Come along with me tonight

I’ll take you down my subterranean lair

Come on right now

It’s right down there…

Lux Interior, ‘The Tube’, 1984

The overriding narrative arc of The Cramps is the near four-decade romance of Lux Interior and Poison Ivy Rorschach. But this also ties in to their unswerving love affair with rockabilly, garage rock, psychedelia and a whole host of trash aesthetics that informed their music. Their story also relied on a cast of supporting characters who enabled them to bring their musical vision to life. Their tale began in 1972, when 25-year-old Lux Interior picked up 19-year-old hitchhiker Poison Ivy (although back then they were still Erick Purkhiser and Kristy Wallace) in Sacramento, but it wasn’t until they moved to Manhattan in 1975 – drawn by the noises emanating from CBGB’s – that things really began to take shape, almost by accident.

Lux took a job at the Musical Maze record store and soon gravitated towards co-worker Bryan Gregory (formerly Greg Beckerleg) who, despite having no musical ability, was asked to join Lux and Ivy’s nascent band. Through a misunderstanding, Gregory bought himself a guitar instead of a bass and, more through embarrassment than anything else, didn’t point out his mistake. And so the twin-guitar-no-bass musical attack of The Cramps was born. It’s often these fortuitous mistakes that make for great music. Would John Cale have bothered to read Lou Reed’s lyrics to ‘Heroin’ were it not for the guitarist’s unconventional method of ostrich tuning? Would The Jesus And Mary Chain have got anywhere if William Reid’s faulty fuzz pedal hadn’t let off unwieldy shards of feedback? With The Cramps, Gregory played heavily overdriven basslines on his six-string guitar so Ivy could take flight, and they chanced upon the sound that became their early calling card.

After brief stints from drummers Pam Balam (Gregory’s sister) and Miriam Linna, The Cramps’ rhythm section was cemented with the arrival of former Electric Eels man Nick Stephanoff, who quickly adopted the surname of Knox and fleshed out the sound the band was striving to attain while adding considerable gravitas to their image.

"We wanted to be as shocking, sexy and original as the great culture changing rock & roll pioneers were during the 50s and 60s," wrote Lux and Ivy in the sleevenotes to the retrospective How To Make A Monster. "Not imitators, but the same kind of rebels that they were in their time." Such was their dedication to their singular cause – eight studio albums, two live albums, two compilations of early singles and a collection of early demos and live material – that it’s much too easy to overlook their contribution. Much like the Ramones, they didn’t deviate from their formula; they stuck rigidly to what they loved best – unashamedly sleazy and downright thrilling rock & roll that shot from the hip and didn’t even bother to ask questions later. Little wonder, then, that when Lux sang, "I don’t know about art but I know what I like," on 1983’s ‘I Ain’t Nuthin’ But A Gorehound’ it sounded more like a manifesto than an excuse. But unlike the Ramones, The Cramps found themselves purged from CBGB’s history books despite making their debut appearance there supporting the Dead Boys in 1975 and continuing to play at the venue in the years that followed (as well as introducing Da Brudders to The Trashmen’s ‘Surfin’ Bird’).

Of course, it’d be erroneous to suggest that The Cramps never progressed with their sound. Over the course of their lifetime, the line-up eschewed the dual-guitar attack in favour of a more conventional bottom end and an ever-changing cast of bassists and drummers who each made their mark around mainstays Lux and Ivy. Moreover, Ivy’s increasing talents as both guitarist and producer ensured that latter-day cuts such as 1997’s Big Beat From Badsville packed enough wallop and sonic force with songwriting chops to maintain interest. But it’s those early albums – Songs The Lord Taught Us, Psychedelic Jungle, Smell Of Female and singles compilation Off The Bone, that continue to lure like a siren’s call – and for good reason. This is the sound of a band laying down its blueprint by delving into rock & roll’s primordial origins and mixing it with psychedelic drugs, horror movies, delinquency, deliciously deviant sexuality and a wonderfully puerile sense of humour. When Andrew Loog Oldham claimed that The Rolling Stones weren’t "a band, they’re more a way of life" he set the tone for The Cramps. Probably more than any other band, The Cramps not only worshipped at the altar of rock & roll, they also happened to live the life with a dedication that verged on the fundamentalist, and it’s in these albums that the die is cast.

Songs The Lord Taught Us, now celebrating its 40th anniversary, was preceded by the Gravest Hits EP the previous year. Comprised of their first two self-released singles, ‘Surfin’ Bird’ and ‘Human Fly’, plus a cover of Ricky Nelson’s ‘Lonesome Town’, the EP’s tracks were recorded and produced by former Box Tops and Big Star frontman Alex Chilton at Ardent Studios in Memphis. For the debut album, the band returned to Memphis and plugged directly into the source, recording at Sam Phillips’ Sun Studio with more reverb, more trash and more, well, more Cramps.

Songs The Lord Taught Us continues to work because of its sincerity. The humour, though often infantile, is played straight and revels in a world of its own making. Take ‘I Was A Teenage Werewolf’. Though laughable at a surface level, the image of a post-pubescent lycanthrope, complete with "braces on my fangs" and suffering "puberty rites and puberty wrongs", complete with a slavering, slobbering performance from Lux that would surely make Lee Strasberg applaud, becomes utterly believable. Or how about the murderous ‘TV Set’ that offers, "I cut your head off and put in my TV set / I use your eyeballs for dials"?

It is technically moronic and rudimentary, and that is one of the album’s main strengths. Unencumbered by musical, Songs The Lord Taught Us suggests that musicians are the people least qualified to make rock & roll and are better off presenting online tutorials about guitar tones and body finishes while taking a coffee break from selling guitar strings. The only scales that matter here are the ones used to weigh out your stash. An accomplished musician would never have dreamt up the brilliantly atonal yet hypereffective fuzz break that colours ‘TV Set’, or the gloriously skuzzy and distorted single chord, complete with string scrapes, that lies at the heart of ‘Garbageman’ before taking flight into a voyage of unhinged chaos. The tutored would have done their very best to minimise or eradicate the feedback, but not The Cramps; and their instinctive embrace of bedlam simply adds to the appeal. This is music that doesn’t stand on convention. It drags convention into a back alley and works it over with switchblades and motorcycle chains, leaving it bloody, bruised and ready to be cleared away with the trash in the morning.

Much has been said about who played what on the album. In later years, Ivy claimed credit for many of the guitar parts deployed throughout, alleging that Bryon Gregory’s extracurricular chemical activities conspired to keep him out of the studio. But, as the line goes, "When the legend becomes fact, print the legend"; I’ll say that Gregory is responsible for the lashings of sustained and fuzzed noise that drones throughout the album. ‘Sunglasses After Dark’ is a case in point. Producing a racket akin to a punch-up in a bee house that’s been lobbed into an echo chamber, the guitar replicates the less benign effects of LSD and creates a more hellish environment for the song’s hoodlum aspirations. Ivy is free to stamp her uncompressed twanging over the top as she liberally dips into Link Wray’s ‘Ace Of Spades’ for inspiration.

It’s worth taking note of Nick Knox’s role at the heart of this psychotic chaos. With no bass guitars at the lower end of the sound spectrum, Knox fills out that space with a greater emphasis on his bass drum and floor toms. This is deceptively simple yet effective stuff that adds to the air of menace while creating a superb trance-like effect. Just check ‘Zombie Dance’ for evidence. Like opener ‘TV Set’, Knox’s work on the floor toms underpins the trashy guitars that slash throughout, fattening the sound before finally letting rip in the chorus and detonating the track.

As well as creating its own murky universe, Songs The Lord Taught Us is a gateway to a world that had largely been forgotten about by 1980, and Lux and Ivy were certainly forward about looking backwards. A cursory glance over the songwriting credits on the album’s red label reveals a number of songwriters beyond the Rorschach/Interior partnership; in those pre-internet days, the curious searched through record racks and crates to find the source of these covers – Jimmy Stewart’s ‘Rock On The Moon’, The Sonics’ ‘Strychnine’, The Johnny Burnette Trio’s ‘Tear It Up’ and Link Wray among others. To meet other people who could point you in the direction was akin to joining the Masons. This writer has very fond memories of finding himself in a dimly lit bar called Le Petite J in Limoges, France in 1986. Run by a pair of long-haired veterans of the Paris 1968 riots, the exposed brickwork walls of the bar were adorned with framed posters of The Stooges, The Velvet Underground and, of course, The Cramps. A conversation was soon struck up and, as talk turned to The Cramps, I was introduced for the very first time to the serrated joys of Link Wray. Not only was this like finding the missing (ahem) link, there was also the realisation that truly raw and primal music existed well before the supposed Year Zero proposed by punk rock. Over the course of several bottles of potent Jenlain beer, the hosts gave me a crash course in rock & roll and psychedelia at its most primitive, and with it the knowledge that things weren’t quite how they’d been or ever would be again. What was important here was catching that original wild, unencumbered and undiluted spirit of rebellion and making sure it remained untarnished by notions of taste, commercialism and nice manners.

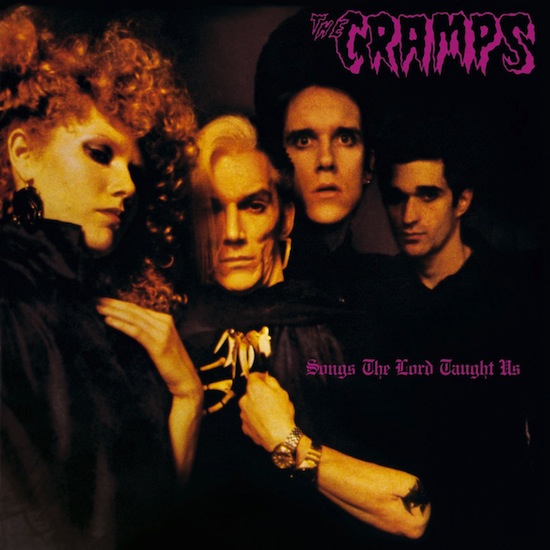

The cover art for Songs The Lord Taught Us tells what we’ll find inside before a note of music is played. Shrouded in darkness, The Cramps look like a gang of twisted hoods ready to corrupt and pervert. To the left Poison Ivy peers down on us, her red hair cascading over her shoulder. Lux, his hair stacked high and his eyes giving a thousand-yard stare, is straight out of a laboratory, as if gasping air for the very first time. Behind him is Nick Knox, ready to start to a knife fight. But it’s the figure of Bryan Gregory that beguiles and haunts. His leathery, pockmarked skin barely stretches over his chiselled cheekbones; his hair, parted to the side with a long, bleached fringe hanging to one side, is a hellish reading of Phil Oakey; on his tattooed left arm he wears not one but two watches. And the eyes – the eyes! – are set in deep sockets, their whites only hinted at, resting beneath arched brows and glowering with psychopathic intent. And if that wasn’t enough, he’s wearing bones for jewellery. And then there’s the logo; fresh from some B-movie horror flick it speaks as loudly as the image it adorns. This, then, is the complete package: sex, horror, illicit thrills and temptation rolled into one irresistible package.

Songs The Lord Taught Us is a great place for the novice to start and for the aficionado to return to. This is where, for good or for ill, psychobilly kicked off – but while The Cramps were frequently imitated, they were never bettered. Their encyclopedic knowledge of first generation rock & roll and the trashier aesthetics that surrounded it was unrivalled and ensured a deep-rooted love that was palpable throughout their music. In some respects, The Cramps represent an alternate version of folk music, a communication of art from the gutter that’s every bit as American as Jackson Pollock or Truman Capote. They became as influential as the avatars they championed and maintained their standards of rebellion. That fiercely independent stance, which increased in reaction to legal wrangles with their record label after the release of second album Psychedelic Jungle, found them shunning the mainstream before storming it on their own terms with a surprise hit single (1989’s ‘Bikini Girls With Machine Guns’), festival headline slots and the occasional TV guest appearance.

But it’s with Songs The Lord Taught Us that their blueprint is established. This is a glorious, hermetically sealed world of dark delights and puerile pursuits. Take the plunge and go down to their lair. You won’t come back the same, but you’ll be all the better for it.