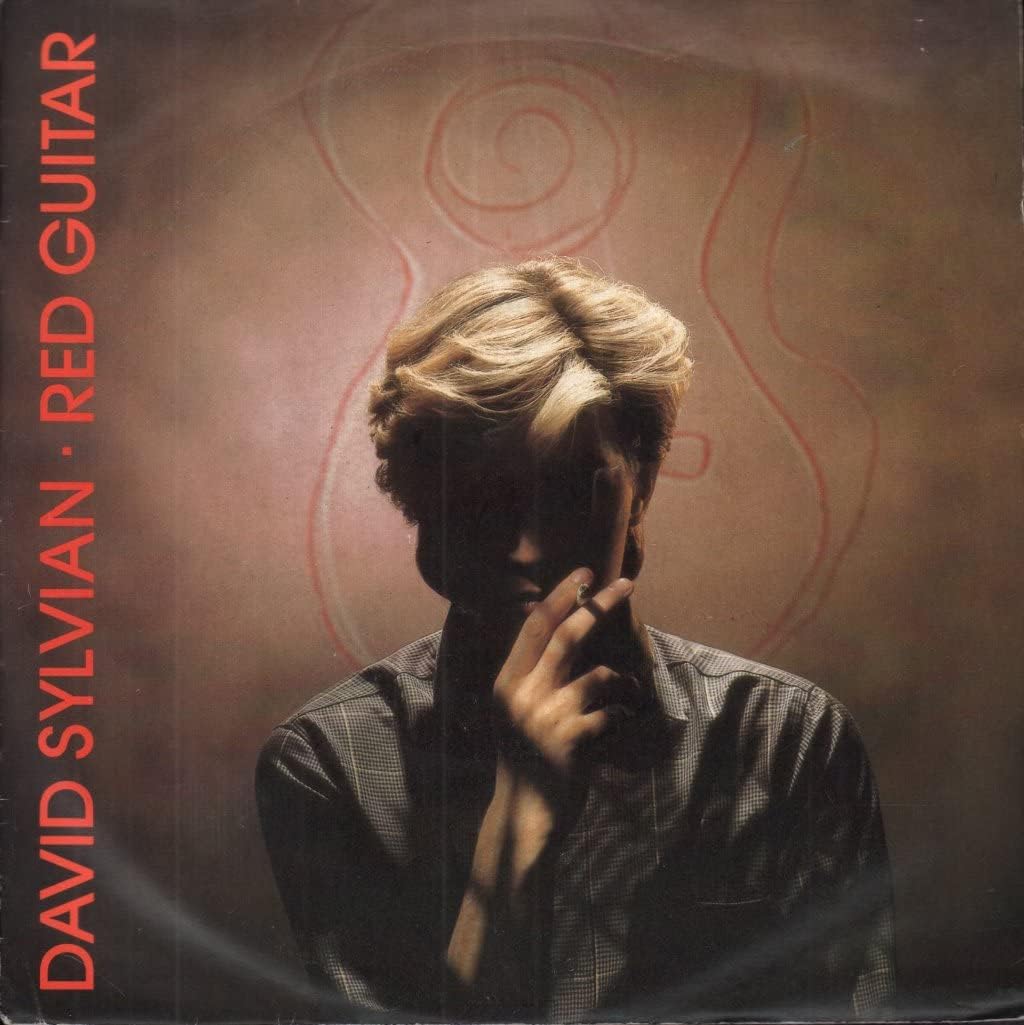

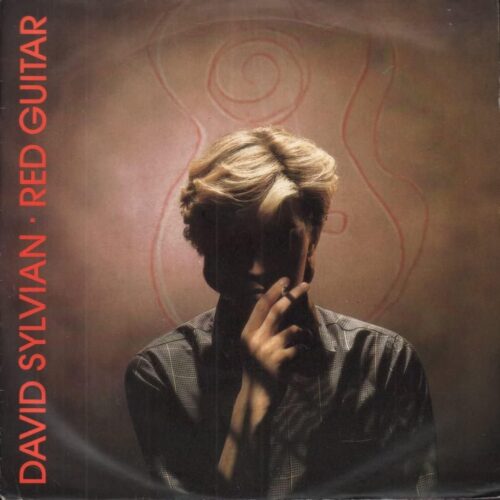

The startling first single from Sylvian’s debut solo album, Brilliant Trees, the jazzy ‘Red Guitar’ with its driving latin-inflected staccato piano trills and rubbery bass line, would be promoted by an equally memorable video. One similarly directed like a movie, albeit something in the dream-like vein of Bunuel, by the Dutch photographer and future feature film-director Anton Corbijn.

Shot in Corbijn’s trademark monochrome, and boasting a calligraphic title sequence that announced ‘David Sylvian in Red Guitar with Angus McBean special guest’ it opened with a close-up of the face of some old codger with a heavy white beard, his look somewhere between a twinkle-eyed Santa and Captain Birdseye. The man’s almost immediate envelopment in a swirling cloud of fog, only added to the maritime vibe of the latter. This was McBean, whose name meant nothing to me then but as I was to discover, was the Welsh-born photographer who had shot the cover of the first Beatles LP sleeve, the band standing on the balcony of EMI’s offices in Manchester Square, beaming, as someone once observed, like (fab) four grateful tenants of a new council flat, and subsequently reprised seven, beardier, weirdier years later for the ‘blue’ compilation album, 1967-1970. Prior to this McBean had provided full fat colour cover portraits for Cliff Richard and The Shadows, including one of Cliff poised to blow out a bunch of candles raked like rocky stalagmites on an oversized birthday cake on the celebratory sleeve of 21 Today. The image, if intended to convey Cliff and the group’s wholesome ‘boys next door’ image, is more than a little camp and its technicolour scheme as gloriously overblown as anything by Douglas Sirk.

As it turned out, McBean was a veteran of the First World War, and a leading member of the pacifistic Kindred of the Kibbo Kift in the 1920s who was later imprisoned for his homosexuality during the Second World War. Sylvian’s interest in him stemmed not from his post-war commercial pop output but for his earlier surrealist work, and in particular his celebrity portraits of such 1930s stars of the screen and stage as Peggy Ashcroft, Dorothy Dickson and Diana Churchill. Corbin’s video was, in effect, an extended homage, with Sylvian pictured as if buried up to the his neck in sand and rocks and a halo of twigs framing his Princess Diana-esque helmet of bleach blonde hair in respectful mimicry of McBean’s 1938 photograph of the actress Flora Robson.

All of this information is easy enough to Google now, and I can’t in all honesty say how many of the pieces of this particular pop art history puzzle I could have put together back in 1984. Yet I was an assiduous collector of references, the artier the better, dropped by pop stars in interviews. I clearly remember that just a few months earlier, Green Gartside of Scritti Politti, then in the midst of launching the opening salvo of his determined assault on the charts with the irresistible ‘Wood Beez (Pray Like Aretha Franklin)’, a precision engineered soaring slab of techno-soul-funk that kerchinged like a cash register, was photographed brandishing a book on Joseph Beuys in a favourite-things type profile in Smash Hits. He did also pick white chocolate (also featured on the record’s sleeve) to highlight a softer side, perhaps, though notably a rather posher variety than the Milky Bars that the magazine’s teenage readership were likely to encounter in their nearest Wavy Line supermarket.

As a curious teenager, in perhaps all senses of the word, I took note of these things. I was trying to find my way in the world and simply eager for knowledge of a life beyond the brutalities of my all-boys state comprehensive and weekends spent mooching around the local shopping precinct and consuming Woodpecker cider in seafront shelters with like-minded misfits. All of us were bonded over a shared annoyance at missing out on punk and enamoured of Echo And The Bunnymen, intrigued by Propaganda and refused entry en masse to see Purple Rain at the local Odeon for being under 15.

I was interested in art but my exposure to it came almost entirely through the ephemera of record sleeves, music videos, films late at night on BBC Two and Channel 4 and TV documentaries. Especially the BBC’s Arena strand – ‘Beat This’, an episode from that year’s series, for instance, offered a primer in hip hop and graffiti art, a none-cooler Kool Herc caught speeding through a war-torn looking Bronx of burnt out storefronts in an open-top car with a pair of megalith-sized speakers on the back seat. My family were not gallery-goers, (frankly whose were in the provinces in 1984?). Football pitches, cricket grounds, the odd museum or stately home and garden centres were their preferred go-to leisure hour destinations. Nor was there all that much by way of music in the house growing up either. The weekly dose of Jimmy Savile’s golden oldies show on Radio 2 with the Sunday roast and the occasional spin of my mother’s copy of ‘Guilty’ by Barbara Streisand and Barry Gibb on the coffin-shaped stereogram were about it. My father had relinquished his prized collection of Buddy Holly 78s soon after leaving home, seeing the giving up of such childish things as part and parcel of becoming an adult.

By contrast my LP copy of Brilliant Trees, along with its three seven-inch singles, ‘Red Guitar’, ‘The Ink In The Well’ (in a fold-out poster sleeve with postcards, these sadly long-since lost after years of decorative service Blu-Tacked to the walls of a run of rental bedrooms) and ‘Pulling Punches’ are with me after 39 years. I’ve grown up with these records and arguably these records also helped me grow up, supplying an aesthetic sense of sorts that I’ve carried with me ever since. The lyrics to the flamenco-flavoured ‘The Ink In The Well’ alone contained a patchwork of allusions, conspicuous and veiled, to Pablo Picasso, Jean Cocteau and Jean Paul Sartre’s The Roads To Freedom novels for autodidactically-inclined listeners like myself to nibble on at their leisure.

A pre-Stephen Yaxley-Lennon-supporting Morrissey of The Smiths provided similarly rich and occasionally overlapping pickings at the time. A still of Jean Marais from Cocteau’s film Orphée, for instance, appeared on the sleeve of ‘This Charming Man’. Both men, born just a year apart, had shared youthful infatuations with the New York Dolls and Andy Warhol and his Factory of Superstars. The first version of the Velvet Underground & Nico’s ‘All Tomorrow’s Parties’ I ever heard was the cover by Japan on their 1979 album Quiet Life – a record re-issued a couple of years earlier to cash-in on the chart success of ‘Ghosts’ on the pocket-money-friendly budget Fame label.

Sylvian, like Morrissey, was also one of pop’s more ostentatious glasses-wearers. Having since the age of about 9, been issued with a pair of bog-standard, square-framed NHS numbers in a sturdy brown plastic issued with a snap-shut cloth-covered tin case, I could see little romance in The Smiths’ frontman’s specs. While the gold-rimmed round ones that Sylvian was pictured wearing in the stark black and white photo (shot by Steve Jansen, his younger brother and Japan’s drummer) that graced the sleeve of ‘Ghosts’ exuded an assured stylish brain-y elegance I desperately yearned to emulate.

Morrissey’s curriculum too always seemed far more grounded – and purposely so – in the provincial Northern 1960s kitchen sink than the international art house, cinematically speaking, of Sylvian. After all, this was a guy who smoked, (as Smash Hits again informed me), the fancy French throat-stripping Disque Bleu cigarettes, had a Japanese photographer girlfriend and made collages out of Polaroids, for Christ’s sake. The avowedly celibate Moz, by contrast, seemed to subsist on a hair-shirted diet of yoghurt, fruit and almonds and toast and tea and spoke fondly of Coronation Street. No contest, then.

There were also Sylvian’s musical collaborators on this album of just seven, ruminative tracks, the shortest of which, ‘Ink In The Well’ was four and half minutes long. The flugelhorn that added a plaintive almost Sketches Of Spain air to this particular number was supplied by top Canadian brassman Kenny Wheeler, whose 1969 LP Windmill Tilter: The Story Of Don Quixote, stands as one of Brit Jazz’s most revered albums. The supple double bass, meanwhile, that underscores the song, came from Danny Thompson of Pentangle and John Martyn’s Solid Air fame. (I’d heard neither then, and have never got on with the latter anyway.) Flipping the seven-inch single over, there was the instrumental version of ‘Weathered Wall’, another Brilliant Trees album track.

Funereally-paced with a woozy wailing refrain dimly reminiscent of the sort of snake charmer’s flute that might feature in a Turkish Delight commercial, and intermittent snatches of obscure radio broadcasts, it felt much like twisting the dial of a transistor and alighting on a station from some far flung territory. One whose coordinates were hazy and lands quite possibly unmapped. ‘Weathered Walls’’ personnel were to prove suitably polyglot with the Yellow Magic Orchestra’s Ryuichi Sakamoto, Holger Czukay of Can and the American trumpeter Jon Hassell all contributing to the piece.

Sakamoto I was familiar with, if largely from the film Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, and the vocal version of its theme song he and Sylvian had produced together, Forbidden Colours (a variant of which handily enough also appeared on the B-side to ‘Red Guitar’). My knowledge of Can at this point extended only to noting they were credited (along with Roxy Music) of ‘seducing’ Steven Severin ‘away from school work’. This, at least, was according to the brief biography the Siouxsie And The Banshees bassist had been allotted in that year’s Smash Hits sticker album. It was enough to pique my interest. That Hassell had also worked on an album with Roxy’s Brian Eno (Fourth World, Vol. 1: Possible Musics), seems almost a coincidence too far. But there it is. Some of these leads naturally lay dormant for a decade or more. And on eventually meeting Jon Hassell in person at an event in Peckham a few years ago, where he bristled slightly when someone else mentioned his album with Eno, I felt unable raise the matter of Brilliant Trees or their subsequent collaborations on its follow-up Alchemy: An Index of Possibilities, a cassette-only album of aurally questing instrumentals. He was, nevertheless, extremely keen to visit Maryon Park in Charlton, to see the locations from the film Blow-Up, a pilgrimage that would take him not a million miles away from the South London of Sylvian’s childhood.

Christened David Alan Batt, Sylvian was the son of a Lewisham plasterer. One employed, according to Simon Napier-Bell, Japan’s former manager who by 1984 was helping Wham! Make It Big as the title of their album had it, by Rentokil to fill in holes left by pest controllers. So this alumnus of Catford School For Boys had already been on quite a journey. Brilliant Trees, arguably, barely only hinted at the distance he would travel from hereon in. But as hints go it continues after all these years to impress me with its openness to musical exploration and fearlessness of pretension. His subsequent path, coming in fits and starts, from chart pop to full blown avant-garde experimentation and reclusive exile across the Atlantic, as has frequently been noted to the point of cliché, is most analogous to that of Scott Walker. Walker’s still bizarrely underrated 1984 album Climate Of Hunter, was also released by Virgin records just a couple of months before Brilliant Trees. There was a memorable, if slightly excruciating, sighting of the ex-Walker Brother, eyes-shielded by aviator-shades, promoting the record on Channel 4’s The Tube; a non-plussed Muriel Gray interrogating him on a sofa before the video for ‘Track Three\, involving a lot of swirling dust and a bald man darting about in a beaten-up old car, rolled.

Alongside the video for ‘Red Guitar’, Brilliant Trees, meanwhile, was to be trailed by an exhibition and accompanying book of Sylvian’s artwork. Entitled Perspectives: Polaroids 82-84, and staged at the Hamiltons Gallery in London that June, the show was comprised of collages most of them portraits (then girlfriend Yuka Fujii, Czukay, Sakamoto, McBean and Jansen with cat among the subjects) assembled from shots taken on a Polaroid Sun instant camera on his globe-trotting travels to Berlin (with its wall), Tokyo and beyond. Dismissed by some as little more than posh holiday snaps and compared unfavourably by art critics to David Hockney’s own Polaroid collages, the exhibition was profiled more positively in Smash Hits, where the article, endearingly, was teamed with an accompanying ‘Win a Polaroid camera’ competition for readers.

A touch naff perhaps. But it was by such eye-catching Radio 1 Roadshow-style giveaways that the likes of myself became acquainted with whole the notion of a contemporary art gallery and such infeasibly glamorous-sound things like ‘openings in Mayfair’, a place I knew only as the dark blue square on the Monopoly board with the hefty price tag. Sylvian has since questioned whether he’d been justified in ‘thrusting’ these pictures on an unsuspecting public, confessing that he’d just taken ‘a naive pleasure’ in moving into ‘other areas’, and described their creation as ‘an education’ for him. Whatever it taught him – and it’s hard not see comparisons between this visual output and the album’s compositions, with their layered textures, treated instruments and dictaphone samples – I certainly learnt a lot.