Decadence is an appropriately mutable and ambiguous concept. It can be used to signify the most contemptuous approbation, to suggest rottenness, decay, wasteful amorality and an utter disconnectedness from reality and shared social values. Yet without any real change in its meaning, the word can also be used in praising terms to suggest an alluring glamour, a wild, intoxicating freedom from society’s petty restraints and a sense of abandon and entitlement that is somehow admirable despite, or even because of, its obvious destructiveness. In some ways, decadence is about style over substance, and whether you view that as a sin; it’s the difference of opinion between the socialist and the dandy, and many of us struggle to balance these two conflicting positions within ourselves all the time.

More than on any other Bowie album in a career built on exploring the theme from any number of angles, the idea of decadence is at the heart of Station to Station. If Young Americans, his previous album, had examined the post-Watergate rottenness infecting the once-great nation he’d recently adopted as his home, then on Station to Station he turns his gaze fully inward upon his own condition, and finds the creeping decay at work there too. It’s a pre-punk album, not just chronologically (recorded in ten days at the end of 1975), but in recognising the hollow, bloated state of the rock aristocracy of which Bowie was a part, especially in contrast to the social upheaval and economic recession going on in the real world, wherever that was. Punk was a response from the kids on the street, but Bowie was part of the problem, and he knew it, tall in his room overlooking the ocean, staring out through a blizzard of coke and knowing it was all coming crashing down.

Ah, yes: cocaine. The proverbial Peruvian is all over this record, but not in an over-produced, airbrushed Rumours way. Station to Station is shiny but spare, harsh; it captures the jagged edge, the exquisite balancing act between the high and the comedown, and the sense of feeling hugely emotional at the same time as feeling completely numb and detached that is a typical symptom of fast white drugs (speed, E, coke). Similarly the intellectual grandstanding, paranoia and occultism, barely masking an inner desperation; having made a career out of wearing masks, inventing personas, analysing his emotions from a distance and then acting them out, Bowie seems desperate for a way out of his situation. Early in his career, under the influence of Lindsay Kemp, he made a short film called The Mask, in which a mime artist puts on a mask that then takes him over. By 1975 for Bowie the parable had come true. Lauded, wealthy, trapped in the social whirl of an affluent and fashionable Los Angeles jet set, reputedly existing on a diet of cigarettes, orange juice and cocaine and immersing himself in mysticism, conspiracy theories, the occult and an increasing fascination with right-wing ideologies, Bowie was fast becoming the epitome of the Decadent Man. Yet Station to Station is far from the work of an artist in decline. Rather, it extends the Philly funk of Young Americans into weirder, colder territory, and marks the beginning of the period of radical musical reinvention and rigorous introspection that would continue through the Berlin period and the more celebrated Low and "Heroes" albums.

Like the Duc Des Esseintes- the original Thin White Duke? – in Huysman’s 1884 novel A Rebours, Bowie has become jaded beyond belief, too numb and sated to be moved by any but the most extreme sensations. So far gone, so alienated from his own feelings is he that what he craves more than anything else is an authentic experience. Eventually he would realise this by stripping away all artifice and moving to Berlin, but here he still attempts to contrive genuine emotion, to convince himself by dint of a bravado performance. As if acting on ‘Young Americans’ celebrated line, "ain’t there one damn song that can make me break down and cry?" Bowie constructs the most grandiose of love songs, the most overblown, epic ballads, mouthing hollow romantic clichés as if, by saying the lines with enough simulated passion, he will actually come to feel them. And yet, of course, all of this is just a construct, too- he knows exactly what he’s doing. It’s not a cynical act, because the desire to feel remains genuine- in its way, this is as stark and troubled a record as anything from Neil Young’s contemporaneous ditch trilogy, the musical polish and role-play only thinly veiling a soul on the edge, battling with addiction and paranoia and with what he, at least, genuinely believed were dark mystical forces just waiting to drag him forever into the abyss. "It’s the nearest album to a magical treatise that I’ve written," Bowie has said, though perhaps a ritual spell of protection would be a more accurate description.

The album opens with the sound of a train. An old-fashioned steam train, chuffing from speaker to speaker and which always makes me think of Mr Norris Changes Trains by Christopher Isherwood- leaping ahead to Berlin, again – and then suddenly it isn’t a train anymore, but something far more warped and alien, and here come those flat, clip-clop piano notes, the spidery beat and Earl Slick’s strafing guitar feedback out of which a dragging, leaden riff slouches, some rough beast waiting to be born… But Bowie’s vocal is anything but rough: silken, demanding, ridiculously theatrical yet eerily convincing. ‘Station to Station’ isn’t about trains, despite being written while the notoriously aerophobic Bowie was touring America and Europe by rail; instead, it refers to the fourteen Stations of the Cross, which Bowie also equates to the eleven Sephirot of the Tree of Life in the Jewish Kabbalah- hence, "one magical movement from Keter to Malkuth," the songs most enigmatic lyric, which refers to the descent from the Crown of Creation to the Physical Kingdom, or from one end of the tree to the other.

This first section ends with a cryptic reference to Aleister Crowley’s early, poetic fusion of pornography and occultism, White Stains. A classic of decadent literature, Crowley himself later justified this short work as follows: "I invented a poet who went wrong, who began with normal innocent enthusiasms and gradually developed various vices. He ends by being stricken with disease and madness, culminating in murder. In his poems he describes his downfall, always explaining the psychology of each act." It’s not hard to imagine Bowie identifying with such a project, but before we have time to digest this, the whole song suddenly switches gear: not once, but twice, into hard, urgent funk with a proggy chord sequence, and then again, finally hitting that glorious plateau of a chorus and somehow staying there, like a never-subsiding orgasm, held impossibly aloft by Roy Bittan’s driving piano, just so long as you don’t look down- "It’s too late!" –Slick kicks in with a wired, fiery solo, and then, "it’s not the side effects of the cocaine- I’m thinking that it must be love," and we’re still up there, somehow- it’s a sustained, smooth-jagged coke high of a song, just keeping going, always up and on the one until it finally, inevitably fades out…

‘Golden Years’ is one of Bowie’s finest middle-of-the-road moments, a mainstream soul-funk ballad with mass appeal but a seriously weird core. It comes on like a love song, but what is it actually about? "Nothing’s going to touch you in these Golden Years (run for the shadows in these golden years)." It’s opaque, impenetrable, all mirrored surfaces and shifting moods. Again, the incessant, almost proto-rap delivery, listing things to do, balancing aggressive positivity ("Don’t let me hear you say life’s taking you nowhere") with brittle paranoia ("run for the shadows…") is pure coke babble, riding on the bright mellow glide of the groove and the dark empty spaces beneath… nothing’s gonna touch ya, move through the city, stay on top, all night long…

And Yet:

"In this age of grand illusion, you walked into my life out of my dreams…" What starts out sounding like a poignant love song suddenly becomes a doubting hymn, a tentative declaration of faith directed towards God above with no sense of irony or role-playing. That Lord’s Prayer moment at the Freddie Mercury tribute concert is alarmingly prefigured, as the penitent gak fiend drops to his knees on the studio floor (and a sudden shaft of light throws a shadow of a cross behind a conveniently positioned mike stand…). This song’s origins apparently lie in Bowie’s experiences filming The Man Who Fell to Earth, where certain unspecified dark doings on set led him to fear for his immortal soul. Working with Nic Roeg seems to have this effect on people: James Fox had a breakdown, found God and quit acting for years after working with the director on Performance, while Jagger was haunted by the role of Turner for years afterwards. Like Jagger in Performance, Bowie essentially played himself when portraying the alien visitor Thomas Jerome Newton, but soon found the role taking over his "real" life instead. Bowie began wearing a silver crucifix around his neck to protect him from occult influences, and ‘Word on a Wing’ finds him reaching out for some kind of belief that remains somehow just out of reach. The line "it’s safer than a strange land" draws parallels between The Man Who Fell to Earth and Robert Heinlein’s cult SF novel Stranger in a Strange Land. Throughout the early seventies Bowie spoke often of starring in a film adaptation of this book, about a messianic Martian who arrives on Earth, comes into conflict with the established church and is ultimately assassinated- obvious shades of Ziggy- but here Bowie seemingly renounces such Nietzschean self-determinacy in favour of the foxhole of orthodox Christianity.

‘TVC15’ provides light relief, of a sort; nobody’s favourite Bowie song, though the author seems to be having fun, and check the live version for a cringe-inducing example of rigorously-rehearsed spontaneity and looseness, a forced fake bonhomie among the band. It’s hard to say why it doesn’t work; certainly the brittle, cokey-hokey rush of words and the spiky piano jabs are in keeping with the rest of the album, but is it too frivolous-sounding in such heavy company? Or is the joke just too oblique for most listeners to get? Moving swiftly along, ‘Stay,’ apes ‘1984’ from Diamond Dogs, which itself purloined that dirty, funky wah-wah guitar sound from Isaac Hayes’ ‘Shaft’. Somehow though, the studio version never takes off for me, and this is one case where the live Nassau Coliseum version is far superior.

And so finally we come to ‘Wild is the Wind’, and who would’ve thought an old Johnny Mathis number would inspire Bowie to perhaps his finest ever recorded vocal performance? Also his most over the top and ridiculously affected, of course- try doing this one in karaoke and see if you can get away with it- but it’s the vocal that carries the song completely, turning what could have been a fairly plodding number into an epic finale to an already massively melodramatic album, on the back of little more than a strummed acoustic guitar, extremely spare bass and drums and some heavily-treated but low-key electric picking. Bowie’s vocal builds and builds, as the verses just repeat the same simple chord sequence, broken up by two deadened drum rolls that always make me think of Animal from the Muppets- until it finally just fades out, leaving you completely drained. "Don’t you know you’re life… itself?"

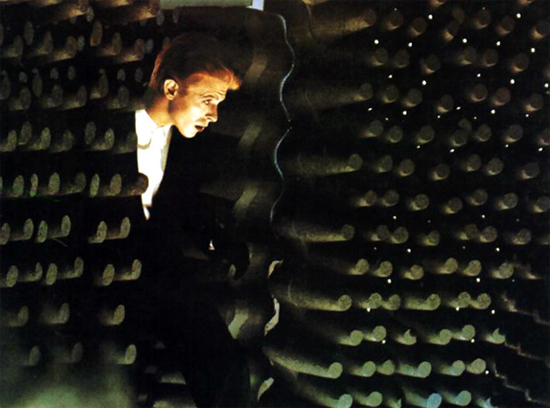

And that was it. Just six songs long, yet bestowing one of Bowie’s most enduring personas- The Thin White Duke, part Thomas Jerome Newton, part barking mad aristocrat from imperial Europe. Barely suggested on the album, he came to life on the subsequent tour, in front of a set inspired by Albert Speer and Leni Riefenstahl, in white shirt, black dress trousers and waistcoat, hair slicked back, frighteningly pale and thin, jerking across the stage in clipped, precise movements. An aging Ziggy, messianic fervour curdled into megalomaniac zeal, the scorned saviour turned armchair dictator, still mouthing hollow clichés of love and piety while quietly plotting bitter revenge. Bowie would have us believe that it was the Duke, not him, who gave the Nazi salute at Victoria Station and blathered on about how England would benefit from a Fascist dictatorship. And certainly, Nazism is one end product of a curdled, decadent romanticism, and a neo-Christian fascination with the occult, taken to irrational, nationalistic extremes. Personally, I’m prepared to accept that it was the side effects of the cocaine after all, and leave it at that. Happily, the album’s cold, claustrophobic funk and sense of dramatic tension would prove more enduring than the obsessions of its decidedly dodgy central character. Next stop- 1979, and early albums by Magazine, Simple Minds, the Banshees and Bauhaus, and many others in the post-punk, European canon. Station to Station, indeed.

Ben Graham on the reissue package

One might even suggest that in an era of enforced austerity, global recession, massive cuts in public spending, looming unemployment and an increasingly obvious gap between the haves and the have-nots, it is an act of decadence on EMI’s part to be releasing an individually-numbered 5-CD, 3-LP and DVD box set (also including 24-page booklet, poster, replica fan club pack, press kit, backstage pass etc- “the ultimate fan’s experience”) which, despite retailing for around £100, adds very little in musical terms to the original album which the target market will, without exception, already own.

Not that your humble reviewer received the entire deluxe package, of course; merely the five promo CDs in plain white inserts, all held together with a red elastic band that nicely replicated the colour scheme of the original record. The first two CDs feature said original album (no bonus tracks or outtakes) in two near-identical versions: the “original analogue master” on CD1, and the 1985 RCA re-master on CD2. The only difference, as far as I can tell – though I’m no audiophile – is that CD1 sounds slightly flat, while CD2 sounds slightly tinny. CD3 contains the single edits of five of the six album tracks, which are exactly the same, but hey- slightly shorter. And CDs 4 and 5 consist of a live recording of Bowie and band at the Nassau Coliseum on the 23rd of March 1976, trumpeted as “previously unreleased” but widely available on bootlegs for years; most famously, eleven of the fifteen tracks were packaged together with Bowie’s toe-curling ‘Young Americans’ medley from the Cher Show (see youtube if you dare) on the Thin White Duke double album.

I could write a whole separate review of the live CDs, but suffice to say that we’re a long way from the Spiders from Mars, and somewhere just east of jazz-funk hell; that the Dame goes through some half-dozen different comedy accents, often within the space of a single song; that they contain some of the most brilliant technical musicianship ever to be heard at a rock show, while also providing a dire warning of the dangers of putting three-chord garage rock numbers like ‘Suffragette City’ and ‘Queen Bitch’ – nice yodelling there, Dave – into the hands of over-achieving, coked-up musos; and that it features the most compellingly dreadful version of ‘Waiting for the Man’ ever executed, in which ‘The Man’ appears to be none other than that groovy cat Jesus Christ himself, my friends. You really should hear it; thankfully, it also comes packaged with the analogue master of the original album- that’s the slightly flat one- in the much more reasonably priced 3-CD version. It’s ridiculously, over-the-top brilliant and, yes, gloriously decadent.

Originally published in September 2010