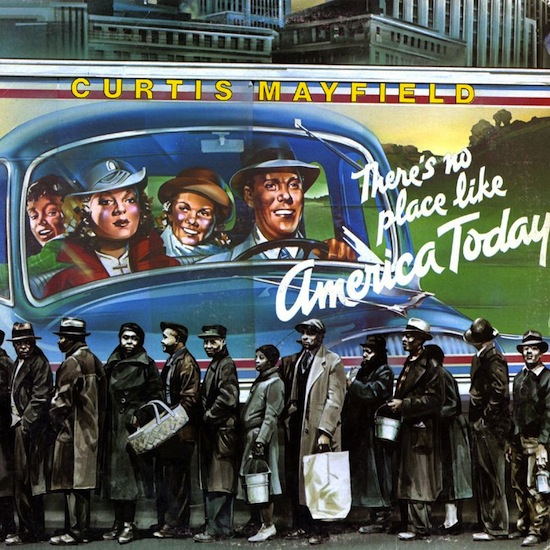

The picture is justly famous; although, like many pictures which resonate with their time, the true circumstances of its origin differ somewhat from the projected message. The camera never lies, but it equivocates.

A line of figures queues across the frame on the big-city sidewalk, all of them overcoated and be-hatted, many carrying baskets, buckets or bags, every one of them black. One or two eye the camera, maybe with curiosity, but with no friendliness or approval. Others look uneasily away from it or pointedly, resentfully ignore it. Yet others are simply unaware of the spying lens. They look ahead or nowhere in particular, faces unreadably glum – except for one man who seems to smile at a private thought. Each has the air of someone forced to endure what should be a personal moment in public, reacting with shame or anger, defiance or resignation.

The picture must date from the Thirties, evoking as it does the Great Depression. Obviously, these people are awaiting a handout. Equally obviously, this is the last resort for them. They look like solid folk, driven by circumstance, by the failings of a callous and careless economic system, into the door of a soup kitchen.

In fact, history never being so helpfully pat, they are victims of the weather, lining up for flood relief. The picture tells an entirely true story of its era, and of race in the USA, much as photographs from Hurricane Katrina do. It just so happens it might as easily date from the boom-time Twenties for all it has to do directly with the Depression – were it not for the punchline, the compelling irony that drew the lens and made the image a classic. Behind and above the line of unwilling supplicants, dwarfing them and devouring the centre of the photograph, stands an enormous billboard. A smart little car, hugely magnified, charges out of from the hoarding straight towards the queue. Inside it, a smart little white family, wholesome – loathsomely so, to today’s eye – grotesquely clean and happy, smile in wonder and delight at the bleak vista below. (All bar the mother, who wears an expression of smug arrogance worthy of any Third Reich fraulein.) Across the poster, in exuberant, climbing letters, runs the slogan: "There’s No Place Like America Today".

Recreated, in tinted form, from Margaret Bourke-White’s 1937 monochrome original, ‘At The Time Of The Louisville Flood’, and with the original advertising slogan adapted from "There’s No Way Like The American Way", this is the cover of Curtis Mayfield’s album of the same name. He couldn’t have picked a more apt one; the record evokes its own time and place as surely as the picture represents the chasm between American dreams and street-level reality. 1975 was, for many in the cities of the USA, a particularly wretched time, one which even now carries the aura of winter, of hangover, of chills and meanness and struggle.

America’s mid-seventies are best remembered for their political events. The Nixon administration had packed up its tent to the accompaniment of national derision and delusion. The music and art, the journalism, films and novels of the moment reflect shock and disenchantment and outright paranoia – this last being one of Richard Nixon’s own particular contributions – following revelations that the government of the USA had acted in ways that would have given the Cosa Nostra, if not sleepless nights, then at least a few handy pointers.

But to many people, that didn’t matter a damn. They had never expected anything better from the government anyway. What Nixon and his goons were up to was of far less import than the recession into which America had slumped. And those who felt it first and hardest were America’s urban blacks, in towns such as Detroit, where the car industry was concussed by huge oil price rises. The message of Mayfield’s album cover was clear. Forty-five years on, and what’s changed? Civil rights marches, changes in legislation, voting rights, LBJ’s efforts to revive FDR’s Great Society, and what’s changed?

Mayfield is best known as a master of fluid funk; as the creator of every funk-lover’s favourite song ever, ‘Move On Up’, and thus as a positive and inspirational force; as a Blaxploitation soundtrack genius and consequently a seriously hip figure in the pantheon of Seventies music regenerated as style; and as a major influence during the early, pimpmobile days of Gangsta. (Ice T freely acknowledged that he was up to his armpits in hock to Mayfield.)

Few remember him as a chronicler of austere times. Subtle and seraphic lovejuice maestro Marvin Gaye takes due credit for his ravishing and less sophisticated political opus, What’s Going On; but There’s No Place Like America Today seems to be missing from the canon. Mayfield is generally accorded his due, but one seldom sees mention of this particular record. A shame, because it’s a masterwork.

There’s No Place Like America Today is a record of its time, which has its own fascination; but it’s also an album of timeless intrigue. The world it portrays is very cold indeed, and the comfort it offers is as spare as its measured, melancholy funk. But it’s comfort nonetheless, something buried so deep in the music that maybe those of us whose bones have never ached, day in, day out, on hard city streets – and good for us, I say – can’t really get to grips with it.

Mayfield’s music is as restrained and insinuating on There’s No Place Like America Today as it would ever be. His fluting falsetto, rather than being carried on the tide (as it was on ‘Move On Up’ et al), draws the instruments behind it. There are no breaks, no crescendos. The album never loses its mood of gentle insistence. It may be most sombre funk record ever made, which doesn’t sound like much of a commendation. But it isn’t sombre in the manner of, say, the grey-coated, white cerebro-funkers of the early Eighties. It’s not heavy, dour or miserable. It’s light on its feet, delicate, but no less serious for that. It sounds like an honest response to the mood of its times – Mayfield may have felt that he could hardly sound the call to party when so many of his audience were finding it difficult enough to get though the week.

THE opening number of There’s No Place Like America Today sees a convict, on the day of his release, find out about the shooting of an old friend, the ‘Billy Jack’ of the song title. The track, far from resembling a dirge, takes the form of tremulous piece of butterfly funk, as if Billy Jack’s death were too predictable an event to be truly mourned: "Too bad about him – too sad about him/Don’t get me wrong – the man is gone/But it’s a wonder he lived this long." In almost miraculously concise fashion, Mayfield tells you everything you need to know about Billy Jack: "Up in the city they called him Boss Jack/But down home he was an alley cat/Ah! didn’t care nothin’ bout bein’ black." And now he’s dead, plugged in some petty criminal exchange. The whole history of the man is contained within; you could take that cameo and write a life from it. But first you’d have to tear your attention away from the song itself, which is as tight and irresistible as any of Mayfield’s more upbeat work. As well as being as musical titan on the basis of his songwriting and record-making, Mayfield was an astonishing guitarist, with a style so cunning and fluent that attempts to copy it have often go clumsily awry.

‘When Seasons Change’ could be the keynote address of 1975; so much so that temptation is to simply reprint the entire lyric and leave it at that. Certainly, it’s the thematic cornerstone of the record. The onset of winter, the struggle to survive, the cold landscape, riddled with predators. "A lot of scars – the kind that scare you to remember/Scuffin’ times – in seeing people trying to put you down/For goodness sakes/People trying to take what you know that you’ve found." But, as throughout There’s No Place Like America Today , Mayfield shows no interest in attributing blame for the harsh situations he describes- or perhaps, rather, he considers the primary source of the trouble so obvious as not to require pointing out. The reproach to the powers that be is as strong and implicit as it is in the album’s cover image. But if there is a message at the heart of the LP, it’s "Look to yourselves." Even in ‘Jesus’, he points to Christ not with pie-in-the sky religiosity, nor as the traditional source of divine love in adversity, but simply as a human role model: "He never had a hustlin’ mind/Doin’ crime – wastin’ time."

‘Blue Monday People’ and ‘Love To The People’ follow the same idea, of seeking strength and warmth in the hearts of yourself and others. For a political album – and There’s No Place Like America Today is deeply political, if unspecifically so – this is a remarkable premise, one on which Mayfield had been building since his sublime and generous Impressions song, ‘Choice Of Colors’. His message appears to be: Yes, things are terrible, and through no fault of your own; but how will you respond? What will you choose? We will sink or swim together, Mayfield always insisted; the same message that he had put in more scathing fashion five years previously on the magnificent, apocalyptic ‘(Don’t Worry) If There’s a Hell Below, We’re All Going to Go’.

From any more privileged quarter this would unquestionably be odious bootstrap piffle. Mayfield has a right to ask the question, though, brother to brother, as he so often did. It’s almost as though we’re listening in on a private conversation.Maybe this makes No Place Like America sound as if it’s a preaching kind of album. That’s not the case. It’s much less so than What’s Going On, for instance. There’s nothing didactic in the tone of the record. That never was Mayfield’s way.

‘Hard Times’ is nothing more than what it appears to be; a lament for the collapse of decency, and the downward spiral of black-on-black violence. Although it’s never openly stated, No Place Like America portrays the comedown from the Sixties. For affluent white kids, that decade may have meant peace and love (ie. plenty of drugs and unlimited opportunities for boys to sleep with girls too frightened of appearing repressed to complain about bad and/or unwanted sex), and the chance to play at being revolutionaries. For blacks, it meant political and social gains on a previously unimaginable scale; gains that by 1975 seemed to be reversed, in practice, at every turn. True, some of the promises of the Sixties were fulfilled; America has developed a large black middle class, a process which was well under away by the mid-Seventies. But it was those left behind who were the subject of Mayfield’s album – the Seventies equivalents of the hard-worn folk on the cover, whose own present day successors have no reason to feel much differently. There’s No Place Like America Today is a record of its time, all right, but it’s a sad fact it is also a record of ours.

From beginning to end, There’s No Place Like America Today trickles like cold quicksilver. It feels deft and spare, which is curious, as it’s not a minimal album; arranger Rick Tufo was lavish with the strings and horns. There is no drama about it, no wailing or wringing of hands. It is deeply funky. As on all of Mayfield’s records, nothing is wasted. No surplus flesh. That it should be so low-key, so understated, that it should deal unflinchingly with such a desolate theme and still be such an affecting source of pleasure, is as fine a testament to Mayfield’s genius as any of its better known predecessors in that extraordinary run of great releases to which it proved a coda.

This article has been adapted by its author from a piece in the 1995 Melody Maker book Unknown Pleasures