There used to be a particularly evergreen tradition in the music press during the 80s and 90s: declaring David Bowie’s latest album the best since Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps). In fact this descriptor was probably used about every single album bar one: 1993’s low-key The Buddha Of Suburbia, which is ironic because this actually was his greatest album since Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps) and the benchmark by which his subsequent work should have been measured against.

And yet for all that, The Buddha Of Suburbia limped upon its release in late 1993 to a measly No. 87 in the UK album charts thanks to a combination of misunderstanding, misjudgment and mis-marketing. What should have been Bowie’s repositioning and return to his previous status as a solo artist of imagination and clout was instead sold as a soundtrack album with a cobbled-together cover that for the first time – in the UK at least – left its author out of the frame. Overlooked and ignored, The Buddha Of Suburbia was soon quietly deleted and not heard of again until its somewhat discreet re-release in 2007.

Seen from the vantage point of a quarter of a century since its original release, The Buddha Of Suburbia is both a consolidation of Bowie’s strengths as a singer, songwriter and producer, and a seed of what was to follow as he began to dig himself out of the very deep hole that he’d fallen into in the wake of 1984’s overcooked and underwhelming Tonight album.

Like many artists whose roots lay in the 1960s, the 1980s had been for the most part an unforgiving decade, yet by 1993 some of these cultural movers and shakers had found new voices with which to convincingly express themselves with again. His former sparring partner Lou Reed had reached an unexpected solo career high with the penetrating social commentary of New York, while Neil Young’s Freedom atoned for many of the sins he’d committed during the previous decade. Even Bowie’s friend and erstwhile flatmate Iggy Pop – an artist not known for consistency and reliability – had got his shit together on Brick By Brick, and had just released American Caesar, at that point his best post-Lust For Life album.

David Bowie’s fall from grace had been particularly hard to take. By making overtures to the mainstream, Bowie had lost that eldritch charisma, otherworldliness, dangerous sexuality and sense of threat that had been an integral part of his appeal. Not so much art as artifice, his stock fell further with the utterly bland Never Let Me Down and the overwrought Glass Spider tour that followed. And while Tin Machine’s first album had its moments with Bowie’s fingers seemingly on alt.rock’s cultural pulse, no one was really taking his new image as one of the lads seriously. Especially when dressed like a banker spending his bonus on pop & chop.

But it’s in that space between the two Tin Machine albums that David Bowie’s creative re-birth began to gestate. In sharp contrast to big hitters such as The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, Bowie took back control of the most lucrative part of his back catalogue and applied great care in re-purposing it for the oncoming digital age. Carefully re-mastered and repackaged to include B-sides and rarities as well as artwork befitting of the medium, his imperial period of the 70s was sold once again not only to those who’d bought it first time around, but also to a whole new generation over whom Bowie’s shadow loomed large. Preceding it was the Sound + Vision box set, one of the first of its kind and made all the more desirable with deep cuts and alternate versions previously unavailable in digital formats.

With Bowie marketing the accompanying Sound + Vision world tour as the last chance for fans to hear the hits, there was a feeling he was trying to draw a line as much under his 70s heyday as much he was the nadir of the 80s while trying to re-purpose himself for the 90s. Yet for all of his efforts, there still remained a sense of cynicism about the enterprise. The notion of a ‘Greatest Hits’ tour seemed anathema to what had come before it and its overt commerciality rankled, too. With a move that presaged his enthusiastic embrace of the internet later in the decade, fans the world over were encouraged to call a premium-rate telephone number to vote for the songs they wanted to hear for one last time.

Taking a skeptical view over Bowie’s last hurrah claim and subverting the voting methodology it employed, NME launched the tongue-in-cheek ‘Just Say Gnome’ campaign that urged its readers to vote en masse for his 1967 novelty single, ‘The Laughing Gnome’. Bizarrely, the campaign had been inadvertently kick started by Bowie himself. At the press conference launching the tour, NME’s David Quantick asked Bowie if he had any intention of playing the song at any of the upcoming gigs. To the surprise of those present, the singer picked up an acoustic guitar and strummed and sang the first half of the song’s chorus. Despite the magazine’s best efforts, Bowie failed to perform it on the tour. ‘The Laughing Gnome’ did, however, sneak into The Men They Couldn’t Hang’s set when they opened for Bowie at his two Milton Keynes shows. Though it was played on the first date, it was noticeably absent on the second night. Perhaps someone from the headliner’s organisation had a discreet word?

But even if Bowie was attempting to re-establish his credentials to make amends for some incredibly slight material, the feeling remained that he was fast running out of ideas and relevance. Moreover, his 1993 reunion with Nile Rodgers for Black Tie White Noise would be seen as retrogressive move, despite topping the UK album charts and spawning three Top 40 singles. And it would have to take something really special to make up for Bowie’s arse-clenchingly embarrassing reading of The Lord’s Prayer at the Freddie Mercury tribute concert the year before.

With a past as deep and wide as Bowie’s, it stands to reason that perhaps he’d been looking in all the wrong places to give himself the kick-start that he needed. It certainly wasn’t with the hit-making potential of Nile Rodgers (or ropey covers of Cream and, Gawd ‘elp us, Morrissey) and the brief reunion with his former lieutenant Mick Ronson, or the swaggering boys’ club of Iggy Pop’s former rhythm section, the Sales brothers. Or even his greatest hits, for that matter. Instead, Bowie’s rejuvenation came from an unlikely yet entirely appropriate source that took him even further back into his past.

The Buddha Of Suburbia’s inception came about not through calculation or cold planning but from a spontaneous moment of cheek. Taking part in a Q&A with writer Hanif Kureshi for the Andy Warhol-founded magazine, Interview, the author mentioned to Bowie that his Whitbread Award-winning novel The Buddha Of Suburbia was being adapted into a four-part TV serial for the BBC. Almost off-handedly, Kureshi asked if Bowie would compose the soundtrack. He quickly agreed.

The appeal of the project to Bowie would have been obvious. If he had been looking into his past to unlock his future, then he’d just found the key with a story that would have been loaded with considerable poignancy for him. Opening in the Bromley of the early 1970s, the book’s themes of searching for identity, the desire to leave the suburbs for the bright lights of the big city and the quest for stardom, as well as the cod-mysticism and sexual ambivalence that permeated the early part of the decade, were all topics that Bowie had more than a nodding acquaintance with. It wasn’t what he’d done that was the source of his inspiration, but the possibilities of what he was going to do.

The Buddha Of Suburbia arrived a mere seven months after the release of Black Tie White Noise. What makes this feat all the more remarkable is precisely what gives the album – and indeed, all of Bowie’s best work – its edge: a lack of time. Made in Montreux, Switzerland, the music was recorded in two distinct parts. The first concentrated on the soundtrack that was used in the dramatisation, while the second found Bowie developing some of the soundtrack’s ideas and themes into fully-fledged songs and pieces of music.

With the soundtrack done and dusted, Bowie returned to the studio with just co-producer David Richards (with whom he’d helmed Iggy Pop’s 1986 LP Blah, Blah, Blah – easily the best 80s album that Bowie had worked on) and multi-instrumentalist Erdal Kizilcay to begin work on what would become The Buddha Of Suburbia. And in an unexpected move, pianist Mike Garson would later come on board for the first time since 1974’s Young Americans.

In stark contrast to the time taken to make its predecessor, The Buddha Of Suburbia was recorded in just six days and then mixed in a fortnight. Reports suggest that the mixing would have been completed earlier were it not for some equipment failure in the studio.

At first glance, you’d be forgiven for thinking that the album was a rush job but consider this: all of David Bowie’s best work was created against the clock. His reputation for getting his vocals down in no more than two takes was already established, but his ability to write superior material to tight deadlines was equally as important. Even as far back as The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars, Bowie was able to deliver top quality music on the turn of a penny. ‘Starman’ – the 1972 single that broke him through to a wider audience – was written after the record label demanded a hit be included on the album. Similarly, ‘All The Young Dudes’ was created specifically for the soon-to-be-resurrected Mott The Hoople in double quick time after the band rejected his initial offer of ‘Suffragette City’.

Consider also Bowie’s work rate during the so-called Berlin years: four albums in less than two years in the shape of Low and ”Heroes”, and The Idiot and Lust For Life, his sterling collaborations with Iggy Pop. All the evidence suggests that when given the least amount of time to ponder his material, the better it was. It’s a theory that holds considerable water when looking at the best bits of his much maligned 80s period. Let’s Dance was recorded in a matter of weeks, ‘Absolute Beginners’ was assembled in just a few days, and his triumphant performance at Live Aid could’ve gone so horribly wrong given how little time he and his scratch band had to put the show together.

Conversely, Tonight’s failure was due in large part due to Bowie’s low boredom threshold. Having been asked to deliver up to 18 vocal takes per track, Bowie simply walked away from the project and left the production team to assemble an album of misfiring sleek pop and cod reggae. Elsewhere, despite its highlights, Tin Machine is too thought out and plotted to ultimately convince, while the less said about Never Let Me Down – which has just proved that an overhaul after three decades can’t save it – the better.

The Buddha Of Suburbia, then, is the sound of David Bowie not only reconnecting with his past but also with his muse and sense of musical adventure. Unencumbered by the weight of expectation or trying to second guess where culture might be going, Bowie shoots from the hip to hit his targets full square once again. This is an album that shares an aesthetic with the best of his Berlin period, most notably Low, as it mixes moments of melodic pop heights with experimental instrumental pieces and downright weirdness. In short, the Bowie of old here gets a much-needed re-boot for a new decade.

The title track that opens the album is a journey through the past in more ways than one. Reviving the melodic sensibility that informs his 70s work at its best, Bowie also makes two explicit musical nods to the days of his youth as ‘Space Oddity’ sticks its head around the door to say “hello”, with ‘All The Madman’ in tow for good company. Lyrically, the song finds Bowie pondering the stifling claustrophobia of his suburban background whilst sharing the concerns of societal repression and oppression that informed Pink Floyd’s landmark album, The Dark Side Of The Moon. These are the 1970s recounted through the eyes of someone who’d seen his chance and made the break, and the song is one of those rare occasions where Bowie becomes explicitly autobiographical.

Elsewhere, ‘Strangers When We Meet’ is quite simply one of the best songs Bowie ever recorded, period, let alone just from the 90s. A bootleg demo suggests the track was originally planned for Black Tie White Noise and it was certainly strong enough to be later re-recorded for 1. Outside, the album that followed in 1995. But the reading contained here is where it’s at; like Low’s ‘Be My Wife’ or ‘Everyone Says “Hi”’ that came nine years later, this is Bowie sharing his human side, someone who breathed the same air as the rest of us. Uplifting and joyous, it seems almost effortless. Likewise, ‘Untitled No. 1’, that’s infused with the kind of loveliness that had been in all too short supply from his work for far too long. Yet that said, Bowie can’t resist playing with his audience here: is he really referring to Bollywood actor Shammi Kapoor or is he signalling at something or someone else? And beneath it is a hint of the Indian melodies that permeated the multi-cultural suburban neighbourhoods of the 70s.

Nestled among these pop gems are the album’s instrumental pieces. ‘Sex And The Church’ is a perfectly accessible groove that suffers a little from a production that’s rooted firmly in its time. But there are moments of real strangeness and challenge. ‘South Horizon’ finds Mike Garson deploying some unhinged piano moves among what appears to be a potted history of jazz that gives way to contemporary moves before unexpectedly heading back in the direction that it came. And with Bowie digging into his past for more truffles, it comes as little surprise that both Low and ”Heroes” are recalled by the minimal ambient textures of ‘The Mysteries’ and ‘Ian Fish UK Heir’, that evoke ‘Subterraneans’ and ‘Moss Garden’ respectively.

What makes the album even more arresting is that Bowie is taking stock of his life and musical accomplishments and reinterpreting them for the new decade and for what is to follow. As he touches on glam, jazz, funk, ambient soundscapes and pop, he doesn’t so much produce a facsimile of what went on before as recalibrate his motives for creating music. Consequently, The Buddha Of Suburbia is the closest Bowie comes to presenting an autobiographical work, at least until the arrival of Blackstar just two days before his death in 2016.

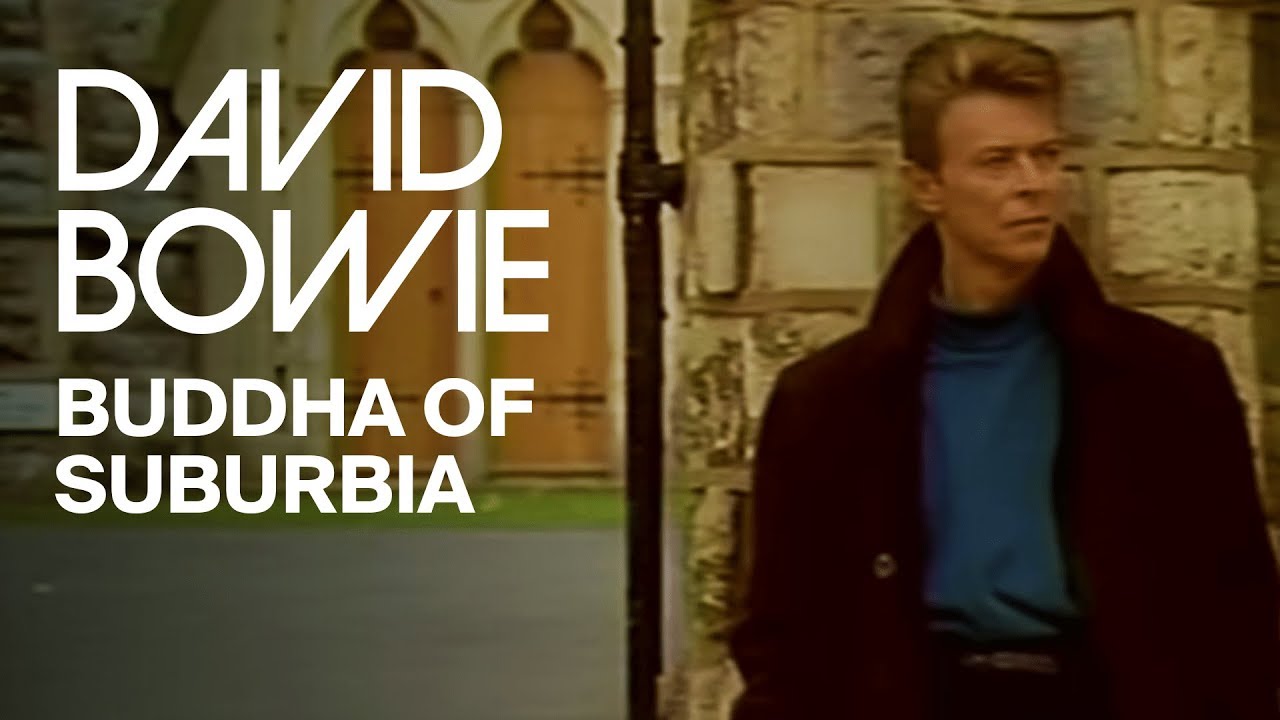

As evidenced by the accompanying video to the album’s title track, this was Bowie wiping the slate clean as he went deep into his origins. Shorn of image and any of the number of masks and disguises that he’d worn over the years, this is a non-descript Bowie. Dressed simply in an overcoat, polo neck jumper and baggy trousers, he almost loses his identity as he walks the kind of ordinary, suburban street that could be in any town in any county in the country. With no traffic and no people, the sense of stifling privacy, disconnect and alienation is palpable. And here we see Bowie returned to his roots as he sits in a suburban lawn strumming an acoustic guitar.

Writing in the liner notes of the 2007 re-issue, Bowie says of the record, “My personal memory stock for this album was made up from an almighty plethora of influences and reminiscences from the 1970s…” before listing the suburbs of Bromley and Croydon, as well musicians such as Kraftwerk, Pink Floyd and Neu!, before moving on to venues like Ronnie Scott’s and key artistic events.

And yet despite what was clearly a project that meant a lot to its author – he claimed in 2003 that it was his favourite album – The Buddha Of Suburbia tanked, and the reasons for this are still shrouded by a veil of mystery. Marketed as a soundtrack album and wrapped in a cover that looked as if it had made by an intern during a coffee break, The Buddha Of Suburbia suffered from a presentation that made it look like a work of little substance. Attempts to get to the bottom of this marketing disaster have been met with silence, though one Bowie insider – speaking to tQ on condition of anonymity – not only confirms how dear the record was to the singer, but also that he planned to play the album in full alongside 1979’s Lodger at a series of select concerts, much in the style of his 2002 revisiting of Low. According to the source, the plans were shelved after he curtailed his touring activity in the wake of the heart attack he suffered during a gig at the Hurricane Festival in Germany in 2004.

The suspicion lingers that Bowie’s hand had waved the album through as was as he began to eye up his next project – working once again with Brian Eno on what was to become 1. Outside. The lack of interviews around The Buddha Of Suburbia suggest that, perhaps because of the personal nature of the album, Bowie had said all that he’d wanted to through the music and now, with his palette cleansed and his mojo revived, it was time to move on. Furthermore, Eno’s contribution at transforming U2 from heartland roots fetishists into a contemporary rock behemoth flying in the face of the mainstream can’t have escaped his notice. Not least as Eno was tapping into his own Berlin experiences with Bowie as a reference point.

Even after 25 years, The Buddha Of Suburbia is a strange anomaly in David Bowie’s back catalogue. Both ignored and misunderstood upon its release, the album’s re-emergence in 2007 was met once again with very little fanfare and it remains the album that so few Bowie fans have heard of, let alone listened to. As such, The Buddha Of Suburbia is an album ripe for discovery, not least as it contains an approach and execution that not only captures the best of Bowie’s past but also kick starts his future. And in 1993 and for almost 10 years afterwards, The Buddha Of Suburbia really was David Bowie’s best album since Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps). It’s time that was acknowledged.