There are records that crystallise genres, there are albums that carve out new spaces in established scenes, and there are LPs that, over time, end up symbolising the era in which they were created. They’re relatively few and far between, they’re special and they’re rightly celebrated – but there are enough of each to provoke most music fans into endless list-making and debating. Records that create a new musical language, though? Those are rare.

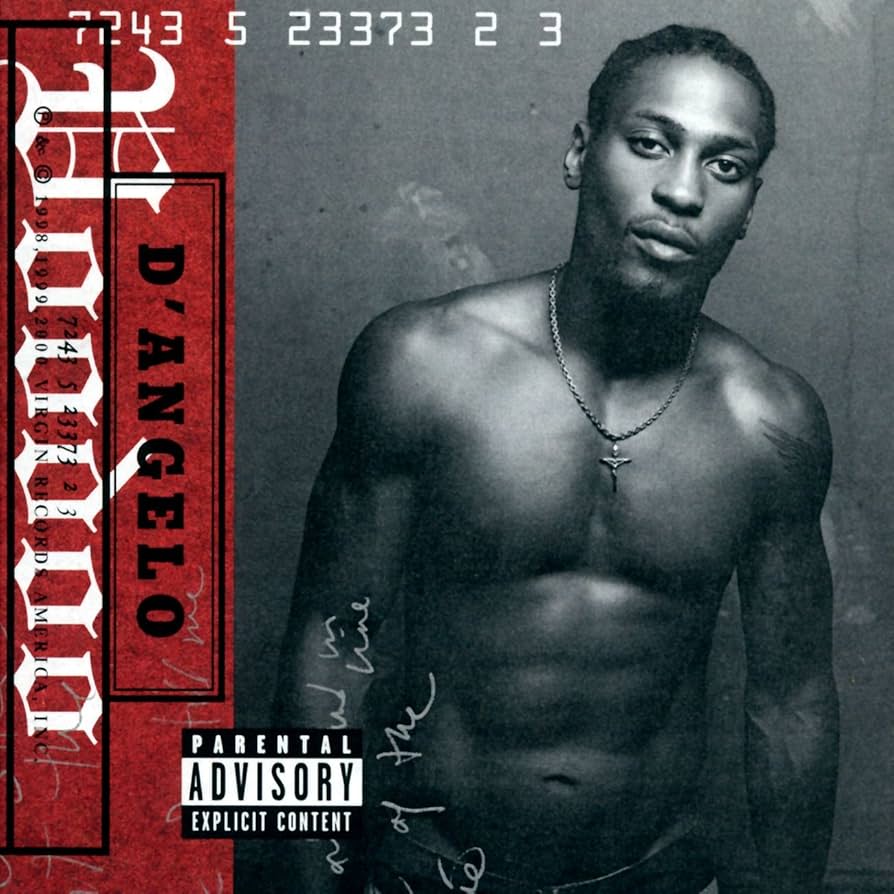

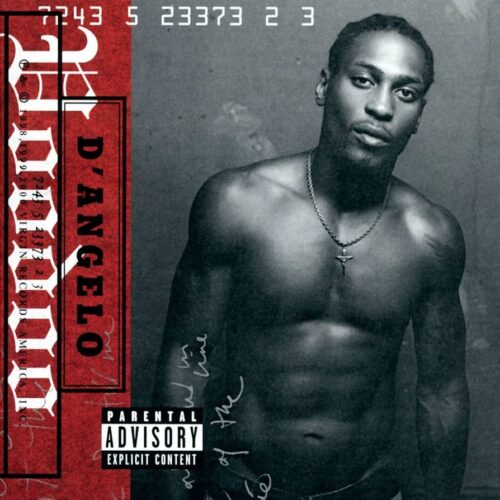

One record that did this was D’Angelo’s second LP. Feted on release, a regular in every “best album of the noughties” chart with any realistic claim to relevance published in the quarter-century since it came out, and an acknowledged inspiration to an unprecedentedly broad range of musicians ever since, Voodoo is even more remarkable than such music-fan statistics may suggest. The storied product of a three-year gestation, driven by an artist who was unwilling to settle for something that was merely good while he knew that the undeniably great was within reach, the album is a lodestone – exerting an almost gravitational pull on generations of musicians who have grown up under its direct, second, third and further orders of influence.

Remarkably, it’s a record self-consciously derived from a deep and detailed study of the music of the giants who came before, yet it never sounds like an act of homage; indeed, there is a case to be made that it is so determinedly individual as to be sui generis – an album built in acknowledged thrall to the past by a team who found ways to turn all their research and love of the music that preceded them into something entirely new. It’s homogenous almost despite itself – a coherent, consistent and distinctively individual creative world built out of parts as unlikely as an opening song that began life as a song inspired by kids’ cartoons and basketball and at least two tracks written and brought to demo stage for other artists. Its influence has extended from the immediate circles of those involved in making it and rippled out over continents and decades, its innovations still turning up on distant musical shores today. Its title evokes religion, folk traditions and magic – and as much as it is a work of a group of master musicians operating at the peak of their powers under the direction of a creative visionary, it also offers documentary evidence that there is something mystical, unknowable yet undeniably, tangibly powerful that can happen when people, ideas and extraordinary creative capabilities are brought together and allowed to find their own new ways to combine.

The story of Voodoo‘s creation has been told often enough to have passed in to modern musical folklore. It was the record for which the team that later, and somewhat contentiously, came to be known as The Soulquarians were first assembled. Between 1997 and 2002 the collective camped out at Electric Lady, the New York studio built for Jimi Hendrix in a former Greenwich Village nightclub, and made seven masterpiece LPs (eight, if we include Bilal’s still unreleased Love For Sale) that redrew the notional boundaries that many people chose to place around hip hop and soul.

At the heart of the innovation incubated was what those involved termed “treats” sessions: instigated by the inveterate collector-fan Questlove, these were informal but intense periods of studying, usually, VHS copies of long-lost TV broadcasts showing giants of soul, funk and the more interesting ends of rock. The treats would combine in Electric Lady’s singular atmosphere with the history and legend that fell out of the ceiling-mounted air-conditioning ducts and oozed from the fixtures and the equipment – not just recording gear used by Hendrix and microphones that (probably) captured Bowie’s vocal for ‘Fame’, but a Fender Rhodes that Stevie Wonder used when he recorded Talking Book and murals that would have looked down on Patti Smith’s creative duelling with John Cale during the making of Horses and drum screens that may have surrounded Billy Cobham’s kit when he recorded Crosswinds.

A typical day at Electric Lady in 1998 would have started late afternoon, with Quest unearthing the treat of the day: then he and D’Angelo, and whoever else was around – sometimes Quest’s fellow Roots associate, the keyboard player, producer and composer James Poyser; Pino Palladino, the prolific Welsh bass player D’Angleo hired as a personal latterday James Jamerson; or Detroit producer/rapper J Dilla – would watch and rewatch footage of the people D’Angelo termed “the Yodas” – Prince, Hendrix, George Clinton, James Brown, Sly Stone. Then, imbued with the treat’s promise to the point of almost being intoxicated by its influence, they’d jam until the early hours, taping everything, occasionally asking engineer Russell Elevado to play a section back to see what it was they might have unearthed, or channelled. And from those moments the songs began to emerge.

If the process sounds as if it was somewhere between mythic and mystic, there’s little wonder the same is true of the resulting recordings. Just about the only criticism many reviews and reappraisals of the album make is that there are frequent passages where D’Angelo’s vocals – a mellifluous, multiply overdubbed, cascading chorus of breathy exhortation and feather-light falsetto – drift in and out of comprehensibility: but to these ears, that just deepens the sense that the Voodoo sessions went beyond the recording of an album and succeeded in capturing the performance of a sacred rite. This is music with oceanic depths; the mysteries wouldn’t be mysteries if they could all be easily solved. Yet not only do these songs coalesce around such blurry notional focal points, they sit inside what feel like gently enveloping, meticulous yet loose and almost haphazard musical beddings. A descriptor often invoked is “woozy”, and there is certainly a sense of intoxication here: but this is a record that never feels like it was made under the influence of a drug or a drink. This is a work of the kind of dislocated ecstasy that only seems to really exist in a religious context.

In his fascinating and exhaustively researched 2024 book Two-Headed Doctor, David Toop brilliantly unpicks the notionally mystic roots of Dr. John’s 1968 debut Gris-Gris. While Toop’s work suggests that album may not be the result of its makers being as under the influence of forces from beyond the observable universe as they might have wanted listeners to believe, Gris-Gris nevertheless remains a record that wears its mysticism well and transmits a sense of the otherworldly to the listener. It doesn’t appear to have been mentioned by any of the principals as a direct influence on Voodoo, and certainly, with no TV exposure to speak of, it’s unlikely any of its tracks would have been among Questlove’s library of treats. But – despite what Toop identifies as the artificiality of much of Dr. John’s evocation of ritual and magic, and the very evident way that same effect is arrived at intuitively by D’Angelo – in many ways Gris-Gris feels like a notably close relation. It isn’t just the title, or the existence of a permanent pervasive evil that has to be overcome in ‘Devil’s Pie’, or how the lyric of ‘Chicken Grease’ nods to folk traditions even while quoting Rakim and hymning the timeless mystery of musical creativity, or even the way that the aching beauty of ‘The Root’ turns out, once you get over the gorgeousness of the form and begin to let the meaning seep in, to be not just a song about being helplessly in love but being literally put under a spell by your lover – though it’s all that, obviously. But it’s there in the ways both these records were created – extended teams, freed from many of the usual time-poor/budget-first constraints placed on artists by record labels, using studios as both playground and laboratory – and in the decisions taken to foreground both the consummate skills of the musicians with a final recorded form that presents the songs almost as sonic puzzles that listeners are able to pore over for years, finding new possibilities and new interpretations even after decades of listening. Both records are gifts that seem unable to stop giving, and both, as a result, exist almost out of time.

Voodoo‘s influence was immediate and has been uncommonly enduring. The obvious early beneficiaries were D’s fellow Soulquarian collaborators, firstly The Roots, whose blistering Things Fall Apart beat Voodoo to the record shops despite much of it not being conceived until after the D’Angelo sessions had begun.

Questlove has been consistent and fulsome in crediting D’Angelo and J Dilla not just with many of the sonic innovations on Voodoo but on challenging him to become a different kind of musician. Dilla’s ability to use samplers and sequencers to create sounds and rhythms that were sloppy in ways that machines can never be was, at first, confounding to a drummer who, sensitive to criticism that his live playing wasn’t sufficiently sample-like, had hitherto striven for a metronomic consistency that would rival an 808. He’d only just felt like he’d perfected this – in his sleeve notes for Things Fall Apart he highlights the song ‘Double Trouble’ as being “my proudest moment” among all the tracks he’d drummed on to that point, having finally identified and mastered all the elements he needed in order for his playing “to sound more like an old school Marley Marl joint… as opposed to a Brand New Heavy joint”. For Voodoo he had to undergo a process he would later liken to a “de-programming”, learning to play ever so slightly off the beat – often just behind, sometimes a little ahead, generally a bit of both in the same song.

That’s not to say that there aren’t moments where the conventional is required, and delivered. The cover of the Eugene McDaniels-written, Roberta Flack-recorded ‘Feel Like Making Love’ provides a kind of a key the unprepared newcomer can use to begin to unlock some of Voodoo‘s hidden rooms. It’s the most straightforward track here, and because it exists in a beloved earlier incarnation, it’s possible to use it as a scale against which to measure where D’Angelo and friends desired to take their music, and to help understand where their art would still cleave to accepted and understood codes and modes of creativity. There’s very little in the drumming that suggests the off-kilter dislocation much of the album deals in: instead, here, that is supplied by Palladino’s bass, which spends much of the tune running Quest’s drumming down, never far behind but never in any hurry to catch up. Similarly, Roy Hargrove’s trumpet – recorded on vintage ribbon microphones found, dusted down (literally), then repaired and renewed by Elevado – sounds as if beamed in from a distant star system. This is the track that was supposed to have featured a guest appearance by Lauyrn Hill – due to return the favour to D’Angelo for his appearance on The Miseducation…’s ‘Nothing Even Matters’ – and there will always be reason to lament that that collaboration never took place. But there is something grounding about having this one moment on Voodoo which the listener can use to perhaps get a sense of the scale of the creative endeavour the rest of the record represents.

Beyond the clutch of brilliant records from the same extended family that followed Voodoo out of Electric Lady in the early years of the century – Erykah Badu’s Mama’s Gun, The Roots’ Phrenology, Bilal’s 1st Born Second and Common’s Like Water For Chocolate and Electric Circus – the next closest relative, to these ears, appears to come from a quarter many would likely feel unexpected. While working on his second LP in 2002-3, John Mayer enlisted Questlove and Hargrove to play on the opening track, ‘Clarity’. To that point pigeonholed as a pop-rock singer-songwriter, Mayer’s first love was the blues, and his next project was to inaugurate a trio to explore a more primal form of electric blues, for which he recruited Palladino and the hugely experienced drummer Steve Jordan. His third studio album, Continuum, found Jordan co-producing and playing, Palladino on almost every track, and Voodoo rings loud and clear pretty much throughout – even in the spaces and silences. The influence is arguably at its most pronounced on the song ‘I Don’t Trust Myself (With Loving You)’, where Palladino’s bass stalks the beat just as he had done on D’Angelo’s McDaniels cover, Mayer overdubs his own vocal for the gently echoing hook, and then, just short of halfway through, Hargrove is deployed for a signature three-note motif. There’s even a track featuring, and co-written by, the incomparable Charlie Hunter, whose custom-made eight-string guitar allows him to play bass and guitar parts simultaneously – as he had done to striking effect on Voodoo‘s glorious ‘Spanish Joint’.

You can play endless games of join-the-dots connecting more or less every interesting or innovative development in soul music over the course of the 21st century back to Voodoo, but it’s the record’s impact outside what might ordinarily be thought of as its expected spheres of influence that really speak to its impact, its importance, and what other musicians are quick to revere as its evident excellence. Mayer is exhibit one when arguing this case, but by no means a solitary outlier. Sometimes it’s not just albums or artists that reflect this record’s brilliance, but entire genres: certainly, it’s difficult to hear many of the vastly different and creatively divergent artists active in Britain’s current jazz milieu without being put in mind of Voodoo and its approaches to composition, production and performance. London’s Jazz Cafe has chosen to mark Voodoo‘s 25th anniversary with a performance by a group led by Blue Lab Beats’ Mr DM, emphasising the connection between D’Angelo’s album and the new wave of British jazz artists; Voodoo is included in a concise “further listening” list in the booklet accompanying 2023’s brilliant, genre-defying Dave Okumu and the 7 Generations album, I Came From Love. But its impact is just as strong even when it is nowhere near so explicit or acknowledged: it’s there in many of the new British school’s slouching feel for shapeshifting rhythm, a favouring of the human over the mechanical which nevertheless leaves room for the electronic and the experimental (leading to decisions over tiny details – such as the adoption of stacks of bent cymbals to allow a drummer to play a drum-machine-style handclap – to become increasingly essential elements of a style); even just the celebrating of a wider creative community that means it is no longer unusual (at least among that scene) to find albums and gigs featuring peers who, in other genres and eras, might have been rivals, working together to help each other create art that will surely stand at least as stringent a test of time.

Perhaps these British artists are also as familiar – whether directly or indirectly – with Lewis Taylor’s magnificent self-titled 1996 LP, which arguably beat Voodoo to a couple of its punches. Taylor’s ‘Damn’ plays the same trick as ‘Untitled (How Does It Feel)’ (the single that sent Voodoo supernova and which, along with its extraordinary video, appears to have been the main factor that led to its creator needing to take a decade and a half before being able to finish a follow-up), slow-burning to an almost unbearable emotional crescendo before abruptly cutting off the tape mid-flow. But beyond that, Taylor’s album seems to predict some of Voodoo‘s enveloping atmospheres. D’Angelo was a fan and Taylor was, infamously, invited to New York to take part in the Voodoo sessions, but, after two nights in a hotel waiting for a call to the studio that never came, he lost patience and booked himself on the next flight home. Of course, Lewis Taylor was released a year after D’Angelo’s debut, Brown Sugar, so the influence would surely have worked in both directions: but with Taylor’s background in, and further subsequent explorations of, psychedelic rock, it has to remain one of music history’s more beguiling ‘what if’s to wonder at the unexplored regions of Hendrixian creativity which might have been mapped had someone from D’Angelo’s camp remembered to pick up the phone.

But never mind the things that didn’t happen, the tracks that weren’t written, the developments that didn’t take place: what’s here remains remarkable, innovative, rich in substance and resonance, still every bit as capable of enveloping the listener in its ecstatic embrace, of beguiling with its innovation, of captivating hearts and souls with its enduring magic and mystery.